|

|

|

|

|

|

Old Sana‘a also contains an estimated 6000 “tower houses” of four to nine stories. Parts of some date to the 11th century and earlier, and the style is unique in the Arabian Peninsula. The lower floors of tower houses are traditionally used for storage, while upper floors are for cooking and family life. On the top floor of many is a social room, known

as a mafraj, whose windows overlook the city.

TOP AND CENTER LEFT: WILLIAM TRACY |

In mid-February 1978, on my first morning in Sana‘a, I woke up before first light. Illuminated by the flame of a single bedside candle, the undulating overhead ceiling beams, plastered in white gypsum, meandered in slow, graceful curves, blending into the plastered walls as though the room had been carved from a single block of white chalk. The interplay of shadows on stark white surfaces made it impossible to distinguish where architecture ended and sculpture began. As in most traditional Yemeni architecture, there were few straight lines, flat surfaces or square corners. The overall feel of the space was harmonious, intimate, functional and cozy. It was an ideal room.

dressed and ascended the rough-hewn stone staircase to the flat rooftop so I could watch my first sunrise over the city. From there I could only distinguish random pinpoints of light and the vague rectangular shapes of surrounding buildings as the morning call to prayer drifted back and forth across the still-sleeping city. A soft morning light began to penetrate the deep, darkened lanes; shadows became noticeable, and I caught my breath as the jumble of towering, earth-colored buildings became visible. I looked out at an architectural wonder, a gingerbread fantasy in which every surface appeared to be adorned with mad geometric designs, covered in squiggles of white cake icing. Each façade seemed to blend into the next, and the thousands of whitewashed, irregular window frames, the low-relief zigzag friezes and the openwork in the stone and brick walls appeared to be one solid construction.

dressed and ascended the rough-hewn stone staircase to the flat rooftop so I could watch my first sunrise over the city. From there I could only distinguish random pinpoints of light and the vague rectangular shapes of surrounding buildings as the morning call to prayer drifted back and forth across the still-sleeping city. A soft morning light began to penetrate the deep, darkened lanes; shadows became noticeable, and I caught my breath as the jumble of towering, earth-colored buildings became visible. I looked out at an architectural wonder, a gingerbread fantasy in which every surface appeared to be adorned with mad geometric designs, covered in squiggles of white cake icing. Each façade seemed to blend into the next, and the thousands of whitewashed, irregular window frames, the low-relief zigzag friezes and the openwork in the stone and brick walls appeared to be one solid construction.

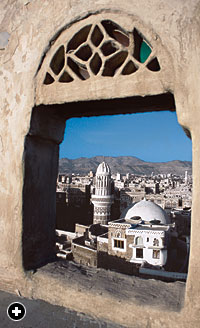

Nearby, I saw delicate gypsum tracery framing brilliantly colored stained-glass fanlights, while in the distance white minarets thrust above the skyline to bathe in the first pinkish glow of dawn. As households began to stir, black swallows darted over the rooftops, and ghostly white clouds of smoke from breakfast fires drifted through the maze of buildings. The smell of burning wood and charcoal permeated the crisp morning air, and deep in the twisting passageways, dark figures moved slowly.

|

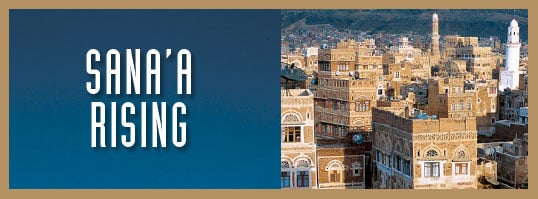

Above: Set on a plateau at 2300 meters (7360'), Sana‘a is the capital of Yemen. Its old city center is still home to roughly one-fifth of its metropolitan residents.

WILLIAM TRACY

Below: Inside of a "tower house" in Old Sana'a. |

|

Sana‘a had a unified look, but I was uncertain why this should be, because closer observation revealed more chaos than order. The buildings and their façades were similar, yet each was unique in its range of structural and decorative elements. On the façade of a nearby building, I counted 23 windows, only three vaguely alike. The others were so irregular in their proportions and shapes, and seemed placed in such a random fashion, that it was impossible to determine their precise function, let alone establish where one floor ended and the next one began. The millions of mud bricks and hand-cut stones the buildings were made of appeared to be the result of child’s play. Unique, handmade and dream-like in its execution, the architecture of Sana‘a presented itself as a spectacular living monument to the spontaneous genius of the Yemeni builders.

Like many first-time visitors to Sana‘a, I was left wondering how this city had come into being. Was it the result of intentional design, individual whim, happenstance—or all three? I am still not certain, and that is probably why the puzzle has remained lodged in my mind. I have returned to the old city of Sana‘a dozens of times over the last 27 years, and on my most recent visit, I spent the better part of a month within the old city walls, in hopes of understanding the origins of the architectural style that gives Sana‘a its “look.” I also wanted to know what was being done to preserve the old city, and I was curious to see how modern development was affecting the architectural heritage and the traditional social fabric of the old city.

It is said that Yemen is a country of warriors, poets and builders, but the most enduring impression of the country is likely the legacy of the builders, for Sana‘a is, quite simply, one of the world’s most beautiful cities. Situated at 2300 meters (7360') on a fertile plain surrounded by mountains, Sana‘a is more than 2500 years old. Since the first century BC, it has been a crossroads of overland and sea trade, a central link between Far Eastern and Chinese markets and those of the Mediterranean. The frankincense and myrrh trade flowed through Sana‘a on its way north, and the city was an important stop between the Red Sea and the ancient city of Ma’rib. Strategically situated at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula, where the Indian Ocean meets the Red Sea, ruggedly mountainous Yemen, with Sana‘a as its capital, is considered by many to be the ancestral heartland of Arab culture.

|

Above: More "tower houses" in Old Sana'a.

Below: Suspended on a seat called an isqalah ("cradle"), a crafstman applies gos, a white gypsum slurry, around windows. |

|

Closed to foreigners for nearly two centuries, Yemen was little known to the outside world until the mid-20th century. In 1970, the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini visited Sana‘a for a few days and later, in a radio interview, declared Yemen “the most beautiful country in the world,” and Sana‘a “a Venice built on sand.” He produced a 15-minute documentary, The Walls of Sana‘a, which he sent to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as an appeal for international help to save the old city. It has survived flash floods, earthquakes, massacres, repeated looting by tribesmen, civil wars and even, in 1991, Scud missile attacks. The city’s architecture has been demolished, damaged and rebuilt innumerable times, but in every instance, Sana‘a has risen from the debris and survived.

According to Ronald Lewcock, co-author of Sana‘a: An Arabian Islamic City and a distinguished scholar of the architecture of the Arabian Peninsula, the old city of Sana‘a has 106 mosques (several dating to the seventh century), 12 hammams (public bathhouses), dozens of suqs (specialized marketplaces), samsaras (market warehouses), palaces and gardens, and more than 6000 traditional tower houses, which average between five and eight stories in height and pre-date the 11th century. The origins of Sana‘a’s vernacular architecture are unclear, but, according to historical accounts, the style of building was already well established by the 10th century, as documented by Ibn Rustah, who wrote about “houses adorned with gypsum, baked bricks and symmetrical stones.”

Following the defeat and departure of the occupying army of the Ottoman Turks in 1630, Sana‘a became the capital of a hereditary line of rulers, and significant parts of surviving Sanani architecture date from that era. Roughly defined by the northern entrance of Bab (“Doorway” or “Gate”) Shu’ub in the north, Bab al-Salam to the southeast, Bab al-Yemen to the south and Bab al-Sabah to the west, the heart of the old city is contained within an area that measures approximately 1000 by 1500 meters (.62 by .93 mi). It is partially enclosed by eroding walls of zabur: coursed, beaten clay mixed with sand and straw chaff. A seasonal waterbed, Wadi Sa’ilah, runs through the old city near its western edge.

|

The old city is still entered through its four main gates.

ILENE PERLMAN

|

Even today, despite the surrounding urban sprawl, the old city of Sana‘a remains remarkably intact. In many ways it is still a vibrant and functioning medieval-modern Islamic city. According to legend, it was founded by Ham, the son of Noah, and some local sources claim that the Prophet’s brother was buried in the city. The Yemeni people were early converts to Islam in the seventh century, and there is ample evidence to indicate that Sana‘a was a center for the study and spread of Islam during the new religion’s first centuries.

As with any city, life in Sana‘a is in a perpetual state of change. Today, even cursory walks through the old city reveal striking juxtapositions of its past and the present. A short distance from where I saw a blindfolded camel plodding in a circle as it turned the millstone of a sesame-seed-oil press in a darkened basement, I found an Internet café on the ground floor of a 500-year-old tower house. Inside, tribesmen wearing jambiahs—ceremonial tribal daggers—were seated next to young students dressed in western-style clothing: All were surfing the Web and checking email. Across the street, blacksmiths were hand-forging stone-cutting chisels from the recycled drive-shafts of automobiles and trucks. Farther on, veiled women carried television sets and baskets of green onions balanced on their heads while workmen, seated on isqalah (precarious rope slings with wooden slats) five stories above the street, installed a circular piece of hand-cut alabaster in a window frame.

The traditional tower houses in the old city are set on stone foundations of basalt, upon which are built carefully fitted walls of locally quarried, chiseled tuffa and limestone five to 10 meters high (16–32'). Above that, the walls are made of ochre-colored fired rectangular bricks or coursed clay. A specially formulated, chalky white, aged lime plaster called qadad is applied as an exterior waterproofing layer to the flat rooftops. A white gypsum slurry called gos is used around the windows, on interior walls and as a decorative highlight on low-relief architectural features. Inside, the lower floors of tower houses are for storage, while upper floors are used for cooking and as family rooms, bedrooms and living areas. On the top of most traditional tower houses is the mafraj, a room with wide windows overlooking the city, the preferred place to socialize with friends and family in the afternoon and early evening.

|

A mason lays paving stones in one of the city's lanes, originally built to the width of two loaded camels. |

The lanes of the old city were built wide enough for two loaded camels to pass each other. Until the late 1960’s, there was little electrical wiring or indoor plumbing. Water was collected in buckets from shallow, hand-dug household wells or from larger community wells powered by donkeys or camels. With the increased demand for water for agricultural and domestic use, however, the water table had dropped so far by the mid-1980’s that pumps became essential. Solid-waste disposal systems originally used little water because they consisted of open-air catchment areas at the bottom of qadad-plastered vertical shafts and recesses (the mantal, or “long drop”) built into the exterior walls of the tower houses.

Many aspects of daily life in Sana‘a changed radically after a seven-year civil war ended in 1969. By the early 1970’s, thousands of Yemeni expatriate workers returned to Sana‘a from Saudi Arabia, Europe and the United States with their savings, and they started to change the appearance of the old city. According to Lewcock, in the five years from 1978 to 1982, Sana‘a’s population nearly quintupled, from 55,000 to more than 250,000. Ever since, uncoordinated and uncontrolled modernization efforts have been the primary threat to the future of the city’s architectural heritage.

|

Small business continues to dominate economic life in the old city.

Below: A juice vendor and a bakery. |

|

Water pipes were attached to exterior walls and flush toilets were installed with little thought about the effects of drainage or wastewater runoff; as a result, the foundations and walls of the old buildings began to be undermined. Estimates vary, but by the early 1980’s it became clear that nearly a third of the 6000 tower houses in the old city were urgently in need of repair because of water seepage. Satellite dishes appeared on rooftops, along with huge metal water tanks. Aluminum window frames replaced traditional wooden frames, and the use of reinforced concrete and concrete blocks created eyesores. Inadequate sanitation, poor phone service and limited schools, health services and recreational opportunities, as well as a shortage of master craftsmen to make repairs, all contributed to an exodus from the old city to new nearby suburbs. During this time, Marco Livadiotti, an Italian resident of Sana‘a for most of his life and the cultural heritage advisor to Yemen’s Ministry of Culture, estimated that 40 percent of historic Sana‘a was either gone or in immediate danger. Estimates of what has already been lost vary greatly, but it is documented that in 1978 and 1979, nearly three dozen tower houses collapsed due to water damage or lack of preventive maintenance by absentee owners.

Part of the deterioration was due to the departure of wealthy families moving out in search of more modern homes and public services. Replacing them were working-class families moving into Sana‘a from the countryside and surrounding villages. The result was a typical inner-city dilemma: A shrinking tax base was increasingly insufficient to cope with a historic city desperately in need of immediate—and expensive—restoration. At the time of my 1978 visit, many mosque gardens were overgrown with prickly pear and littered with trash; public squares were often cluttered with abandoned cars.

|

These chisels, made from recycled driveshafts of automobiles and trucks, will be put to use by the city's stonecutters. |

In 1984, UNESCO listed the old city as a World Heritage Site, and a conservation plan was put together with the local participation of the General Organization for the Protection of the Historical Cities of Yemen, The General Organization for Antiquities and Museums, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Tourism and Environment, the citizens of Sana‘a, master Yemeni builders and tradesmen, the World Bank, foreign investors and numerous other organizations. Early on, the main goals were to inventory historic buildings, save what was left of them, and devise ways to monitor conservation and breathe new economic and social life into the city. This ambitious undertaking was complicated by the desire to upgrade the city’s drinking water, septic sewers, storm sewers and street paving—all without compromising Sana‘a’s “look” or its traditional way of life. The overarching idea was to promote a vital, living city, rather than an open-air architectural museum. Partly due to the early success of these efforts, the city won an Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1995 “for having successfully incorporated the efforts of the public and private sectors, local and foreign bodies, and individuals and groups in protection of one of the jewels of Muslim architectural and urban heritage.”

To evaluate the successes and shortcomings of work on the old city over the last 30 years, I turned to ‘Abd al-Rahman Muhammad al-Haddad, a civil engineer from the Ministry of Public Works with more than 18 years of experience on structural reports and architectural surveys, restorations of mosques and mosque gardens (see page 34), and street-paving programs. Brought up in a well-respected local family of Qur’anic scholars, al-Haddad had an intimate knowledge of how the city worked.

|

Interior of a traditional tower house diwan, or sitting room. |

For three weeks, starting shortly after dawn each day, we traversed the city’s meandering lanes, visiting palaces, abandoned historic buildings, public-works projects, new-construction sites, ruins, commercial and domestic restorations in progress, well diggings, master craftsmen at their tasks, open-air markets, mosques, minarets, hammams, gardens and innumerable private homes. The simple mention of his family name opened every door we knocked upon.

Al-Haddad explained that much progress was being made, but the main difficulties had to do with the enforcement of conservation and maintenance regulations on an independent-minded population of city dwellers, many of whom had little interest in, or appreciation of, the purpose of protecting the old city. Understandably, many property owners complained of the financial burdens of such regulations.

“We want to save what is left for future generations,” al-Haddad told me. “And this is not easy unless we find a way to monitor all aspects of preservation and conservation. Just like people in your country, people want to be modern and drive their cars everywhere and have modern bathrooms and electricity. Tower houses were designed for large extended families, and now many parents want to just live with their children. It is very difficult to change the family use of tower houses or to incorporate modern services and conveniences in a city like Sana‘a. How to improve the city without destroying it is our problem.”

|

Above: An unglazed window frames a view of the old city and beyond.

Below: Lit from inside, traditional stained-glass windows add evening sparkle to the city that, in the ninth century, Ahmad 'Isa al-Rada'i called "Sana'a of the mansions and towers tall / High in antiquity, from time afore / Proud in resisting covetous assault. |

|

But I could clearly see that positive and enduring changes had been made. Nearly all of the streets have been paved in stone. Vehicle traffic is controlled with barriers, limited-access hours for commercial deliveries and restricted parking. Public toilets have been rebuilt, and nearly everywhere craftsmen are at work making repairs. The streets are swept regularly and garbage is collected. Renovations are under way on buildings from private homes to the Great Mosque. The façades of the tower houses are regularly recoated with gypsum. Even the old mud walls that once surrounded the old city are being rebuilt. Mosque gardens are once again being used to grow vegetables. Unlicensed buildings have been removed or altered to conform to traditional design standards, using traditional materials and building techniques.

But just outside the old city, major work remains to be done. Both the historic Turkish residential and garden quarter, Bir al-Azab, and the Jewish, Christian and Persian neighborhood of al-Qaa‘ lie neglected by the conservation efforts because, as Livadiotti explains, they lie just outside the boundaries of the old city walls. “These neighborhoods are an essential part of old Sana‘a,” he said, but at this time “there is no money to preserve them—and little interest.”

In many respects, the old city of Sana‘a is still struggling to strike a balance between old and new. But it was clear, from my discussions with al-Haddad and my conversations with dozens of residents, that this can only be achieved through the enthusiastic participation of the people who live there. Based on the progress that al-Haddad showed me, and the positive mood of so many people, I realized that, despite the many setbacks, the old city was alive and well, even flourishing. Once again, I left Sana‘a as I had so many times before: with a keen desire to return.

|

Eric Hansen (ekhansen@ix.netcom.com) is the author of Motoring with Mohammed – Journeys to Yemen and the Red Sea (Vintage Departures).He has worked as a photojournalist in Yemen over the past three decades and is a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World. |