Written by Lucien De Guise

Ikat Photographs Courtesy of The Textile Museum

Location Photographs From The Prokudin-Gorskii Collection, Library of Congress

The Silk Road is by no means the road less traveled these days.

The Silk Road is by no means the road less traveled these days.

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the founding of the World Tourism Organization’s Silk Road Tourism Project in 1994, there has been a steady rise in the number of visitors to Central Asia. Most come in pursuit of commerce, history, scenery or the romance of bygone empires. Tourists do not come, typically, to marvel at local sartorial splendor—but a century ago, before Soviet rule and the advent of the western suit, it was not uncommon for men on the street to compete vigorously with each other in the flamboyance of their clothes.

The key to Central Asian fashion was silk, traded across Asia for 2000 years. Pliny the Elder got it wrong about the Chinese and their most admired export: “The Seres are famous for the woollen substance obtained from their forests; after soaking it in water they comb off the white down of the leaves.” According to legend, silk production outside

China began with a princess who smuggled silkworms out when she was sent to marry a Central Asian prince.

|

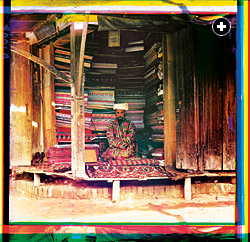

| A textile merchant in his shop in Samarkand, ca. 1910. |

Her sentiments might have resembled those in the following lines from the third-century Lady Wenji’s “Eighteen Refrains to a Barbarian Flute:”

I have left my beautiful country, China,

And have been taken to the nomads’ camp.

My clothing is of coarse felt and furs.

I must force myself to eat their rancid mutton.

How different in climate and custom are

China and this land of nomads.

By the 19th century, curiously, the trading positions of Central Asia and China had been reversed, and Chinese buyers sought out silk items made farther west. To add something extra to their best robes, Central Asian artisans of this era perfected one of the most elaborate textile techniques ever devised.

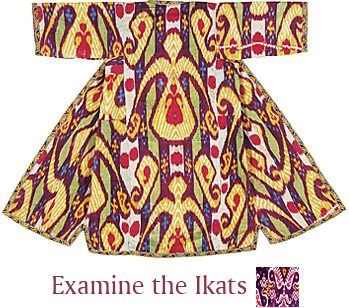

The skill in ikat is not so much in the weaving as the dyeing. Depending on how many colors are required, an ikat cloth could require as many as 10 dyeing stages. (See “Making Ikat,” page 20.) To viewers in search of the crisp colors and pattern definition that characterize woven and embroidered designs, the results might not immediately be seen as exceptional: “Out of focus” is a common description. This is, of course, part of the effect, and today, the dreamy, impressionistic look of ikats has become newly appealing. In an age of mechanization, it virtually spells “handcrafted.”

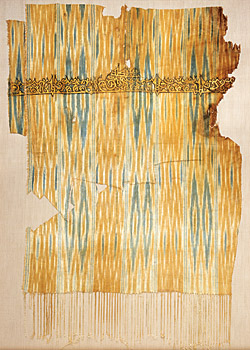

In centuries past, although ikats were widely admired, artisans in few parts of the world had the patience to create them. The main production centers were in pockets of Central Asia, India, Japan, Southeast Asia, parts of the Middle East and—in what scholars believe is a case of “parallel development”—Central and South America. We know less about the history of ikats than might be supposed. No textile can survive more than a few centuries unless buried in a dehumidified environment, and because Muslim funeral practices precluded the use of grave goods, it is particularly difficult

|

| METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART / ART RESOURCE |

| Attributed to a Yemeni workshop of the 10th century, this tiraz fragment is one of the earliest known examples of resist-dye weaving, or ikat. |

to determine when various types of textiles were first manufactured in the Islamic world. Although the oldest surviving examples are from the Middle East, where fragments of 10th-century Yemenitiraz ikats have been found, the earliest ikats were probably from India, where evidence of ikat-type cloths can be seen on the seventh-century Ajanta cave paintings in Maharashtra. It is assumed that the technique spread from there through the pan-Asian trade networks.

The word ikat comes, however, not from Central Asia, but from the Malay verb mengikat, “to tie.” Ikat is now the word used worldwide, even though the traditional word in Central Asia was abrbandi, which joins the Persian words for “cloud” and “workshop,” and in common usage, the term came to refer to both the woven products and the workshops. The region of Central Asia that took abrbandi to its greatest artistic height is now mostly within Uzbekistan, a former Soviet republic that has also been known by many names over time, including Transoxiana, Tartary and Mawarannahr, “what is beyond the river.” (The river in question is the Oxus, which defines the western side of the region, while the Jaxartes demarcates its eastern edge.) The land itself has never been the reason armies coveted it: Its strategic position astride the world’s greatest trade route was what made it worth fighting for.

The varieties of ikat are as different as the climates of hot, humid Southeast Asia and dusty, dry Central Asia. The Malay ikats have designs that are delicate to the point of being almost imperceptible, especially when generations of use have faded them. In Central Asia, the design spirit is as bold as the topography. But unlike the region’s vibrant tribal rugs, ikats were the products of the great cities of the region, especially Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva. In these cities, the most significant ethnic populations were Uzbeks and Tajiks, followed by dozens of other tribal and regional groups. In many centers, a substantial Jewish population was at the heart of the textile industry.

|

| The varieties of ikat are as different as the regions that produced them. Although Central Asian ikats have been less studied than South and East Asian ones, scholars assume they influenced each other. Ikat in the western hemisphere is a separate development. |

The ikats produced in the region had an honored part to play in domestic decoration, as wall-hangings that brightened rooms and as women’s garments worn in the home. In all its variations, there were different levels of ikat quality. The best used silk for both warp and weft; at the very top was a velvet weave that required an extra set of warp threads to make the pile. The plainest used

cotton in the weft and silk only in the warp. The patterns that were dyed and woven into the cloths used motifs that date back millennia and often appear also in other crafts, especially jewelry and architecture: the ram’s horn, amulet and tambourine are enduring favorites, along with the “tree of life” and the boteh (paisley).

Above all, color was the most vital ingredient in the luxuriance of ikat: the more colors, the more prestigious the result. Before inexpensive industrial aniline dyes brightened the look of all textiles in the second half of the 19th century with their harsher colors, the cloths of Central Asia were dependent on pomegranate peel for black dyes, crushed cochineal insects for deep reds, the madder plant for lighter reds and mauves, and other sources for a wide palette of greens, yellows, indigos, pinks and violets, all used extensively by the ikat dyers.

The arrival of aniline dyes brought traditional ways of dyeing to an end and, with them, the elegant ways in which natural colors faded that had been such a source of wonder, particularly in the West. At the same time, the export of textiles to Europe made ikats popular, although Europe never showed the same faddish demand for ikats as it did for Kashmiri shawls. (In Russia, the elite of Moscow and St. Petersburg held parties at which “exotic” garb from Central Asia was the theme.)

Today, over the last decade and a half, as the people of modern Uzbekistan have looked to their past for inspiration and identity, ikat has again become a popular choice. Much of the ikat revival has not involved silk but printed textiles made with acetate threads and aniline dyes. However, in the late 1990’s, with support from both local institutions and international cultural organizations, the Yodgorlik Handloom Weaving Mill in the Ferghana Valley, the main textile-weaving area of Uzbekistan,

|

| VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM / DICK DOUGHTY |

| Detail of a silk-warp man’s ikat robe, probably woven in Samarkand between 1860 and 1870. |

became one of the first to transform itself from a quota-driven Soviet-era mill to an artisanal manufactory using real silk and natural dyes. The result has been ikats that approach those of the 19th century “golden age” in their quality. Other manufacturers who have been reviving the old craft range from cottage weavers to other power-loom factories. Making the colors less harsh has been the greatest step forward, moving past the garishness that characterized the ikat of the 20th century.

This has awakened—following decades of Soviet-style enterprise—a spark of entrepreneurial self-interest. Many producers work in partnership with such non-governmental organizations as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the World Bank or Aid to Artisans, which have also helped build distribution networks and organize trade fairs. Most recently, customers are now not just tourists passing through, but on-line shoppers around the world. To cater to modern lifestyles, ikat workshops are no longer producing the voluminous masterpiece robes of 100 years ago: Instead, scarves are the most popular choice these days. Durable and light, they are an ideal mail-order item.

Thanks to this revival, silk ikats have regained much of their former popularity in Uzbekistan. They have become a symbol of cultural identity in a region where “cultural cleansing” was once an official Soviet policy. In Uzbek fashion festivals, ikats now often play a central role.

Other outsiders have noticed, too: Fashion designer Oscar de la Renta recently visited Uzbekistan and filled his fall 2005 collection with skirts and coats that drew from ikats. At the same time, designer Diane von Furstenberg unveiled her own tributes to the region. It’s a global visibility that, after decades of neglect, gives a bright future to one of the world’s great textile traditions.

|

|

| PHILIPPA WATKINS |

| Ikat dyers dip wrapped bundles of thread into a vat. Only those parts of the threads that have not been wrapped in cotton and wax will take on the color. Right: After dying, usually in several successive colors, is complete, the bundles are arranged on the loom and unwrapped to become the warp threads. |

|

| PHILIPPA WATKINS |

| Although the warp is silk, the weaver may use a simple cotton weft or, for a more luxurious fabric, a silk one. He can also add a supplementary silk weft to form loops that are later clipped to make a velvet fabric. |

There are three main stages to ikat: dyeing, weaving and the joining of woven strips.

The first entails stretching the undyed warp threads on a frame: The design of Central Asian ikats is created solely on the warp, not on the weft. The next step is to sketch on the threads an outline of the intended patterns. The threads are then removed from the frame, and water-repellent bindings of cotton and wax are tied to the parts of the threads that are not meant to be dyed in the first color. The threads are then immersed in the bath of dye. Afterward, the bindings are removed. The result is threads dyed along some parts of their length only. The dyed sections are now bound with more cotton and wax, and the bundled threads are immersed in a second dye bath. The dyer can, of course, overlap colors to mix them: For example, he could start with yellow, and then, if the second color is blue, he could plan for overlaps that will appear green. This process is repeated as many times as necessary to produce the color pattern the designer seeks.

When dyeing is finished, the threads are taken to the weaving workshops. In comparison to the enormous effort expended on dyeing, the weaving is relatively simple, if laborious. Using foot-operated looms, teams of weavers create lengths of ikat, often more than six meters (19') long, that can then be turned into wall-hangings or clothing.

The final stage creates width: Because the looms produce strips only about 25 to 40 centimeters (10–16") across, piecing them together to create a continuous pattern with minimal waste is the final challenge.

The dyers whose efforts were so essential to the process once occupied one of the lowest rungs on the social ladder. Those who engage in the ikat craft now are admired for a vision and talent that was generally not recognized in the past, even in their own lifetimes.

|

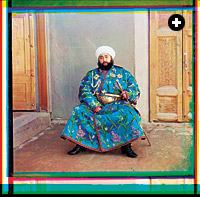

| Prokudin-Gorskii’s color photos from Samarkand, a few of which show men dressed in ikat robes, date to the early 20th century, probably between 1905 and 1915. This photo of a group of men above was made in the Registan, the city’s central square. |

|

| Much admired though silk ikats were, brocade was the material of the ruling class in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the few easily identifiable images that have come down to us from Central Asia’s era of prosperity is Prokudin-Gorskii’s portrait of Mohammed Alim Khan, the last amir of Bukhara, wearing striking blue robes of silk brocade. Not long after this photo was made, Alim fled Bolshevik expansion to exile in Afghanistan. |

During the late 19th century, ikat dyers were not the only craftsmen who were experimenting with color.

Photography was also being transformed, and among the pioneers of polychromy was Sergei Mikhailov Prokudin-Gorskii, a prolific Russian photographer who included Central Asia in his travels. When a subject as colorful as ikat textiles appears, it is a revelation to see images from an era we know mostly through monochrome brought to dazzling, full-color life.

Although Prokudin-Gorskii was not the first photographer to work in color, there is a richness to his work that is entirely unexpected from the early 20th century. This is partly because the images we see now are not prints from his own time. His photographs were originally projected onto a screen by registering three separate monochrome transparency images, each taken with a different filter of red, green and blue. Precisely aligned and illuminated with a projector, the three images appeared in full color.

Today, digital technology is recreating his photographs under the auspices of the us Library of Congress, which bought them from the photographer’s heirs after his death in 1944. The accuracy of the color can be verified by comparing a background feature in the photographs—the tiles on the wall of a building, for example—with the same feature as it is now. The match is almost perfect.

|

|

| The photo of the traders, left, was also made there. Although he did not record the location of the man with a water pipe, right, Prokudin-Gorskii framed the photo to include the ornate calligraphic inscription higher on the wall. |

|

Lucien de Guise (luciendeguise@yahoo.com) is the acting head curator of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (www.iamm.org.my). In addition to writing about art, he has edited the Malaysia’s Best Restaurants guide since 1993. |