|

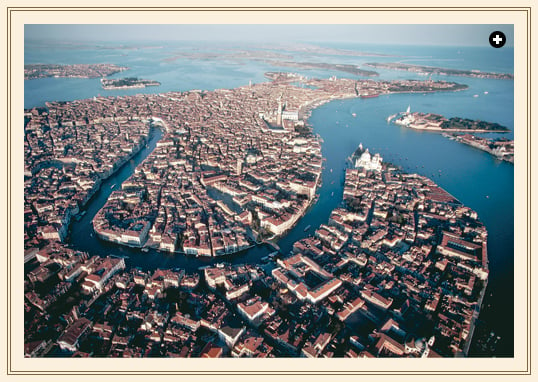

| JONATHAN BLAIR / CORBIS |

| Venice’s Grand Canal curves east at its mouth and opens toward the Mediterranean—and the world. It served as Europe’s maritime gateway to Turkey, the Levant and North Africa for more than a millennium. |

Written by Richard Covington

|

| SARAH QUILL / VENICE PICTURE LIBRARY / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

Top: On a quiet canal, the Palazzo Zen was the home of one of Venice’s great trading and exploring families. Nicolo Zen, a 14th-century envoy to Cairo, brought home the bold design of Venice’s famous Doge’s Palace. Below: A 13th-century statue of a “Moorish” trader sports a later, comically oversized turban. |

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Through binoculars, I can barely make out the palm trees, gazelles, camels and other Middle Eastern images on the Palazzo Zen, ancestral home of one of the most prominent Venetian families involved in diplomacy and trade with the Islamic world.

“The entire façade was once covered with frescoes recounting the Zen family’s contributions to the Venetian Republic,” says Concina. “The frieze was a memento of Caterino Zen the Elder’s mission in the 15th century to the Turkmen khan Ozun Hasan in Persia.”

What an amazing family it was! Nicolo Zen explored Greenland and the Orkney Islands in 1393–1395. In 1398, his brother Antonio made it as far as Nova Scotia—or so claim Frederick Pohl and other historians. Daragon Zen traded in Arabia in the 15th century. In the 16th century, Pietro Zen was vice-consul in Damascus and voted unsuccessfully against war with the Ottomans in 1537. Pietro’s son Francesco wrote the earliest western book praising Turkish architecture, and another son, Nicolo, compiled a history of the Abbasids. The Zen chapel in the Basilica of St. Mark was constructed in the 16th century as the funerary chapel for Cardinal Giovanni Battista Zen.

Venice’s fortunes, like those of the Zen family, have been inextricably linked to the Islamic world at least since the eighth century, when her merchants began trading with Alexandria. In this long-running tale of interdependence, the Adriatic city was a gateway to the Middle East, giving Muslims a taste of Europeans as businessmen rather than Crusaders.

The Venetian Republic was “an entrepôt for the importation into Europe of profitable luxury goods such as carpets and textiles, and opened a European door to the Islamic cultures that created those goods,” writes Walter Denny, an art professor at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, in the catalogue for “Venice and the Islamic World.” This landmark exhibition of art, ceramics, metalwork and fabrics ran at the Arab World Institute in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Venice’s own Palazzo Ducale last year.

From the cupolas, pointed arches and gilt mosaics of the Basilica of St. Mark to the labyrinth of winding streets that Cambridge University architectural historian Deborah Howard compares to a “colossal souk,” Venice has borrowed liberally from Muslim architecture and urban design. (See “Seeking Islamic Venice.”)

|

| ALFREDO DAGLI ORTI / MUSEO CORRER, VENICE / BILDARCHIV PREUSSISCHER KULTURBESITZ / ART RESOURCE |

| Venetians, Turks and others would have met in markets like this one in the Jerrahpasha district of Constantinople, across the Golden Horn from the Venetians’ trading centers. The spiral column shown in this illustration from a 16th-century Ottoman manuscript was erected in about 405 by the Eastern Roman emperor Arcadius. |

Inside the Muslim cities of Alexandria, Constantinople (later renamed Istanbul), Damascus, Acre, Aleppo, Trebizond and Tabriz, the Republic created mini-Venices, commercial enclaves overseen by a bailo, or consul, complete with churches, priests, merchants, doctors, barbers, bakers, cooks, tailors, apothecaries and silversmiths.

“Abroad, Venetian diplomats and merchants traveled throughout the Islamic world, from the Nile Delta to Syria to Constantinople to Azerbaijan,” notes Denny, “and their relazioni or reports to the Venetian authorities still serve as important documentation of Islamic politics, history, economics and art.”

Without Muslim trade, Venice would simply not have existed. Instead of the powerful maritime republic, “La Serenissima,” that dominated Mediterranean commerce from the 12th to the 16th century, the lagoon settlement would likely have remained a fishing village.

But of course, there was trade—arguably the greatest the world had known. Silk, spices, carpets, ceramics, pearls, crystal ewers and precious metals arrived in Venice from the East, while salt, wood, linen, wool, velvet, Baltic amber, Italian coral, fine cloth and slaves went to Egypt, Anatolia, the Levant and Persia.

“Who could count the many shops so well furnished that they also seem warehouses,” marveled the Milanese priest Pietro Casola on a 1494 visit to Venice’s Rialto, “with so many cloths of every make—tapestry, brocades and hangings of every design, carpets of every sort, camlets of every color and texture, silks of every kind; and so many warehouses full of aromatics, spices and drugs, and so much beautiful white wax!” (Presumably, the priest was happy to locate wax suitable for votive candles.) It was a somewhat one-sided business, since trade with Venice was a relatively minor aspect of the Mamluk and Ottoman economies. Nonetheless, the Republic was important enough to be the only Christian city to appear on Ibn Khaldun’s 14th-century world map. Yet for Venice, on the other hand, Muslim trade represented fully half the Republic’s revenues.

|

| BRAUN & HOGENBERG, CIVITATES ORBIS TERRARUM (CA. 1572) |

| A detail from a 16th-century view of Venice shows the arrival of both lateen- and square-rigged ships. |

Christian pilgrims flocked to the city from across Europe to sign on for package tours to the Holy Land. These visitors were so critical to Venice’s economy that they were invited into the Palazzo Ducale to be individually embraced by the doge himself, and sailings were sometimes delayed on purpose to force the faithful to linger longer, and spend more money, before departing for Jaffa. On separate galleys, Venetian merchants collected Muslim pilgrims in Tunis, Djerba and Alexandria and brought them to the Levant en route to Makkah.

The 13th-century Venetian Marco Polo brought back tales of the fabulous Middle and Far East, of course. But there were other, less famous travelers, such as 23-year-old Alessandro Magno, whose 16th-century diary portrays daily life in Alexandria and Cairo with ink sketches of typical house interiors and sights like the Sphinx and pyramids at Giza. (Like Venice, each city had around 150,000 residents.) Although Magno was a tourist, many young Venetian noblemen spent years at a time learning Arabic and bookkeeping in their homeland’s far-flung commercial outposts. Other visitors were bowled over by Muslim craftsmanship. After inspecting pieces of delicately incised inlaid metalware in Damascus, 14th-century merchant Simone Sigoli breathlessly declared, “If you had money in the bones of your leg, without fail you would break it to buy these things.”

Numerous Arab words were absorbed into Italian, including trade terms such as doana (customs) and tariffa (duty) and the names of luxury goods such as sofa, divan and damasco. A gold ducat was a zecchino, taken from the Arabic word sikka, or mint.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Above: A palace built on the Grand Canal in the mid-13th century was allocated to the city’s Turkish merchants in 1621 as warehouse and living accommodation, and was thereafter known as the Fondaco dei Turchi. Today it is Venice’s natural history museum. Below: At the eastern end of the Mediterranean, the Khan al-Umdan at Acre offered similar facilities to Venetian traders. |

|

| MASSIMO BORCHI / ATLANTIDE PHOTOTRAVEL / CORBIS |

As the chief European center for publishing, Venice also printed many Arabic texts in Latin and Italian translation, including the Canon, the standard medical reference book by Persian physician Ibn Sina (called Avicenna in the West), and commentaries on Aristotle by 12th-century Córdoban philosopher Ibn Rushd (known in the West as Averroës). Even the first printed text of the Qur’an was published in Venice in 1537–1538 by enterprising local booksellers aiming to crack Arabic-speaking markets. Riddled with errors, the edition proved a dismal failure, but it did inspire translation into Italian in 1547, according to Stefano Carboni, the curator for the Met exhibition.

“From the last years of the 15th century onward, Venetian publishers printed Muslim treatises on medicine, philosophy, astronomy and mathematics,” explains Giandomenico Romanelli, the director of the city’s Correr Museum, an extensive repository of art, ceramics, maps and manuscripts. Elaborately tooled leather bookbindings made in Venice were modeled after those of Istanbul, Tabriz and elsewhere in the Muslim world, he notes. In publishing, trade, diplomatic relations and pilgrimages, “Venice was the hinge between East and West,” says Romanelli.

The connection is deeply entrenched in myth and history. According to legend, two Venetian merchants spirited away the bones of St. Mark from Alexandria in 828, hiding them in a basket beneath a shipment of pork. Images of the episode appear in mosaics on the façade and ceiling of St. Mark’s Basilica, which was built to house the saint’s remains.

To Venetians, possessing the relics of St. Mark gave the city a holy status to rival Rome, the seat of western Catholicism. The Republic set about establishing its reputation as the new Alexandria, where the evangelist had preached and been martyred. In the 15th century, a campanile tower was erected at the Basilica of San Pietro Castello in homage to the famous Pharos, Alexandria’s ancient lighthouse. Paintings by Gentile Bellini, Giovanni Mansueti and Vittore Carpaccio mingle Venetian and Alexandrian backdrops in scenes depicting St. Mark.

The recent exhibition was designed to illustrate Venice’s status as a “privileged partner”of the Islamic world, says Carboni, who was himself born near the Rialto and has devoted the past two decades to studying the artistic exchanges between Venice and the East.“Venice is usually associated with Byzantium, not the Islamic world,” he explains. “But I wanted to surprise the public with the breadth of artistic, cultural, mercantile and diplomatic connections.”

Fleeing Gothic and Lombardic tribes in the fifth century, settlers from the Italian mainland took refuge on the Adriatic lagoon islands that would become Venice. Driving piles into the seabed, the refugees gradually enlarged the islands and built bridges linking them. Lacking arable land, the earliest Venetians relied on fishing and trade, declaring an independent republic in 726 and erecting the first fortress for the doge, or duke, and the government in the ninth century. After sacking Constantinople in 1204, the Venetians adorned their city with loot from the Byzantine capital, ushering in a golden age of commerce with the Middle East and the Orient that lasted some four centuries. By the 16th century, the population of Venice was around 150,000, roughly the same as Cairo’s, and the city was filled with artistic and architectural masterpieces. As Portuguese, Spanish and English explorers shifted the balance of trade away from the Mediterranean to the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, Venice lost its dominance of the merchant routes to the East. After Napoleon abolished the Republic in 1797, the once-proud city went into a prolonged decline. Today, tourism buoys the economy, and a project to save the sinking city from flooding, under discussion for at least 40 years, may finally be getting underway.

Carboni is quick to point out that the key to the pragmatic Venetians’ trading success was that they never regarded themselves as superior. “Muslims were understood simply as figures in the wider world with whom it was necessary to do business,” he says. “Also, the Venetians were far more tolerant from the religious point of view than the rest of Europe.”

For centuries, the Christian Republic carried on a diplomatic high-wire act, balancing competing allegiances to Muslim rulers and the Catholic Church, essentially doing whatever was necessary to keep commerce as free and unhindered as possible. Even during the Crusades, the Venetians continued trading with Islamic partners. The Fourth Crusade, in fact, famously turned into an opportunity for Venice to attack the Byzantine empire, not Muslims. After the sack of Christian Constantinople in 1204, Venetians brought back incalculable treasures, including the four bronze horses now in the basilica museum. (The ones on the roof are copies.) From time to time, the Vatican placed restrictions on trade with Muslims. But the Venetians, eager to assert their independence from papal authority, circumvented the bans by trading surreptitiously through Cyprus and Crete.

The Mamluks, who ruled a vast stretch of territory from Egypt to Syria from 1250 till 1517, relied on the Venetian navy to protect their coasts, according to Deborah Howard. Although diplomatic relations were generally warm, the sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri personally placed chains on vice-consul Pietro Zen in 1511 and imprisoned him in Cairo for holding secret talks with Shah Ismael, the first Safavid ruler of Persia. The Venetians were seeking a Persian alliance to contain the expanding Ottoman empire, which did indeed end Mamluk power six years later, in 1517.

Carboni acknowledges that Venetians had a “love-hate relationship” with the Ottomans, who, unlike the land-locked Mamluks, nurtured aspirations to usurp Venetian control of the eastern Mediterranean. Despite several bitterly fought conflicts—notably over Corfu in 1537, Cyprus in 1571, Candia (Crete) from 1646 till 1669 and Morea between 1684 and 1716)—overall there were many more years of peaceful trading than war, he says, and it was Napoleon, not the Ottomans, who finally conquered Venice in 1797.

Like the ambitious French emperor, the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II, who conquered Constantinople in 1453, had a hunger for world recognition. “He wanted to be acknowledged by the European powers as the equal of emperors and kings,” says Carboni. To spread his fame, Mehmet requested that the Venetian government send an artist to immortalize him in portraits and a sculptor to forge medallions with his image.

|

| MUSEO CORRER, VENICE / CAMERAPHOTO ARTE VENEZIA / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| An unknown painter of the Italian school created this view looking down over the busy Constantinople harbor. |

The Venetians thought it would be in their interest to please the conqueror of Constantinople, so they selected Gentile Bellini, the most prominent painter of the time, and sent him off in 1479. In the nearly two years he resided at the Ottoman court, Bellini painted numerous portraits that ultimately left their marks on local artists and miniaturist painters in Istanbul and as far away as Isfahan and Tabriz. Mehmet’s publicity campaign succeeded beyond his dreams. The Bellini portraits have spawned so many copies on everything from book covers and posters to banknotes, stamps and comic books that, according to the Turkish Nobel Prize–winning author Orhan Pamuk, “any educated Turk must have seen them hundreds, even thousands, of times.” They embody the iconic image of an Ottoman sultan “the way Che Guevara’s portrait incarnates that of a revolutionary,”

|

| RUTH SCHACHT / STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN / BILDARCHIV PREUSSISCHER KULTURBESITZ / ART RESOURCE |

| Venice, as rendered by Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis in his Kitab-i Bahriye, a book of portolan charts and sailing directions produced in the early 16th century. |

Pamuk observes in the French magazine Connaissance des Arts. After Mehmet’s death, his son and successor, Bayezid II, who warred with the Venetians over their southern Greek territory of Morea, sold Bellini’s portraits in the Istanbul bazaar to help finance the construction of a mosque complex.

When it came to Muslim artists and craftsmen settling in Venice, however, the locals wanted to limit the competition; they allowed in very few artisans. Instead, the city imported impressive quantities of luxury goods made overseas, including Mamluk and Persian carpets, Syrian and Egyptian glass, Iznik porcelain and incised metal bowls and ewers from Syria.

From Venice, carpets were sold throughout Europe. Cardinal Wolsey, first minister to the English King Henry VIII, was “a pathological carpet collector,” who pressured diplomats to give him dozens as gifts, says Denny. Venetians bought raw silk from the shores of the Caspian Sea in northern Persia, manufactured elegant velvet caftans with Ottoman-style floral designs and sold them in Constantinople and elsewhere in the Muslim world. To combat the Venetian monopoly on luxury textiles, the 16th-century Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha promoted new techniques to produce silk brocades and velvets that are “among the supreme artistic achievements of Ottoman art,” according to Denny.

Ultimately, the development of the pedal-powered loom and spinning wheel in Europe led to the export of so much cheap cloth that it constituted what one economist called an early example of product dumping in Islamic markets. In the 15th century, Cairo historian Taqi al-Din al-Maqrizi exhorted Muslims to abandon low-quality European fabrics and wear local clothing instead.

A similar give-and-take process occurred in glass production. Recognizing that the glassmakers of Syria and Egypt had no serious rivals in Europe, the Venetians began importing raw glass, as well as broken glass (cullet) and plant soda ash from the Levant around the 13th century to copy Muslim designs at home. So successful was the transfer that certain enameled and gilt beakers, decorated with camels and desert plants and once believed to have originated in Syria, turned out to be Venetian-made. By the middle of the 15th century, Venetian glassmakers had perfected a technique to produce cristallo glass, a clear, colorless creation, free of defects, that successfully imitated expensive rock crystal. Ottoman artisans soon adapted the technique in the manufacture of Iznik porcelain. Thus a process that had begun with Venetians borrowing styles and materials from Islamic craftsmen came full circle with Ottoman ceramists building on Venetian expertise.

As cargoes of carpets, glass, silks and porcelains filled the harbor, it was obvious how Venetian fortunes and spirits faced East. The sheer energy of the commerce driving the city was a spectacle and entertainment to behold. The scale of trade was staggering; the sight of countless ships coming and going was breathtaking. From his quayside house overlooking the Riva degli Schiavoni, the 14th-century poet Petrarch, on a three-month visit from Florence, marveled at ships the size of “floating mountains,” the square-rigged, round-hulled cogs that boasted five decks and a hold. Four centuries later, the 18th-century painter Canaletto found the harbor just as vibrant, filling his canvasses with dozens of ships at anchor and a forest of masts.

|

| NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

Above: In 1479, at the request of Ottoman sultan Mehmet II, Venice sent one of its most prominent painters, Gentile Bellini, to Constantinople for nearly two years to paint portraits of the sultan. Widely reproduced, these became both stylistically influential and iconic. (Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name is Red deals with the upheaval western painting caused in court circles.) Below: Eastern styles in turn influenced Bellini, as evidenced by his portrait of a seated Ottoman scribe, now in Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. |

|

| ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

Convoys of galleys, two-masted lateeners and cogs set sail for Constantinople, Alexandria, Tripoli and Beirut carrying wool, wood and metals. By the 15th-century, they were also laden with such manufactured goods as textiles, soap, paper and glass. In return, cotton, spices, dyes, aromatics and salt arrived from Syria and Egypt, and silk, slaves and furs from the Tartar regions of Central Asia.

“On board the ships were sailors, soldiers, merchants, as well as doctors, priests and master carpenters,” Concina explains. Trumpeters and bagpipers were on hand to herald arrivals into ports of call; some captains even had them announce mealtimes. A diary compiled in the 1440’s by the trumpeter Zorzi da Modon that is now in the British Library describes life aboard ship and includes musical notations for leading crew and passengers in songfests. The outward journey to Alexandria took around a month and the return trip against the wind at least six weeks, notes Howard. Pilgrim voyages to the Holy Land were far shorter, taking around three weeks each way.

The state-run mude system, an immense trading network lasting for nearly 200 years from the early 14th century to the early 16th century, dispatched armed convoys to destinations as far north as England and Flanders and as far east as the Black Sea, according to Concina.

Overseas, trading posts known as fondacos (funduqs, khans or wakalas in Arabic) served as home bases for Venetian merchants. First mentioned by Herodotus in the fifth century BC, these caravanserais eventually stretched from Spain to China and are illustrated in the Maqamat, a 13th-century compendium of travelers’ tales by Muhammad Ali al-Hariri. Constructed around a large square courtyard with a well, the two-or three-story structure had colonnaded arcades with storage rooms for goods and stables for pack animals on the ground floor and rooms for travelers on the upper levels.

Typically, the fondaco’s single great gate was locked at night, both to protect merchants from robbery and to keep close watch on them. Although most of the fondacos decayed or were destroyed long ago, Acre’s Khan al-Ifrani, with its huge Gothic arches, is one that still exists; it has been converted into private residences.

Over the centuries, Venetian enclaves expanded around the fondacos. In Constantinople, where the Venetian quarter was located near the spice market, the residents built three churches over the course of 400 years from the 11th to the 15th century. The former house of the bailo is now—still— the Istanbul residence of the Italian consul-general. In Trebizond on the Black Sea, the Venetians built a church, houses, warehouses, quay and loggia.

Despite treaties intended to protect them, the Venetians were occasionally held prisoner in their fondacos, and one 17th-century bailo was hanged in Istanbul. Instead of retaliating with sanctions, the Venetians continued business as usual. “The boundlessly cynical Venetians never let morality, religion or ideology get in the way of making money,” Romanelli dryly observes.

In contrast to the extensive Venetian settlements in cities of the Muslim world, there were no permanent Muslim embassies in Venice. Ambassadors generally came for brief annual stays ranging from several days to a few weeks, according to Maria Pia Pedani, a specialist on Ottoman history at the University of Venice. When Mamluk envoy Taghribidi arrived from Cairo with his retinue of 20 attendants for an unusual 10-month round of treaty negotiations in 1506 and 1507, he caused a sensation as he was escorted around the city by pages and macebearers. Taghribidi and other Muslim diplomats were housed on the Venetian island of Giudecca so they could be controlled and watched, says Pedani.

|

| MUSEO CORRER, VENICE / ERICH LESSING / ART RESOURCE |

| Venetian relations with the Ottoman Empire were sustained by trade, but punctuated by conflict. In the mid-17th century, the Turks retaliated against the Venetians for attacks on Turkish ships by the Knights Hospitaller of St. John, beginning a quarter-century of war. A Venetian painter depicted the “Action of August 27, 1661,” a battle in which the combined forces of Venice and Malta—22 ships—defeated a Turkish fleet of 36 galleys. |

Before the creation of a temporary funduq for Muslims in the late 16th century, merchants visiting Venice and a handful of artisans stayed at inns near the Rialto. But even when the Fondaco dei Turchi opened in 1621 in the Santa Croce quarter, across the Grand Canal from the Jewish ghetto, it housed fewer than 100 merchants, including Turks, Bosnians, Albanians and Persians. An imposing, three-story building with two tiers of colonnaded arcades surrounding an inner courtyard, the Fondaco dei Turchi had been modeled after Middle Eastern funduqs. Above the ground-floor warehouse were living rooms, a bath and a prayer room. Muslim visitors were free to come and go during the day, but were locked in at night. The former fondaco now houses the city’s natural history museum.

“We have accounts of Turks having coffee at the Piazza San Marco and exchanging news from Turkey,” Concina explains. “Despite frequent wars with the Ottomans, Turkish merchants were figures of respect.”

When I meet Giampiero Bellingeri, a leading authority on Venetian–Turkish relations from the University of Venice, at the 18th-century Caffé Florian, a landmark institution on St. Mark’s Square, the professor reminds me that the Caffé was modeled after coffee houses in Istanbul.

|

| MUSÉE DU LOUVRE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| A Mamluk governor, or na’ib, and his retinue prepare to receive Venetian consul Niccolò Malipiero in Damascus in 1511. The cupola of the Great Umayyad Mosque is in the background. |

“The Ottoman authorities banned cafés from time to time because they were seen as places where subversive ideas circulated,” he explains. “Poets exalted coffee as ‘the black angel’ that inspired them.”

While Venetians respected Turkish merchants, they could not admit that the Ottomans possessed a well-developed culture of their own. “It was only after the Ottomans were defeated at Vienna in 1683 that we could begin to acknowledge that the Turks were not barbarians and had produced literature and art of great finesse and profound reflection,” says Bellingeri. “Once the Ottomans ceased to be a military threat, we could begin seeing them as equals.”

And, occasionally, as objects for ridicule. Carlo Goldoni, the 18th-century Venetian playwright, wrote a number of works poking fun at Turks and Persians—yet mocking Venetians in equal measure. In “The Impresario of Izmir,” an unwitting Turk comes to Venice to organize an opera company and becomes so embroiled in the quarrels of backbiting divas and a nasty castrato that he returns home in frustration without a troupe.

Around the corner from the Florian,

|

| METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART |

| “Pilgrim flasks,” originally made of metal or leather, evolved into mostly decorative objects in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. This example is decorated with vaguely vegetal patterns in gilt and enamel. A significant portion of the Venetian economy was fueled by Christian pilgrims, who embarked for the Holy Land from Venice. |

Bellingeri takes me to the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana to inspect a masterpiece of Venetian forgery. Inside the library, we slip quietly past scholars poring over books and manuscripts at long tables and enter a back room where the so-called “mappamundo,” the 1559–1560 map of the world created for the Ottoman market, is displayed on one wall. In the center of the map, intricately detailed drawings of western and eastern hemispheres are joined in the shape of a heart, surrounded by cramped scrawls of miniscule Ottoman script that describe cities, states and empires of the known world.

The text purports to have been written by “poor, powerless, indigent Hajji Ahmed from Tunis,” says Bellingeri. He allegedly studied in Fez and was captured by “the Franks,” but allowed to continue practicing his religion. In compiling the map, Ahmed explains that he consulted Socrates, Plato and Abu al-Fida, the last a Syrian geographer-prince who lived from 1273 to 1331 and was greatly respected by Venetian scholars, Bellingeri explains.

Where did the mapmaker live, I ask.

“Good question,” the professor replies. “He never says, and for good reason. In fact, Ahmed was a fictional creation by the Venetian scholars who made the map. They thought that having a Muslim author would make it sell better in Islamic lands, but their ruse didn’t work.”

It certainly couldn’t have helped the map’s authenticity that the true authors made several glaring errors. “When my colleague, the late Giorgio Vercellin, and I saw mistakes in writing the words Islam and Allah, we figured the authors had to be Venetian, not Muslim,” says Bellingeri with a wry grin. Even though there’s no proof, the professor is positive the forged map was a collaboration by Giovanni Battista Ramusio, a noted cosmographer and naval historian, and Michel Membré, a former ambassador to Persia and the Republic’s senior dragoman, or interpreter.

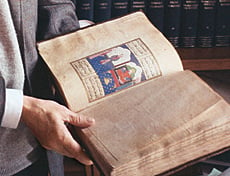

Apart from the counterfeit map, the Biblioteca Marciana contains one of the most extensive collections of Islamic manuscripts, incunabula and later printed books in the world. The day after meeting Bellingeri, I have an appointment with Marino Zorzi, the library director, to view a remarkable pair of books. One, the Iskandarnama or Book of Alexander, is an illustrated manuscript dated 1430 from Edirne, the Ottoman capital before Mehmet II conquered Constantinople; the other, Diverse Dressing Habits of the Turks, is a 17th-century volume devoted to Ottoman clothing.

Inside his corner office across from the Doge’s Palace, Zorzi is obliged to partially close the heavy wooden shutters to block out the dazzling sunlight and his breathtaking view across the water to the Palladian church of San Giorgio Maggiore. Pushing aside exhibition catalogues and books scattered on an enormous table, the director makes room to pore over the two books.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Above: Scholar Giampiero Bellingeri points to the “Hajji Ahmed” world map that he believes was actually produced by Venetian cartographers for sale in the Ottoman Empire. The Muslim pseudonym would have given the map greater credibility. Below: This copy of the Qur’an was printed in Venice by Paganino and Alessandro Paganini, using moveable type, in 1537—the first-ever printed Arabic edition. Venice was a center of typography and printing technology, and also of the commercialization of book- and map-printing. The Paganini Qur’an was not a commercial success, however, for both religious and practical reasons. |

|

| SAN MICHELE IN ISOLA / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

“The Iskandarnama is probably the most important Islamic work of art in Venice today,” Zorzi explains. “It’s one of the few illustrated manuscripts we have from the Ottoman empire.”

Acquired by the library in 1797 as part of an extensive collection of Greek manuscripts, Arabic and Islamic books, coins and objects donated by Giacomo Nani, Venice’s chief superintendent of naval affairs, the Iskandarnama is a curious East-meets-West cultural grab-bag. It contains not merely the highly embellished exploits of a legendary Muslim version of Alexander the Great, but also an account of the Prophet Muhammad’s journey to heaven, episodes from the Persian Book of Kings, or Shahnama, the signs of the zodiac and the planets as well as conversations between the book’s poet-author Taj al-Din Ibrahim ibn Khidr Ahmadi and a friend.

The costume book, donated to the library by the patrician bibliophile Giralamo Contarini in 1843, could not be more different. Bound in inexpensive cardboard and about the size of a trade paperback, this popular edition was published in Istanbul but features Italian captions, indicating it was published for export. It presents a cross-section of Ottoman society with 62 realistic portraits of individuals characterized by the vividly colored clothes they wear.

The turbaned sultan Bayezid I, “the Thunderbolt,” strikes an unusually meditative pose in a blue robe and sleeveless purple tunic. Regally attired in a dark pink tunic dress with gold belt and brocaded cape, the unnamed wife of a sultan sports red lipstick, painted eyebrows and a crown surmounted by a broad fan. There’s a court page in a long orange caftan and domed hat, a head gardener all in green, a hunter with rifle, horn, axe and plumed hat. On one page, a barefoot Hindu pilgrim with a wispy beard and fringed cape carries a stick to support him on his begging rounds; another illustration shows a sword-bearing soldier with a leopard skin slung around his shoulders and a human head dangling from his belt. In addition to the court treasurer in sober brown caftan and a pair of eunuch harem guards, there’s also a jaunty idyll of three women in a rowboat.

As modest as the Iskandarnama is opulent, the costume book strikes me as yet one more means through which the Venetians were bent on acquiring knowledge, culture and wealth from the Islamic world. Collectors like Contarini and Nani, mapmakers like Ramusio and Membré, explorers and diplomats like Marco Polo and the Zen family, all depended on Muslim trade to make their fortunes. As Zorzi reopens the shutters on one of the world’s most glorious perspectives, with black gondolas bobbing in the silvery water, I wonder how much of this image would have remained a mirage without the matchless Venetian ambition to embrace the risks and possibilities of trading goods and ideas with the strangers of the East.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Above: The Doge’s Palace incorporates such Islamic motifs as the decorative merlons atop its façade. Below: The coffee shop came to Venice from Istanbul, and the Caffé Florian, still open in St. Mark’s Square, was the first. |

|

| JOE MURADOR / GRAND TOUR / CORBIS |

Tracking down Islamic influences and Muslim connections in Venice is not hard if you know where—and how—to look. If you stand on the square in front of St. Mark’s Basilica, signs are all around. To the right is the Doge’s Palace with its distinctive three-tiered merlons, modeled on crenellations on Cairo’s Ibn Tulun Mosque. To the left is the Torre dell’Orologio, the 1498 clock tower with a giant blue zodiac dial identical to the clock face in al-Ghazari’s 13th-century treatise on robots. (Twelfth-century historian Ibn Jubayr mentions a similar clock with descending weights at the Great Mosque in Damascus.) At your back is the Caffé Florian, an 18th-century institution patterned after coffee houses in Istanbul. Straight ahead, the tall cupolas of the basilica resemble mosque domes in Cairo’s City of the Dead and across the Arab world. Stone window grilles resemble the decorative tracery abundant in Muslim religious architecture. On the basilica’s facade is a glittering 13th-century gold mosaic depicting the theft of St. Mark’s body from Alexandria in 828. Venetians built the first church, a precursor to the present 11th-century basilica, to house the saint’s relics. Inside the basilica’s atrium, Biblical mosaics with scenes of banquets, bedside miracles and camels traversing deserts were modeled on similar scenes in illustrated Arabic texts such as al-Hariri’s Maqamat and the Persian epic, the Shahnama, according to Cambridge University architectural historian Deborah Howard.

Within the main sanctuary, which is covered floor to roof with opulent mosaics, the entrance to the treasury is surmounted by a pointed arch with a Fatimid-style relief of peacocks and the gap-toothed decorative border called billet molding, common in Jerusalem and other cities of the Levant. The treasury itself showcases stunning Arab pieces, including a rock-crystal ewer that belonged to the 10th-century Fatimid caliph al-‘Aziz, a 10th-century Abbasid glass bowl carved with lions and a delicately beautiful, silver gilt and niello casket incised by Arab craftsmen in 12th-century Sicily with images of women playing a lute and a harp.

Upstairs in the basilica museum are five 16th-century gold-and-silver brocaded carpets from Isfahan. Another well-preserved Persian carpet measuring 150 by 275 centimeters (5' x 9') is woven with ducks and flowers surrounding bright blue, interlacing designs in the center. A third carpet was donated by the Safavid Shah Abbas I in the 16th century, with instructions that it be used to present items from the basilica’s treasury during religious celebrations.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

| A mosaic in the Basilica San Marco depicts customs officials in Alexandria repulsed by the pork that hid the purloined remains of St. Mark. |

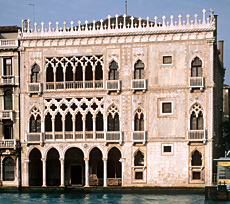

Next to the basilica, the 14th-century Doge’s Palace is completely without fortification, virtually unique for the time in Europe. Instead, the two levels of colonnaded arches make for a blessedly open and airy ground floor and second-story loggia. Howard maintains that the Venetian envoy Nicolo Zen brought home this bold architectural plan after his 1344 visit to Cairo, where he saw the Iwan al-Kabir, the official hall of justice, and the Citadel Mosque of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad. The exterior design of the Doge’s Palace bears a striking resemblance to both buildings.

Upstairs inside the Doge’s Palace, the walls of the Shields Room, where visiting envoys gathered, are covered with giant, vividly colored maps of the Mediterranean, Italy and Arabia. They were drawn by 16th-century geographer Giovanni Battista Ramusio, who used numerous Muslim sources, including maps by the 13th-century prince Abu al-Fida. In a nearby room, the Sala della Quattri Porte, is Gabriel Caliari’s 1603 painting of Doge Mario Grimani flanked by turbaned emissaries from Shah Abbas I, dressed in blue and white silk. In the foreground, black-robed Venetians admire a magnificent cloak, velvet brocade and a silk rug threaded with gold, perhaps the very one that’s in the basilica museum.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

| Beckoning mariners from Venice’s eastern tip, the campanile of the Basilica of San Pietro Castello was built to resemble Alexandria’s Pharos lighthouse. |

While this painting delivers a pointed lesson on the benefits of diplomacy, the vast murals in the Sala del Scrutinio, dramatizing the murderous chaos of the naval Battle of Lepanto and other Venetian victories, are reminders that the peace-loving Serenissima could fight when provoked. Elsewhere in the palace are various spoils of war: an enormous red Ottoman banner, gorgeous ships’ lanterns bearing crescent moons and tughs or standards, two-meter (7') poles decorated with horse tails. The more tails, the higher one’s rank in the Turkish court; the sultan had seven.

Across the Grand Canal from the San Marco quarter, the Accademia gallery concentrates a number of masterpieces with Muslim references. In Giovanni Mansueti’s painting of scenes from the life of St. Mark, Mamluk figures wearing conical red zamt hats and the white “horned” judicial turbans crowd an Alexandrian cityscape that evokes Venetian architecture. In a Tintoretto painting from between 1562 and 1566, St. Mark reaches down from the heavens to lift up a drowning Saracen sailor. In Gentile Bellini’s detailed account of a religious procession through St. Mark’s Square, housewives proudly drape Turkish carpets from balconies lining the north side of the piazza. In Paris Bordone’s 1534 painting of a fisherman returning the doge’s ring, Andrea Gritti, the Venetian chief of state from 1522 to 1538, is enthroned on a western Anatolian “star ushak” carpet with red, green and gold arabesque designs.

Back outside, simply wandering the streets is an education in Islamic influence on Venetian architecture. Christopher Wren, the 17th-century architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, wrote about Islamic elements in Gothic art and architecture—from ogive windows to the resemblance of flanking church towers to minarets. John Ruskin, the 19th-century art critic and philosopher, went even further, arguing in The Stones of Venice and other works that much of Venice was directly copied from the Near and Middle East.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Leading private homes often incorporated architecture from Islamic lands, including the Ca’ d’Oro with its pinnacles and, below, the Palazzo Dario with its “telephone-dial” decoration. |

|

| JULIE WOODHOUSE / ALAMY |

Cambridge scholar Deborah Howard maintains that the city’s labyrinth of streets, patios and secret gardens, and its saturated colors and ornamentation, were inspired by Muslim urban design. Venetian palazzos—with their inner courtyards surrounding underground cisterns, winding open staircases, flat-roofed terraces and balcony verandas that resemble mashrabiyyah windows—imitate floor plans in the Levant, she says. Exterior windows are based on scale models of mihrabs—prayer niches—brought back from the East.

Impressed by Islamic architecture, Venetian merchants wanted to adapt elements of the style at home, partially for esthetic reasons and partially to advertise their trading success. Two of the more striking Muslim-influenced palaces are the Ca’ Dario and the Ca’ d’Oro. On a mission to Cairo, 15th-century diplomat Giovanni Dario so admired Amir Bashtak al-Nasiri’s magnificent palace that he incorporated its distinctive “telephone-dial” motif in marble decorations for his own palace, down the Grand Canal from the Accademia. On the opposite side of the serpentine Grand Canal past the Rialto bridge, the Ca’ d’Oro is one of the most lavishly decorated palaces in the city, with its ogive windows, cream-colored Gothic tracery and Egyptian-style pinnacles. Originally, the façade was painted in gold leaf and ultramarine like the interior of a Persian palace, says Howard. The Ca’ d’Oro now houses a museum of paintings, sculpture and furniture, and contains a medallion portrait of Mehmet II by Bellini.

Walking from the Rialto back to St. Mark’s Square, I try to imagine what the shops were like in the 15th and 16th centuries, when storekeepers inflated prices to take advantage of visiting eastern dignitaries and merchants. Glass, silk and tapestries are still on sale, but nowadays, the boutiques are also filled with Furla bags and dresses, watches, sneakers, gianduja chocolates and La Perla lingerie. Chinese immigrants sell me a souvenir bag printed with a painting of St. Mark’s Square.

Inside the Correr Museum at the opposite end of the square from the basilica, I have a look at Jacopo de Barbari’s panoramic 1500 map of Venice, showing dozens of ships jostling for space in the harbor.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

| The back of the so-called “Throne of St. Peter” is inscribed in Arabic. |

These days, instead of the round-bellied cogs in de Barbari’s map, the waterside Riva degli Schiavoni is lined with water buses, called vaporetti, car ferries and cruise ships. A two-story ocher-brown building with Mamluk crenellations midway up its façade was a 15th-century bakery that produced long-lasting ships’ biscuit for voyagers. Nearby were houses for pilgrims awaiting departure for the Holy Land.

Across a small bridge, the Naval History Museum displays elaborately carved side panels from wooden galleys, the figure of a Turkish prisoner from the stern of a warship, large models of galleons, triremes and galleys, and a full-sized boat rigged like a Nile felucca.

Up the broad Via Garibaldi with its working-class cafés and shops, I make my way to the Basilica of San Pietro Castello, the city’s principal cathedral until 1807, when the Basilica of St. Mark’s became Venice’s primary church. An immaculately white stone campanile rises from the grassy park surrounding the basilica. Constructed from 1482 to 1488 by Mario Codussi, the bell tower was erected at the eastern tip of the city as a Venetian version of Alexandria’s Pharos lighthouse. Inside the magnificent cathedral is the so-called “Throne of St. Peter,” donated by the Byzantines to thank Venice for its help wresting Sicily from the Arabs in the 13th century. In fact, it is not a throne at all, but a stone chair with a back fashioned from a 12th-century Islamic funerary stele inscribed with Qur’anic verses around a six-pointed star.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Above: A copy of The Alexander Romance, acquired in 1430 from Edirne, now in the Biblioteca Marciana. Below: An iron-nosed statue of a trader is said to be a portrait of one of the Mastelli brothers. |

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Elsewhere, Near and Middle Eastern references pop up in unexpected places across the city. At a museum of Greek icons next to the church of San Giorgio dei Greci, I stumble across a page from a 14th-century copy of The Alexander Romance with Arabic writing in the margins. Nearby, at the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, paintings by Vittore Carpaccio from the early 16th century portray Mamluk musicians and judges against Near Eastern backdrops as St. George slays a dragon and baptizes converts. On the wide square in front of the church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, schoolchildren play noisy games of soccer and tag in front of 1489–1490 stone panels by Tullio Lombardo, one representing St. Mark healing the cobbler Anianus in Alexandria, the other of the evangelist baptizing him. In one of those historical juxtapositions peculiar to Venice, I find myself seeking out the first printed copy of the Qur’an at the church of San Francesco della Vigna. Legend has it that St. Francis embarked from the site in the 13th century, on his way to Egypt to try to convert the sultan.

Out in the Cannaregio district, about as far north as you can get in the main city without swimming, lies a Moorish mystery—four statues of Muslims in the Campo dei Mori. This theatrical quartet, “dressed up like characters from the cast of a comic opera,” as Howard writes, probably once graced the nearby Palazzo Camello, which still sports a charming stone frieze of a turbaned man gazing up at a camel with a bulky pack strapped to its back. The most prominent of the figures leans awkwardly in his niche next to the birthplace of 16th-century artist Jacopo Robusti, or Tintoretto. The poor fellow is weighed down by an outsized turban, probably added a century or more after the image was originally carved in the late 13th or early 14th century. Some historians once thought that the stone “moors” belonged to a fondaco created for Arab merchants, but Howard disagrees, speculating that the statues may have something to do with the Moro family and its role in the spice trade. No one really knows.

And I like it that way. In a city where the minutiae of the past have been pored over for centuries, it’s reassuring that some links of the Republic’s DNA, and aspects of its East–West trade in particular, remain a question mark for future generations of scholars.

Move over Marco Polo. The massive, 58-volume diary by Marin Sanudo the Younger, a 16th-century Venetian senator equipped with unparalleled access to the Republic’s secrets and a refreshing candor, is an unsurpassed account of life at home and abroad during the city’s heyday. Unlike the peripatetic Polo, who spent a quarter of a century on the road, Sanudo stayed put, letting the East come to him, recording the activities of Muslim envoys in Venice and anecdotes by Venetian merchants returning from overseas. A political insider with a well-honed esthetic sensibility, he writes of the Persian envoy Ali Bey showing off magnificent decorated leather boxes and launching a fad for reproductions of them in Venice. He reveals that the Senate pretended a narwhal horn had been stolen from St. Mark’s Treasury rather than admit that the potent amulet, reputed to detect poison, had been offered as a secret gift to Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. When news arrives that the Ottomans defeated the Safavids at the 1514 battle of Çaldiran, Sanudo dryly notes that “we know through the grapevine that the Ottomans got the short end of the stick,” despite their victory.

“He was a very witty observer, detailing important meetings in the Ducal Palace and commenting on secret documents in the archives,” explains Stefano Carboni, curator of the 2007 exhibition “Venice and the Islamic World” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was not until the early 20th century that the diaries were published in full. “Because he wrote in Venetian dialect, translating them will be a huge enterprise,” says Carboni, but they represent an invaluable and largely untapped wealth of information about East–West trade and the period when Venetian artisans were busy creating a vogue for Islamic-style textiles, inlaid metalwork, lacquered wood, enameled glass and other crafts.

Venice’s link to the East has produced an extraordinary wealth of literature, philosophy and travelogue. In the 13th century, Polo recounted the sack of Baghdad, the “villainy” of Isfahan and the pearls and spices of Hormuz en route to Cathay. The maritime republic became a conduit for ancient Greek dialectics and Islamic discoveries in astronomy, mathematics and medicine. Between the 14th and the 17th centuries in particular, Venice was “an island of relative intellectual freedom,” according to Michael Barry, a curator in the Islamic art department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and lecturer in Near Eastern studies at Princeton University.

After the reconquest of much of Muslim Spain in the 13th century, the University of Padua (a city that was annexed to Venice around the same time) became the chief European center for the study of Ibn Rushd (Averroës) and his interpretations of Aristotle. Dante himself turned to the 12th-century Andalusian scholar to make sense of the Greek philosopher’s difficult teachings. Ibn Rushd’s speculations on the predominance of reason over faith had profound effects on the evolution of religious doctrine in the West, prompting the 13th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas to repudiate Ibn Rushd as “a corrupter of Aristotelian philosophy.”

In Europe’s centuries-long assimilation of Islamic science, a 1521 Latin translation of The Canon, the medical reference text by Persian doctor Ibn Sina (Avicenna), who lived from 980 to 1037, supplanted Gerard of Sabloneta’s 13th-century edition and spread throughout Europe.

The influence of Arab philosophy and science persisted longer in Venice than most other cities in Europe. Fresh editions of Ibn Sina’s writings were being published in Latin as late as the 16th century and The Canon was still part of the curriculum at the University of Padua until the 17th century, Barry observes.

One of the earliest and most ardent observers of Islamic influence on Venice was the 19th-century English art critic John Ruskin. “The Venetians deserve especial note as the only European people who appear to have sympathized to the full with the great instinct of the Eastern races,” Ruskin declared in his masterpiece, The Stones of Venice, a three-volume paean to the city published from 1851 to 1853. With thoroughgoing and often lyrical analysis of arabesque ornamentation, pointed windows and arches, ornate molding and other architectural details, Ruskin outlined the transition of Venice from a Byzantine city to one that borrowed heavily from Islamic models. In a poetic rumination on the ways the city mimicked the patterns of nature, he claimed that even the flowing curves of Veneto–Moorish architectural decoration echoed the design of a galley’s hull and the swirl of waves along it.

European novelists fell in love with the city partly for its exotic Muslim elements, popularizing the image of Venice as a romantic mirage, an escapist hold-out against the belching smokestacks and dehumanizing mass production of the industrial age. The 19th-century French novelist Emile Zola famously claimed that “the Orient begins in the Merceria [of Venice], with its streets so narrow,” and Charles Dickens said the city evoked The Thousand and One Nights. “Opium couldn't build such a place, and enchantment couldn't shadow it forth in a vision,” the English novelist wrote in a 1844 letter to his friend and biographer, John Forster. Marcel Proust made numerous Moorish allusions in Venetian scenes in his seven-volume, fictional opus Remembrance of Things Past. In The Sweet Cheat Gone, the sixth novel of the series, he wrote, “My gondola followed the course of the small canals, like the mysterious hand of a Genie leading through the maze of this oriental city,”… passing “tall houses with their tiny Moorish windows.”

Other authors draw inspiration from Venice for works that take place in the East. Set in 16th-century Istanbul, My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk, the recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize for Literature, is a mystery about the murders of a pair of court artists commissioned by the sultan to create Venetian-style illustrations for a book intended to glorify his reign. Apart from the crime and a romantic subplot, the novel reflects on the tension between Islamic and western traditions in art.

|

Paris-based author Richard Covington writes about culture, history and science for Smithsonian, The International Herald Tribune, U.S. News & World Report and The Sunday Times of London. His e-mail is richardpeacecovington@gmail.com. |