Written and Photographed by Anna McKibbin

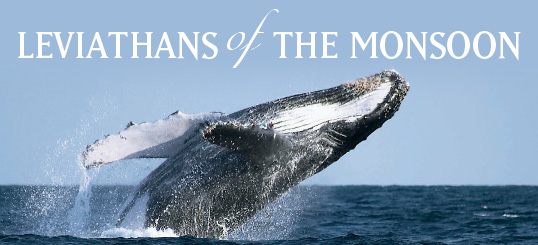

linging to the sides of our rubber boat as it bounces around on a sea of foam, we gape at the performance just in front of us. For perhaps the 20th time in succession, our visitor (above) heaves its vast bulk out of the water and crashes back down again, creating a wave that threatens to submerge us. Next it slaps its tail and its long pectoral fins repeatedly on the water’s surface—a frenzied finale that flings up sheets of fishy spray, forcing us to shield our cameras—until finally, exhausted by its gargantuan exertions, it takes a bow, lifts its tail flukes and slides noiselessly into the deep.

linging to the sides of our rubber boat as it bounces around on a sea of foam, we gape at the performance just in front of us. For perhaps the 20th time in succession, our visitor (above) heaves its vast bulk out of the water and crashes back down again, creating a wave that threatens to submerge us. Next it slaps its tail and its long pectoral fins repeatedly on the water’s surface—a frenzied finale that flings up sheets of fishy spray, forcing us to shield our cameras—until finally, exhausted by its gargantuan exertions, it takes a bow, lifts its tail flukes and slides noiselessly into the deep.

|

| Omani and international volunteers in 2000 founded the Oman Whale and Dolphin Research Group, which counts and tracks marine mammals through the waters off the southern Arabian Peninsula. |

We compare notes, trying to estimate the creature’s vital statistics. Acrobatics like this would be impressive if executed by a half-ton trained sea lion, but this is a humpback whale, some 12 meters (39') in length and with a likely weight of around 35 tons. We suspect its friskiness is breeding-related, and soon our suspicions seem to be confirmed: We’re just about to restart our engines when an unearthly noise reverberates through our boat. It starts as a deep chainsaw bass, then sweeps up the scale to a shrill chimpanzee whoop. We drop our underwater microphone over the side and record the sound. Our whale is singing, a noise created by forcing air through massive air cavities in its head. Only male humpbacks sing, and they do it only during the breeding season. We’re not sure whether this is to discourage rivals or to attract a mate—possibly both. To us, it doesn’t sound like much of a love song, but it could help us understand how this whale is related to other whales farther south.

Few people associate the Arabian Sea with an abundance of marine life, but the local wildlife here is keeping our team from the Oman Whale and Dolphin Research Group very busy indeed. We’re spending a month on an annual field trip to the remote Hallaniyat Islands, 100 kilometers (62 mi) off Oman’s southern province of Dhofar. We hope the trip will help us understand more about the whales and dolphins that inhabit these waters. It’s slow and painstaking work, and we’re using every research method at our disposal, including recording whale songs and taking DNA samples. Our transport is a 28-meter (93') oceangoing sailing dhow. Her slow speed is ideal for our purposes, and she comes equipped with a small inflatable boat that enables us to get close to any action. Provided, that is, we can find some animals to study.

| HANNE & JENS ERIKSEN |

|

| A pair of sperm whales—the world’s largest predator—swim on the surface in front of the research ship Sanjeeda. Below: With a span that can be as much as five meters (16'), the flukes of a blue whale are caught by the camera before slipping below the surface. |

|

Locating whales is never an easy task. They’re big, but the ocean is a whole lot bigger. One of the techniques we use is to look near their food. Beneath us are underwater cliffs where the seabed plunges from a few hundred meters’ depth to more than a thousand (3250'). They’re prime hunting grounds for squid and a good place to find the squid’s most fearsome predators— sperm whales.

Soon our efforts are more successful than we could have hoped. In front of us an aggregation of sperm whales, perhaps 50 strong, lies “logging” at the water’s surface. These are the world’s largest predator—giants of the deep, immortalized by the vengeful deeds of Herman Melville’s fictional Moby-Dick. They are capable of diving to depths of 2000 meters (6500'), where they stun squid with sonic clicks created in their enormous blunt heads. Now they are basking in the bright sun, taking turns sending up geysers, and then, one by one, lifting their tail flukes for another dive.

We record our encounters on sighting sheets, and the stack of them attached to my clipboard bears witness to our action-packed week: Vast schools of long-beaked common dolphins, 3000 strong, emerge from a pink dawn; smaller groups of Rissos dolphins, their smooth gray bodies heavily scarred by their fierce rivalries, cross our bows; a secretive beaked whale is glimpsed so briefly that the exact species can’t be confirmed; four rare blue whales, each the length of two London buses, frolic just

|

| A common dolphin calf leaps alongside an adult. |

offshore; and finally, three further lone humpbacks lure us in with their siren songs and allow us close enough to get a shot at them with our crossbow and biopsy dart. It’s a tricky operation requiring a steady hand, but the dart’s hollow tip collects genetic material invaluable to our work here.

It’s reassuring to know that marine life here is flourishing, but also a little puzzling. These tropical waters are crystal clear, with no sign of the green algae generally needed to support a mass of marine life, which raises the question: Where is all the food coming from? The answer lies thousands of kilometers to the east.

uring the summer months, temperatures in Oman’s capital, Muscat, climb to a sweltering 50 degrees Celsius (122° F). Farther south in Oman, however, the climate is very different. From the spring equinox through summer, warming air over southern Asia rises, creating a powerful weather system known to us as the southwest monsoon, and the southern Arabian Peninsula grabs a slice of it. Rain-filled mists transform the dusty landscape into a lush garden, while winds whip the sea into a frenzy of foam. During the monsoon, known locally as the khareef (“the time of ample rain”), fishermen pull their boats high up the beach and tend to their nets, but the storms that prevent them putting out to sea are vital to the following year’s catch.

uring the summer months, temperatures in Oman’s capital, Muscat, climb to a sweltering 50 degrees Celsius (122° F). Farther south in Oman, however, the climate is very different. From the spring equinox through summer, warming air over southern Asia rises, creating a powerful weather system known to us as the southwest monsoon, and the southern Arabian Peninsula grabs a slice of it. Rain-filled mists transform the dusty landscape into a lush garden, while winds whip the sea into a frenzy of foam. During the monsoon, known locally as the khareef (“the time of ample rain”), fishermen pull their boats high up the beach and tend to their nets, but the storms that prevent them putting out to sea are vital to the following year’s catch.

“It’s the strong winds,” explains Fergus Kennedy, a marine biologist working with our team. “They stir cold, nutrient-rich water up from the deep, in a process called upwelling. It kick-starts the entire food chain.

|

| Whale Behavior |

Whales exhibit various types of behavior when they surface. Humpback whales are among the most acrobatic and visible.

Breaching: Scientists aren’t sure why whales breach—that is, why they leap out of the water. One theory is that they use the thunderous splash created on impact (which can be heard underwater hundreds of kilometers away) as a means of communication. Or the impact may remove parasites from their skin, or stun prey fish. Whales have been recorded breaching continuously for over 90 minutes, achieving well in excess of 100 leaps.

Lobtailing: A whale “lobtails” when it slaps its tail or pectoral fins on the surface of the water. As with breaching, scientists think lobtailing may be a form of communication—possibly signaling aggression.

Spy-hopping: Whales can sometimes be seen lifting their heads out of the water with their bodies vertical, as if treading water, and this act is known as “spy-hopping.” They may do this to familiarize themselves with their surroundings—for example, to look at boats. Powerful individuals can spy-hop with half their body out of the water.

Logging: This term is generally used to describe sperm whales floating horizontally at the surface of the water. In this position, they resemble floating logs (above).

Bubble netting: Although it’s an activity we’ve yet to witness in the Arabian Sea, humpback whales often use a technique called “bubble netting” to catch fish. To do this, a whale will submerge beneath a school of food fish and exhale, blowing bubbles in a circle around the school. The fish move closer together, and the rising bubbles act like a corral so that they can’t escape. The whale can then move into the bubble net and surface with its mouth wide open, taking in huge gulps of fish-filled water. Whales often cooperate in using this technique. |

This is April, and the khareef is still a couple of months away, but in June these calm, clear waters will be transformed into a green soup, its surface erupting in washes of froth. Kelp forests will spring up among tropical corals, jellyfish will invade the waters in mythic numbers, and fish stocks will be replenished.

The monsoon is also crucial to Dhofar’s tourist trade. While the rest of the Peninsula sizzles in Arabia’s harsh summer heat, the fresh mists and balmy temperatures of southern Oman pull in tourists from across the region, providing a vital boost to the local economy. However, other visitors lured here by the monsoon have been less welcome.

The Soviet whaler Slava was passing through on her way to the Antarctic in 1963 when she first stumbled upon these waters. It was November, the southern-hemisphere summer and the season when the southern polar seas are transformed into a feeding ground for migrating blue and humpback whales. There, the Slava’s crew anticipated rich pickings. Their customary route south was through the Strait of Gibraltar and around the west coast of Africa, but this year, the Slava took a shortcut through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. It paid off: The clear, tropical waters of the Arabian Sea revealed an unexpected, astonishing wealth of marine life. Over the next four years, using a blockade of catcher vessels 100 kilometers (62 mi) wide, the Soviets swept the ocean, annihilating virtually every whale in their path and processing their catch aboard the factory ships Slava and Sovietskaya Ukraina. By the time the International Whaling Commission (IWC) managed to put an end to their covert activities, they had plucked an astonishing 3000 whales from the coasts of Oman and Yemen, including 1294 blue whales and 242 humpbacks.

ot until 1986 was a global moratorium on whaling implemented, but by that time an estimated 380,000 blue whales and 200,000 humpbacks had been snatched from the world’s oceans. With blue whales now endangered and humpbacks considered vulnerable, much of the work of our Oman Whale and Dolphin Research Group has been focused on trying to work out just how many humpback whales are actually left in these waters. It’s a project we’ve been working on for seven years, and we use a method called “mark-recapture.” The markings on each whale are unique to that individual, rather like a human fingerprint;

ot until 1986 was a global moratorium on whaling implemented, but by that time an estimated 380,000 blue whales and 200,000 humpbacks had been snatched from the world’s oceans. With blue whales now endangered and humpbacks considered vulnerable, much of the work of our Oman Whale and Dolphin Research Group has been focused on trying to work out just how many humpback whales are actually left in these waters. It’s a project we’ve been working on for seven years, and we use a method called “mark-recapture.” The markings on each whale are unique to that individual, rather like a human fingerprint;

|

| Researchers gather genetic material using a small, hollow-tipped biopsy dart. In addition, we can also retrieve naturally sloughed-off skin left in the water when a whale dives. |

we photograph the tail flukes and dorsal fin of each humpback whale we encounter. With that record, we compile a catalogue of all the whales we’ve seen, rather like a rogues’ gallery.

Back on board the dhow, we compare our photographs of the humpback who performed for us that morning with our database. It’s whale number OM01-003, better known to us as “Smooch” because of a kiss-shaped scar at the base of his dorsal fin—and in acknowledgment of his vocal talents. If the truth be told, we’re not entirely pleased to see him. The rate at which we re-sight humpback whales provides an estimate of population size, and it’s the high number of re-sights of individuals like Smooch that are leading us to a current population estimate of as few as 100 animals. As for blue whales, in the nine years we’ve been patrolling these waters, we’ve recorded just seven sightings. Those are sobering statistics when compared with the size of the Russian catch, but our work in this area also suggests that there may be something very special about the survivors.

Humpback and blue whales are baleen whales: This means that, despite their huge size, they feed exclusively on small fish and crustaceans, which they filter from the seawater using comb-like rows of springy, bristle-edged plates in their mouths called baleen, or whalebone. For them to find the vast quantities of food that these whales need to sustain themselves, scientists used to think that they conducted semiannual migrations, leaving the warm winter breeding grounds of the tropics to converge on summer feeding grounds at the poles. This meant that we should only expect to see whales here in the winter months—yet we were seeing them year-round. Why weren’t these whales migrating?

“Oman is in the northern hemisphere, and you’d therefore expect Oman humpbacks to spend the northern hemisphere’s summer in the Arctic,” explains Gianna Minton, a member of the team who completed her doctoral degree studying these whales. “However, one look at a world map shows the difficulties involved in that sea trip.” The route to the Arctic from the Arabian Sea is, indeed, entirely barred by the African and Asian land masses, but the route to the other pole—the Antarctic—is clear. Could the whales instead be making the longer round-trip to feed in the Antarctic instead?

|

| Research Methods |

Modern-day whale researchers have a number of tools at their disposal.

Photo Identification: The markings on the tail flukes of a humpback whale are unique to that individual, rather like a fingerprint. By taking photographs, we can build a catalogue of individuals. Counting the rate at which we re-sight them (a practice called “mark-recapture”) helps us calculate a population estimate, while identifying the same individual in different locations can shed light on seasonal and annual whale movements.

Line transect sampling: Mark-recapture programs take time to become established. A quicker method of obtaining population estimates uses the number of whales sighted along a given course traced by a boat or an aircraft to calculate a “whales per kilometer” figure. We can extrapolate from this to give an abundance estimate for a larger area.

Acoustic surveys: Whales in different geographical areas have very different calls. Recording these using a hydrophone (an underwater microphone) can help us understand the relationship between groups of whales and whale movements.

Genetic sampling: Analyzing whale DNA can provide basic information such as gender, and it can also help explain the relationship between populations of whales. Researchers gather genetic material using a crossbow (above, left) and small, hollow-tipped biopsy dart. In addition, we can also retrieve naturally sloughed-off skin left in the water when a whale dives.

Satellite tagging: Although expensive, satellite tags can help track the position of whales for long periods in open ocean. |

Given that whaling is the cause of their downfall, it is ironic that much of our knowledge of whales comes from whaling data. It took 29 years—and the collapse of the Soviet Union—for the true scale of Soviet whaling in the Arabian Sea to be revealed. But when former Soviet scientists finally broke cover, the catch data they published provided the key to unlocking what Robert Baldwin, author of the leading work on Arabian cetaceans, terms the “Arabian enigma.” Minton explains that around half the female humpbacks caught by the Soviets were pregnant, and that “the state of development of the calves suggested that the humpbacks were breeding here between January and May. It’s what we’d expect from a northern-hemisphere population, but it meant that they couldn’t be traveling to the Antarctic to feed: By the time they’d finished calving, it would be the southern-hemisphere winter.”

|

| It takes patience to catch sight of humpback whale flukes at a distance and angle that allow photo-identification, but with markings as individual as fingerprints, the resulting image allows researchers to both estimate population and compile a record of a single whale’s movements. |

Adding the Soviet data to our evidence of year-round sightings seemed to suggest only one conclusion: The whales were relying on the seasonal boost of the monsoon to sustain them here for 12 months of the year. They weren’t migrating at all.

The results from our other research methods point to the same conclusion. Humpback whales within any given geographic area tend to sing the same song, and this can vary greatly from one population to another. On initial analysis, the songs of Oman humpbacks have little in common with adjacent populations off the east coast of Africa, suggesting that those populations don’t come into contact with each other, which they might if the Oman humpbacks were migrating. Results of DNA analysis further suggest that the Oman whales are non-migrating residents of the Arabian Sea.

It’s a finding that could have important implications for conservation. Oman humpbacks and blue whales, it seems, are as unique as their South Arabian habitat, and the monsoon that once lured whalers here could help conserve the surviving population. At present, the Indian Ocean is a sanctuary from whaling—a measure introduced by the IWC in 1979—but current pressure for the reintroduction of commercial whaling means that it may not retain this status in the future. If the Oman humpbacks and blue whales constitute an isolated population, then we might be able to argue for the protection of at least those species of whales in order to preserve global genetic diversity.

Our own time in the waters off Dhofar is at an end. The whales may stay here year-round, but we cannot. The winds have started to pick up, signaling the start of the khareef. We pack up our equipment and prepare to return to Muscat. We’d like to stay longer, but we know that the gales that evict us from the sea will sustain these leviathans until we return again.

|

Anna McKibbin is a writer and photographer focusing on natural history and the environment. She is a trustee of the Indian Ocean Research and Conservation Association, a non-profit committed to the conservation of natural resources. She can be reached at anna@digital-diaspora.com. |