t was around two o’clock on a mild mid-February afternoon that colleagues called head archeologist Yousef Madjidzadeh to look at some telltale markings in a dusty trench. It was the last day of the six-week digging season at the Jiroft archeological site in the southeast Iranian desert, and Madjidzadeh (mad-zhid-zah-day) was jotting down notes before closing up for the year. The Iranian-born archeologist, who has been excavating at Jiroft for two years, has become increasingly convinced that the remains of this 4500-year-old city hold the key to a Bronze Age kingdom whose existence promises to rewrite at least a chapter or two of the history of the ancient Middle East.

t was around two o’clock on a mild mid-February afternoon that colleagues called head archeologist Yousef Madjidzadeh to look at some telltale markings in a dusty trench. It was the last day of the six-week digging season at the Jiroft archeological site in the southeast Iranian desert, and Madjidzadeh (mad-zhid-zah-day) was jotting down notes before closing up for the year. The Iranian-born archeologist, who has been excavating at Jiroft for two years, has become increasingly convinced that the remains of this 4500-year-old city hold the key to a Bronze Age kingdom whose existence promises to rewrite at least a chapter or two of the history of the ancient Middle East.

“I took the pick in my hand and started to help dig out what turned out to be a remarkably well-preserved stamp-seal impression,” Madjidzadeh recalls, now back at his home in the Mediterranean port city of Nice, France.

Painstakingly extracting the five-centimeter- (2"-) long rectangle from the trench wall’s packed clay, the archeologist turned it to the sunlight. Amid faintly inscribed lines and images of human and animal figures, he was amazed to discover what appeared to be an unfamiliar form of writing. To Madjidzadeh, the seal impression came as his first evidence that this ancient city’s society was literate.

“To be able to say that Jiroft was a historic civilization, not a prehistoric one, is a great advance,” he says. “Finding writing on that seal impression brought tears to my eyes. Never mind that we can’t read it—that’ll come later.”

Though others have downplayed Madjidzadeh’s declarations that Jiroft was more than a regional culture, archeologists generally agree, he says, that a distinct civilization is characterized by unique monumental architecture and by its own form of writing. “This past winter, we found both,” he beams.

Gray-bearded, easy-going and energetic in his mid-60’s, Madjidzadeh is feeling the glow of vindication. A few years after Iran’s 1979 revolution, he was dismissed as chairman of the department of archeology at Tehran University. After years of self-imposed exile in Nice with his French-born wife, he returned during the intellectual thaw that followed the 1997 election of President Mohammad Khatami.

The discovery of the Jiroft site came by accident. In 2000, flash floods along the Halil River swept the topsoil off thousands of previously unknown tombs. Seyyed Mohammad Beheshti, deputy head of Iran’s Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization (ICHTO), asked Madjidzadeh to begin excavations because of the archeologist’s long-standing bullishness on Jiroft’s significance.

|

|

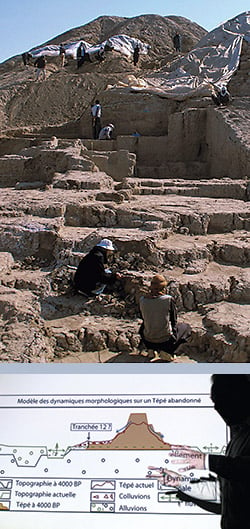

| Excavations at Jiroft’s Konar Sandal A, one of the site’s two major mounds, are revealing the base of what may have been one of the world’s largest ziggurats. (Mohammad Eslami-Rad / Gamma) |

As the author of a three-volume history of Mesopotamia and a leading Iranian authority on the third millennium BC, Madjidzadeh has long hypothesized that Jiroft is the legendary land of Aratta, a “lost” Bronze Age kingdom of renown. It’s a quest that he began as a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago, when in 1976 he published an article proposing that Aratta, which reputedly exported its magnificent crafts to Mesopotamia, was located somewhere in southeastern Iran.

According to texts dating from around 2100 BC, Aratta was a gaily decorated capital with a citadel whose battlements were fashioned of green lapis lazuli and its lofty towers of bright red brick. Aratta’s artistic production was so highly regarded that about 2500 BC the Sumerian king Enmerkar sent a message to the ruler of Aratta requesting that artisans and architects be dispatched to his capital, Uruk, to build a temple to honor Inanna, the goddess of fertility and war. Enmerkar addressed his letter to Inanna: “Oh sister mine, make Aratta, for Uruk’s sake, skillfully work gold and silver for me! (Make them cut for me) translucent lapis lazuli in blocks, (Make them prepare for me) electrum and translucent lapis!” prayed the Sumerian ruler.

“When one imagines that Uruk was the heart of the Sumerian civilization and that its king is asking another ruler about 2000 kilometers (1200 mi) distant to send his artisans, one realizes that the quality of their work must have been extraordinary,” says Madjidzadeh. “The craftsmen must have been known all over. Today there is no doubt in my mind that Jiroft was Aratta.” A handful of colleagues agrees, including the French epigrapher François Vallat, who compares Jiroft to the Elamite kingdom of southwestern Iran.

So far, however, there is no proof, and others are less sure.

“When you start reconstructing actual geographical regions based on legend and mythology, you’re always in deep water,” says Abbas Alizadeh, an Iranian-born archeologist at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. “Some scholars think Aratta is in Azerbaijan. Others say Baluchistan or the Persian Gulf. It’s a murky business.”

Yet even if Jiroft turns out not to be Aratta, it is nevertheless a pivotal clue to a better understanding of the era when writing first flourished and traders carried spices and grain, gold, lapis lazuli and ideas from the Nile to the Indus. Although not on a par with the more influential civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Indus Valley, “Jiroft is obviously a very important archeological complex,” says Holly Pittman, an art historian at the University of Pennsylvania who is one of a growing number of non-Iranian scholars who are being allowed into the country. “It’s an independent, autochthonous Bronze Age civilization with huge numbers of settlements of all different sizes that we have only just begun to explore.” By comparison to the research documenting other third-millennium civilizations, these are indeed very early days, she explains. “We don’t yet have enough material to compare it to Mesopotamia. But you have to remember that 500 teams of archeologists have been digging in Mesopotamia for 100 years. In Jiroft, we’ve had two seasons with one team of fewer than 30 scientists.”

|

|

| “The artists had such a naturalistic way of rendering images,” says Yousef Madjidzadeh, foreground. “It was a style that was not seen anywhere else in that era.” (Mohammad Eslami-Rad / Gamma) |

Even so, among the spectacular finds so far are the remains of a city a kilometer and a half (.92 mi) in diameter, an unusual two-story citadel surrounded by a fortress wall 10.5 meters (34') thick, and a ziggurat resembling Sumerian ones that is among the largest in the ancient world—17 meters (54') high and 400 meters (1280') on each side at the base. The team has also uncovered 25 stamp and cylinder seal impressions from two to five centimeters (7/8"–2") long that depict bulls, ibex, lions, snakes, human figures—and writing.

Perhaps the most impressive discoveries have been staggering numbers of carved and decorated vases, cups, goblets and boxes made of a soft, fine-grained, durable gray-greenish stone called chlorite. Literally tens of thousands of pieces have been found, but the vast majority have been looted from their original tombs by local farmers, who were the first to stumble across the gargantuan honeycomb of gravesites uncovered by the floodwaters of 2000.

“Thousands of people were digging,” Madjidzadeh explains, and antiquities dealers swooped in behind them to buy up the finds by the dozens. Farmers often sold chlorite vases worth tens of thousands of dollars on the international market for a few sacks of flour. Ultimately, in the fall of 2002, the Iranian authorities stepped in to halt the looting and seize hundreds of contraband artifacts.

|

|

|

Major archeological sites from the fourth and third millennia BC.

Chlorite vessels similar to the stunning examples recently unearthed at Jiroft in southeastern Iran have been found from the Euphrates to the Indus, as far north as the Amu Darya and as far south as Tarut Island, on the Gulf coast of Saudi Arabia. Iranian-born archeologist Yousef Madjidzadeh speculates that some of these objects were in fact imported from Jiroft, which he is convinced is the legendary third-millennium-BC city of Aratta. Other archeologists, however, dispute this conclusion, maintaining that the vases, bowls and cups from Mesopotamian and Indus Valley sites were manufactured locally. What is clear is that Jiroft traders brought lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and carnelian from the Indus to decorate the ornate vessels they manufactured.

|

The Jiroft artifacts are a “missing link” in understanding the Bronze Age, Madjidzadeh says, because they help explain why so many incised chlorite vessels, all with remarkably similar imagery, have turned up at widely separated ancient sites, from Mari in Syria to Nippur and Ur in Mesopotamia, Soch in Uzbekistan and the Saudi Arabian island of Tarut, north of Bahrain. Until now, the principal center of production of these vessels was a mystery. Although some of them were probably manufactured locally, the sheer volume of artifacts at Jiroft argues that the most prolific chlorite workshops of all were there. (See sidebar, page 8.)

Jiroft artisans fashioned pieces with what seems strange and enigmatic iconography. Some were encrusted with lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, carnelian from the Indus Valley, turquoise, agate and other semiprecious, imported stones. “The artists had such a naturalistic way of rendering images,” says Madjidzadeh. “It is a style that was not seen anywhere else in that era.

“There must certainly have been a school of stonecarvers, because you see such an aesthetic unity of these objects throughout the kingdom. This high-level artistic quality did not suddenly appear from nowhere,” he maintains. “The traditions must have taken 300 to 400 years to develop.”

Carved into one gray chlorite cup, mythic creatures with human heads and torsos and bulls’ legs hold panthers upside-down by their tails. On the surface of a stone weight shaped roughly like a ladies’ handbag, two horned scorpion-men appear to swim toward each other. “Hunters who were believed to be as powerful as bulls or as agile as lions entered into legend, and their images became animalized as bull-men and lion-men,” the archeologist suggests in explanation.

Round chlorite boxes are decorated with representations of curved gates, woven reed walls, ziggurats and other architectural details that hint at what Jiroft’s buried buildings probably looked like.

|

|

|

rom the middle to the late third millennium BC, vases, bowls and cups made of chlorite were traded throughout the area shown on the map above. Similar to steatite and soapstone, the mineral was valued by artisans because it was durable but soft enough to carve easily and fine-grained enough to hold carved details well. Its color ranged from jade green (from which came its Greek-derived name) to smoky gray, with some pieces nearly as black as obsidian. rom the middle to the late third millennium BC, vases, bowls and cups made of chlorite were traded throughout the area shown on the map above. Similar to steatite and soapstone, the mineral was valued by artisans because it was durable but soft enough to carve easily and fine-grained enough to hold carved details well. Its color ranged from jade green (from which came its Greek-derived name) to smoky gray, with some pieces nearly as black as obsidian.

Although abundant chlorite deposits are scattered across Iran and the Hajar Mountains of the United Arab Emirates, archeologists have so far uncovered ancient chlorite quarries and workshops in only two locations: at Tepe Yahya in the Kerman province of southeastern Iran and at Tarut, where some 600 intact vessels and fragments were unearthed. It is still unclear where the raw material for the chlorite objects found in Sumeria originated, and similarly, the chlorite mines at Jiroft remain elusive.

|

Along with the chlorite objects are also pink and orange alabaster jars, white marble vases, copper figurines, beakers and a striking copper basin with a eagle seated in its center, as well as realistic carved stone impressions of heraldic eagles, scorpions and scorpion-women.

Many of the scenes on the Jiroft vessels bear a strong resemblance to the gods, beasts and plants portrayed on Sumerian statues, plaques and cylinder seals. “Jiroft leads me to imagine that Iran had a far greater influence on Mesopotamian culture than I previously thought,” observes Jean Perrot, the grand old man of Middle Eastern archeology in France.

To Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky of Harvard University, who excavated a site named Tepe Yahya some 90 kilometers (50 mi) from Jiroft in the 1970’s, what is particularly remarkable about the Jiroft finds is that so many thousands of brand-new, empty chlorite vessels were manufactured for no other apparent purpose than to be buried in tombs to honor the dead. “The fact that not a single one of them contains even a trace of oils, perfumes, foodstuffs or drugs, nor shows any other sign of use, is very curious,” he marvels.

Despite the crackdown on pillaging and the hiring of a dozen armed guards, theft at Jiroft still continues. This winter, while working on the city mounds, Madjidzadeh received a tip that looters were digging at gravesites six kilometers (3.7 mi) away. Racing to the cemetery with one of the guards, he caught sight of several dozen looters, who escaped on foot when they saw Madjidzadeh coming. One of his laborers later told him that it was rumored the looters had managed to spirit away a priceless golden fish figure. One looted gravesite reportedly yielded an astonishing 200 artifacts, including 30 finely crafted chlorite vessels.

“Was it the tomb of the lord of Aratta?” asks Madjidzadeh sadly. “Because all the objects were ripped out of context and have disappeared, we’ll never know—even if they turn up in the antiquities market.”

On his days off, the archeologist travels to surrounding villages to give lectures about the significance of Jiroft and its irreplaceable artifacts.

“I show photos of the objects and our excavations and tell the villagers in simple language that all these works belonged to your grandparents, your ancestors,” he explains. “‘They are your heritage. You don’t sell your heritage. If we put these cups and vases in a museum, they will attract tourists. This will bring more money than selling the pieces once or twice. You and your children will benefit from the tourists and education.’ Little by little, people understand more about the cultural value of the finds.”

On the international art market, it’s a different story. Museums and private collectors have been quick to recognize the cultural, esthetic and, in particular, monetary worth of artifacts that Madjidzadeh is sure were stolen from Jiroft.

“I scour the Internet, auction catalogues and brochures and have been shocked to see museums in Switzerland, Japan, Turkey, Pakistan and elsewhere buying these objects,” he says.

|

|

| Top: An Iranian archeologist and local workers dig on the west side of Jiroft’s second mound, Konar Sandal B. Above: A slide of the cross section of a third-millennium-BC tell—a mound created by centuries of habitation—helps geomorphologist Éric Fouache explain that the region’s many artesian wells made Jiroft’s development possible. (Mohammad Eslami-Rad / Gamma) |

Protecting Jiroft is an overwhelming task, for Madjidzadeh and his team have uncovered more than 250 separate sites across an area about the size of Austria or South Carolina. In the forested mountains 150 kilometers (90 mi) north of Jiroft, other archeologists have discovered copper mines that likely produced the ore for the copper and bronze artifacts unearthed in Jiroft’s gravesites. But so far, no one has pinpointed the chlorite mines.

French geomorphologist Éric Fouache, the team’s expert on reading the strata underlying the archeological sites, has discovered something else, however, which gave the Jiroft region a crucial advantage over Mesopotamia: water. A network of artesian wells supplied abundant water for irrigation and drinking even when the Halil River ran dry. With these sources of water, the inhabitants developed an agriculture based on calorie-rich date palms rather than the cereals of the Tigris and Euphrates delta, says Fouache. Palm groves also provided shade for extensive gardening.

“So it’s very possible the Jiroft people developed agriculture more easily than the Mesopotamians,” asserts the scientist.

Next year, Fouache plans on probing deeper to locate earlier remains buried by the region’s frequent tectonic upheavals. “Based on aerial photographs showing traces of past ground shifts, we expect to find older settlements not visible from the surface,” he says.

The primary Jiroft site consists of two mounds a couple of kilometers apart, called Konar Sandal A and B and measuring 13 and 21 meters high (41' and 67'), respectively. It was at Konar Sandal B that the archeologists dug out the seal impressions bearing writing. So far, the archeologists have excavated around nine vertical meters (28') of Konar Sandal B, discovering vestiges of a monumental, two-story, windowed citadel whose base covers nearly 13.5 hectares (33 acres). Madjidzadeh speculates that this imposing edifice once housed the city’s chief administrative center and perhaps a temple and a royal palace.

Finding the structure’s façade was difficult enough, but locating an entrance took the team weeks of digging through clay packed hard by millennia of rain-wash. “The mud is like stone,” Madjidzadeh complains. “You can hardly get a pick into it.”

This winter they stumbled across what appears to be the city’s main gateway, a squared-off earthen portal that closely resembles architectural details depicted on several chlorite vases. The team has also uncovered a second wall and vestiges of a third, with trenches exposing both private houses and another sizeable public building—perhaps a trading center.

“We know it’s another monumental building because the bricks are larger than the bricks used in private homes,” says Madjidzadeh.

According to the archeologist, the enormous ziggurat at Konar Sandal A was a tremendous feat of engineering that required four to five million bricks. Like its Sumerian counterparts, it was probably a sacred structure, a bridge between earth and sky, and it was probably topped by a room where the city’s protective god could woo his mortal consort, usually the wife or daughter of the ruler.

Although very little is known of the beliefs and rituals of Jiroft’s inhabitants, Madjidzadeh is convinced that the practice of burying the dead with a relative fortune in artifacts points to a well-organized religion with a priestly class that could command the efforts of craftsmen. Since the ancient Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh mentions scorpion-men similar to ones carved on Jiroft’s stone vases, the archeologist also suggests that parts of the Gilgamesh narrative circulated in Jiroft and may even have had their origins there.

|

|

| Madjidzadeh, in white hat at center, examines objects found near Konar Sandal B in a trench overseen by Romain Pigeaud of the Paris National Museum of Natural History. (Mohammad Eslami-Rad / Gamma) |

Another of the recent season’s top finds was the discovery by Marjan Mashkur, an Iranian researcher based in Paris, of shark bones and shells from the Gulf, 200 kilometers (120 mi) south. To Madjidzadeh, this find confirms that Jiroft merchants plied well-worn trade routes that led to the Gulf and on to Mesopotamia, dealing in chlorite vessels, lapis lazuli and other precious stones, and commodities fabricated in Jiroft.

Even at this relatively early stage, Madjidzadeh believes he has enough evidence to turn some of the fundamental precepts of Middle Eastern archeology on their head. The fabulous royal treasure excavated in the 1920’s by Leonard Wooley at the Sumerian capital of Ur, including the iconic, shell-encrusted ibex standing to nibble the leaves of a gold tree, may ultimately be traced back to the workshops of Jiroft, he says. So might chlorite vessels from Uruk, Mari and Soch.

“We’re not sure what gold pieces might have come from Jiroft,” says Pittman, “but some of the chlorite pieces in Mesopotamia may well prove to have been exported from this region of southeastern Iran.”

“Three years ago, I would have agreed with the common assertion that Mesopotamia was the cradle of civilization,” Madjidzadeh says. “Now I’m changing my mind to Jiroft, which, in its heyday, was just as important and as extensive as Sumerian civilization.”

For some in the field, this comparison sets off alarm bells.

Lamberg-Karlovsky is one of the skeptics. While the Harvard professor acknowledges the importance of the discovery of Jiroft and its chlorite vessels, he warns against hyperbole. “To imply that Jiroft is the most ancient Oriental civilization is way off the mark,” he argues. “In terms of actual material recovered so far, there is nothing earlier than 2500 BC, which is a thousand years later than the southern Mesopotamian world.”

Madjidzadeh, however, maintains that pottery found at Jiroft compares to shards from Tepe Yahya dated to 2800 BC. In addition, he reasons, it would have taken nearly half a millennium for Jiroft’s artisans to develop the degree of skill that attracted King Enmerkar’s envy in 2500 BC, an inference that pushes back the establishment of Jiroft to about 3000 BC. Unfortunately, carbon dating of the vases and pots—the most reliable technique for gauging the age of artifacts—is not possible at Jiroft, since there have been absolutely no traces of organic residue in any of the materials unearthed so far. The Harvard archeologist and others deprecate Madjidzadeh’s contention. “These are very tenuous conclusions,” says Lamberg-Karlovsky. “To try to put Jiroft on the same level as the Sumerian, Egyptian and Indus Valley civilizations, or even as the Bactrian material of central Asia, is to exaggerate and distort the archeological record. Jiroft is just not in the same ballpark.”

Based on his own chemical analyses of chlorite pieces from Tarut, Mesopotamia and elsewhere, Lamberg-Karlovsky states that the stone finds in those places were mined locally. He is thus wary of claims that Jiroft pottery was widely exported.

“It’s very significant that Jiroft was the center of production for huge numbers of chlorite vessels, but to say that the vessels found in Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula and the Iranian plateau came from Jiroft is patently false,” he declares.

Madjidzadeh counters that chlorite vessels may indeed have been produced elsewhere—but by itinerant artisans and stonecutters originally from Jiroft or local craftsmen imitating Jiroft styles.

For Rémy Boucharlat, chief of the French Center for Scientific Research in Tehran, it’s possible that Jiroft exported chlorite vessels to Mesopotamia and beyond. “Yet we still don’t know if the Mesopotamians carved their own imagery on unfinished stone or whether the iconography originated in Jiroft,” he says.

The Oriental Institute’s Alizadeh agrees that Jiroft artisans could well have traveled to Mesopotamia and other areas in the Middle East, but he too deflates some of Madjidzadeh’s more grandiose claims, including the assertion that Jiroft’s civilization predates Sumer’s. After examining the writing on the seal impression uncovered in February, the Chicago archeologist now doubts its authenticity. Compared to the sophisticated systems of writing that already existed in the region by 2500 BC, the Jiroft artifact presents “an extremely vague series of scratches,” he says.

“There’s great excitement about Jiroft because of the prodigious number of chlorite vessels found there, but the problem is that we don’t know anything about the makers of these objects,” argues Alizadeh. “What is significant is the similarity to designs found in Elamite culture, but to call Jiroft a civilization is not exactly true at this point. Possessing a major manufacturing workshop does not qualify the site as a civilization.”

Perhaps more exciting than the beautiful chlorite bowls, vases and cups, which after all reveal little information about the ancient inhabitants of Jiroft, says Boucharlat, are the newly excavated settlements and buildings. “We’re now entering a second phase of discoveries, one that goes beyond fine objects to a knowledge of the culture and its relatively high level of social organization and technical proficiency,” he explains.

Regardless of what impact the site ultimately makes on Middle Eastern archeology, there is no doubt that Jiroft is serving as a pilot program for Iranian professors and graduate students to work alongside international—mainly American and French—colleagues.

“Before the 1979 revolution, there was tremendous collaboration between Iranian and foreign archeologists,” notes Pittman, who first came to excavate in Iran more than 25 years ago. “We’re trying to pick up where we left off.”

As Madjidzadeh explains, “One of my conditions for inviting foreign archeologists to participate at Jiroft is that they accept Iranian students for training at their universities to learn updated techniques and western methods of teaching.” Now, however, the obstacles to such exchanges are not only on the Iranian side. Despite the University of Pennsylvania’s eagerness to train Iranian researchers, the US government has so far refused to grant them visas.

“It’s immensely frustrating,” Pittman admits. “Until the geopolitical fireworks calm down a bit, we’re not going to have any luck training them here in the us. And training the next generation of archeologists is the most urgent need by far for the country’s heritage.”

With more archeologists, Iran could again become a hotspot for the study of ancient civilizations. Certainly Madjidzadeh, who earns less in Iran than a skilled laborer does in France and who pays his own airfares between Nice and Tehran, is not in his profession for money. Ironically for an archeologist once hounded out of the country, local officials in the town of Jiroft are planning to name a square after him.

“I go to Iran because I love archeology and I love to help the nation,” he says. “It’s a part of my life I could never change even if I wanted to.”

|

|

You wouldn’t think that 6000-year-old bones and pottery shards would wow a bunch of 20-year-olds. But then you wouldn’t be reckoning with the archeology students at Shiraz University.

“I felt like a celebrity,” marvels Abbas Alizadeh. After a two-hour lecture to an auditorium packed with students and locals, the Iranian-born archeology professor from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago was besieged by questioners. “Finally, I had to escape,” he laughs. Alizadeh, who in 2001 pioneered renewed Iranian-us archeological ties, has witnessed firsthand the new surge to research and protect Iran’s 10 millennia of cultural heritage.

|

|

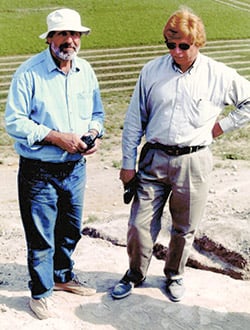

| It was Madjidzadeh’s longstanding belief that Jiroft was the third-millennium kingdom of Aratta that led Seyyed Mohammad Beheshti, deputy head of the Iranian Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization, wearing sunglasses, to offer the dig to him. |

It’s an urgent push that comes just in time. As the country’s population grows exponentially, monuments are being threatened by agricultural expansion and the roaring pace of industrial development.

“The Iranian economy is growing fast,” says Massoud Azarnoush, head of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research in Tehran. “New dams, irrigation networks, highways, railroads and factories are under construction everywhere. Once-remote areas are becoming accessible to development and agriculture, which are proving a serious menace to archeological remains.”

Although some 20,000 ruins are listed with the national center, Azarnoush estimates that the real total should be at least 10 times that—a staggering 200,000 historically significant archeological sites scattered around a nation the size of Alaska, or three times the size of France. It’s a heritage on a par with Egypt, Turkey or China. The sites range from tiny settlements and cemeteries to sprawling cities like Persepolis, capital of the Achaemenid kings, and the earthen citadel at Arg-e-Bam that in December 2003 was devastated by an earthquake.

Today, Tehran devotes some $20 million annually to archeology, according to Azarnoush, and it recently issued directives requiring building projects to avoid damaging archeological remains. “In many cases, we’ve succeeded in protecting uncovered sites and relocating highways, rail lines and dams,” he points out.

Still, there are thousands of sites at risk. Leading the list are extensive Elamite and Sassanian finds threatened by sugar-cane farming in Khuzestan province and pre-Bronze Age settlements at Tepe Pardis, on the outskirts of Tehran, whose bricks are being cannibalized for housing.

Other sites, like Jiroft, suffer rampant looting fueled by demand from international museums and collectors. “Of course, Iran is trying to stop this trafficking, but when museums with huge resources buy the objects, it doesn’t matter how much protection you have for the sites,” Azarnoush complains. Although the country’s chief monuments have armed guards, remote areas are patrolled by the “Guardians of Cultural Heritage,” an informal brigade of around 10,000 unarmed volunteers who report thefts to local police.

Key to reducing looting is public education similar to the efforts of Jiroft’s Yousef Madjidzadeh, together with a campaign to open up ongoing digs to visits from local residents and foreign tourists so they can see what a proper job looks like, and appreciate the emerging heritage.

“One of the first things we did at Bam after the earthquake was to create a passage through the ruins to permit visitors to see the damage to the citadel,” says Azarnoush.

|

|

| Sedigheh Piran produces an archeological drawing at the National Museum of Tehran. Such drawings “unroll” the decoration on three-dimensional objects and help archeologists visualize all of the design at once. (Mohammad Eslami-Rad / Gamma) |

And after some 25 years of isolation, the Islamic Republic is letting international teams back into the country, thanks in large part to Azarnoush and Seyyed Mohammad Beheshti, deputy head of the Iranian Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization (ICHTO). In August 2003, the government invited some 40 scholars, including professors from Harvard University, the University of Chicago and the University of Pennsylvania, to tour important sites and negotiate shared excavations.

“The Iranians are doing an outstanding job preserving some major monuments, undertaking new site surveys and trying hard to control looting,” observes Harvard’s Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky, who is now working with local archeologists at Bronze Age sites in the Atrak river valley near the border with Turkmenistan. “But this rebirth of international cooperation is immensely welcome. Isolation kills science.”

The key to the new agreements is that an equal number of Iranians and foreigners participate in the digs. “Under the Shah, outside expeditions came in, did their research and left,” Azarnoush explains. “There was virtually no scientific benefit for Iranians.”

Now, a team sponsored by the German Archaeological Institute is exploring copper mines from the fourth millennium BC discovered near Isfahan; Japanese archeologists are surveying the third-century city of Jalaliyeh; French researchers are poring over remains of Cyrus the Great’s fifth-century-BC capital at Pasagardae near Persepolis; and scientists from the University of Sydney are unearthing finds from second-millennium-BC Elamite sites near the Iraqi border.

For Azarnoush, who earned his doctorate from the University of California at Los Angeles, the decades of isolation proved an accidental boon in at least one respect.

|

|

| At the Jiroft dig site’s dormitory, University of Pennsylvania doctoral student Karen Sonik and Iranian colleagues discuss the progress of the second digging season. (Mohammad Eslami-Rad / Gamma) |

“It forced us to become more self-reliant,” he maintains. “Now we are better able to negotiate excavation terms on a more equal basis. We desperately need these outside collaborations in order to modernize our research and persuade our overly traditional archeologists that they have to broaden their teamwork with paleozoologists, paleobotanists, physicists and other branches of science.” Under these academic joint ventures, Iranians and foreigners also will cooperate on post-excavation conservation plans and bilingual publication of results, he adds.

Last May, in a gesture of goodwill, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago returned to Tehran 300 ancient Persian clay tablets that had been unearthed in the 1930’s. It was the first batch of several thousand cuneiform tablets that will be repatriated after the Institute finishes photographing them for a digital inventory.

Since the Oriental Institute’s Alizadeh first began traveling back to Iran in the mid-1990’s, he has begun to help set up an archeobiological laboratory in Tehran to house bones and seeds from various sites around the country. Earlier, he salvaged thousands of pottery shards that had lain underwater for decades in the cellars of a museum in Tehran, and created a databank to catalog them. He is training young archeologists to establish mini-databanks for the network of 52 regional research centers at principal excavations around the country.

What has struck the Chicago professor most during his time back in Iran is the insatiable hunger of students to pursue archeology despite the shortages of professors, equipment and training materials. “Even though I warn them they are going to be unemployed for a long time, maybe forever, they say they love it and won’t give up,” he explains. “It’s both sad and encouraging.”

|

|

Paris-based author Richard Covington writes regularly about culture, the arts and media for the International Herald Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian, Reader's Digest and other publications. He can be reached at richard.covington@free.fr. |