nother small group of men steps forward between the lines of singers and begins pounding out a majestically slow 6/8 rhythm in three parts on large frame drums. The men in the two lines, wearing long embroidered coats known as daghla over their white thawbs, bend at the knee and lean forward as they sing. Then they begin slowly lifting and lowering silver ceremonial swords in time to the stately rhythm.

nother small group of men steps forward between the lines of singers and begins pounding out a majestically slow 6/8 rhythm in three parts on large frame drums. The men in the two lines, wearing long embroidered coats known as daghla over their white thawbs, bend at the knee and lean forward as they sing. Then they begin slowly lifting and lowering silver ceremonial swords in time to the stately rhythm.

The ‘ardah is one of many Saudi folk-music traditions that Saudis refer to collectively as al-funun al-sha‘abiyyah, the folk arts, or more simply, al-fulklur, folklore. Varying by region, and again by town and city within each region, individual traditions are known as an art (fann) or type (lawn). Many combine song with drumming, clapping and group dancing. Performers wear regional costumes and sometimes dance with props, such as the sword in the ‘ardah or the bamboo cane in the Western Province’s mizmar.

To get the full sense of these arts, one has to see them as well as hear them. They are poetry, song, music, rhythm, dance and costume all rolled into one.

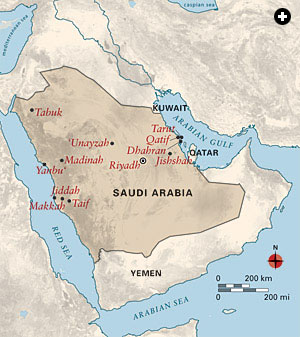

There are hundreds of folk-music and dance troupes all over Saudi Arabia, their members spanning sev- eral generations. Like the al-Jishshah Folklore Troupe in the Eastern Province, they focus on regional traditions that they perform for weddings and other special occasions. Al-Jishshah’s group specializes in several varieties of the ‘ardah, as well as the songs of their town and the al-Hasa Oasis.

Blending elegiac poetry with singing, drumming and majestically slow dance movements, the ‘ardah has become a symbol of traditional Saudi Arabian culture. While variations are also performed in other countries of the west- ern Arabian Gulf, experts point to the ‘ardah’s origins in the Arabian desert among the Bedouin.

It started out as a war dance used to get men ready for battle. “In the old days before the unification of the kingdom, the ‘ardah used to be called al-faza‘, or ‘fright.’ After unification, the dance became a dance of peace. It became known as al-‘ardah al-najdiyyah, since it is well known in Najd,” or central Saudi Arabia, explains Muhammad al-Maiman, president of the Committee for Heritage and Folk Arts at the Riyadh headquarters of the Saudi Society for Arts and Culture. The society consists of a kingdom-wide network of artists and folklore specialists. Membership is open to both men and women and includes painters, writers, scholars, playwrights, historians, actors and musicians.

“The ‘ardah tradition contains the national spirit,” al-Maiman continues. “The poems are about the country. Its movements are dignified, masculine and proud—and it’s an expression of history, too.” He explains that there is a plan to teach the ‘ardah to all schoolboys in the kingdom.

One can catch a glimpse of the ‘ardah in live Saudi Arabian television broadcasts of the kingdom’s folk-life festival at Janadriyah, held each year outside Riyadh. The festival opens with a rendition of an official ‘ardah, as well as a performance of other folk-music and dance styles that are part of a multimedia stage show called the Operette. “The king also goes to another place in Riyadh to do an ‘ardah so the general citizens can take part,” al-Maiman adds.

Each rendition of the ‘ardah, which might include as many as 50 lines of sung poetry, lasts up to half an hour. Then the singing swordsmen and drummers take a break before starting again. If a dancer gets tired during the song, he can rest his sword on his shoulders and continue stepping with the group. Though a large crowd often gathers to watch the ‘ardah, practicality limits the performance itself to about 90 participants: two lines of 40 swordsmen with 10 drummers on one end. “The drums sound like thunder,” al-Maiman says.

Just as Bedouin culture gave rise to the ‘ardah, other traditional ways of life that predated the modern era produced distinct folk-music styles across the kingdom. Specific Eastern Province folk arts derive from pearl-diving, seafaring, oasis agriculture and long-distance trade. There are date-harvest songs in al-Hasa, and shepherding songs from the Southwest and other regions.

Neighboring cultures add spice to Saudi folk-music styles, reflecting long years of contact between Arabia and Africa and the Levant, as well as the Indian subcontinent. The western seacoast town of Yanbu‘ is famous for the simsimiyah, a harp-like lyre that is also found in coastal areas of East Africa and Egypt. The surnai, a loud, double-reed wind instrument, and several types of African drums made their way into Saudi and Gulf music, brought by immigrants from India and Africa who settled along the Arab Gulf coast over the centuries.

Neighboring cultures add spice to Saudi folk-music styles, reflecting long years of contact between Arabia and Africa and the Levant, as well as the Indian subcontinent. The western seacoast town of Yanbu‘ is famous for the simsimiyah, a harp-like lyre that is also found in coastal areas of East Africa and Egypt. The surnai, a loud, double-reed wind instrument, and several types of African drums made their way into Saudi and Gulf music, brought by immigrants from India and Africa who settled along the Arab Gulf coast over the centuries.

Poetic lyrics drive these folk-music traditions. They praise the valor of heroic leaders and tell battle stories, explore religious themes, pine for the beauty and sweet character of the lost beloved, mourn the loss of family and friends, and offer encouragement to the bride and groom. Songs often mention well-known places, lending them an extra air of nostalgia.

A simple, repeated melody passed back and forth by a soloist and a chorus forms the core of most Saudi folk songs. In towns and cities, the melody is sometimes picked up by a small ensemble of instrumentalists, who might play the ‘ud (unfretted lute), the qanun (lap-plucked zither), the nay (reed flute) and the violin.

Even in the most rural traditions, nearly all melodies fall within the esthetic principles of the centuries-old maqam system that is a hallmark of Middle Eastern music. It describes a series of modes or scales, as well as a way of improvising and forming melodies within those modes. Though there is no harmony, harmonic intervals can sometimes be heard for a moment or two in passing.

Drums are an orchestra in themselves. Most Saudi and Gulf folk music makes use of shallow frame drums that are held in the left hand and struck with the right. They range in size from 15 to 65 centimeters (6–26") across. A single-sided frame drum is called a tar; a double-sided drum, a tabl. Groups decorate these drums to suit their needs, such as in the ‘ardah where colorful wool tassels and wooden handles are often added. Some folkloric troupes paint their names on their drums, along with traditional designs like the Saudi emblem of crossed swords and palm tree.

While a given rhythm might appear to be a simple 4/4 or 6/8 time on the surface, if you listen closely, you can hear a complex, multi-toned richness as the drums play off each other, in syncopation.

“I’ve spoken with many musicians in Europe and I tell them we have harmony in our percussion, in our drumming,” muses Tarek ‘Abd al-Hakim, who at 86 is the dean of Saudi folk-music experts. A legendary composer and musician, he has long advocated the study and preservation of Saudi folk arts. He penned the melody for the kingdom’s national anthem and is a former head of the Saudi Society for Arts and Culture.

“They have cellos, contrabasses and pianos doing the harmony, and violins doing the melody,” he continues. “We have the same thing with our drums. Each one plays a different line. It’s as if one is playing the melody and the others are playing harmony. In Taif, we have the folk-song style called majrur, with 12 tars playing, all of them small ones, all together.”

Saudi musicians add one more layer of percussive sound to their arts: resonant, rhythmic clapping known as tasfiq. Found in many parts of the Arab world, tasfiq usually occurs during drum or instrumental refrains between song verses. One or two clappers lead the rest through a frenzied round of clapping, marking out complex rhythmic patterns that might inspire participants to dance. Hands fly up and down, in and out, in a blur, until suddenly, cued by the leader, they all stop at once at the end of the phrase, just in time for the solo singer to start up again.

Dance movements seem to fall into two categories: steps done in unison, often in a line; and free-style movements done as solos or in pairs. In the majrur of Taif, the participants wear long, multicolored thawbs that whirl out as they dance and twirl while singing and playing the tar. In other folk songs in which everyone is seated or kneeling, an inspired participant might jump up and shake his shoulders during a round of tasfiq. Then he might run to the opposite end of the line and twirl in front of a friend, only to dive back to his place just as the clapping ends and the solo singer starts up again.

While these traditions are certainly colorful and lively, drawing young and old alike, Saudi youth are also tuned in to the global music scene. Like their peers all over the Middle East, young Saudis enjoy listening to pan-Arab and Gulf-style pop music that’s broadcast on satellite networks, like Saudi Arabia’s Rotana, and Arab networks like lbc and MBC. How can the old folk-music traditions survive when competing with the glitz of modern pop music in all its forms?

“The folk arts are alive and flourishing,” insists ‘Abd al-Hakim. “The young people are studying them in the evening. They love the folk songs. Why? If you have a wedding party, you have to have folk music and folk dance.” No matter how citified and worldly they are, most Saudi couples want to have a folkloric troupe perform for their wedding guests—because they expect it.

The al-Jishshah troupe includes teenagers as well as middle-aged men. After work and school, they regularly get together in the evenings to study and perform, because they love the old traditions and because there’s a regular demand for them to perform at weddings and other occasions.

Another Eastern Province group called Firqat al-Salam, or the Peace Troupe, is based in the old port town of Darin on Tarut Island, just off Saudi Arabia’s eastern coast. Spanning three generations, members study and perform the folk arts as a sideline to their main jobs working for Saudi Aramco, for the military or as teachers. They see their wedding performances as a community service. One member notes that, in the old days, weddings went on for five or six nights, but now they usually last just one. Still, the group is busy throughout the year performing for their friends and neighbors in the town.

Another Eastern Province group called Firqat al-Salam, or the Peace Troupe, is based in the old port town of Darin on Tarut Island, just off Saudi Arabia’s eastern coast. Spanning three generations, members study and perform the folk arts as a sideline to their main jobs working for Saudi Aramco, for the military or as teachers. They see their wedding performances as a community service. One member notes that, in the old days, weddings went on for five or six nights, but now they usually last just one. Still, the group is busy throughout the year performing for their friends and neighbors in the town.

The men of Darin once worked as fishermen and seafarers. Some of the group’s members are avid fishermen, too, but only as a hobby. Their repertoire includes the fjeiri (“until dawn”) songs of the pearlers and sailors, often sung late at night in special places dedicated to the art when the men were home from the sea. The art of fjeiri uses clay pots as earthy percussion instruments and has long rhythmic cycles, reminiscent of the slow, undulating waves of the Gulf carrying a dhow.

Firqat al-Salam also plays the African-influenced laiwa song style that features the surnai, as well as sev- eral unique percussion instruments—the tall mesondo, the sif tabl, made of cowhide and wood, and the biggest drum, the tabl ‘ud. Adding a snare- like tone to the drum section, someone plays the batu, a bowl atop an upside-down metal tray, with wooden sticks.

To demonstrate songs in the sawt tradition, a salon-music style that is practiced along the Gulf from Kuwait in the north to Qatar in the south (with variations as far south as Yemen), some group members pick up the violin and ‘ud and sit at the far end of two lines of men who kneel, facing each other. After a short improvisation on the ‘ud, they start into the song, and some of the men in the lines begin to play a small, cylindrical hand-drum, called the mirwas, in a percussion pattern that lightly punctuates the melody. When the clapping starts up during the instrumental refrains, a couple of the men jump up to dance freestyle. In the old days, friends would pass an evening listening to this music in the diwan, or salon, of a private home.

“The art of sawt is one of the most beautiful and profound types of music in the Gulf area,” muses Muhammad al-Jishi, a Saudi Aramco human-resources specialist from the east-coast town of Qatif. He plays the violin and composes music as a hobby. “The sawt I grew up hearing was coming from Bahrain and Kuwait. It has a rhythm that’s quite different from the Egyptian styles. It has spontaneity—structure mixed with improvisation.”

Public performance is not the primary goal of all folklore groups. The ancient city of ‘Unayzah in the northern Najd is set in an expansive date-palm oasis along an old road to Madinah. Its people were farmers as well as traders who had dealings with the Bedouin tribes and with more distant partners in Baghdad, Kuwait, Bombay and Cairo. The men of ‘Unayzah gather on Thursdays, the first day of the Saudi weekend, in the evening to sing poetry and perform their famous samiri folk songs. In the old days, they met in the sand dunes outside the city in summer; in winter, they gathered indoors. The weekly sessions continue today in Dar al-Turath, Heritage House, built for this purpose. While samiri is performed for weddings and other special occasions, ‘Unayzans also keep the tradition going for their own enjoyment.

A group of men from ‘Unayzah who live and work in Riyadh carries on the practice, meeting one night each weekend in a small home on the outskirts of town. There, under the stars in a courtyard, the multi-generational group talks about the events of the week, exchanges news of family and friends, and sometimes practices the samiri. There is no audience; members perform their art for their own pleasure.

Like other Saudi folk-music traditions, the samiri combines poetry, song, drumming and movement. But it is performed on the knees in unison. The repertoire of samiri poems is vast; the group in Riyadh keeps a large three-ring binder full of them. The songs take on the meter of the poetry, which in turn drives the playing of the drums by the singers.

In one hypnotizing song style, the singers start in two lines facing each other and go through a slow, choreographed sequence. One line claps and sings while the other sways from side to side, lifting and lowering drums in a highly stylized pattern, all the time playing them and singing. Suddenly, the men throw the drums on the ground with a loud slap, in a movement called khallu, or “leave it.” Then they lean to their neighbors to the right, then the left. When the sequence is over, they begin to clap in time so the other line can repeat the sequence. The men smile and laugh when they execute a difficult part perfectly.

Some samiri sequences are so complex that they take years to learn. Young people watch from the sidelines until they are ready to join in. They start by sitting on the ends of the line, only gradually working their way to the center, where the expert leader of each line, the mu‘allim, sits.

‘Abd al-Rahman al-Ruwaishid, 38, began to learn when he was seven, attending the weekly sessions in ‘Unayzah. “My father, who is more than 80 years old, always took me on Thursday nights when he was with his friends there,” he recalls. “I heard the drum and I moved with it. I grew up, practiced little by little, and now I can lead: Now I’m the mu‘allim. Thank God, I have a good memory and can keep all the songs and movements in my head.”

‘Abd al-’Aziz al-Garzaie, a retired medical-services officer who earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin, started learning samiri in the 12th grade. “It’s like doing aerobics,” he says. “In the morning your thighs and legs are really stiff, especially if you go two to three weeks between sessions.”

During a break in the samiri, a guest from the northern city of Tabuk brings out a one-stringed Bedouin instrument called a rababa and sings a traditional song of the desert. Others join in on the chorus. Bedouin poets and storytellers sing in unison with the rababa, which is played without percussion accompaniment.

After a traditional dinner of roast lamb served Bedouin-style on trays on the ground, the group demonstrates a folk art that is popular all over the kingdom, al-riddiyyah, a contest between two poets. One poet sings out a simple melody with two lines of poetry. Then the rest of the men, standing in two lines facing each other, repeat it several times while clapping and bending at the knees, until the other poet replies with his own spontaneous verse. The dueling poets pace up and down between the chorus lines. If one fails to reply, the other continues with a new line. Eventually, one poet concedes and the victor is declared, all in good humor.

f you visit the musical-instrument stores in the kingdom’s big cities, it’s easy to believe that young people are interested in both traditional and modern music. In the afternoons, the tiny shops in the instruments suq in Riyadh’s al-Hilla district are busy with customers. A university student and a couple of his friends test an electronic keyboard in one store. In other shops, employees and customers try out ‘uds and violins, their melodies spilling out and mixing together in the passageway that winds through the market. Business is good, the shopkeepers report. ‘Uds and guitars, both acoustic and electric, hang in the windows. Mountains of large frame drums are stacked to the ceilings.

f you visit the musical-instrument stores in the kingdom’s big cities, it’s easy to believe that young people are interested in both traditional and modern music. In the afternoons, the tiny shops in the instruments suq in Riyadh’s al-Hilla district are busy with customers. A university student and a couple of his friends test an electronic keyboard in one store. In other shops, employees and customers try out ‘uds and violins, their melodies spilling out and mixing together in the passageway that winds through the market. Business is good, the shopkeepers report. ‘Uds and guitars, both acoustic and electric, hang in the windows. Mountains of large frame drums are stacked to the ceilings.

The same is true in Jiddah. Samir Muhammad Badawi, who opened his first music shop 30 years ago in the old neighborhood where he grew up, now has five stores throughout the Red Sea city. “My father played ‘ud. When I saw it as a child, I loved the instrument. By the time I was 15 years old, I was playing ‘ud, violin and accordion,” Badawi says. Later he became a schoolteacher, but after work he played at birthday parties and weddings. He set up his first shop as a side occupation, and as the business grew, he was able to retire from teaching. Now his daughter works with him. “She’s in charge of importing,” he says.

‘Uds and guitars are his hottest-selling items. An array of tars and other drums fills most of the shelf space. A young man from a local folk troupe stops in to buy several large tars. He explains that his group is flying to Riyadh the next day to play at an event for a sports team.

audi Arabia’s Hijaz region in the west boasts famous song and dance styles such as the majrur and mizmar of Taif and Makkah. The Hijaz, which includes Jiddah, has an old and rich musical culture based on song traditions that have more complex melodies than elsewhere, expressed using instruments such as the ‘ud, qanun, nay and, more recently, the violin. The styles of the area reflect its role as a melting pot for Muslim pilgrims from all over the world.

audi Arabia’s Hijaz region in the west boasts famous song and dance styles such as the majrur and mizmar of Taif and Makkah. The Hijaz, which includes Jiddah, has an old and rich musical culture based on song traditions that have more complex melodies than elsewhere, expressed using instruments such as the ‘ud, qanun, nay and, more recently, the violin. The styles of the area reflect its role as a melting pot for Muslim pilgrims from all over the world.

Around midnight, Tarek ‘Abd al-Hakim draws on his water pipe and smiles at the roomful of friends gathered at his home north of Jiddah. “Folk music comes from Makkah and Madinah, the Hijaz,” he asserts. “Always the Arabs and Muslims came here on the hajj, and visited and mixed with our folk musicians. Of course, this was long before airplanes and ships, and they stayed for six months. Naturally, they mixed with us. They took things from us, and we took things from them.”

‘Abd al-Hakim is entitled to hold a theory or two about Saudi Arabia’s rich and varied folk music, particularly in the Hijaz. In addition to composing the melody of the national anthem, he wrote many songs that became popular throughout the Middle East, most of them steeped in the flavor of Hijazi folk music. He also authored several books on music. Above all, he’s a lifelong devotee of Saudi Arabia’s rich folk-music and dance heritage.

Born in a village near Taif, ‘Abd al-Hakim spent his career in the Saudi military, where he trained the kingdom’s first military bands. He was also a key figure in establishing the Saudi Society for Arts and Culture. He toured internationally with Saudi folk musicians and dancers, and in 1981 he won the prestigious UNESCO International Music Prize in recognition of his efforts to promote peace and cultural understanding by bringing Saudi music to a global audience.

The Hijazi wedding song styles of majass and daanah are specialties of Moustapha Iskandarani, a retired Saudi Arabian Airlines employee who had his own television show about music and later traveled to Morocco, Syria and Iraq to represent the kingdom at music festivals. The majass was sung by a professional singer, a jassis, when the family of the groom gathered outside the bride’s house before they signed the wedding contract. It praised the groom and congratulated both families. The melodies of daanah songs meander up and down, artfully interacting with a distinct 8/4 rhythm called shargain.

“My artistic life began at home,” Iskandarani explains as he tunes his ‘ud, which was made in Makkah by renowned craftsman ‘Abd al-Karim Sufi. “My family is from Makkah. My mother’s family was musical. They sang the old styles, the majrur and the daanah. That’s how I learned. I listened to them and stored them away, slowly, slowly.” Then the family moved to Jiddah, to Bait al-Sha‘arawi in the old quarter, and he made friends with many musicians who later became famous, including Mohammad ‘Abdu, Sami Ihsan and Siraj ‘Umar. “There was music continually around us, with parties and weddings, and I began singing at weddings,” Iskandarani says. He has composed several songs himself, using the traditional styles and rhythms of the Hijaz, while adding the sound of a fully instrumented Arab ensemble and sometimes employing electric guitar and keyboards.

After singing a short introductory poem in the improvised style of the majass, Iskandarani launches into his original Hijazi-style composition, “Gharibah Ya Zaman (Strange Times),” with his son Mhanna joining him on drums.

audi women, too, sing and perform folk music and folk dance to entertain themselves at all-women occasions such as wedding parties. In most Saudi cities and towns, you can find an ensemble or two of women that perform for the wedding night, haflat al-zaffaf, a big party for the women of the families of the bride and groom where musical entertainment is a must. They use the same songs and rhythms as the men, but also have some of their own, like the songs used specifically for wedding processions. Even the colorful Taifi majrur and samiri are also performed by women. Such folk and dance traditions from all over the kingdom are featured every year at the Janadriyah festival.

audi women, too, sing and perform folk music and folk dance to entertain themselves at all-women occasions such as wedding parties. In most Saudi cities and towns, you can find an ensemble or two of women that perform for the wedding night, haflat al-zaffaf, a big party for the women of the families of the bride and groom where musical entertainment is a must. They use the same songs and rhythms as the men, but also have some of their own, like the songs used specifically for wedding processions. Even the colorful Taifi majrur and samiri are also performed by women. Such folk and dance traditions from all over the kingdom are featured every year at the Janadriyah festival.

Decades ago, most women’s bands consisted of a singer, known as the mutribah, who was accompanied by a group of tar-playing drummers. In the cities, some of the singers also played the ‘ud and had violinists in their group. Today’s urban ensembles usually consist of a singer who plays an electronic keyboard especially designed to play the microtones of Arab music. At her side, she’ll have the traditional group of drummers, but the music takes on a more electronic sound, as it’s amplified to fill a large festival hall. They perform traditional songs, as well as modern popular Arab songs that they learn from recordings.

Fathia Hasan Ahmed Yehya, known as Tuha, is one of Jiddah’s most famous wedding singers and ‘ud players. She learned to sing and play from her father and brother. Over the decades, she has composed more than 100 songs and is still actively working on new pieces at her comfortable home studio, which is filled with memorabilia of her performing career. An avid scrapbooker, Tuha shares photos, programs and notices of her many performances abroad, as well as her collaborations with many regional musicians in the recording studio. Her work is highly influenced by the old Hijazi song styles. “My brother was a poet and musician. He would write lyrics and I would sing melodies,” she says. “I perform the traditional styles, the daanah, hadri (traditional vocal improvisation) and majass. I’ve been listening to these songs since I was a little girl. My brother was a great musician, an artist…. I’d start the idea and he’d complete it.”

Poets and musicians have been collaborating like this in Arabia for centuries. Ever since pre-Islamic times, singers and reciters helped spread poems among the tribes. This practice found its way to the courts of the caliphs, where celebrated singers set poems to melodies and performed them for private, elite audiences. During the 20th-century heyday of Egyptian song star Um Kulthum, this process became a leading art form in Arab popular culture. Poets like Egypt’s Ahmad Rami collaborated with the leading Arab composers of the day to create poetic and musical masterpieces just for Um Kulthum’s voice.

The practice has remained popular in Saudi Arabia all along. One of Tarek ‘Abd al-Hakim’s elementary-school friends in Taif was a son of King Faisal; he became an accomplished poet and asked ‘Abd al-Hakim to compose a tune for a poem he’d written. ‘Abd al-Hakim set the verse to a melody that was inspired by the music of the Hijaz and used the traditional rhythm from the majrur of his hometown. It surprised everyone when “Ya Reem Wadi Thaqeef,” a playful song admiring a young girl from Taif, took the Arab world by storm. Soon it was being broadcast throughout the Middle East on Egypt’s ubiquitous radio station, Sawt al-Arab, the Voice of the Arabs.

The song likens the girl to a reem, a gazelle fawn, of Wadi Thaqeef, a valley in the Taif area. ‘Abd al-Hakim claims that the melody traveled as far as Turkey, Iran and Mexico, where musicians came up with their own versions of the song. Lebanese songstress Najah Salaam, who popularized it, even named her daughter Reem in honor of the tune.

This kind of thing still happens. In 2005, a little-known composer from al-Hasa, Naser al-Saleh, got hold of a poem by Mansur al-Shadi, a well-known Saudi poet. He was inspired to write a melody, and later played it for Muhammad ‘Abdu, one of the middle generation of Saudi singers who has brought traditional Saudi song styles to wide popularity through similar poetic collaborations. “Al-Amakin (Places)” is a nostalgic song about a man who goes looking for his father in the locales he visited with him before he died. ‘Abdu liked it immediately and performed it in Jiddah for a live audience at the Summer Festival. The song was an immediate hit, marking another successful collaboration between musician and poet.

n a warm spring night at the seaside resort of al-Nakhil, north of Jiddah, the local Abu Siraj folk troupe demonstrates song styles from the western region like the mizmar, khubaiti and simsimiyah music. This polished group of professional performers has made many recordings in the 25 years since it was founded by a group of university students. Today, the troupe recruits younger members, owns a big sound system and brings a sound engineer to its performances—and even hands out promotional coffee mugs. The musicians perform on an open-air stage beside the blue waters of the Creek, an inlet in the Red Sea lined with stylish homes and resorts. A stadium-sized television screen next to the stage is tuned in to a Rotana music-TV channel, but the sound is muted. Tarek ‘Abd al-Hakim and his son Sultan are there, adding their comments about Saudi music and its history.

n a warm spring night at the seaside resort of al-Nakhil, north of Jiddah, the local Abu Siraj folk troupe demonstrates song styles from the western region like the mizmar, khubaiti and simsimiyah music. This polished group of professional performers has made many recordings in the 25 years since it was founded by a group of university students. Today, the troupe recruits younger members, owns a big sound system and brings a sound engineer to its performances—and even hands out promotional coffee mugs. The musicians perform on an open-air stage beside the blue waters of the Creek, an inlet in the Red Sea lined with stylish homes and resorts. A stadium-sized television screen next to the stage is tuned in to a Rotana music-TV channel, but the sound is muted. Tarek ‘Abd al-Hakim and his son Sultan are there, adding their comments about Saudi music and its history.

As the wind dies down after dusk, Rotana invites viewers to vote for the top Arab song of all time, using text-messaging. Someone notices that ‘Abd al-Hakim’s hit, “Ya Reem Wadi Thaqeef,” appears on the screen as an early contender, much to the composer’s delight. Attendees promptly open their cell phones and add their votes. Over the next half hour, the voting becomes fierce as the lead shifts among a few finalists.

At last it’s official. ‘Abd al-Hakim’s decades-old song, in a folk rhythm of Taif, set to a simple love poem about a country girl, wins. The composer laughs to see a younger, black-and-white image of himself on the huge screen, playing the ‘ud and singing the song. Just then, the Abu Siraj musicians begin a violin improvisation, introducing the next number. They call ‘Abd al-Hakim to the stage and hand him the microphone. Beaming, he belts out “Ya Reem,” mixing his voice with the chorus, their lively tasfiq, the tinkling sound of the qanun, and the strains of the electric violin. He has proved his point: Traditional Saudi folk music is still relevant in a text-messaging world.