The hallway that led to Dad’s library in our first-floor flat

in Damascus seemed to stretch for miles. I dodged pieces of furniture, dashing into the room lined with books in every direction. Mother was chasing me as fast as her feet could carry her, screaming, “Come here, you misbehaving little troublemaker!” Sitting in the corner of the room was my dad, wearing his abaya—his camel-hair house robe—reading. Never slowing down, I continued my run toward him. He opened the abaya, smiling, and I jumped in onto his chest, which seemed to my seven-year-old body the size

of a small oasis. He closed the abaya over me and returned to reading. I lay there, still as a rock, listening to the rhythm of his heartbeat. From my dark and cozy cocoon, I heard Mother enter the room and ask Dad where I was. He acted innocent of seeing me at all. Mother sounded doubtful, but he assured her that I must be hiding in another room.

I heard her moving a chair, then departing. As her footsteps faded, Dad started laughing, his chest vibrating.

He opened the abaya and looked down at me. “We did it again!” he grinned. He kissed me and squeezed me so tight

I could hardly breathe.

|

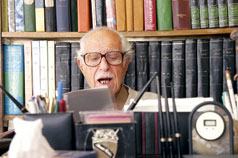

My father spent most of his time in this library. I remember Mom had to bribe him with his favorite meal sometimes, just to get him to eat. He told me that writing was as good as being in heaven.

I admire him for devoting his life to something so beautiful. |

This continued much of that year. I would misbehave—

a daily occurrence in my youth—and he would hide me from Mother, who was the disciplinarian in the family. But

I kept growing, and our cover was finally blown one day when Mother noticed that Dad looked rather too large.

Dad passed away last February 3 after 88 years of protecting me and my three siblings from all threats. Over the course of his career, he wrote more than 15 multivolume books on Arabic literature and poetry, some of which are used in universities throughout the Arab world. He spent

15 years writing the three-volume Mu‘jam al-Amthal

al-‘Arabiyya (Encyclopedia of Arabic Proverbs), published by the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies in Saudi Arabia, the most comprehensive book on

the subject. In 2004 Syria’s Ministry of Culture and Education honored him with the Outstanding Lifetime Achievement Award, the most prestigious literature award

in Syria, for his work in preserving the Arabic language.

My one regret is that, because I came to the United States, I missed being with him every second that I could. We had a rare connection.

We would talk for hours about anything: school, politics, religion, love and freedom.

He wanted me to live life abundantly.

He taught me many lessons, with one resonating the most: “Regardless of any circumstance, always do the right thing.” While not the most profound statement, it has been the hardest one to adhere to. “If you keep only one virtue in life, make it integrity. You will never regret it,” he would always say.

Dad, you lived and died with integrity, and while knowing my own faults and limitations, I will always do my best to be as pure as you wanted me to be.

I wear your abaya now, and with it I shield my own children, whenever they need a place to hide. |