| Written by Richard Covington |

Photographed by Thorne Anderson |

|

| Dr. Fuat Sezgin, 82, is framed by the rings of an armillary

sphere in his Institute for the History of Arab–Islamic Science

in Frankfurt. He established the institute in the late 1970’s

after winning Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal Prize for science. Below: The institute is located in a villa in a quiet neighborhood in Frankfurt. It houses the most comprehensive collection of texts on

the history of Arabic–Islamic science in the world, and contains more than 800 replicas of scientific and engineering innovations. |

|

ike a kid in a

toy store, Fuat Sezgin, still spry at 82, can barely suppress his

enthusiasm as he shows

off the 800 exhibits

that fill the museum of Arabic–Islamic science he’s

built up in Frankfurt over more than two decades. This little-known

treasure house of astrolabes, water-lifting machines, automatons,

globes, maps, clocks, balances, weapons, surgical tools and

astronomical and architectural models

is unequalled in the world.

ike a kid in a

toy store, Fuat Sezgin, still spry at 82, can barely suppress his

enthusiasm as he shows

off the 800 exhibits

that fill the museum of Arabic–Islamic science he’s

built up in Frankfurt over more than two decades. This little-known

treasure house of astrolabes, water-lifting machines, automatons,

globes, maps, clocks, balances, weapons, surgical tools and

astronomical and architectural models

is unequalled in the world.

“Wonderful, wonderful!” the exuberant Turkish-born

science historian says with a chuckle as I activate a 2.3-meter-tall

(7'6") clepsydra, or water clock, a brightly colored Rube Goldberg

contraption that tells time. Every half-hour, enough water fills a

floating basin inside the stomach of a wooden elephant to cause the

basin to sink, pulling strings that release a ball that rolls out of a

latticework tower into the mouth of one of a pair of joined serpents.

Under the weight of the ball, the heads of the serpents fall, raising

their tails; this simultaneously starts a scribe writing and triggers a

figure in the tower to lift its left hand on the half hour, its right

hand on the hour. Strings attached to the rising tails also raise the

basin back to the floating position to start the process over again as

a drummer seated atop the elephant’s head smartly taps out

two beats and the ball clatters into a barrel. Ta-da! Who said science

couldn’t be silly?

Part Ali Baba’s cave, part science fair, the museum occupies

two floors of a stately, three-story villa on the grounds of Johann

Wolfgang Goethe University. It contains very sophisticated toys indeed,

modern reproductions of ancient instruments. Some were fashioned by

Mahmut Inci, a Turkish-born designer who makes prototype scale models

for Mercedes Germany. Swiss clockmaker Martin Brunold fabricated a

number of the astrolabes, and Ayman Mohammed Ali Ibrahim, an

instrument-maker in Cairo, created others, employing traditional

techniques that eschew chemical solvents and electrical tools.

The collection gives science a three-dimensional reality, making it

immensely easier to visualize complex concepts that are well-nigh

unfathomable on the printed page. Studying an elaborate model of a

waterwheel powering a six-piston pump, a device invented by the

16th-century Arab engineer Taqi al-Din, I finally understand the

design, which had left me mystified when I originally read about it.

|

| METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART / ART RESOURCE |

| The water clock

model at the institute (below) tells the time, and fascinates anyone

watching, with a series of intricate, hydraulically driven movements. It mirrors the

Elephant Clock from al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious

Mechanical Devices (above), written in the early 13th century. |

|

“Now I get it,” I blurt out to Sezgin in a

“Eureka!” moment. Beaming,

the white-haired professor gives me

a knowing nod and moves on briskly to an ingenious steam-powered

turnspit for roasting meat, also invented

by the prolific engineer.“A hundred years after Taqi al-Din created this simple steam

engine, Italian designers put wheels on it to fabricate a rolling chair

that they presented to Kangxi, the 17th-century Chinese

emperor,” Sezgin explains.

The Indiana Jones of Islamic manuscripts, a tireless bibliographer who

has tracked down more than 400,000 texts from Oxford to Oman and

Kashmir in half a century of passionate research, Sezgin has made the

propagation of Muslim science a lifelong crusade. When he became the

first recipient of Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal Prize for

science in 1978, he persuaded Jaber al-Ahmad al-Jaber Al Sabah, the amir of Kuwait, to purchase the villa that now houses the

museum and the Institute for the History of Arabic–Islamic

Science, which Sezgin created at the Frankfurt university. He also

donated his entire prize—200,000 marks (around $97,000 at the

time, approximately $290,000 today)—to the institute

and persuaded government ministers from Saudi Arabia, the United Arab

Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Jordan, Syria, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and

Morocco to help finance its operation.

Sezgin’s original notion for the museum grew out of a

determination to make it easier to comprehend hard-to-picture text

descriptions of scientific instruments. The first exhibit was a model

of al-Jazari’s animal-powered machine that used waterwheels,

gears and pumps to raise water. The idea was a hit: From the 20

exhibits he had initially imagined, the museum has mushroomed to

display some 800 pieces for select groups of students, scholars,

scientists and diplomats—

a total of around 4000 visitors a year. For most guests, the breadth of

the collection comes as a dazzling surprise.

“Muslims themselves do not really know the extent of their

own contribution to European science and the Renaissance,”

laments Sezgin, surrounded by floor-to-ceiling books in his

light-filled office. “What little they do know about the

subject they owe to the work of European Orientalists who started

researching Islamic science in the 19th century.” (See

“Lines of Transmission”).

Sezgin has certainly made a valiant effort to spread the

word—many words, in fact. His institute publishes

a huge booklist comprising around 1300 academic treatises and

monographs written in German, English, French and Arabic on a wide

range of subjects, including geography, mathematics, medicine,

astronomy and physics. Sezgin himself is the author of the encyclopedic 12-volume series Geschichte des arabischen

Schrifttums (History of Arabic Literature), which covers many

manuscripts on Muslim science. At a ceremony in Tehran in February

2006, he won the Iranian World Prize for Book of the Year for the

French version of his five-volume work Science et Technique en Islam, which provides a beautifully illustrated catalogue of all the objects

in the institute’s museum. (German and French versions are available

under the heading “Natural Sciences of Islam” at www.uni-frankfurt.de/fb13/igaiw. English, Turkish, Arabic and

Persian translations are in various stages of preparation.)

“When the Iranian president asked me for his own personal

copy, I gave him one,” the professor explains, “but I made sure to emphasize the debt Islamic science owed

to the French and German Orientalists.”

Everywhere he travels in the Muslim world, Sezgin finds an overwhelming

curiosity about the achievements of medieval Arab and Muslim scholars.

After a series of lectures in Istanbul, he received some 200 letters

from people thanking him for opening their eyes to Islamic science. In

Cairo, local newspapers report on his lectures because there is so

little knowledge about the subject. “To the Egyptians,

ancient Muslim science is almost breaking news,” he says.

Tucked away in a quiet, leafy neighborhood about a 1.5 kilometers (1

mi) from downtown Frankfurt, the institute is a world away from the

high-powered financial centers that the city is famous for. Inside,

there is a rarefied aura of scholastic tradition, a feeling that here

an essential chapter of global civilization is being preserved and

passed on. Lining the stairwell are engraved portraits and vintage

photographs of such revered Orientalists as Carl Brockelmann and

Eilhard Wiedemann, music specialist Henry George Farmer and, crucially

for Sezgin, Hellmut Ritter, his life-changing mentor at Istanbul

University.

|

| Galleries at the Institute for the History of

Arab–Islamic Science are packed with reproductions of

astronomical and navigational instruments. |

Upstairs in his office, the professor recollects how Ritter, one of the

world’s leading Orientalists and a famously demanding teacher

who insisted that students learn a new language every year, took the

19-year-old aspiring engineer aside one day and recommended that he

broaden his background in mathematics and physics by reading

the works of al-Khwarizmi, Ibn Yunus, al-Biruni and al-Haitham.

“I had never heard of them,” Sezgin recalls with a

laugh. “But I stayed up all night poring over their books,

ones Ritter had lent me, and the next day he took me to

Topkapı Saray library to show me al-Jazari’s Kitab

fi ma‘rifat al-hiyal al-handasiyya (The Book of Knowledge of

Ingenious Mechanical Devices). I decided right then and there that [the

history of Muslim science] was the research I wanted to dedicate my life to.”

In 1960, Turkish generals overthrew the ruling Democratic Party. Even

though Sezgin had been very little involved in politics, he was among

147 academics dismissed from Istanbul University in the wake of the

coup. Disgusted by the new regime, the

36-year-old professor left the country voluntarily to take up a

position as a visiting lecturer of natural science at the University of

Frankfurt.

Shortly before leaving Istanbul, Sezgin remembers telling one of his

Turkish colleagues of his ambition to compile a bibliography of all the

manuscripts in existence on Islamic science.

“Impossible,” sniffed the man. But Sezgin set out

to prove him wrong, devoting more than three decades to

the search, uncovering manuscripts

in England, Europe, Africa, Russia, Turkey, the Middle East and India.

Although he has not traveled to the United States, the Frankfurt

scholar has drawn on catalogues from American libraries and private

collections for manuscript listings.

|

| Top: Through a feat of engineering, 12 oil lamps burn in

succession to create an elegant “fire clock.” Above: The

model of the camera obscura on display at the institute is based on an

explanation by its 11th-century inventor, Ibn al-Haitham. The device

was an early progenitor of modern photography devices. |

After locating more than 400,000 texts, if Sezgin hasn’t

found all the medieval Muslim scientific writings extant, he probably

hasn’t missed too many. In his opinion, the most important

manuscript he discovered was

a copy of a landmark map drawn up for the ninth-century caliph al-Ma’mun. He stumbled across

it in 1984, in a 1340 encyclopedia at Istanbul’s

Topkapı Library as he was making a facsimile of the book.

“Ma’mun’s map was a giant step

forward,” Sezgin explains. “It gives the first

really accurate representations of longitude and the circumference of the Earth.” For example, where Ptolemy estimated the

distance from the Canary Islands—then regarded as the westernmost point of the world—to the eastern shores

of the Mediterranean as 63 degrees of longitude,

al-Ma’mun’s cartographers calculated a

substantially smaller figure that is only two or three degrees off the

true 50-degree measurement. They also depicted the Atlantic and Indian

Oceans as open bodies of water, not land-locked seas as Ptolemy had

done.

Back down in the museum, Sezgin shows me a model of

al-Ma’mun’s globe, vividly painted in gold and blue

with red bands indicating mountain ranges and thin green lines for

rivers. Nearby is a copy of Muhammad al-Idrisi’s 12th-century

world map, first engraved for Roger ii, the Norman king of Sicily, on a

ponderous 135-kilogram (300-pound) silver plate two meters (78") in

diameter. Although the later map distorts the known world by squeezing

land masses and oceans into seven equal climatic zones, it provides

considerably more detail on northern Europe, northern Asia and the

islands of what is now Indonesia.

Among the institute’s 25 elegant compasses made of wood and

brass, with magnetized iron needles, perhaps the most historically

significant is the simple copper ring with Arabic lettering designed by

Ahmad ibn Majid, the great Arab navigator. According to Sezgin, Ibn

Majid was the first to mount a magnetized needle on a revolving support

above the compass face. Earlier, the professor had eagerly hauled out a

copy of one of Ibn Majid’s maps, probably similar to one

employed on Vasco da Gama’s 1498 voyage from East

|

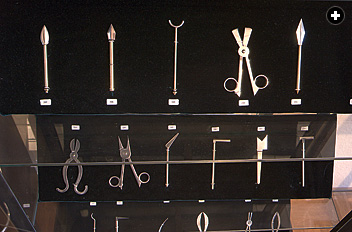

| A display presents replicas of the earliest instruments for eye surgery. |

Africa to

India, and marveled over its accuracy: It pegged the distance between

Africa and Sumatra to within 40 minutes of a single degree of

longitude, off by the equivalent of around 74 kilometers (46 mi).

“Eighty percent of the history of cartography until the 18th

century dates from the medieval Islamic period,” Sezgin

asserts. “Only 20 percent came from the ancient Greeks and

from later European sources.” As proof, he lays before me

copies of Chinese and Korean maps that use Arab, not European, place

names, and a 1669 French map by Nicholas Sanson that also recycles

Arabic longitudes and latitudes. Sanson’s map repeats a

mistake al-Ma’mun had made about the location of Balkh, in

northern Afghanistan, 800 years earlier. Since Muslim cartographers had

corrected the error by the 16th century, it is clear that Sanson,

working more than a hundred years later, was copying

al-Ma’mun’s original map, Sezgin says.

Wandering through the museum provides an eye-opening course in eight

centuries of Muslim science and Europe’s liberal

appropriation of Islamic discoveries. In one room are 10 instruments that the 16th-century Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe modeled on

instruments from the 13th-century Maragha observatory in northwestern

Persia. Among the dozens of gleaming brass astrolabes and

equatories—related instruments used to determine celestial

longitudes—is one designed on an Arab model by Geoffrey

Chaucer, the 14th-century English author of The Canterbury Tales, to

instruct his son

in astronomy.

|

| A replica of the globe commissioned by the ninth-century caliph Ma’mun

bears witness to the remarkable accuracy of Muslim cartographers. Below: A reproduction of a 14th-century candle clock shows how screws released in rapid succession freed metal balls

to chime bells in a rough measurement of equal hours. |

|

Muslim clocks were some of the most ingenious ever created. One

extraordinary reproduction in Sezgin’s museum, modeled after

an original timepiece from 13th-century Toledo, has hands that move as

mercury shifts from compartment to compartment around a wheel. The

steadily moving weight of the mercury rotates the wheel through a

complete cycle in

24 hours. In addition to showing the hours and sounding them with

bells, the clock face represents an astrolabe that indicates the

position of the sun and stars. More than three centuries later, in

1598, Attila Parisio, an unscrupulous Venetian watchmaker, wrote a book

claiming that he had invented the device. And in 1656, the Campani

brothers presented a similar clock to Pope Alexander vii, no doubt

omitting to mention its Muslim origins.

Elsewhere in the museum is a delicately incised 12th-century brass

balance with a miniature bowl at one end that drips water with such precise regularity that the

counterweight at the other end tracks time in minutes. “This

was unheard of in the history of science,” marvels Sezgin.

“The Greeks could mark time in 15-minute intervals, but no

one before had managed to divide it into minutes.”

Amid cases holding pear-shaped alembic jars and a cylindrical brass

tower sprout-ing glass retorts with long curved necks, used to distill

rosewater, is a 1.5-meter-

tall (5') still with coiled pipe running through cold-water basins. It

is a reproduction of a 16th-century German apparatus that was modeled

after

a design by the 10th-century Andalusian doctor Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi

(known

as Abulcasis in the West).

Anticipating Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machine by more than

600 years, the Córdoban polymath Abbas ibn Firnas concocted

a rudimentary glider in the ninth century that is represented in the

museum with leather straps and cloth wings. Looking more like a contemporary

hang-glider than Leonardo da Vinci’s design, whose weight

kept him Earth-bound, Ibn Firnas’s glider managed

to stay aloft for a few meters, Sezgin assures me, though its

70-year-old designer later died of back injuries

suffered during his crash landing.

Despite his irrepressible energy and inveterate optimism, the professor

is far from encouraging about the future of Islamic science.

“In Turkey, Egypt, Iran and a few other countries in the

Middle East, there are a handful of universities offering courses in

the history of Muslim science, but so far, the education is not at a

very high level because there is a critical shortage of

teachers,” he complains. Germany and the UK have suffered a

decline in interest in recent years, although there is a small surge in

programs in the US, he notes. On the plus side, Granada’s

Science Museum is planning a new wing devoted to the Arab era, and

Turkish cultural officials have recently signed a contract with Sezgin

to open a new Muslim science museum at the Süleymaniye complex

in Istanbul that will draw on the Frankfurt collection.

|

| The Muslim

compass used in the Indian Ocean around 1500 (right) had improved on

the 32-point compass used in the West at the same time, allowing Muslim

sailors to make more precise navigational calculations than their

European counterparts. |

“So the interest is there, but it’s very difficult

work to carry on the history of Islamic science,” he says

with a sigh. For starters, competent scholars need to be conversant in

Arabic, German, French, English and, ideally, Turkish—like

Sezgin. When I point out that this is a very tall order, if you also

throw in possession of a modicum of knowledge of astronomy, mathematics

and other scientific disciplines, Sezgin nods his head in agreement.

“That’s why our work here in translating the scientific documents is so crucial,” he says.

Not to mention the exhibits themselves, which should be viewed by

hundreds of thousands rather than a mere 4000 visitors a year. Putting

these highly engaging displays on tour could work miracles for

educating the public about the depth and ingenuity of the Muslim

contribution to science, Sezgin readily agrees, but so far no

government, international organization or museum has come forward with

a feasible plan—with the possible exception of the Turkish

project. If the venerable professor is to have any success in his

campaign to carry on the long tradition of Muslim scientific

scholarship and research, this illuminating intellectual road show

should quickly get on the move.

|

|

|

Paris-based author Richard Covington writes about culture, history and science for Smithsonian, The International

Herald Tribune, U.S. News & World Report and the London Sunday Times. His e-mail is richard peacecovington@gmail.com. |