Written by Tim Mackintosh-Smith

he scent of basil is the first thing I notice when I wake on Fridays, then the hum of voices from below the window.

he scent of basil is the first thing I notice when I wake on Fridays, then the hum of voices from below the window.

Down on al-Zumur, one of the busiest market streets in the old city of Sana‘a, my neighbor Maryam the qashshamah sits behind a heap of greenery: deep green alfalfa, fodder for animals; gray-green ‘ansif (Astragalus abyssinicus) to give a zing to tea or to shafut, sorghum pancakes drenched in herby yogurt; parsley, rocket and fennel; and chives, lettuce and mint. The green is punctuated by giant white radishes, orange-yellow marigolds, and the bruise-purple of that pungent basil. Other colors come and go with the seasons, like those of quinces, figs and—best but briefest of all—the bloomy black of mulberries. All this I must climb over to get to my favorite breakfast place along the road, for Maryam’s shop is my doorstep. But the pile of vegetation—usually interspersed with small children—is a pleasing inconvenience. And in any case Maryam always disarms potential objections. “Here,” she says, holding out a bunch of basil and marigolds, “have a mushquri.”

You will look in vain for that word in the standard Arabic reference books. Its origin goes back further—to Sabaic, one of the ancient South Arabian languages. Shqr (the vowels are anyone’s guess) is the cresting on a building, and 2000 years of semantic vagaries have turned it to mean a posy to decorate your turban—a crest for the head. Similarly, qashshamah, Maryam’s job title, and that of her male equivalent, the qashsham, as well as miqshamah (plural: maqaashim), the garden where they grow their produce, all have an origin just as old but better preserved: qshmt, the Sabaic

You will look in vain for that word in the standard Arabic reference books. Its origin goes back further—to Sabaic, one of the ancient South Arabian languages. Shqr (the vowels are anyone’s guess) is the cresting on a building, and 2000 years of semantic vagaries have turned it to mean a posy to decorate your turban—a crest for the head. Similarly, qashshamah, Maryam’s job title, and that of her male equivalent, the qashsham, as well as miqshamah (plural: maqaashim), the garden where they grow their produce, all have an origin just as old but better preserved: qshmt, the Sabaic

word for a vegetable plot.

In this long cultivated and most fertile corner of Arabia, the Qur’anic “Land of the Two Gardens,” it is hardly surprising that the roots of words that have to do with growing things go deep. What is remarkable, in the intensely urban setting of Sana‘a—a walled metropolis crowded with towers today, and the place where the Sabaeans built the 10-story Palace of Ghumdan some two millennia ago—is that not only the words survive: So, too, do the gardens. My Friday marigolds were picked less than a minute’s walk from Maryam’s doorstep shop.

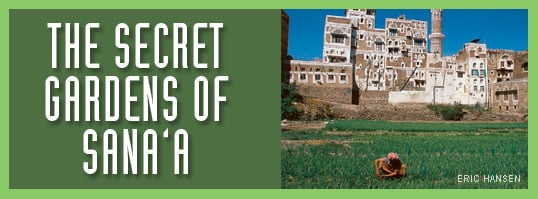

The Italian writer Alberto Moravia once described Sana‘a as a “Venice of dust.” Since his visit, the streets have been paved with stone, and the dust is less in evidence. But the first impression is still one of sun-dried palazzos, of deep-cut streets flowing with people but devoid of moisture and vegetation. Amid this, it’s easy to overlook the quiet spaces in between. And that is the only way most of the city’s gardens can be seen at all: by overlooking them. Climb to the fifth floor of my house, and two gardens reveal themselves. To the east is Maryam’s, the miqshamah of Khudayr Mosque, a rectangle of green—mostly chives (bay’ah), the dominant garden crop—subdivided by little banks of raised earth. To the west, there is Bustan Na’man. Go up another couple of floors, and the tops of what are locally called “pepper trees” mark the edges of other gardens, otherwise unseen. A bit more than a stone’s throw to the south, there is another miqshamah, totally concealed behind a curtain wall of tower houses: I didn’t even know it was there until I began to write this and looked at the map. Other great Islamic cities, such as Damascus and Bukhara, are famous for the gardens that surround them, but in Sana‘a, they are all on the inside, walled gardens wrapped in a walled city, doubly hidden.

The Italian writer Alberto Moravia once described Sana‘a as a “Venice of dust.” Since his visit, the streets have been paved with stone, and the dust is less in evidence. But the first impression is still one of sun-dried palazzos, of deep-cut streets flowing with people but devoid of moisture and vegetation. Amid this, it’s easy to overlook the quiet spaces in between. And that is the only way most of the city’s gardens can be seen at all: by overlooking them. Climb to the fifth floor of my house, and two gardens reveal themselves. To the east is Maryam’s, the miqshamah of Khudayr Mosque, a rectangle of green—mostly chives (bay’ah), the dominant garden crop—subdivided by little banks of raised earth. To the west, there is Bustan Na’man. Go up another couple of floors, and the tops of what are locally called “pepper trees” mark the edges of other gardens, otherwise unseen. A bit more than a stone’s throw to the south, there is another miqshamah, totally concealed behind a curtain wall of tower houses: I didn’t even know it was there until I began to write this and looked at the map. Other great Islamic cities, such as Damascus and Bukhara, are famous for the gardens that surround them, but in Sana‘a, they are all on the inside, walled gardens wrapped in a walled city, doubly hidden.

Altogether there are 43 of them. They range in area from nearly three hectares (7.4 acres) down to less than 1000 square meters (10,500 sq ft), all within the ring of mud wall and bastions that protects the historic core of Sana‘a. Only a handful are visible at all from street level, and of these, one alone, Miqshamat al-Qasimi, can be seen in its entirety. The unsuspecting visitor would never guess that these urban oases occupy 13 percent of the space within the city wall. Most of them bear that ancient name, miqshamah, and most are also attached to nearby mosques as waqf, property of a foundation and inalienable under Islamic law. A few, known by the more usual Arabic name bustan, are held by individual families. None are public parks (except for the fortunate eyes of neighboring householders). Whether stadium- or backyard-sized, miqshamah or bustan, they were all founded as working market gardens.

The gardens may be largely invisible, but until a couple of generations ago they were highly audible. For the British entomologist Hugh Scott, visiting Sana‘a in the 1930’s, the characteristic sound of the city was a continual high-pitched screeching like the noise of gulls. Caused by the friction of wooden pulleys, this was the accompaniment to a more harmonious noise, the songs of the well-men. One went:

Hear me, oh you who come up from the well—

A candle for the lass and a lamp for the lad!

Hear me, oh bird, oh ash-grey bird—

Spread your wings and fly me home!

To the plaintive backing track of the pulleys and the voices of their drivers, camels or donkeys trudged up an inclined ramp to the lip of the well, then down again, gravity helping them draw up brimming leather buckets, which the well-men tipped into a cistern at the top of the incline. The length of these ramps, called in Sana‘a marani’ (singular: mirna’), was dictated by the depth of the well—usually between 40 and 70 meters (130'–225'). From the wellhead, the water passed into the garden either directly or, in the case of gardens attached to mosques, via the ablution cubicles provided for worshipers.

|

ERIC HANSEN |

“It flows like a stream,” wrote al-Shahari in his mid-18th-century Description of Sana‘a, “since the least of the wells is provided with three or four sets of pulleys, and these work constantly, night and day.” The miqshamah of the Great Mosque, he adds, had two wells, each with eight sets of pulleys. Nothing was wasted—neither time, nor the spent ablution water, nor runoff from the streets in times of rain, which was also channeled into the gardens. The dung of the animals, supplemented with ash from nearby public baths (themselves fueled by dried excreta collected from the lavatories of neighboring houses), went to fertilize the gardens. Even space was recycled. One mirna’, that of Ibn al-Husayn, was tunneled under the courtyard of its mosque, while another, at Miqshamat Talhah, was given a superstructure of hostel rooms for itinerant scholars.

By custom, the head qashsham of each mosque-garden is in charge of providing water for ablutions and keeping the ablution block clean. Gardeners of family-owned bustans work as sharecroppers, dividing the income with the beneficiaries. But those who benefit most of all are the citizens of Sana‘a. Not only are food, fodder and Friday-best headgear to be had, sometimes literally, on their doorsteps, but so too are plants used in the age-old rites of passage. Rue, for example, decorates the scenes of birth- and wedding-parties; basil adorns not only the heads of the living, but also the biers of the dead. Medicinal plants can sometimes be found in the maqaashim, but these are not for sale—they are given in exchange for a prayer for the gardener’s health. (I once endured a course of liquidized mirrar [Ononis antiquorum], prescribed for a bout of jaundice. It is also known in Sana‘a as qubbab. Both words mean “very bitter”—an understatement.)

From birth to death, in sickness and in health, the people of Sana‘a rely on its hidden gardens for many of their needs. It seems unfair, therefore, that the gardeners have traditionally been consigned to the bottom rungs of the city’s social ladder. (The reason is unclear, but may be connected to their dealings with used ablution water.) “It’s better to be a qashsham in Sana‘a,” an old proverb goes, “than a shaykh in the sticks.” The saying is double-edged: Even the noblest countryman, it implies, is worse off than the lowliest city dweller. All the same, qashshams are actually treated with respect. For example, from time to time, when the municipal authorities crack down on unlicensed street traders, my street, al-Zumur, empties. And Maryam looks on, secure in her doorstep greengrocery. No one would dream of asking her to move. She is as much a part of the city’s fabric as the gardens themselves.

I began to wonder how these maqaashim and bustans had become so inseparably stitched into Sana‘a’s urban patchwork. The gardeners didn’t know. The ones I asked answered with a shrug, or said they’d always been there. And not only the city’s visitors, but also most of its historians seem to overlook the gardens. But I did come across one passage that appeared to solve the mystery. Formerly, wrote Qadi Muhammad al-Hajari in his 1942 book Mosques of Sana‘a, the city’s places of prayer “were for the most part lacking in ablution facilities, cisterns and wells.”

Worshipers would make their ablutions at home [he wrote], then go to the mosque to perform the appointed prayers. Then, in the year 933 [AD 1526–1527], during the government of Imam al-Mutawakkil ‘ala ‘llah Sharaf al-Din Yahya,…a plague befell Sana‘a. As a result, much property was left abandoned, for there was no one to inherit it. The Imam therefore—may God have mercy on him—directed that these estates be used for the benefit of the mosques, assigning the property to selected mosques in each quarter of the city. He gave orders for the digging of wells and the construction of cisterns, ablution blocks and associated structures. He also appointed guardians, imams and muezzins for these mosques, together with well-men whose duty it was to draw the water for the ablution blocks. This they would do every day, irrigating their gardens with the spent water and replacing it with fresh supplies for the worshipers. The practice became established and has continued in more recent times, up to the present.

In the long history of Sana‘a, the 500 years since Imam Sharaf al-Din turned a disaster into an urban amenity is no great span; I suspected that the origins of its gardens were still older. For one thing, it seemed more than likely that the gardens that became waqf property would already have been open space. Besides, the survival of that pre-Arabic term, miqshamah, suggested a continuous tradition from far earlier times. Another passage in al-Hajari’s book took the association of mosque and garden back three centuries more: In AH 603 (AD 1206–1207), it said, quoting an inscription in the Great Mosque, an officer of the short-lived Ayyubid Dynasty established a garden and well by the musalla, the open-air mosque to the north of the city, where citizens prayed at the time of the two major ‘ids, or festivals. I found an account by a contemporary chronicler that gave more details: A high mud wall enclosing an expanse of flowers and fruit trees; a well, a cistern and water channels lined with qadad, an indigenous concrete made from lime and powdered volcanic stone; a resident gardener to work the well. A typical miqshamah—except that it was outside the city wall. It was only later, as I looked through al-Razi’s 11th-century history of the city (to which the account of the musalla garden forms an appendix), that I realized that the nexus of mosque and garden may be as old, and as literally central to Sana‘a, as can be.

Whatever else they differ over, all historians of Sana‘a, from al-Razi onward, agree on one point: that the city’s first mosque was built by order of the Prophet Muhammad in the garden beside the Palace of Ghumdan, the high-rise hub of the ancient city. The mosque—the Great Mosque—is still there, one of the oldest places of prayer in the Islamic world. Ghumdan itself was demolished later in the seventh century, but it is tempting to wonder whether part of the old palace garden might have survived, next to the mosque.

An intriguing but equivocal bit of evidence exists—the illuminated frontispiece of a copy of the Qur’an that was discovered tucked away in the ceiling of the mosque 30 years ago. There is little doubt that this Qur’an was copied early in the eighth century in Damascus, capital of what was then the Umayyad Caliphate, and sent to Sana‘a, then also under Umayyad rule. The frontispiece shows two magnificent and densely detailed mosques. Just beyond their Makkah-facing walls are gardens filled with fruit trees and leafy plants. Are they reflections of Paradise? Or are they depictions of an extant, earthly garden next to the mosque in Sana‘a? Whatever the answer, the site of the mosque was still rich in allusions to an otherworldly beauty for the poet-historian al-Hamdani, writing two centuries on: “And if God made on Earth a heaven for our eyes / Then Ghumdan’s palace was by that earthly paradise.”

Earthly paradises need water. In Sana‘a it seemed to be a never-failing blessing. Ghumdan’s channels, said al-Hamdani, “gurgled ceaselessly,” and these pleasant sounds flowed down the ages, and increased. “Sana‘a’s groundwater has risen so enormously,” observed al-Shahari in 1757–1758, “that it has reached almost halfway up the wells…. Streams have sprung forth, and there are some 20 of them around the city.” Earthly paradises proliferated: 50 years later, the poet ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Anisi wrote of Jabal Nuqum, the mountain that flanks Sana‘a to the east, as surveying a city of “lofty palaces crowned with gleaming belvederes / White among the green of gardens.”

|

Showing greenery both outside the mosque wall (at top) and inside its courtyard (bottom), this gragment of an early eigth-century parchment Qur'an-one of the earliest known-helps document the close relationship of mosques and gardens. Though found in Sana', historians believe this fragment was probably produced in the Umayyad court of Damascus.

THE HOUSE OF MANUSCRIPTS, SANA'A/URSULA DREIBHOLZ & HANS-CASPER GRAF VON BOTHMER |

The first detailed map of Sana‘a, drawn and colored by the Italian traveler Renzo Manzoni in 1879, shows an astonishing amount of green—around a quarter of the original city’s area, and no less than three-quarters of Bir al-Azab, the garden suburb that had sprouted to the west over the preceding 300 years. Within living memory, most Sana‘a households drew their water from their own wells. And then the population ballooned—from little more than 70,000 to over a million in the last 50 years. A rash of boreholes spread uncontrolled across the surrounding plain, and today every one of those domestic wells is dry. In the gardens, the song of the well ramps has given way to the thump of pumps, sucking precious water from ever-deeper strata.

If, that is, the gardeners are lucky. “It’s in God’s hands,” the owner of the well-drilling rig at Miqshamat al-Wushali said when I asked how far down he was going. “We might find something at 400 meters (1300').” I wasn’t surprised. Miqshamat Khudayr—Maryam’s garden—is home to a hole almost that deep, drilled at great expense and to little effect. Her rectangle of green is now dwarfed by a much bigger rectangle of dust, currently a popular soccer pitch. Photos of a generation ago, showing the men of the family against a wall of luxuriant green, look as though they were from another country. Around a quarter of Sana‘a’s gardens are now abandoned, and some are probably lost for good. Bustan ‘Inqad, for instance, is now Suq ‘Inqad—a marketplace for the sale of vegetables, no longer a field in which to grow them. Outside the city wall, a school is being built on the last remaining bit of that 13th-century garden by the old musalla. Jabal Nuqum now surveys a city where the green is disappearing—an island city lapped by a gray suburban sea.

The news is not all bad. About three years ago, I peered over the high wall of Miqshamat Dawud, one of the partially visible gardens, and had a shock. A mechanical digger had punched a way in, channels and banks had been razed, and nearly all the vegetation had been ripped out. Only a few of the larger trees remained, looking like survivors of a war. But one of the worshipers from the Dawud Mosque explained to me that the miqshamah was not being destroyed, but restored.

‘Abd al-Rahman Muhammad al-Haddad, in charge of the restoration and himself a native of Dawud Quarter, later told me that 12,000 cubic meters (15,700 cu yd) of detritus were removed from the garden. When this had been done, retaining walls and earth banks were reconstructed and the miqshamah replanted. It is now conspicuously green in its frame of tawny walls and towering houses. So too are the six other gardens renovated so far in a program run by the Social Fund for Development (SFD), an organization that channels funding for agricultural, educational and other projects across Yemen. In collaboration with the General Office for the Preservation of Historic Cities in Yemen, they have earmarked seven more gardens for renovation. Of course, no amount of expertise or goodwill can reverse the inexorable fall of the water table, so the SFD engineers are paying special attention to managing the gardens’ dwindling lifeblood. And they have realized that the best material for repairing hydraulic structures also happens to be the oldest —qadad, that indigenous concrete. (It should give many years of service: I have seen a pre-Islamic cistern lined with the material that was still in use.)

And so some of Sana‘a’s secret gardens are coming back to life. And some are no longer so secret: Where possible, the restorers are inserting “windows” in the garden walls, barred openings that offer sudden glimpses of green.

Many, though, remain obstinately hidden. “What garden?” said a shopkeeper when I asked him how to get into the garden of the ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib Mosque. His shop backed on to it, but he didn’t know it was there. “Climb over that wall,” some small boys advised. Eventually I discovered a more dignified way in, through the courtyards of two private houses, and I found myself in a tangle of fig and “pepper” trees—a tiny but literal urban jungle, lost in the innards of the Suq.

Maryam’s garden is on the SFD ’s list for restoration, too. Meanwhile, she sits on my doorstep, surrounded by greenery —some of it, admittedly, brought in from far outside the city—and by plenty of children to carry on the tradition.

But one part of that tradition has gone for ever. At the other end of town, I was surprised to find a gang of masons chipping stones to rebuild the well ramp beside Qubbat al-Mahdi Mosque. One of the men laughed when I asked if the mirna’ was going back into operation. “To get to the water these days, we’d have to extend it out beyond the city wall, and the top of it would be as tall as a skyscraper! I think they’re going to put a statue on it—you know, of a qashsham and his camels. For the tourists.”

The song of the well-men, and the shriek of the straining pulleys, will never be heard again.

|

Tim Mackintosh-Smith (tim@yemen.net.ye) has made his home in Sana‘a for more than 20 years. His most recent book is The Hall of a Thousand Columns: Hindustan to Malabar with Ibn Battutah (John Murray). |