|

| At the center of the museum is its three-story, tiled and gilded dome. |

Back in the early 1970’s, on the US television game show “To Tell the Truth,” celebrity panelists were asked to identify which of three guests had led five expeditions through Antarctica, had two mountains named in his honor and had done research that had proved the theory of continental drift. No one chose George Doumani, the diminutive Lebanese–American scientist who had to sit up straight to stay at eye level with the others.

ost Arab–Americans today are probably no more likely to know Doumani’s name than the television panelists were, or to know that he was later a candidate to become America’s first astronaut. (“They wanted someone who was small, who could fit in the space capsule.”) It’s a story Doumani tells proudly, but, as he explains, he was ultimately ineligible because he still held a Lebanese passport.

ost Arab–Americans today are probably no more likely to know Doumani’s name than the television panelists were, or to know that he was later a candidate to become America’s first astronaut. (“They wanted someone who was small, who could fit in the space capsule.”) It’s a story Doumani tells proudly, but, as he explains, he was ultimately ineligible because he still held a Lebanese passport.

Doumani is one of more than a hundred notable Arab–Americans whose achievements are now on display, along with some 500 artifacts, in Dearborn, Michigan at the Arab American National Museum. “Of all the things I have achieved, I think one of the greatest honors for me is to be recognized by my own people,” said Doumani at the museum’s opening on May 5.

Although Doumani never became an astronaut, another American of Arab heritage did: Christa McAuliffe. A teacher whose father had come to the us from Lebanon, she perished along with her crewmates on January 28, 1986, when the shuttle Columbia exploded on its ascent toward orbit.

|

| Above: On the new museum's opening day, scientist, antarctic explorer and almost-atstronaut George Doumani captivates young visitors in front of the display honoring his accomplishments. "One of the greatest honors for me is to be recognized by my own people," he says. Below: On May 5, with oversized scissors as ribbon-cutting props, Amre Moussa, secretary general of the Arab League, shakes hands with Dearborn Mayor Michael Guido, officially opening the Arab American nation Museum. |

|

|

| An opening-day crowd fills the museum's lobby. |

Organizers hope the Arab American National Museum will change how all Americans perceive Arabs.

Today, even Arab–Americans themselves “are often surprised to learn that someone well-known is of Arab–American heritage,” explains museum director Anan Ameri. Several Detroit newspapers that covered the museum’s opening began their stories by quoting Arab–American visitors who said they never knew that Doumani, McAuliffe, football quarterback Doug Flutie, opera soprano Rosalind Elias or others were of Arab heritage, or that achievements as important as the heart pump have Arab–American roots.

“There are so many stories in this museum. We have chosen to tell the stories through individuals, regular people who worked in auto plants or textile plants and in the fields, and through the eyes of great contributors, people who have changed the world, whom many people did not know were Arab–American,” says Ismael Ahmed, executive director of the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (access), which spearheaded the museum’s five-year fundraising and building drive.

Among the stories is that of Mansour Nahra, who immigrated to the us through Central America and fought alongside Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution—and later ran a furniture store. There is also Nagi Daifullah, an immigrant to California from Yemen who joined the United Farm Workers and died under police batons on August 15, 1973. There is Robert George, who served for more than 50 years as the official White House Santa Claus; his red and white costume hangs proudly on display. Near it is another Washington artifact: the portable Olivetti typewriter used early in her career by upi White House correspondent Helen Thomas. Also of Lebanese ancestry, Thomas covered the White House for 57 years until 2003 and, as the doyenne of the White House press corps, opened presidential press conferences with the first question and closed them with “Thank you, Mr. President.”

There is a tuxedo shirt from singer and actor Paul Anka; the original script of the final episode of the hit television series “M*A*S*H” from actor Jamie Farr; and the beads that actor Jim Carrey threw into the water at the beginning of the film “Bruce Almighty,” produced by Arab–American Tom Shadyac. One of the most poignant displays mentions the 154 Arabs who were on board the Titanic on April 10, 1912 when the ship struck an iceberg in the Atlantic Ocean and sank: Only 29 of them were among the 703 survivors.

“It’s nice to know that the accomplishments of our Arab people are appreciated in this country and to see them displayed in the museum,” says 14-year-old, Morocco-born Ahmed Mellouk, who attended on opening day.

Over the past three years, access staff, Ameri and museum curator Sarah Blannett have scoured the country to collect the museum’s 500 permanent exhibition pieces—a number they hope will continue to rise as the collection grows in coming years. Arab–American author and Kansas State University professor Michael Suleiman consulted with them on much of the material, which now fills three floors.

While there are Arab–American historical displays in many other museums, Blannett notes that they usually feature only a small cross-section of Arab– American history. “At the Smithsonian, for example, the Arab story is peripheral and a part of the larger immigration story to America,” she says. “Here, the focus is on being Arab–American.”

|

Left: "Even many Arab-Americans," says historian and museum director Anan Ameri, "are often suprised to learn that someone well-known is of Arab-American heritage." Ameri co-authored Arab Americans in Metro Detroit: A Political History. |

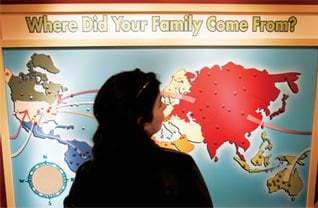

| Below: A wall-sized map shows the major pathways and periods of Arab immigration to the Americas. |

|

|

|

| A 1936 certificate of US citizenship granted to Emelia Hagopian lists her prior citizenship as "Syrian." |

|

She recalls that when Ameri spent three days with a Yemeni family in Delano, California, she was offered the artifact Blannett calls one of her personal favorites: a metal traveler’s trunk, “colorfully hand painted and of a type very common in India. The owner stuck labels from the vineyard where he worked to the trunk,” Blannett says. “The Arab–American story is not only about their experiences, but also about the things they brought with them and how they were used to add some comfort to their lives.”

The process, she says, will continue. “We’ve only touched the tip of the iceberg. This is just the first pass.” (She advises anyone who wishes to donate items to contact the museum, which will hand over a description of the item to its 67-member board. “We don’t want people just to send items in,” she says.)

|

| Above: Ruth Ann Skaff led much of the museum's nationwide, five-year fundraising campaign, and she secured for display the maquette of the bust used in the Kahlil Gibran Memorial, dedicated in 1991 on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, D.C. "I was thrilled that I was able to contact the museum and persuade them to save it and include it here," she says of the bust of the best-known Arab-American writer. Below: Museum membership coordinator Rafeef Hajj and Ameri share a moment of celebration. |

|

Suleiman, who is completing a comprehensive bibliography titled Arab– American Experience in the United States and Canada, says the process of identifying and documenting Arab– American history has been going on for decades, but that it picked up speed in 1967 immediately after the Arab-Israeli war.

“It was a wakeup call, especially for those Arabs who had been in the United States for a long time,” says Suleiman, who holds the title of “university distinguished professor.” “They de-assimilated and began to feel that, even though they had been in the country for over three generations, the ’67 war painted the Arabs and Arab–Americans all with one brush, and all in negative terms. As a result, the question of identity resurfaced and became very important again.”

To Suleiman, the museum is a natural outgrowth of this process of identity-building.

“The problem is the Arab–American community is not just one community. We are very diverse on many levels, such as Muslims and Christians, Lebanese, Palestinians, Egyptian and other Arab groups,” he says. “There are also small ethnic groups in the Arab world such as the Chaldeans, for example. Some Chaldeans want to be separate, although some feel they are a part of the Arab community. This was the biggest challenge that the museum faced; they sought to address it in meetings with the various community leaders in Detroit and around the country.”

Three years ago, as word began to spread about plans for the museum, many people offered to donate artifacts that were stored in closets, attics and garages throughout the country. Ruth Ann Skaff, who directed much of the museum’s fundraising, was one of them.

Standing in front of its display case, Skaff describe in a melodious Texas drawl the purple vestment worn by her father, Thomas Skaff, who crisscrossed the country conducting Orthodox services. Reverend Skaff was born in Sioux City, Iowa and his father was from the Beka’a Valley of Lebanon. Next to the vestment is a small percolator he used to make coffee as he visited Christian Arabs in seven parishes from Houston to St. Paul, Cleveland and Wichita.

“As you explore this more and more, there is no end to the discoveries,” says Ameri, a Palestinian who immigrated in 1971 and holds a doctorate from Detroit’s Wayne State University. “I think that 10 years from today, we will have so much more, and it will be even more proud.”

|

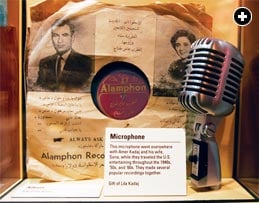

| Above: Helen Thomas, long doyenne of the Washington press corps, used this typewriter for dispatches early in her career; Below: popular singers Amer and Sana Kadaj used this microphone as they toured the nation in the decades after World War II. "We've been collecting for more than three years," says museum curator Sara Blannet, and "we've only touched the tip of the iceberg." |

|

|

| Visitors scrutinize displays that have drawn from more than 500 personal and family artifact donations nationwide. |

The tendency of prominent Arab–Americans to downplay or even hide their heritage, if only until they retire, is changing, say the museum officials, and they expect the existence of the museum to reinforce this growing cultural pride. A good example of the high-profile Arab–Americans who celebrate their heritage is Hollywood actor Tony Shalhoub, who in April helped inaugurate the museum’s pre-opening celebration banquet. Shalhoub stars in the popular television series “Monk,” and he played an Arab–American fbi agent in the 1998 film “The Siege.” The grandson of a Lebanese immigrant, Shalhoub makes the significance of the museum clear.

“I think that for the first time in our history in this country, we can begin to tell our own story of who we are, what we are about and where we have come from,” Shalhoub said at the banquet. “So much has been said about us that is not accurate, that’s wrong or worse. The Arab American National Museum is where our story can be told accurately and fully.”

The new three-story museum sits on what was formerly the site of a long-abandoned furniture store. Clad in polished Canadian marble and featuring a handsome fountain, the building takes on the look of what many observers describe as a “jewel box.” Panels of cast-stone arabesques enrich the interior, and the ceiling rises to a clerestory cupola above the two-story atrium, finishing with a rainbow of Moroccan tiles and Arabic calligraphy that repeats the museum’s name. The effect gives the building the look and feel of a mosque, without trying to imitate one.

Appropriately, the architects were the Dearborn-based Ghafari Associates, a firm established by an Arab–American from Lebanon. Designers and writers from Jack Rouse Associates in Cincinnati designed the interior exhibits.

On the ground floor, the permanent exhibit features Arab civilization and its contributions to science, medicine, mathematics and astronomy, and it displays Arab architecture and decorative arts. Also on the first floor is an auditorium and temporary exhibit space for Arab and non-Arab art. The inaugural show, “In/visible,” features 14 contemporary Arab–American artists; it runs through October 19.

In the main stairwell is a two-story map of Africa and the Middle East. From the balcony across from it, an interactive panel allows visitors to learn something about each of the 22 countries conventionally identified as predominantly Arab. The main library collection is on the second floor; it showcases Arab–American history in three thematic galleries titled “Coming to America,” “Living in America” and “Making an Impact.”

“Each gallery tells a story, beginning with the immigration of Arabs from 1500 to the present, continuing through their livelihoods in America, and concluding with the impact Arab–Americans have had on this nation,” explains Blannett, who holds a master’s degree in museum studies.

The museum is modeled after the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, says Ahmed, because the organizers felt that that museum best reflected the challenges Arab– Americans would face in showcasing their unique national identity. To drum up support and enthusiasm, he says, they set up working groups in 10 cities across the country and established touring groups to lecture on the museum and solicit both artifacts and financial contributions. They also showcased selected early exhibits.

|

|

|

| Top: One provocative gallery shows video interviews of real-life Arab-Americans on a screen that both pushes out from, and is confined by, side walls covered with common negative stereotypes of arabs and Arab-Americans. Left: Nozmi elder, 8, and his sister Madina Elder, 11, of Dearborn push buttons to illuminate parts of the interactive map of the countries of the Arab world. Right: The second story of the museum wraps around the space bneath the building's dome. |

|

“We looked at many museums and ideas,” explains Ahmed. “We worked with [the Japanese American National Museum] very closely to understand their success.”

Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick and Dearborn Mayor Michael Guido were among the dignitaries attending the ribbon-cutting on opening day. Guido said his city had benefited from the contributions of Arab–Americans, adding, “The museum presents the immigrants’ story in a way that is universal. That’s especially relevant to Dearborn, because we are home to people from 80 nations, cultures and ethnic groups.”

Other officials attending the opening were us senator Carl Levin of Michigan; Michigan lieutenant governor John D. Cherry, Jr.; Amre Moussa, secretary general of the League of Arab States; Arab League ambassador Hussein Hassouna and Bader Omar Al-Dafa, ambassador to the us from Qatar.

Other officials attending the opening were us senator Carl Levin of Michigan; Michigan lieutenant governor John D. Cherry, Jr.; Amre Moussa, secretary general of the League of Arab States; Arab League ambassador Hussein Hassouna and Bader Omar Al-Dafa, ambassador to the us from Qatar.

Among the more than 2000 people in the general audience on opening day was Saffiya Shillo, board chairman of Chicago’s Arab American Family Services. She and seven other women drove five hours to attend. “I had heard about some of the people in the museum and many of the things they credit to Arab–Americans, but there is so much more I did not know. It’s nice to know that this museum is here so that our achievements can be recorded.”

And Amna Mohammed, a grandmother who waited four hours to enter on opening day, stopped and stared at one photograph from the mid-20th century. “I know that person!” she exclaimed. “He’s from the Judeh family. I haven’t seen him in years!”

|

| Above: Seven women who came to the museum's opening by bus from Chicago pose on the street before heading home. Below: A statue of former Deaborn mayor Orbille Hubbard that stands in front of City Hall now appears to gesture across the street to the Arab American Museum. |

|

Few familiar with the history of metropolitan Detroit miss the irony of the museum’s location directly across Michigan Avenue from Dearborn’s City Hall. It was from there that, from 1942 to 1978, Mayor Orville Hubbard, one of the most outspoken segregationists north of the Mason-Dixon line, led a high-profile campaign to expel Arab– Americans from Dearborn—along with other non-white residents.

As more and more Arabs came to Dearborn, lured by the jobs at Henry Ford’s automobile factories, Hubbard began to rezone their neighborhoods to “industrial use only,” which forced the Arab owners to sell their properties to the city. Those who remember those battles, like Ismael Ahmed of access, say that the focus of the fight at the time was simply to secure fair buyout prices for the homeowners. Nearly half of the Arabs who had settled in Dearborn through the 1970’s left in those years.

But, according to Ahmed, Arab– American activists filed legal challenges to Hubbard’s policies, and by the time he left office in 1978, Arab immigration to the Detroit area had again accelerated, and many of the newcomers again settled in Dearborn. The battles forged strong community alliances, and the resulting support networks have continued to serve well to this day. Was this Hubbard’s gift? “In a way, Arab–Americans contributed greatly to the revitalization of East Dearborn, which had been marked by many abandoned buildings, vacant lots and unused properties,” Ahmed says. “Arab–Americans made this area their home, rejuvenating the economy for all. The very fact of choosing an abandoned property like the Leeds Furniture store, where the museum now stands, is a way in which Arab–Americans have given back to the larger community.”

Today, major thoroughfares in Dearborn, including Michigan, Schaefer and Warren Avenues, feature rows of Arab restaurants and other businesses; overhead are billboards that feature Arabic writing, Arab faces and Arab names. About 34,000 of Dearborn’s 100,000 citizens trace their ancestry to one of the 22 Arab-world countries, most to Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq and Yemen. There are more than 430,000 Arabs throughout Michigan, the largest concentration of Arab–Americans in a single state. About 40 percent live in Wayne County, which encompasses both Detroit and Dearborn.

“For the first time in American history, people can now come to one place and see the vast, rich contributions Arabs have made to this country,” said Congressman Ray LaHood of Illinois, who traveled with his wife from Peoria to attend the opening. “It is appropriate that the first Arab museum opens here in Dearborn. This is the capital of Arab America.”

smael Ahmed’s drive to build the Arab American National Museum comes from his knowledge that, to achieve influence in America, ethnic communities have always organized—and his belief that organizing is still the path today. Son of a man who immigrated illegally into the United States from Egypt at age 10, Ahmed was born in Brooklyn in 1947 and, after his mother remarried, moved to Detroit about the same time the battles with Mayor Hubbard were peaking. smael Ahmed’s drive to build the Arab American National Museum comes from his knowledge that, to achieve influence in America, ethnic communities have always organized—and his belief that organizing is still the path today. Son of a man who immigrated illegally into the United States from Egypt at age 10, Ahmed was born in Brooklyn in 1947 and, after his mother remarried, moved to Detroit about the same time the battles with Mayor Hubbard were peaking.

“My father moved to Detroit to set up an Egyptian record store,” recalls Ahmed. “I lived in Arab–American communities pretty much my whole life, first in New York and then in the Detroit metropolitan area. But like most young people, at first I was interested in anything but Arab culture or being Arab.”

It was while serving in the us Army during the Vietnam War that Ahmed discovered his activist calling. “I found in Detroit this powerful sense of community around me that gave me support and a sense of home and belonging. I became active in the community, working on political and social efforts, including against urban renewal and for fairness in the Middle East. We fought City Hall over issues of urban renewal.”

Ahmed was a co-founder of access, and he became its executive director in 1983, a position he has held ever since.

Now, “being across from City Hall does have significance,” he says, but “the museum isn’t about the history of wrongs. Rather, it is about how far Arab–Americans in the Detroit region have come. Arab–Americans have come full circle in this city, and being across from City Hall says that.” |

he Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services, or access, was founded in 1970 and continues to set the national standard for achievement in Arab–American community empowerment. Its founders were auto workers, engineers, lawyers, teachers, entrepreneurs and students who opened a storefront in southwest Detroit. From there, the volunteers served all comers with English-language instruction and tax assistance. A community activist named George Saad paid the rent for several years until the organization started to raise its own funds and obtain its own grants. he Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services, or access, was founded in 1970 and continues to set the national standard for achievement in Arab–American community empowerment. Its founders were auto workers, engineers, lawyers, teachers, entrepreneurs and students who opened a storefront in southwest Detroit. From there, the volunteers served all comers with English-language instruction and tax assistance. A community activist named George Saad paid the rent for several years until the organization started to raise its own funds and obtain its own grants.

| Top: Hisam Ajouz, 17, gets a pre-football season checkup from Leila Hadda, MD, at the ACCESS health clinic. Right: Sahar Al-Mosawi looks over a practice test with ACCESS bilingual counselor Adnan Almurani. Below: The lobby of the 35-year-old Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services. |

|

In 1973, the Yemeni Benevolent Association purchased a building and gave access free space in it. The number of support services access provided increased dramatically, and in 1975 it received its first grant under the federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, which provided money to support public and private job training; then, despite political tensions under Mayor Hubbard, access applied to the City of Dearborn for additional funding.

In 1978 and again in 1984, the access offices were destroyed by fire. In 1978 and again in 1984, the access offices were destroyed by fire.

Despite such setbacks, access continued to grow, and today, in addition to being the driving force behind the Arab American National Museum and continuing to offer language, medical and employment services, access has established a cultural arts programand founded a national arts network, and has trained experts to speak to other Americans on national questions ranging from welfare reform to immigration policy. |

Bashara Kalil Forzley was born in 1883 in Karhoun, Lebanon. When he was 14, his mother pinned to his jacket the address of a cousin who had emigrated to Worcester, Massachusetts, and sent him to America to find work that would allow him to support his family back home. As he set off from Beirut in 1897, his mother gave him this advice: “Always associate yourself with people who are your elders; do not indulge in liquor, smoking, dating or partying; and do not forget your folks at home. If you live and succeed, we also will succeed by our manifested happiness.”

Elsie Safady’s mother, Nora Roum, arrived at Ellis Island from Syria seven months pregnant. She was detained for observation because of an eye condition. She didn’t like the hospital’s food, and an uncle brought her some Arab food—cheese, olives and pita bread. Nora placed the food in a cabinet beside her bed and, during the night, opened the cabinet to eat—only to find a rat feasting on her food. Nora screamed in fright and soon went into labor. She named her baby Elsie, for the island on which she was born. Elsie Safady’s mother, Nora Roum, arrived at Ellis Island from Syria seven months pregnant. She was detained for observation because of an eye condition. She didn’t like the hospital’s food, and an uncle brought her some Arab food—cheese, olives and pita bread. Nora placed the food in a cabinet beside her bed and, during the night, opened the cabinet to eat—only to find a rat feasting on her food. Nora screamed in fright and soon went into labor. She named her baby Elsie, for the island on which she was born.

Influenced by stories of other immigrants who had returned to the village, Dieb Karam, his wife and seven other young men decided to leave for America in 1907. On the day of their departure, they left the village on foot. Deib’s father, Becos Elias Karam, followed slowly behind, calling out after his son, “Dieb, call my name.” Dieb would call back, “Papa, Papa, I hear you.” As the group crested a hill, Becos yelled, “Dieb, call my name one more time, for I know this will be the last time I will hear your voice!” When the group was out of sight and Becos could no longer hear his son’s voice, he fell to the ground and wept. It was indeed the last time he saw his son or heard his voice. Influenced by stories of other immigrants who had returned to the village, Dieb Karam, his wife and seven other young men decided to leave for America in 1907. On the day of their departure, they left the village on foot. Deib’s father, Becos Elias Karam, followed slowly behind, calling out after his son, “Dieb, call my name.” Dieb would call back, “Papa, Papa, I hear you.” As the group crested a hill, Becos yelled, “Dieb, call my name one more time, for I know this will be the last time I will hear your voice!” When the group was out of sight and Becos could no longer hear his son’s voice, he fell to the ground and wept. It was indeed the last time he saw his son or heard his voice.

“When we came to the United States in 1987, we brought nothing with us, just one set of clothes for each person. Before coming to the States, we were moving from one place to another as refugees. We left our village, Aitaroun, in 1978 because of the Israeli invasion of South Lebanon..., and we took nothing with us; we just fled for our lives. Because of the Lebanese civil war and the Israeli occupation, we just kept moving from one place to another, seeking safety. When the bombing would start, usually at night, we would run to a shelter, if there was one…. We would grab our blankets, pillows, a radio and a flashlight and just run…. When I was ten years old, we stayed in one shelter for a whole month…. We lived on boiled potatoes. That is why, when we came to America, like other Lebanese immigrants of the time, we came with nothing.”

Around the turn of the century, Mama and Papa Joe Korkames came to the us from Lebanon, eventually settling in Fort Smith, Arkansas, where they opened “The Famous Café.” Their chili became so popular that Papa Joe began packaging it for his customers in one-pound, hand-wrapped bricks. Papa Joe then decided to market the chili in grocery stores. Sales were so good that, in 1935, Papa Joe established The Famous Chili Company. Today, the company is still owned and operated by the Korkames family, now in its third generation, and the recipe is still Papa Joe’s. Around the turn of the century, Mama and Papa Joe Korkames came to the us from Lebanon, eventually settling in Fort Smith, Arkansas, where they opened “The Famous Café.” Their chili became so popular that Papa Joe began packaging it for his customers in one-pound, hand-wrapped bricks. Papa Joe then decided to market the chili in grocery stores. Sales were so good that, in 1935, Papa Joe established The Famous Chili Company. Today, the company is still owned and operated by the Korkames family, now in its third generation, and the recipe is still Papa Joe’s.

Born in 1912 in Lansing, Michigan to Lebanese immigrant parents, Richard Caleal began drawing pictures of automobiles at the age of seven. Self-taught and passionate about design, Caleal worked at Hudson, reo, Cadillac and Packard before going to Studebaker to become a member of the famed Raymond Loewy design team. In 1946 he began working as a free- lance designer for George Walker, who had been awarded the contract from Henry Ford ii for the design of the 1949 Ford. Working on the kitchen table in his small bungalow in Mishawaka, Indiana, Caleal designed and completed his prototype quarter-scale model, which was personally selected by Henry Ford ii to become the 1949 Ford. Referred to as “the car that saved an empire,” the 1949 Ford helped save Ford Motor Company from financial trouble, and earned Ford an astounding $177 million profit that year. Moreover, Caleal’s hyper-smooth, slab-sided design set the trend for the future of automobile styling. Born in 1912 in Lansing, Michigan to Lebanese immigrant parents, Richard Caleal began drawing pictures of automobiles at the age of seven. Self-taught and passionate about design, Caleal worked at Hudson, reo, Cadillac and Packard before going to Studebaker to become a member of the famed Raymond Loewy design team. In 1946 he began working as a free- lance designer for George Walker, who had been awarded the contract from Henry Ford ii for the design of the 1949 Ford. Working on the kitchen table in his small bungalow in Mishawaka, Indiana, Caleal designed and completed his prototype quarter-scale model, which was personally selected by Henry Ford ii to become the 1949 Ford. Referred to as “the car that saved an empire,” the 1949 Ford helped save Ford Motor Company from financial trouble, and earned Ford an astounding $177 million profit that year. Moreover, Caleal’s hyper-smooth, slab-sided design set the trend for the future of automobile styling.

After living in the us for 82 years, Mary Korkmas finally took the oath of allegiance to become a United States citizen on June 25, 1986. Korkmas had arrived at Ellis Island from Greater Syria with her mother in 1904, when she was just three years old. Unfortunately, her entry papers were among countless others destroyed in the 1916 fire at Ellis Island, and it was not until 1950 that she realized that she was not a citizen, as she had thought. After three failed attempts to gain her citizenship, Mary turned her attention back to raising her family in Texas. In 1984, Mary met a friend who helped her approach the citizenship process again. Although she only became a citizen officially at age 85, she says she has felt like a citizen for all 82 years.

|

|

Ray Hanania (rayhanania@aol.com) is an award-winning national syndicated columnist, standup comedian and author. His books include Arabs of Chicagoland (Aracadia Publishing) and a humorous look at the unique experience of Arabs in America, I’m Glad I Look Like a Terrorist: Growing Up Arab in America. |

|

Eric Seals (seals@freepress.com) is a staff photographer at The Detroit Free Press. He recently won the annual Dart Award for Reporting on the Victims of Violence for a six-month project covering homicides in Detroit. Seals frequently travels to the Middle East for news and feature assignments. |