|

|

|

Above, from top: Milton Hatoum is one of Brazil’s leading novelists. Carlos Ghosn is president and CEO of Nissan. Immunologist Peter Medawar, MD (1915–1987) shared the 1960 Nobel Prize for medicine.

from top: bel pedrosa; ap/wide world photos; bettmann / corbis. |

In Brazilian author Milton Hatoum’s best-selling novel Dois Irmãos, identical twins Yaqub and Omar— of Lebanese origin, like the author—vie for their mother’s love growing up in the Amazon River port of Manaus. Hatoum says he drew on his own upbringing in that city of 1.5 million people—a city whose history is intertwined with that of the thousands of Arab immigrants who began moving to the Amazon jungle more than 120 years ago, lured by the rubber boom and promises of economic opportunity.

“I touch on the theme of immigration in my city, Manaus, and how those immigrants integrated into Brazilian society. But there’s no nostalgia here concerning Lebanon,” Hatoum says. “The children of immigrants in Brazil don’t feel this belonging to a separate community. They already feel Brazilian. I’ll give you an example: No one in my family married other children of Arab immigrants. Here, we don’t think of ourselves as Lebanese–Brazilian or Japanese–Brazilian or whatever. We’re all just Brazilians.”

Hatoum, 53, is considered one of the greatest contemporary writers of Brazil. His first novel, Relatos de um certo Oriente (published in English as The Tree of the Seventh Heaven, then Tale of a Certain Orient) won the Jabuti, Brazil’s equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, in 1990. So did Dois Irmãoes, his second novel, which in 2002 was published in English as The Brothers and has since been translated into German, French, Dutch and Arabic.

“After I published Dois Irmãos, [Brazilians] of Italian background told me that the same things happened with their children,” says Hatoum. “Literature is universal. My novel depicts a local situation that can apply to people of all national origins.”

|

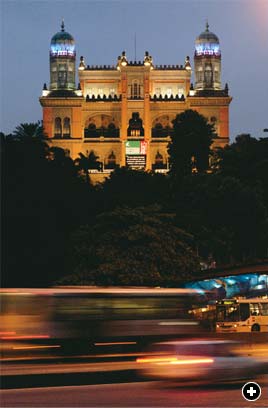

| In Rio de Janeiro, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation has been instrumental for more than a century in the battle against epidemic diseases; its headquarters, completed in 1908, take architectural inspiration in part from the Alhambra. |

atoum’s widespread acceptance in Brazil underscores the country’s popular melting-pot image, but it’s also a reminder of how pervasive the Arab influence has come to be throughout this vast nation, which accounts for nearly 48 percent of South America’s land mass and 51 percent of the continent’s population. Of Brazil’s 186 million inhabitants, an estimated nine million, or five percent, can point to roots in the Middle East. Brazil has more citizens of Syrian origin than Damascus, and more inhabitants of Lebanese origin than all of Lebanon. Of the nine million, some 1.5 million are Muslims; the majority are Orthodox Christians and Maronites. Yet none really stands out as a distinct ethnic minority in this Portuguese-speaking nation of sun, sand, soccer and samba.

atoum’s widespread acceptance in Brazil underscores the country’s popular melting-pot image, but it’s also a reminder of how pervasive the Arab influence has come to be throughout this vast nation, which accounts for nearly 48 percent of South America’s land mass and 51 percent of the continent’s population. Of Brazil’s 186 million inhabitants, an estimated nine million, or five percent, can point to roots in the Middle East. Brazil has more citizens of Syrian origin than Damascus, and more inhabitants of Lebanese origin than all of Lebanon. Of the nine million, some 1.5 million are Muslims; the majority are Orthodox Christians and Maronites. Yet none really stands out as a distinct ethnic minority in this Portuguese-speaking nation of sun, sand, soccer and samba.

“As Arabs, we have been able to integrate very easily into Brazilian society,” says businessman Faisel Saleh, a third-generation Lebanese Muslim whose heritage also includes Portuguese and Polish elements. “We are a very hardworking community. Arab people came here because of wars and instability in their own countries of origin, but—like all ethnic groups in Brazil—we try to maintain our culture, especially our social customs and cuisine.”

Saleh was born and raised in Foz do Iguaçu, which is famous as the gateway to Iguazu Falls, one of South America’s biggest tourist attractions. It also has one of Brazil’s largest Arab populations.

Saleh commutes several times a week across the Ponte Internacional de Amizade—the International Friendship Bridge—to Ciudad del Este, Paraguay. There, he runs an electronics shop just down the street from La Petisquera, a duty-free shop owned by another Brazilian–Lebanese businessman, Mohamad Said “Alex” Mannah.

Unlike Saleh, Mannah was born in Lebanon, in the Beka’a Valley village of Ba’aloul. He and his brother came to Brazil in 1970, first settling in the southern state of Santa Catarina.

“I resettled in Foz do Iguaçu because my aunts and uncles were already living there,” says Mannah, who today owns three retail stores in the tri-border area where Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina meet. “There is no discrimination against Arabs. In Brazil, discrimination is a crime, but in any case we have never felt like foreigners. The young people, those under 30 or 40, don’t even speak Arabic.”

|

| From left: During the opening of the 2003 Lebanese International Business Council conference in São Paulo, São Paulo governor Geraldo Alckmin, former Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri, president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and first lady Marisa da Silva listen to the Brazilian national anthem. On a 2004 walking tour of São Paulo, Portuguese prime minister José Manuel Durão Barroso, left, was guided by governor Geraldo Alckmin. In 2001, the Syrian–Lebanese Hospital in São Paulo dedicated a painting of its founder, Daher Cutait.

FROM LEFT: MAURICIO LIMA / AFP / GETTY IMAGES; AP / WIDE WORLD PHOTOS; HELVIO ROMERO /ANGENCIA ESTADO-BRAZIL |

That’s ironic considering that some 100 Arabic words have found their way into Portuguese—arroz (rice), alface (lettuce) and açucar (sugar) are examples. Yet Mannah is right: According to Mamede Jarouche, professor of Arabic and head of the University of São Paulo’s Department of Oriental Studies, only 50 or so students at the university—one of Brazil’s largest—are majoring in Arabic studies, and of that group, only a handful are of Arab origin.

This scarcity of Arabic speakers came to light in May when President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva hosted an unprecedented summit among 12 South American countries, the 22 member states of the Arab League and 1250 entrepreneurs—and found that Brazil could produce only three native-born interpreters. To meet the need, 22 more were flown in from Egypt.

|

The Syrian–Lebanese Hospital

The Syrian–Lebanese Hospital (Hospital SírioLibanês) in São Paulo is one of the leading legacies of the Arabs of Brazil. Founded by women from the Syrian– Lebanese community, its original building was constructed in 1940, but three years later it was requisitioned by the government to house military cadets. In 1959, it was returned to the founders. It was not until 1965 that it was officially inaugurated. It then grew to become one of the most capable and respected hospitals in Latin America, and in 1992 expanded to become one of the largest in Brazil. Since then it has become a technological leader as well, carrying out the first telesurgery in the southern hemisphere in 1999 and, in 2004, launching an interdisciplinary program for preventive medicine. Today it employs some 2500 professionals in 60 specialties, and can carry out some 50 surgeries daily. epitacio pessoa / agencia estado-brazil |

ccording to historians, the first Muslims in Brazil were not Arabs but West African slaves brought by the Portuguese, who began colonizing Brazil in the early 1500’s. Arabs from what are today the countries of Syria and Lebanon didn’t begin arriving until about 1880, at the height of the Amazon rubber boom that figures so prominently in Hatoum’s novels.

ccording to historians, the first Muslims in Brazil were not Arabs but West African slaves brought by the Portuguese, who began colonizing Brazil in the early 1500’s. Arabs from what are today the countries of Syria and Lebanon didn’t begin arriving until about 1880, at the height of the Amazon rubber boom that figures so prominently in Hatoum’s novels.

Settling first in Manaus, Belém and other Amazon port cities, the Arab immigrants also worked as itinerant peddlers, hawking their wares from door to door much as they did in Chile, Honduras, the United States and elsewhere in the Americas. In 1897, the first Arabic-language newspapers appeared in São Paulo; the same year, an Arab charitable organization known as the Sociedade Maronita de Beneficiencia was established.

By the early 1900’s, many Arab immigrants were settling in Brazil’s southern provinces, especially in Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais and São Paulo. The latter city grew to become home to some 38 percent of them by 1920, and by 1940 the proportion was up to nearly 50 percent.

Many of these immigrants settled in São Paulo’s Rua 25 de Março district, where they typically set up small textile and dry-goods shops. The most successful entrepreneurs among them eventually moved out to the better neighborhoods of Vila Mariana and Avenida Paulista.

Like other immigrant groups arriving around the same time, the Arabs made every effort to send their children to the best Brazilian schools, and they went on to become some of the country’s top doctors, lawyers, business leaders and politicians.

This accounts for the country’s most important Arab institution: the Arab–Brazilian Chamber of Commerce (CCAB is the acronym in Portuguese), headquartered on the 17th and 18th floors of a skyscraper along Avenida Paulista, in the heart of São Paulo’s financial district.

“Brazil’s Arabs generally came from the mountains and rural areas of Syria and Lebanon. They were not educated, but they worked very hard and were very good salesmen,” says Paulo Atallah, a civil engineer and former president of the CCAB. “Their dream was that their children would be doctors, lawyers or engineers.”

The CCAB, founded in 1952, today has 3000 members representing companies in agribusiness, banking, manufacturing, petroleum, retail sales, textiles, tourism and telecommunications. It runs a bilingual news agency, Agência de Noticias Brasil–Arabe, which it created “to fill the communications gap between Brazil and the 22 Arab countries that are represented by the chamber.”

Like the 47-year-old Atallah, many other first-, second- and third-generation Brazilian Arabs have become prominent economic and political leaders. These include Silvio Santos, owner of SBT, Brazil’s second-largest television network; Abilio Diniz, CEO of the Pão de Açucar supermarket chain; Paulo Antônio Skaf, president of the São Paulo State Federation of Industries, and Faisal Hammoud, founder of the luxury goods conglomerate Grupo Monalisa. Hammoud, 59, came to São Paulo in 1968 and, within four years, had established Grupo Monalisa’s first store and earned enough to send for his five brothers. It wasn’t long before the company opened its first centralized distribution office and established Home Deco, an in-house company for manufacturing showroom furniture.

In the early 1990’s, the Hammoud brothers inaugurated an overseas office in Miami and launched the Aphrodite Boutique chain of luxury retail shops, of which there are now eight in three South American countries. Hammoud has been among the leading financiers of the post–civil war rebuilding of Beirut.

“For those people who came to Brazil during Lebanon’s civil war, it was much more difficult to integrate. The war not only destroyed property but people’s minds as well,” he says. “But people who came a generation or two ago, or at the beginning of the century, are totally integrated. We don’t feel any difference between ourselves and other Brazilians.”

In 1997, then-President Fernando Henrique Cardoso awarded Hammoud one of Brazil’s highest honors, the Order of Rio Branco, for his involvement in negotiations leading to the founding of the Montevideo-based southern common market, Mercosur, of which Brazil is a founding member.

Asked how he became so successful, Hammoud replies matter-of-factly, “Because I am hardworking and honest. When I’m alone in a room with the door closed, I can look in the mirror and be happy.”

Other Brazilians with roots in Lebanon have risen in politics, including Ibrahim Abi-Ackel, who served as justice minister under President João Figuereido, and Osmar Chohfi, Brazil’s former deputy minister of foreign affairs. (The list also includes Paulo Salim Maluf, former mayor of São Paulo and governor of São Paulo state, who is currently in prison on charges of embezzlement.)

One highly visible, nationwide company with no real Arab connections, although many Brazilians mistakenly think otherwise, is the popular fast-food restaurant chain Habib’s, which serves Arab-style esfihas and other traditional cuisine at more than 260 franchises across Brazil.

|

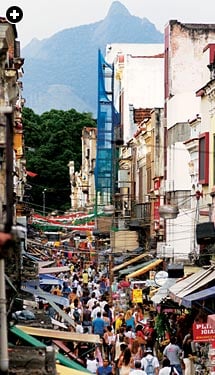

An outdoor market runs through the heart of downtown Rio de Janeiro's Sahara district, settled by Arab immigrants. |

o be sure, the Arabs were hardly the only immigrants to discover Brazil. Millions of Portuguese, Germans, Italians, Spaniards and Japanese also settled here in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, more Japanese live in São Paulo than in any other non-Japanese city in the world.

o be sure, the Arabs were hardly the only immigrants to discover Brazil. Millions of Portuguese, Germans, Italians, Spaniards and Japanese also settled here in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, more Japanese live in São Paulo than in any other non-Japanese city in the world.

Yet unlike the Japanese-dominated São Paulo neighborhood of Liberdade, with Japanese shops and restaurants and Japanese-language street signs, the closest thing to an “Arab neighborhood” is the lively Sahara district of Rio de Janeiro, which is home to many Arab-owned shops, groceries and a famous open-air market.

Rio is also home to Brazil’s ambassador to the United States, Roberto Pinto Ferreira Abdenur, whose father was from the Lebanese town of Hamdun. (His mother’s family came from Portugal.) He grew up in the days when the spectacular beachfront city was still Brazil’s capital, and at 21 he joined the foreign service, beginning a string of overseas assignments that has included ambassadorial posts to Ecuador, China, Germany and Austria before he presented his credentials in Washington in April 2004.

“I am a career diplomat with no political affiliation,” Abdenur says. “Our foreign ministry was never politicized, even during the military dictatorship. I am not a member of any political party and never will be.”

Nevertheless, Abdenur, 64, makes no secret of his admiration for the policies of President Lula. Though elected in 2002 on a platform of protectionism, worker rights and anti-globalization, Lula has since focused more on boosting Brazil’s export-driven economy.

“Brazil is deeply committed to opening its borders and becoming more engaged in world trade,” says Abdenur. “Although Brazil is one of the 10 biggest economies in the world, we have only one percent of world exports, which is ridiculously low.”

To that end, in December 2003 Lula toured Syria, Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Libya, becoming the first Brazilian head of state to visit the Middle East since emperor Dom Pedro II traveled the region in the 1870’s.

That trip led to this year’s unprecedented summit in Brasília, co-hosted by Lula and Algerian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika. Never before had so many Arab and Latin American heads of state gathered in one room, all aiming to strengthen an interregional political and economic bond that many say has been long overdue for attention.

The summit proved good for business: Over the 12-month period ending in August, Brazilian exports to the 22 member states of the Arab League climbed by 25 percent to $4.7 billion, and imports jumped 49 percent to almost $5.2 billion. This translates into annualized regional trade of nearly $10 billion.

“For years, we have talked of the potential of the Arab market, and it is satisfying to see that the numbers show this reality,” says the current president of the CCAB, Antônio Sarkis, Jr.

Yet retailer Faisal Hammoud says great challenges lie ahead for Brazil. “It’s not easy, because the Arab world has a lot of money to spend and countries much more competitive than Brazil are also aiming for this market,” says the entrepreneur. “They want the best, and Brazil cannot compete in quality. But for cheaper goods, Brazil can compete, even against China.”

At present, Brazilian companies that have invested in the Middle East range from state oil giant Petrobras, which recently signed a contract to drill for petroleum in Libya, to furniture manufacturer Americanflex, based in Ribeirão Preto, which has opened a showroom in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates. Poultry giant Doux Frangosul, based in Porto Alegre, ships 40 percent of its monthly chicken exports to the Arab world, about 15,000 tons. Rio de Janeiro–based jewelry retailer H. Stern, with more than 160 outlets throughout Latin America, the United States and Europe, recently opened franchises in Dubai and Bahrain. O Boticário, a company that makes perfumes and cosmetics in the southern city of São José dos Pinhais, just inaugurated its first outlet in Egypt. (It already has one store and 30 points of sale in Saudi Arabia, as well as 20 points of sale in the United Arab Emirates and 60 in Jordan.)

Going in the other direction, Saudi entrepreneur Omar al-Idrisi wants to open up a foreign-trade brokerage in Brazil, something that will really take off, he says, once UAE-based Emirates Airlines inaugurates nonstop service between Dubai and São Paulo near the end of this year.

And perhaps most significant, the Arab League in September approved the opening of an office in Brasília.

“We have been thinking of promoting regular business meetings, like the one held in São Paulo soon after the May summit,” al-Idrisi said in a press release. “We would like this kind of event to repeat itself, alternating between an Arab and a South American city. We also support all initiatives towards opening air links between the two regions.”

“Trade is something you do when the opportunity is there and the price is good. It’s the first level of a relationship,” says Atallah. “Now we have to move to the second level. We want the Arabs to know more about Brazil, and we want Brazilians to know more about the Arab world.”

|

Larry Luxner (www.luxner.com) is a free-lance journalist and publisher of the business newsletter CubaNews in Washington, D.C. |

|

Douglas Engle (www.douglasengle.com) is a free-lance photographer based in Rio de Janeiro. |