Written by John Lawton

he cluster of familiar white skullcaps stood out conspicuously amid the colorful Chinese costumes on the pier. But the presence of Muslims in the turbulent crowd there to greet us was not as incongruous as it seemed. For we were sailing into Quanzhou after retracing the routes of the Muslim warriors, Muslim missionaries and Muslim merchants of centuries past who had spread the new monotheistic creed of Islam from the Arabian Peninsula as far east as China. So it was fitting at journey's end to be welcomed by some of the descendants of those who had preceded us along Islam's path east.

he cluster of familiar white skullcaps stood out conspicuously amid the colorful Chinese costumes on the pier. But the presence of Muslims in the turbulent crowd there to greet us was not as incongruous as it seemed. For we were sailing into Quanzhou after retracing the routes of the Muslim warriors, Muslim missionaries and Muslim merchants of centuries past who had spread the new monotheistic creed of Islam from the Arabian Peninsula as far east as China. So it was fitting at journey's end to be welcomed by some of the descendants of those who had preceded us along Islam's path east.

Photographer Nik Wheeler and I had journeyed three months to reach Quanzhou, on China's southeast coast opposite the island of Taiwan: from Islam's Arab heartland across Pakistan and India to the islands of the Maldives and Sri Lanka, then via Malaysia to Indonesia and, finally, on to China. We had sailed the Arabian and South China seas in the wake of ancient Arab traders, and had followed the routes of medieval Muslim armies through the Khyber Pass and across the plains of Punjab. Together with earlier Aramco World reporting assignments in the Arab East, the Muslim republics of the Soviet Union, and northwest China - some with Tor Eigeland and other photographers - this totaled some 30,000 kilometers (19,000 miles) traveled along Islam's eastward routes. For although Islam once reached across Spain and into France, before being pushed back at Poitiers in 732, its advances to the west were far outstripped by its advances eastward. And while the Islamic tide ebbed from Spain, the changes it wrought in the East were permanent: Today there are about 500 million Muslims in the broad band of lands running across central and southern Asia from the Red Sea to the Pacific.

Photographer Nik Wheeler and I had journeyed three months to reach Quanzhou, on China's southeast coast opposite the island of Taiwan: from Islam's Arab heartland across Pakistan and India to the islands of the Maldives and Sri Lanka, then via Malaysia to Indonesia and, finally, on to China. We had sailed the Arabian and South China seas in the wake of ancient Arab traders, and had followed the routes of medieval Muslim armies through the Khyber Pass and across the plains of Punjab. Together with earlier Aramco World reporting assignments in the Arab East, the Muslim republics of the Soviet Union, and northwest China - some with Tor Eigeland and other photographers - this totaled some 30,000 kilometers (19,000 miles) traveled along Islam's eastward routes. For although Islam once reached across Spain and into France, before being pushed back at Poitiers in 732, its advances to the west were far outstripped by its advances eastward. And while the Islamic tide ebbed from Spain, the changes it wrought in the East were permanent: Today there are about 500 million Muslims in the broad band of lands running across central and southern Asia from the Red Sea to the Pacific.

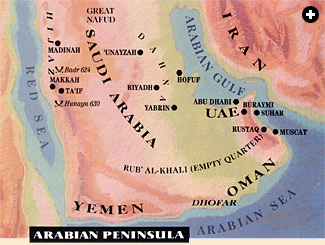

The rise of Islam in the East, as a religion and as a military and political power, was meteoric. Within a decade of establishing an Islamic city-state in Madinah, in today's Saudi Arabia, in the mid-620's, the Prophet Muhammad had welded together the divided pagan tribes of Arabia through thejini-fying force of the monotheistic religion revealed to him. And within a further decade his successors, the caliphs Abu Bakr (632-634) and 'Umar ibn al-Khattab (634-644), had overthrown the Persian Sasanid Empire in Iraq and Iran and expelled the Byzantines from Palestine, Jordan and Syria, effectively pushing aside the two superpowers of the era. Later, the Umayyad (661-750) and Abbasid (750-1258) hereditary caliphs incorporated Sind, Afghanistan and Central Asia into the Islamic realm, while other Muslim conquerors spread Islam to India.

|

| This modern mirror-image calligraphy reads, “In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful” - the phrase that begins every chapter of the Qur’an but one, and every endeavour of a pious Muslim. |

|

| Quba, the first mosque of Islam, was originally built by the Prophet Muhammad and his fellow emigrants from Makkah on their arrival in Madinah in 622. That year marks the beginning of both the Muslim era and the Muslim calendar. |

Further east, Islam was propagated by pious Muslim merchants who settled in Sri Lanka, the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia to trade in spices, porcelain and silk. Some even settled as far east as China, and it was members of China's Hui minority - descendants of either Chinese converts to Islam or Chinese intermarriages with Muslim merchants - who welcomed us to Quanzhou.

Ended inclemently by sea - you could not see the bow of the ship from the bridge for fog as we entered Chinese waters - our journey east began by land in the hot, clear deserts of Saudi Arabia, at the gates of Madinah, the adopted home of the Prophet and the first capital of Islam. As a non-Muslim, I could not enter Islam's second-holiest city, where Muhammad lies buried in the Prophet's Mosque with the caliphs Abu Bakr and 'Umar. But a room in a high-rise hotel in the modern suburbs of the city - where, at Quba, stands the very first mosque built in Islam - provided a panoramic view of the city's slender minarets and lofty domes. Even from a distance, Madinah lived up to the epithet al-Munawwarah - the radiant - that is usually added to its name: The night before our departure, bright lights illuminated the city's shrines in dazzling white against the background of the black volcanic hills amid which Madinah stands.

At the time of Muhammad's revelations - later all collected in the Qur'an - Madinah was an oasis famed for the dates from its palm groves and notorious for the feuding among the several fissile Arab clans that cultivated them. About 618, after nearly a century of feuding, a great battle broke out involving almost all the clans of the oasis; it resulted in heavy casualties and ended inconclusively.

The clans of Madinah, having heard of Muhammad's inspired religious leadership, sent envoys to the commercial city of Makkah, 330 kilometers (210 miles) south, asking the Prophet to mediate their disputes and, eventually, to settle in their oasis. Faced with increasing opposition in his native Makkah, where the city's powerful merchant families saw his message - submission to the will of the One God - as a threat to their positions as aristocrats of the Arabian Peninsula and to their own local pagan cults, Muhammad accepted the clans' invitation and moved to Madinah, preceded by a small group of persecuted and dispossessed adherents to the new faith.

This emigration is known as the hijrah and marks the beginning of the Muslim era; Islamic chronology commences with the first day of the lunar year in which the emigration took place: July 16,622, in the Gregorian calendar of the West.

In Madinah, Muhammad won more converts. But continuing friction with the Makkans culminated, in March of 624, in Islam's first military confrontation, called the Battle of Badr after what is now a small town southwest of Madinah. Though outnumbered three to one, the 300 Muslims trounced the Makkans in this crucial encounter, killing some 70 of the enemy and capturing about an equal number.

Some Western historians say the victory was a result of the discipline displayed by Muhammad's army, which fought in ranks instead of using traditional hit-and-run tactics, while others suggest that the farmers of Madinah were physically stronger than the townsmen of Makkah. But according to The Cambridge History of Islam, "the chief reason for the victory was doubtless the greater confidence of the Muslims as a result of their religious faith."

A year later the Makkans struck back. Assembling an army of some 3000 men, including 200 cavalry, they met the Muslims at Uhud, a volcanic ridge outside Madinah. Once again, the Prophet's army, with only 700 men and no cavalry, was heavily outnumbered. Nevertheless, the superior Muslim infantry was close to victory when a flank attack by the Makkan cavalry forced them to retreat. The Makkans, however, believing the battle won and Muhammad dead - he was in fact only wounded - failed to press home their advantage, and withdrew. And although the Muslims were badly mauled at Uhud - 75 were slain - the Makkans failed in their strategic aim of destroying Muhammad.

|

| The interior of the Prophet's Mosque at Madinah with its qiblah, or prayer niche, which indicates the direction of Makkah. |

|

| The Ka'bah, spiritual center of the Islamic world, toward which Muslims turn to pray five times a day, is an ancient stone structure about 17 meters (55 feet) high, roughly cubical in shape. It is customarily washed each year by Saudi Arabia's king. The kiswah that covers the Ka'bah, and a black cloth on which Qur'anic verses are embroidered in gold, is replaced every year. |

In 627, the Makkans, in alliance with several Bedouin tribes, again attacked Madinah - this time with a force said to comprise 7000 to 10,000 men, including 600 cavalry. To counter the threat of the cavalry, the Muslims, who had only 3000 men and no more than a score of horse, dug a deep trench across the northern side of the oasis - whose other sides were protected by ancient lava flows - to force the Makkans into what was, in effect, a siege. This was outside the normal patterns of Arab warfare, and the attackers, and their Jewish allies within Madinah itself, soon became restive. Dissension among them grew, and when the weather became exceptionally cold and a violent wind unleashed torrents of rain, the vast alliance faded away.

The collapse of the siege was a great victory for the Prophet: The Makkans, despite having committed all their resources to the effort, had again failed to destroy him. Muhammad further strengthened his position by a series of alliances with the Bedouin tribes of the Hijaz, the Red Sea coastal region of Arabia in which Makkah and Madinah are located. At the same time, he won the allegiance of several leading Makkans previously bitterly opposed to him, among them the astute politician 'Amr ibn al-'As and the gifted general Khalid ibn al-Walid, whose cavalry had wrought such havoc on Muhammad's flank at Uhud.

Now, with their help, the Prophet was able to re-enter Makkah and, in effect, conquer the city virtually unopposed. On January 11,630, he returned to his native town in triumph at the head of 10,000 troops who entered the city in four columns, only one of which met with resistance. Muhammad destroyed the idols in the Ka'ba, a focus of pilgrimage since ancient times, and put an end to pagan practices there forever.

Muhammad's treatment of the Makkans was generous, establishing an ideal for future conquests. Addressing the enemy he had just defeated, and at whose hands he had suffered intense persecution, the Prophet asked, "Men of Quraysh, what do you think I am about to do with you?" "Everything good," they answered, "for you are a noble and generous brother, son of a noble and generous brother." The Prophet said, "Rise and go, for you are free." Thus it is not surprising that when a new threat arose - the massing of hostile Bedouin tribes at Hunayn, near Ta'if - some 2000 Makkans marched out with the Muslims to defeat them, making the Prophet the undisputed temporal and religious leacier of the Hijaz.

Muhammad at once sent 'Amr to what is today Oman, the second-largest country on the Arabian Peninsula, to invite its Arab rulers to embrace Islam, thus making the port of Suhar Islam's gateway to the Arabian Sea and the starting point of its maritime path east.

It was in 'Amr's footsteps that we began our journey.

I could find no record that precisely described 'Amr's journey from Madinah to Oman, so Saudi Aramco photographer Abdullah Dobais and I took the route which, in 'Amr's time, would have been the most likely: the ancient caravan trail from the mountainous Hijaz across the central plateau of Arabia and the fertile al-Yamamah region to Yabrin, once the most important staging post for caravans across the Rub' al-Khali to Oman. Although this 1200-kilometer (750-mile) journey would have taken 'Amr many weeks by camel, it took us only three days by car, mostly on modern asphalt highways.

Starting from the small plain called Manakhah where caravans to Madinah once camped — the name derives from nikh, the Arabic command to make a camel kneel - we headed east across gravel plains, their monotony broken only occasionally by weirdly weathered rock outcrops and flat-topped acacia trees.

We stopped at the small oases of al-Hanakiyyah, Nuqran and 'Uqlat al-Suqur - now consisting mostly of dilapidated adobe homes and neglected palm groves, abandoned years ago in favor of modern buildings and businesses built beside the nearby highway.

Between al-Hanakiyyah and Nuqran we crossed the path of the Darb Zubaydah, the pilgrims' road built by Zubaydah, wife of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, in about 740. It connected the holy cities of the Hijaz with southern Iraq via a string of about 50 way stations, which in addition to accommodation for pilgrims, caravan crews and their animals included wells that supplied water for drinking and bathing. Although little now remains of the highway or its facilities, the circular, basalt-built pool at Khurabah - six meters (20 feet) deep, 40 meters (130 feet) in diameter and with 21 steps down into it - has been partially rebuilt.

Continuing across the stony desert, we skirted escarpments which, although not very high, seemed to us like major elevations compared to the featureless adjacent plain. And we crossed fingers of sand reaching out from the Great Nafud desert to our north before finally arriving at the bustling market town of 'Unayzah, on the eastern rim of Arabia's central plateau.

Here too we found the old part of town abandoned in favor of the new and modern, some mud brick walls already collapsing to reveal gaping cross sections of empty homes.

|

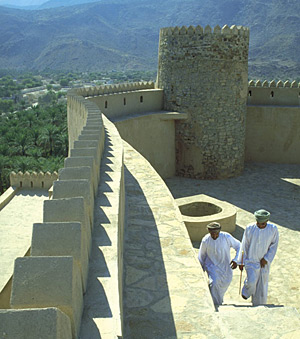

| Young Omanis relax in the cool shade of the recently restored Restaq Fort. |

|

| The remains of Jawatha Mosque, built about 635 and reputedly the oldest mosque in eastern Arabia, are still a cherished site for prayer. |

Something similar must have happened to the historically documented but long disappeared "30 palaces and 30 gardens" of Hajr, once the main town of the al-Yamamah region, which was then, as now, the heartland of Arabia. Unable to locate it, we headed for the present center of the region and the country, with its palaces and parks: the modern Saudi capital of Riyadh.

Here we joined what maps call the "Old Yamamah-Baghdad Route" running roughly north-south across Arabia. Fighting against early-morning rush-hour traffic, we left Riyadh's futuristic city center, passed suburban industrial complexes and outlying mechanized farms, and finally emerged among the orange dunes of the Dahna - the great arc of sand sweeping southward from the Great Nafud to the Rub'al-Khali.

On the edge of the Rub' al-Khali, or Empty Quarter, a desert larger than France, or Colorado and New Mexico combined, lies the oasis of Yabrin, once a busy crossroads for the camel caravans that were the livelihood of ancient Arabia and along which the news of Islam flowed 14 centuries ago. From here, two caravan trails led out across the Rub' al-Khali: one - the continuation of the Old Yamamah-Baghdad Route - headed south to the incense-growing region of Dhofar, and the other east to Oman.

Modern traffic, however, gives Yabrin and the roadless Empty Quarter a wide berth, following instead the Arabian Gulf coastal highway from Hofuf through the United Arab Emirates to Oman. As a result, Yabrin today is an isolated backwater, 95 kilometers (56 miles) from an asphalt road along a rutted track; its fort, that once stood sentinel over lucrative trade routes, is a ruin.

We doubled back to Hofuf, the center of Saudi Arabia's largest oasis, al-Hasa, and the site of what is reputedly the oldest mosque in eastern Arabia. Built about 635 by the Bani 'Abd al-Qays tribe at Jawatha, following a visit to Madinah during which their leaders embraced Islam, the original mosque has long since vanished. But several stone arches of undetermined age still stand on the pleasantly-landscaped site - cherished by Muslims, and still used for prayer.

From Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, the highway to Oman cuts inland, via the oasis of Buraymi, to the mountainous interior of Oman - 'Amr's final destination. For although the Sasanid Persians controlled the coast, they allowed the Arab Azd tribe, from whom the present ruling family of Oman is descended, to exercise considerable autonomy in the interior of the country. In return for controlling the inhabitants of the mountains, they were allowed to collect taxes, and the head of the tribe was given the Sasanid administrative title julanda.

When 'Amr arrived in Oman with a letter from Muhammad to Julanda Bin-Mustansir, enjoining him and his subjects to embrace Islam, he found that the head of the Azd was dying. His mission, however, was successful: The julanda's two sons accepted Islam and sent a letter to the pagan Sasanid governor of Rustaq, inviting him to do the same. When he refused, they defeated him in battle. The Azd then besieged the Persian garrison at Suhar, forcing it to surrender and forcing the Persians to leave the country.

|

| Recently restored Restaq Fort has played key roles in Oman's history: Originally the seat of the pre-Islamic Persian governors, it also served several times as the Muslim sultanate's capital. |

Recently restored to their original splendor, the honey-colored fort at Rustaq Oasis and the dazzling-white coastal garrison at Suhar today serve as magnificent reminders of Oman's important role in the spread of Islam - both by land and by sea. From Suhar, legendary home of Sindbad the Sailor and, according to 10th-century geographer al-Istakhri, "the greatest seaport of Islam," Arab sailor-merchants carried word of their new religion as far east as China, while the Azd, under their great general al-Muhallab ibn Abi Safra, took part in the conquest of Khurasan.

Meanwhile, the Prophet Muhammad had sent his son-in-law, 'Ali ibn Abi Talib, south to teach the new principles of Islam to the tribes of Yemen - then, as now, the most populous corner of the Arabian Peninsula. A Persian satrapy where Judaism and Christianity were upheld by warring factions against an anarchic background of tribal paganism, Yemen did not seem to be a fertile field for the Muslim message. But surprisingly, conversion was spontaneous: All 14,000 members of the powerful Hamdan tribe are said to have embraced Islam in a single day.

With his authority supreme elsewhere in Arabia, Muhammad now turned his attention to the still-pagan north of the Arabian Peninsula. In October, 630, the Prophet led the greatest of all his expeditions - reportedly comprising 30,000 men and 10,000 horse - against the oasis of Tabuk. Here, without a single military engagement, he concluded treaties with the region's tribes which resulted in the capitulation of all of northwestern Arabia and the establishment of Islam throughout the Peninsula.

This event not only opened the way for Islam's thrust into the Fertile Crescent and beyond, but was also significant for another reason. The treaties signed with the Jewish and Christian populations of Maqna and Aylah, on the Gulf of Aqaba, set the pattern for the later establishment of the dhimmi system in the Islamic polity. Dhimmis, or protected peoples, were granted security and the rights to retain their property and profess their religion, on condition that they paid an annual tax. In practice, not even pagans, whose concepts stood in stark conflict with the uncompromisingly monotheistic principles of Islam, were forced to convert.

Thus, when Muhammad died less than two years later in Madinah, the stage was set for the expansion of both the Islamic religion and Arab rule outside the limits of "the island of the Arabs," as the Arabian Peninsula was known.

|

| The tile-sheathed shrine of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem - begun in 684 and restored by Sulëyman the Magnificent - is built over the rock from which Muhammad is believed to have ascended on his nocturnal journey to heaven. It is the earliest great Muslim building in existence. |

In the great expansive thrust that followed, unsurpassed if not unparalleled in world history, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the forces released by the new religion and the warlike energies of the Arab conquerors.

In A History of the Arab Peoples, Albert Hourani explains that "the Arabs who invaded the [Byzantine and Sasanian] empires were not a tribal horde but an organized force The use of camel transport gave them an advantage in campaigns fought over wide areas; the prospect of land and wealth created a coalition of interests among them; and the fervour of conviction gave some of them a different kind of strength."

Most Muslim historians, on the other hand, emphasize the primacy of the ideological motive for the expansion of Islam. They point out that the martial tactics and strengths of the Arabs after their conversion to Islam were not significantly different from those they possessed in pre-Islamic times. But once they had become Muslims, their new convictions led to a unification of purpose and a sense of mission, and thus to success in both the religious and military spheres.

However it was motivated, the Muslim advance was facilitated by the fact that the two major powers of the Near East, the Byzantines and the Persian Sasanians, were exhausted by years of constant conflict with each other. They also faced rising resentment among their subject peoples in the Fertile Crescent bordering Arabia - the Holy Land, Greater Syria and Iraq. And many of these peoples were Arabs who, because of their ties of language and customs, not only welcomed the Peninsular Arabs but strengthened their forces with contingents of their own.

"Nevertheless," says The Cambridge History of Islam, "despite these concomitant circumstances, the decisive factor in this [Arab] success was Islam, which was the co-ordinating element behind the efforts of the bedouin, and instilled into the hearts of the warriors the belief that a war against the followers of another faith was a holy war...."

Muslim and Byzantine armies first crossed swords in 632 at Mu'tah, in [Jordan, when Zayd libn Harithah, one of Muhammad's closest companions, led 3000 men out of Arabia to avenge the death of a Muslim envoy executed by the Ghassanids, Christian Arabs who were clients of the Byzantines. The battle ended disastrously for the Muslims: Zayd and two other leaders who subsequently took command were all slain, leaving the newly converted Khalid ibn al-Walid to lead the shattered remnants of the Muslim army back home.

|

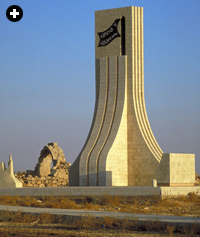

| A modern memorial and an ancient mosque mark the site of the battle of Mu'tah in Jordan, where Muslim and Byzantine armies clashed for the first time in 632. |

Today, an impressive modern monument stands on the traditional site of the battle, approximately opposite the Jordanian Military Academy of Mu'tah and beside the remains of an ancient mosque, of which only one arch and the prayer niche are still standing. In the nearby town of Mazar, another impressive modern memorial to the Muslim dead of Mu'tah - four towering stone stelai, each penetrated by a tall, slender arch - stands opposite a twin-minaretted mosque. And in a nearby park is the small, green-domed mausoleum of Zayd.

To reach Mu'tah I had traveled, with Aramco World's Amman-based photographer Bill Lyons, along one of the most historic and scenic roads in the Middle East: The King's Highway linking Aqaba, on the Red Sea, with Amman, the original Philadelphia of 2000 years ago and now the capital of Jordan.

Along this route, in use since 3000 BC, are Petra, rock-carved capital of the Nabatean Arabs; commanding Crusader castles at Karak and Shobak; and a litany of Biblical sites, including Machaerus - present-day Mukawir - where Salome danced and John the Baptist lost his head. Even parts of the road paved by the Romans are still visible in places.

The route is at its most spectacular when it plunges through the gorges of Wadi al-Hasa and Wadi Mujib; the latter, about 3000 meters (almost two miles) wide and 1440 meters (4600 feet) deep, is comparable to the United States'Grand Canyon.

We started our journey along the King's Highway at dawn at Petra, walking through the Shiqq, the winding fissure between overhanging cliffs which suddenly opens out into a hidden valley lined with temples, "treasure houses" and tombs carved into the salmon-pink rock by the Nabateans some 2300 years ago.

By mid-morning, we were clambering over the battered battlements of Shobak fortress, built on a mountain of rock by the Crusader Baldwin I, King of Jerusalem, in about 1115 and captured, in 1189, by Salah al-Din, or Saladin. In mid-afternoon we paused for Turkish coffee beneath the glowering walls of Karak Castle, the most important Crusader stronghold in Jordan. And as the sun set we climbed slowly out of Wadi Mujib and headed across rolling highlands to modern Amman.

We had traversed 5000 years of history in the course of a single day.

The next stage of our journey took us from the Jordanian highlands to below sea level, along the 100-kilometer-long (62-mile) Jordan Valley, which lies 200 to 400 meters (656 to 1312 feet) below sea level. Following the Jordan River from the Dead Sea to Lake Tiberias, we turned east along its northernmost tributary, the Yarmuk, present-day frontier between Jordan and Syria.

It was here that the Muslims and Byzantines fought their most crucial battle.

Following Muhammad's death, his successor Abu Bakr launched simultaneous offensives against the Byzantines and the Persians.

Khalid ibn al-Walid, "the Unsheathed Sword of God," led a column of Muslims against the Persians, attacking the capital of southern Iraq, Hirah, which only saved itself from armed occupation by peaceful submission to the Muslim armies and the payment of a tax.

Meanwhile, two columns of Muslims entered Jordan, and another, led by 'Amr ibn al-'As, penetrated southern Palestine. Sergius, the patrician of Palestine, was defeated and his country overrun; only a handful of cities, such as Jerusalem, held out in expectation of reinforcement from the Byzantine emperor Heraclius.

Hearing that Heraclius was equipping a large army, Abu Bakr ordered Khalid to hasten from Iraq to Syria. Khalid led a forced march by a few hundred men across the Syrian desert, appeared almost miraculously to inspire the Muslim troops with fresh courage and, in a series of battles, defeated Heraclius and occupied Damascus in September of 635.

Meanwhile, in Persia, the energetic Shah Yaz-degerd III had ascended the throne and raised a large army. 'Umar, who had succeeded Abu Bakr as caliph, sent reinforcements, but the Muslims suffered a severe defeat in 634 known as the Battle of the Bridge - where al-Muthana, valorous chieftain of the Bakr bin Wa'il tribe of northern Arabia, saved the army from annihilation by putting up a heroic stand at a bridge over the Euphrates.

The victory of Buwayb, in 635, restored the Muslims' fortunes, however, and at a decisive battle at Qadisiyyah, in 636, they definitively defeated the Persians and gained complete control of Iraq.

Meanwhile, Heraclius, refusing to admit defeat, had raised a new army and marched south to meet the Muslims in the Yarmuk Valley. This was the scene of a pitched battle in August, 636, when a dust storm - a more severe handicap to the Byzantines than to their desert-bred opponents -helped the Muslims win a critical victory.

With relief now impossible, Jerusalem sued for peace. 'Umar personally S concluded a treaty with the f city notables on very generous terms: Christians were given protection and freedom of worship on payment of a tax, which was in fact less heavy than the one levied by the Byzantines in the past.

According to Arab historians who describe the event, 'Umar amazed the people of Jerusalem, accustomed as they were to Byzantine splendor, by entering the city that his forces had conquered clad not in magnificent robes but in a coarse mantle. He cleansed and then prayed on a site in the southeastern part of the present Old City that he found abandoned and littered with rubble. This site is thought by some to be the former location of the Herodian Temple that was destroyed by the Romans in AD 70. A mosque was built at or near the spot where 'Umar prayed -a modest edifice not to be confused with the magnificent building which stands there today: the Dome of the Rock, Qubbat al-Sakhrah, which stands over the naked rock from which the Prophet made his celebrated nocturnal ascent (mi'raj) to heaven. Today's building, sheathed in multi-patterned tiles and capped with a gold-leaf dome, was not begun until 684 and was restored by the Ottomans in the 1560's -but it is still the earliest great Muslim building in existence, and it stands in the city which, even in the Prophet's lifetime, Muslims considered to be the third holiest in the world, after Makkah and Madinah.

Besides the surrender of Jerusalem, the Muslim victory at Yarmuk also delivered most of Syria into Muslim hands. But attacks northwestward in 673 and 717against the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, in modern Turkey, were unsuccessful, enabling the heartlands of the Byzantine Empire to continue in existence until 1453.

The eastward thrust of Islam, however, continued unabated.

After occupying Iraq, the Muslims pursued the Persians across the Iranian plateau and, in 642, in the neighborhood of Nihavand, won what they thereafter called "The Victory of Victories," one which sealed the fate of the Sasanian Empire and established Muslim rule over the Middle East.

Unable to offer any serious resistance after Nihavand, Shah Yazdegerd retreated first to Isfahan and then to Istakhr, the ancient Persepolis, finally taking refuge in Merv, some 230 kilometers (140 miles) southwest of the Oxus River, -in the present-day Republic of Turkmenia. Here, in 651, he was assassinated by a local satrap: The Sasanian dynasty was at an end and the Muslims' way to Central Asia lay open.

It was another 60 years, however, before the Muslims turned their attention to the territory across the Oxus, which they called "What Lies Beyond the River."

For the conquests begun under Abu Bakr and continued under 'Umar had increased the Islamic empire enormously in extent - and in administrative complexity. 'Umar allowed local officials in occupied lands to carry on and confined himself to appointing a commander or governor with full powers, responsible directly to Madinah, thus giving the new Muslim polity a certain unity.

But Arab logistics were stretched and conflicts within the Muslim leadership over the question of succession brought the first phase of Islam's advance eastward to a close.

|

Aramco World contributing editor John Lawton has eight other complete issues of the magazine to his credit, the first published in 1977. He is also the author of Samarkand and Mukhara, published in London by Tauris Parke Books. |