Written by Frank L. Holt

Illustrated by Norman MacDonald

Map by Mapping Specialists, Ltd.

With treasure in their saddlebags, three anxious

merchants from Bukhara raced madly for Peshawar.

With treasure in their saddlebags, three anxious

merchants from Bukhara raced madly for Peshawar.

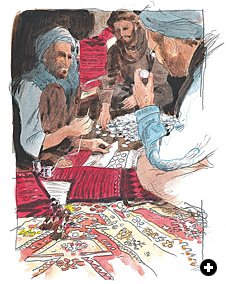

Wazi ad-Din, Shuker Ali and Ghulan Muhammud had

often traversed these dangerous trails across Afghanistan

to India. They normally traded in tea and silk, ever mindful that bandits lay in wait for wealthy men to make just one mistake. On this trip, the merchants made two.

The first occurred early in the journey when fortune offered them a rare but risky bargain. Villagers near Kobadian had recently unearthed a vast trove of coins and other antiquities, which they were selling to passersby. The merchants appraised the hoard’s value and calculated the risks of smuggling it to Peshawar, underestimating on both counts. Trading all they had for the treasure, they sewed thousands of gold and silver artifacts into their saddlebags and loaded them onto mules. Thus concealed, the treasure passed right through the army of Abdur Rahman—later the Amir of Afghanistan—and safely across the Hindu Kush.

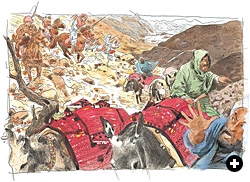

In Kabul, the merchants joined a caravan for added protection as they entered the last perilous passes between Afghanistan and India. Unfortunately, however, the secret of so great a treasure could not be kept in such close company. Once their story leaked, the merchants made their second mistake. Fearful of thieves among their fellow travelers, they and their servant dashed ahead of the caravan and took their chances alone. Ghilzai raiders quickly swooped down from the hills and found they had hit the jackpot.

At the top of a remote pass in Kapisa province, the Karkacha caves afforded the raiders a perfect refuge. As the captured merchants watched helplessly, the bandits spread out the saddlebags and began to divide their spoils. To apportion equal shares, they hacked some of the treasure into pieces. Four of the raiders suffered a similar fate when quarrels erupted over the loot. Thus distracted by blood and brawl, the criminals allowed one of the hostages to escape. He fled in darkness and made his way down to a British camp at Seh Baba.

At the top of a remote pass in Kapisa province, the Karkacha caves afforded the raiders a perfect refuge. As the captured merchants watched helplessly, the bandits spread out the saddlebags and began to divide their spoils. To apportion equal shares, they hacked some of the treasure into pieces. Four of the raiders suffered a similar fate when quarrels erupted over the loot. Thus distracted by blood and brawl, the criminals allowed one of the hostages to escape. He fled in darkness and made his way down to a British camp at Seh Baba.

On that May evening, Captain F. C. Burton was serving as regional political officer. He immediately sounded the alarm and led two troopers on a dangerous rescue mission. At midnight, the British burst into the cave and the startled bandits surrendered. Burton grabbed the merchants and their scattered treasure and retreated quickly, before the bandits realized they had surrendered to inferior numbers. Only later,

in the light of day, could it be determined that much of the treasure was still missing. Nonetheless, the grateful Bukharans escaped Afghanistan with their lives and at least part of their loot. In India they hawked their diminished wares to British soldiers and civil servants.

On that May evening, Captain F. C. Burton was serving as regional political officer. He immediately sounded the alarm and led two troopers on a dangerous rescue mission. At midnight, the British burst into the cave and the startled bandits surrendered. Burton grabbed the merchants and their scattered treasure and retreated quickly, before the bandits realized they had surrendered to inferior numbers. Only later,

in the light of day, could it be determined that much of the treasure was still missing. Nonetheless, the grateful Bukharans escaped Afghanistan with their lives and at least part of their loot. In India they hawked their diminished wares to British soldiers and civil servants.

The merchants’ account of their adventure leaves many questions unanswered. What they carried in their saddlebags was never inventoried before it spilled into the local bazaars. Archeologists naturally cringe at the haphazard ways that such materials typically get mixed together with other objects—some genuine, some fake—and, much

later, are all conveniently labeled as a single sensational find, in this case the “Oxus Treasure.” Bazaars no less than bandits play havoc with the historical evidence we so desperately need.

I hold in my hand one of the rarest treasures thought by some to have come from the merchants’ saddlebags, donated nearly 100 years ago to the British Museum by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks.

It appears to be an unusually thick silver coin or medallion;

it weighs 42.2 grams, or 1 11/43 troy ounces. No inscription identifies who made this medallion or why; the only writing stamped upon it is a mysterious monogram, so faint it is unclear whether it reads BAB or BA or AB. The designs on its two faces dazzle the eye with their intricate detail. On one side, a figure stands in full military array, clenching in his fist, as no ordinary human could, a lightning bolt. On the other side, a battle unfolds: A mounted warrior threatens two antagonists riding on a retreating Indian elephant. The picture speaks a thousand words, but refuses to give us names. What war is this? Who are the heroic combatants? Where and why was this medallion commissioned?

It appears to be an unusually thick silver coin or medallion;

it weighs 42.2 grams, or 1 11/43 troy ounces. No inscription identifies who made this medallion or why; the only writing stamped upon it is a mysterious monogram, so faint it is unclear whether it reads BAB or BA or AB. The designs on its two faces dazzle the eye with their intricate detail. On one side, a figure stands in full military array, clenching in his fist, as no ordinary human could, a lightning bolt. On the other side, a battle unfolds: A mounted warrior threatens two antagonists riding on a retreating Indian elephant. The picture speaks a thousand words, but refuses to give us names. What war is this? Who are the heroic combatants? Where and why was this medallion commissioned?

Many of the best numismatic minds of the past century have tackled this mystery. The first was Percy Gardner in 1887, whose identification of the standing figure has never since been challenged. Gardner recognized immediately the superhuman figure of Alexander the Great wielding the thunderbolt of his “divine father,” Zeus. But the elephant battle proved more baffling. In 1911, Barclay Head suggested that the Indian prince Taxiles, an ally of the Greeks, designed this medal to show his own heroic part in Alexander’s Battle of the Hydaspes River.

Many of the best numismatic minds of the past century have tackled this mystery. The first was Percy Gardner in 1887, whose identification of the standing figure has never since been challenged. Gardner recognized immediately the superhuman figure of Alexander the Great wielding the thunderbolt of his “divine father,” Zeus. But the elephant battle proved more baffling. In 1911, Barclay Head suggested that the Indian prince Taxiles, an ally of the Greeks, designed this medal to show his own heroic part in Alexander’s Battle of the Hydaspes River.

Through the same treacherous mountain trails that would later betray three merchants from Bukhara, young Alexander led an army of Greeks toward the frontiers of India.

Behind them lay a staggering record of conquest that changed the course of history; ahead stretched an exotic, unknown world that would test their king’s claim to divine invincibility. Not yet 30 years old, Alexander was already hegemon of Greece, king of Macedonia, pharaoh

of Egypt and lord of Asia. The huge Achaemenid Empire

of Persia had fallen to him in a series of spectacular battles, giving him greater wealth than the Greek world had ever known. He claimed direct descent from Hercules, Achilles and Zeus himself.

|

| Most of the decadrachm Alexander medallions are in private hands, lost to researchers. (This illustration is drawn from several museum specimens.) On one side, a rider chases retreating war elephants. On the other, Alexander, in military dress, clutches a lightning bolt, the symbol of his “divine father,” Zeus. Many of the coins have been found near Susa, in modern Iran, where accounts tell of an enraged Alexander throwing silver to his hungry horses. Actual size of the medallion is 34 millimeters (1 3/8 ") in diameter, comparable to a US half-dollar. |

|

| Smaller tetradrachm medallions have been found as well. Some show a riderless elephant on one side and, on the other, an archer whose bow and headdress mark him as part of the Indian forces Alexander defeated at the Hydaspes River. The initials “AB” may stand for Abulites, the Persian guardian of Alexander’s royal treasury at Susa. Actual size of this piece is comparable to a us quarter or a two-Euro coin. |

|

| Another tetradrachm shows an elephant with two riders and a banner. On the other side rolls an Indian chariot pulled by four horses. Does each medallion tell its own story—or did Alexander intend them to tell a story together? |

Restless, Alexander longed to reach the edge of the inhabited earth, which his tutor Aristotle had told him lay somewhere just beyond India. On his way there, Alexander joined Prince Taxiles, who hoped to enlist the Greeks’ aid in his own rivalries. The most formidable of his enemies was Porus, ruler of the neighboring kingdom across the Hydaspes River. When Porus refused to submit to Alexander, Taxiles’s hopes were realized—for he was sure the Greeks would cross the Hydaspes and overcome Porus on their way to the world’s end.

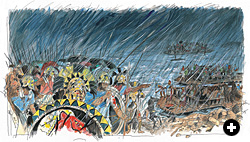

Alexander had certainly faced larger armies than Porus’s, and longer odds, but war in India presented two daunting challenges. First was the weather. The campaign against Porus took place during the monsoon, a demoralizing phenomenon for Mediterranean Greeks. Mere streams became torrents, flooding camps and flushing out poisonous snakes. Worst of all, the Hydaspes River itself roiled from the relentless rains and seemed impossible to cross. Second, there were elephants. Porus’s army included a large corps

of trained war-elephants whose very appearance alarmed

the Greeks. Trumpeting loudly, these mammoth beasts could terrify the cavalry and trample the infantry like no other weapon in the ancient world. They were the panzer divisions of the distant past.

Getting his army across the flooded Hydaspes in the face of this elephant menace has been called Alexander’s greatest achievement. Leaving in camp a large reserve as a diversion to hold Porus in place, Alexander marched under cover of rain and darkness to a carefully prepared crossing-point miles upstream. Concealed rafts and boats lay waiting to ferry his select force across the river before the enemy could react. A particularly severe thunderstorm masked the din

of embarkation. When he was finally alerted to Alexander’s unexpected deployment, Porus sent a son racing to meet

the emergency with chariots and cavalry. But, mired in monsoon mud, the Indian chariots failed miserably and Porus’s son died on the field. Porus then advanced with his main force of elephants, archers, chariots, and cavalry. Charge and counter-charge churned the sodden battlefield; the Indian archers struggled to steady their long bows against the wet ground. The elephants lost position and their mahouts fell under heavy fire. Wounded and riderless beasts stampeded through their own lines, where thousands of Indians lay dead or dying.

Conspicuous in the melee loomed Porus astride his own enormous elephant. He refused to give ground amid the

carnage until he was finally overcome by injuries and the

distressing sight of Alexander’s fresh reserves crossing the Hydaspes. While retreating, Porus noticed his old adversary, Prince Taxiles, in hot pursuit with a message from Alexander. As Taxiles neared, Porus turned upon him suddenly with

a javelin and frightened him away. Alexander then dispatched a better emissary who persuaded Porus to surrender.

As I look again at the silver medallion, I cannot understand why Taxiles would commission this beautiful memorial to the most embarrassing moment of his life.

Barclay Head had to be mistaken. To prove it, I can now reach into the collections of the British Museum and pull out another, better-preserved specimen of the elephant coin. Acquired in 1926 from Iran, this example shows the elephant’s riders more clearly, with the fighter—always the king in ancient India—in front, hoisting one spear and holding others in reserve. Both riders wear their hair tied high in Indian fashion. On the other side, something truly marvelous appears. Alexander stands as on the other specimen, but now I can see a flying Nike, goddess

of victory, placing a crown on the king’s head. Also, Alexander’s plumed helmet stands out boldly and matches that of the cavalryman on the other

side of the medallion.

I had recently seen the same details on another example in New York, obtained in 1959 by the American Numismatic Society. These additional coins make

it obvious that it is Alexander himself—and not Taxiles—at the heels

of Porus’s elephant. One ancient source describes such an episode, adding

that Alexander’s cherished horse died

of injuries during the chase. The medallion might therefore depict this “last stand” of the war-horse Bucephalus, as suggested by more than one modern scholar. On the other hand, most accounts of the battle describe Bucephalus’s demise under different circumstances,

and mention no personal duel between the kings. Clearly, the energy and confusion of war creates many versions

of the same event, and the passage of time tends to cloud our vision.

I had recently seen the same details on another example in New York, obtained in 1959 by the American Numismatic Society. These additional coins make

it obvious that it is Alexander himself—and not Taxiles—at the heels

of Porus’s elephant. One ancient source describes such an episode, adding

that Alexander’s cherished horse died

of injuries during the chase. The medallion might therefore depict this “last stand” of the war-horse Bucephalus, as suggested by more than one modern scholar. On the other hand, most accounts of the battle describe Bucephalus’s demise under different circumstances,

and mention no personal duel between the kings. Clearly, the energy and confusion of war creates many versions

of the same event, and the passage of time tends to cloud our vision.

Six months after defeating Porus, Alexander lounged aboard a ship back on the Hydaspes River, listening to the historian Aristobulus describe the great battle.

Aristobulus had thought to flatter his king with a fulsome tale of heroic feats. The entire company needed a lift after a long season of discontent. Alexander and his army had won the battle but wrangled over the peace, beginning with the fate of Porus. When Alexander asked his prisoner what should be done with him, the defiant rajah replied, “Treat me like a king!” Respecting the nobility of his foe, Alexander restored his crown and enlarged his kingdom. This gallant action galled the Greeks, who had

not risked their lives to leave Porus

in power. They resented, too, the march

ever eastward, away from home and into the monsoon-soaked unknown. Finally, on

the banks of the Beas River, the exasperated Greeks had threatened mutiny. Furious, Alexander sulked like Achilles and stormed like Zeus, but his men would not budge. The search for the world’s end was over; it was time to turn westward for home. It was a bitter disappointment which Alexander never forgot.

Aristobulus had thought to flatter his king with a fulsome tale of heroic feats. The entire company needed a lift after a long season of discontent. Alexander and his army had won the battle but wrangled over the peace, beginning with the fate of Porus. When Alexander asked his prisoner what should be done with him, the defiant rajah replied, “Treat me like a king!” Respecting the nobility of his foe, Alexander restored his crown and enlarged his kingdom. This gallant action galled the Greeks, who had

not risked their lives to leave Porus

in power. They resented, too, the march

ever eastward, away from home and into the monsoon-soaked unknown. Finally, on

the banks of the Beas River, the exasperated Greeks had threatened mutiny. Furious, Alexander sulked like Achilles and stormed like Zeus, but his men would not budge. The search for the world’s end was over; it was time to turn westward for home. It was a bitter disappointment which Alexander never forgot.

Lucian tells us that, to cheer his king on the journey home, Aristobulus read from his history a romanticized passage about the rout of Porus’s army. Alexander suddenly took offense. He snatched the scroll and tossed it into the very river that had witnessed the battle. The king snorted,

“I should throw you overboard as well, Aristobulus, since you dare fight my wars for me and have me killing

elephants with a

single thrust of my javelin!” Unlike Aristobulus, Alexander understood that history must tell the truth, nothing but the

truth and never

the whole truth.

To leave out offending facts was possible, but adding outright falsehoods—such as the effortless slaughter of elephants—was not, for lies undermine legends.

We can be sure, therefore, that when Alexander commissioned the elephant medallions, he considered their design

an accurate, if incomplete, depiction of the battle. Otherwise, like the manuscript of poor Aristobulus, the medallions would have been tossed aside.

Some experts insist that Alexander did throw at least some of this money away.

The reason stares back at me from the coin vaults of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Another medallion lies there, looking just like those in New York and London; beside it rest some stunning examples of smaller coins that add to our mystery. All of these extra elephant coins originated in an Iraqi hoard discovered near Babylon in 1973. They were quickly dispersed onto the antiquities market, fetching as much as $58,000 for a single medallion. A few, like those in front of me, settled into museum collections and set off fresh debates among scholars. The smaller varieties, often called tetradrachms, or two-shekel pieces, based upon their weight, add to the iconography of the larger decadrachms (or five-shekel) medallions. One series features

a riderless elephant on one side and an Indian archer on the other. The distinctive Indian bow, so large that it must be anchored against the archer’s foot, matches those attested in Porus’s army. The other variety shows an elephant with two riders, one of whom looks back as if being pursued. A great banner flutters overhead. The opposite side displays an Indian chariot pulled by four horses. Standing beside the charioteer, an archer fires a smaller bow at the enemy.

Scholars immediately called attention to the monograms on some of these smaller medallions, since they matched those on the decadrachms. These enigmatic Greek letters (bab or ba or ab, and x) might be the initials of the men responsible for minting these elephant artifacts. Experts searched among the names of all the bureaucrats of Alexander’s burgeoning empire for two individuals with the right initials who served together and might have minted coinage. This clever approach turned up “Abulites” and “Xenophilus,” men whose mintage was indeed thrown away by Alexander the Great.

The Persian nobleman Abulites had served King Darius III as guardian of Susa and its royal treasury.

When Alexander defeated Darius at the Battle of Gaugamela

in 331 BC, Abulites switched allegiance and surrendered his wealthy city to the Greeks. He thus received Alexander’s

pardon and was left in charge of Susa, but with the Greek soldier Xenophilus as his military overseer.

Six long years later, Alexander returned to Susa from India. The failure of his troops to follow him to the world’s end continued to vex the king, and the march homeward had not gone well. Along the way, Alexander had suffered a near-fatal wound when his soldiers became apathetic in battle. He agonized that the huge fleet he had built in India had been lost on its maiden voyage to Babylon. His land army endured horrendous losses on its march through the Gedrosian Desert. Then, returning to Mesopotamia in a sullen mood, Alexander suddenly discovered gross incompetence—even insurrection—among many high-living government officials who, in his absence, had plundered temples and tombs, abused the population and raised their own private armies. They had convinced themselves, wrote one ancient authority, that Alexander would never survive “the Indians and their elephants.”

Some modern scholars describe Alexander’s reaction

as a “reign of terror.” Many generals and bureaucrats were arrested and executed. Alexander allegedly killed Abulites’s corrupt son with his own hands. Abulites himself fell victim to a notorious lapse of judgment: When summoned to bring food and forage to Alexander’s hungry army, Plutarch tells us, Abulites delivered cash instead—eighty-five tons of silver coins, which the king tossed to his horses in outrage. As

the animals sniffed the silver in obvious disappointment, Alexander snarled, “What good are these provisions to us, Abulites?” An execution followed.

The more I investigate these elephant medallions, the greater the mystery grows.

Is this the mintage Abulites sent in a vain attempt to appease his irate king? Scholars now argue that a city bureaucrat could not have designed these artifacts on his own authority. Whatever the images on the discarded silver—be they elephant types or Alexander’s ordinary designs showing Hercules and Zeus—they must have had his royal sanction. Alexander’s coins and medallions reflect his own thoughts, not those of an Abulites or a Taxiles. So what message did he intend to convey on them? The large decadrachm medallions proclaim Alexander’s victory, with the king chasing down his Indian opponent in a display of Greek superiority. The smaller tetradrachm medallions, on the other hand, appear to showcase the power of Porus’s army, with no sign of the Greeks among the Indian archers, elephants and chariots. The contradiction seems obvious as I study more of these artifacts side by side in the vaults of the American Numismatic Society.

Curator

Martin Price of the British Museum looked at the antithetic images and decided that the Indian forces being displayed must represent not Alexander’s enemies, but his allies. Price saw in them Alexander’s dream of world brotherhood on the eve of the bloody battle against Porus. But the retreating elephants make no sense as allies. At the other extreme, Professor Alan Bosworth of the University of Western Australia has recently interpreted these coins as a

sinister warning to the Greeks back home who might choose to oppose Alexander’s regime: “Beware the consequences of revolt. The army which crushed Porus will easily crush you.” But the medallions in question never circulated in Greece. Their message must fall somewhere between brotherhood and brutality.

Martin Price of the British Museum looked at the antithetic images and decided that the Indian forces being displayed must represent not Alexander’s enemies, but his allies. Price saw in them Alexander’s dream of world brotherhood on the eve of the bloody battle against Porus. But the retreating elephants make no sense as allies. At the other extreme, Professor Alan Bosworth of the University of Western Australia has recently interpreted these coins as a

sinister warning to the Greeks back home who might choose to oppose Alexander’s regime: “Beware the consequences of revolt. The army which crushed Porus will easily crush you.” But the medallions in question never circulated in Greece. Their message must fall somewhere between brotherhood and brutality.

I offer now a new hypothesis that considers the medallions as parts of

a unified narrative. The tetradrachms lead us from the onset of the battle to

its aftermath, naturally with the dreaded elephants as the unifying subtext on each medallion: First we witness the chariots of Porus sent to stop Alexander’s deployment across the Hydaspes, then the caparisoned elephants starting to retreat with a nervous rider looking back. Next, the Indian archers wrestle with their heavy bows, and we see the stampeding elephants whose riders have all been killed. This story on the smaller medallions culminates in the powerful victory images on the large ones: Porus himself in retreat and Alexander crowned by Nike.

On a deeper level, the medallions also reveal Alexander’s revolutionary ideas about how he achieved this victory. As

we have noted, Greek historians quickly developed many versions of this great battle, some of which Alexander strongly disapproved. The key was to select only those facts that

flattered the king, while avoiding outright lies. Thus, when Alexander himself commissioned these artifacts, probably as rewards for service in the Indian campaign, he had to choose carefully which images to put on them. For the tetradrachms, he picked certain enemy units to illustrate key phases of the battle as he wished it to be remembered. He decided to ignore, for example, the important role of Porus’s cavalry. Clearly, in addition to the elephants, the archers and chariots had special relevance to Alexander’s own version of the battle. Only one extraordinary circumstance ties together these particular enemy forces—they were overcome because of the heavy rains, which had also “miraculously” concealed the Greeks’ crossing of the Hydaspes River. According to written accounts of the battle, Porus’s chariots suddenly got stuck

and the archers could not shoot effectively in the mire.

On a deeper level, the medallions also reveal Alexander’s revolutionary ideas about how he achieved this victory. As

we have noted, Greek historians quickly developed many versions of this great battle, some of which Alexander strongly disapproved. The key was to select only those facts that

flattered the king, while avoiding outright lies. Thus, when Alexander himself commissioned these artifacts, probably as rewards for service in the Indian campaign, he had to choose carefully which images to put on them. For the tetradrachms, he picked certain enemy units to illustrate key phases of the battle as he wished it to be remembered. He decided to ignore, for example, the important role of Porus’s cavalry. Clearly, in addition to the elephants, the archers and chariots had special relevance to Alexander’s own version of the battle. Only one extraordinary circumstance ties together these particular enemy forces—they were overcome because of the heavy rains, which had also “miraculously” concealed the Greeks’ crossing of the Hydaspes River. According to written accounts of the battle, Porus’s chariots suddenly got stuck

and the archers could not shoot effectively in the mire.

On these medallions, therefore, Alexander literally stole Zeus’s thunder. By wielding his father’s thunderbolt, the king called attention to and took credit for the divine tempest

that brought Greek victory. This was no ordinary triumph, and Alexander was likewise no ordinary leader. He had called upon superhuman powers to surprise his enemy, stop the chariots, disable the archers and doom the deeply feared elephants.

Not only did this interpretation of events flatter Alexander without prevarication, it also answered some of the bitterest complaints of his troops. In the months after

the Hydaspes battle, Alexander’s army grumbled loudly about the monsoon and the misery it caused.

These grievances played a part in the army’s refusal to follow the king deeper into India, to the end of the world. The elephant medallions offered the malcontents a powerful rebuttal by reminding them of their latest victory under Alexander’s divine guidance: The rain itself had been a weapon marshaled on their behalf. Thus, Alexander created this extraordinary message to inspire and reassure his troops in the difficult months

and years after the battle. He used these indelible images to explain and exploit his unique place in history. They show, quite simply, Alexander as he saw himself.

Gods die unexpectedly.

Not yet 33, Alexander lapsed into a deep coma and perished of uncertain causes on a hot June day in the old city of Babylon. He had pursued by choice a most challenging career, burning brightly but briefly in the tragic manner of Greek heroes.

He wished most of all to be remembered, and more than

a hundred subsequent generations have not disappointed him. His deeds have been sculpted, painted, written and romanticized more than those of any other monarch in the history of the world. Libraries and museums overflow with commentaries and canvases devoted to the momentous events of his career. We can read that, 350 years after the Hydaspes battle, the Indians still maintained a shrine to Alexander’s victory, complete with a living elephant that was said to have fought in Porus’s army. We can find in medieval European manuscripts an allegory casting Alexander as Christ and Porus as Satan. We read in Arab legend about the hero Dhul Karnayn (“The Two-Horned”), a possible reference to Alexander, some of whose coins depicted him with horns as a sign of divinity. We can enjoy imaginative engravings of the Hydaspes battle by Picart, an opera by Handel, and ultra-modern depictions in movies, magazines and comic books. There seems no chance that Alexander’s heroism will ever fade from our consciousness.

News arrives that more elephant medallions have been found in yet another Afghan treasure.

This time, an unexpected gold variety is reported. It may complete the remarkable story stamped by Alexander on the silver series. For this new evidence in our long saga—I don’t dare use the words “final chapter”—please stay tuned.

|

Frank Holt (fholt@uh.edu) is a professor of history at the University of Houston, most recently author of Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions (2003) and Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan (2005), both published by the University of California Press. |

|

Norman MacDonald (kingmacdonald@wxs.nl) is a Canadian free-lance artist who lives in Amsterdam. His coverage of the trial of Slobodan Milosevic in The Hague can be seen at www.wereldomroep.nl. |