Written by Cloe Medina Erickson

Written by Cloe Medina Erickson

Photographed by Kristoffer Erickson

Video by

Cloe Medina and Kristoffer Erickson

e didn’t wake up until five today,” says Sa‘id Mas’udi, shielding his eyes from the scorching mid-morning sun and the full day of work that lies ahead. It is the 23rd day of Ramadan, the Islamic lunar month when Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset. Overtired by the short nights demanded by their religious duty and the work of running a seasonal guesthouse, Mas’udi and his family slept through suhur, the pre-dawn Ramadan meal. Now they must wait until sunset to eat or drink again.

e didn’t wake up until five today,” says Sa‘id Mas’udi, shielding his eyes from the scorching mid-morning sun and the full day of work that lies ahead. It is the 23rd day of Ramadan, the Islamic lunar month when Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset. Overtired by the short nights demanded by their religious duty and the work of running a seasonal guesthouse, Mas’udi and his family slept through suhur, the pre-dawn Ramadan meal. Now they must wait until sunset to eat or drink again.

Mas’udi’s modest home of mud and stacked stone in the remote village of Taghia, Morocco—a three-hour walk from the nearest road— is bursting with the activity and noise of arriving and departing travelers. Tents are packed and unpacked, donkeys are loaded and unloaded, routes for the day’s journeys are discussed and Fatima, Mas’udi’s wife, bakes loaf after loaf of bread to feed their guests.

The roadless Zawiya Ahansal region of Morocco’s central High Atlas Mountains is named after Sidi Sa‘id Ahansal, a local 14th-century religious teacher believed to be a descendant of King Idris I of Morocco and the Prophet Muhammad.

It has been a crossroads for travelers and a place of seasonal migration for centuries. The historic trade route from Timbuktu to Marrakesh passes over the rugged plateaus and deep limestone gorges that dominate the landscape, crossing eastward from the Atlantic plains over the Atlas and into the Sahara.

With an elevation above 2000 meters (6500'), the plateaus are covered in deep snow in the winter, leaving only the gorges with their springs, forests and irrigable land capable of supporting permanent habitation.

|

Above: Author and climber Cloe Medina Erickson visits with local residents in Taghia. Below: The centuries-old Monday market in Zawiya Ahansal draws the local Ihansalen and seasonal nomads to trade. |

|

In the summer, however, the snow melts to reveal fertile pastures, an irresistible invitation to the nomadic pastoralists who spend their winters in the desert regions south of the Atlas.

They arrive in the spring and the fall instead of the summer, drawn by the towering limestone walls rather than the fertile plateaus.

This year the climbing migration coincides with Ramadan, and two unique cultures find themselves at a fragile tipping point. The permanent inhabitants—Berbers, or Ihansalen, as they are referred to locally—and the foreign climbers now face the same challenge their ancestors and predecessors have faced for centuries: Finding a sustainable balance between tradition and outside influence.

Mas’udi wears the exhaustion of this challenge on his face; we hear him replace the typically optimistic Ihansalen response—“ma feish mushkila,” meaning “No problem”—with “mushkila shwiya,” “It’s a small problem.”

Serious rock climbers live a migratory existence. They travel the world, following seasons and weather patterns, always searching for destinations with untapped climbing potential. Over the past decade, Zawiya Ahansal has become one such destination.

Ernest Gellner, an English social anthropologist who spent time in the region during the 1950’s and ’60’s, foreshadowed its imminent rise in popularity among travelers in his book Saints of the Atlas: “The environment is favourable, indeed charming. Sidi Sa‘id Ahansal had chosen his place well, and it is in my view destined, when roads become adequate and the rise of national income in Morocco creates the demand, one of the favoured tourist centres in the Atlas.”

For French professional climbers Arnaud Petit and Stephanie Bodet, the mountains of Zawiya Ahansal are comparable to the most famous in the world. They first visited the region in 2002. Now, they return every year.

|

| Students help construct rafters for the roof of their new school. All the building materials for the school, a collaborative effort by local residents and American climbers, were brought to the village on donkeyback. |

“The climbing is world class. There are very few places in the world with such a concentration of untapped climbing potential and such high limestone walls,” says Petit. “It is possible to equip a sustained route with more than 15 pitches (600 meters). That is incredible.”

Establishing climbing routes on limestone—“equipping” the route—requires the placement in the rock of permanent anchors, usually 8- to 12-centimeter bolts (3–5"), with a drill.

A “pitch” is the climb from one such “belay point” to the next, typically 30 to 60 meters (100–200'). The climbers who establish the routes must possess optimum strength, endurance and mental focus, but even so, it can take up to a month for a group of four experienced climbers to equip a 600-meter (2000') route. Once permanent anchors are in place, others can climb the route.

Word of the solid, continuous stone in Zawiya Ahansal has spread quickly through the world climbing community, and each season sees more and more climbers. In the last four years, the number of climbers visiting the area—most of them Europeans—has grown from 20 to over 400 in the fall season alone, a significant number in a region of only a few thousand local inhabitants.

“The combination of dry weather, excellent rock, hospitable people and an adventurous setting creates the perfect conditions for a rock-climbing holiday,” says Conrad Anker, an athlete for The North Face and one of the premier climbers in the world. He visited the region in 2006 and understands the rapid growth in its popularity.

“The vertical nature of the cliffs ensures that the climbs that are established are difficult. Hence, top climbers want to come and test their mettle,” says Anker.

With popularity comes pressure. Luckily, the Ihansalen have a history of negotiating sustainable relationships with their neighbors: Their land use agreement with the Ait ‘Atta, the largest and most dominant nomadic tribe between the Atlas and the Sahara, has weathered nearly 1000 years. Under its terms, the Ihansalen allow the Ait ‘Atta free passage to the high pastures during the summer, ensuring the survival of their flocks. In return, the Ait ‘Atta provide security to the Ihansalen from other, potentially dangerous, tribes passing through the region; both groups benefit from the weekly market where they trade much needed merchandise with each other.

In the summer, the Ait ‘Atta greatly outnumber the Ihansalen, but their relationship has been maintained in large part thanks to the existence of “professional neutrals”—descendants of Sidi Sa‘id Ahansal—and their establishment of a center of sanctity, a religiously based trucial zone, in which they guarantee unimpeded trade and free passage to those with a shared interest in the territory.

|

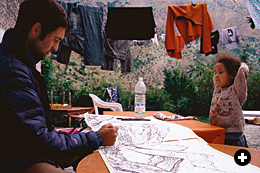

| Above: Conrad Anker organizes his gear at a belay point on “Baraka,” a climbing route on Mount Oujdad, a 2695-meter peak. Baraka means “blessing.” Below: Sa‘id and Fatima Mas’udi’s daughter, Rashida, watches climber Renan Öztürk as he sketches the landscape of her village from the guesthouse. She started school in Taghia in 2006. |

|

The influence of professional neutrals has diminished over the last century with the establishment of Morocco’s centralized government, which now acts as a mediator among the tribes. However, rapid demographic change is encouraging the designation of new neutrals with some of the same characteristics as the old: a respected position in both groups and, perhaps more important, literacy. Thus a familiar mechanism, naturally taking shape between the Ihansalen and the European climbers, may ensure a similarly sustainable and mutually beneficial relationship for their future.

Mas’udi and Yusuf Rizki, Taghia’s other guesthouse owner, have a working knowledge of French and Arabic, a characteristic that has marked them for this “neutral” role. However, the end of Ramadan sharpens the cultural differences between the climbers and the Ihansalen and increases the burden on the two men and their families: Taking care of guests means sacrificing sleep and time together during a holiday. In addition, as always, there are the risks of exposing their sons and daughters to the westerners’ foreign lifestyle.

“It is very difficult for me to prepare food all day,” says Fatima on the laborious task of feeding a house full of foreigners during Ramadan. “They eat in front of us. Especially today: We slept through suhur and must wait hours to eat.” During his travels, Anker has observed firsthand that the tourists’ values can create conflict, and even such supposedly simple items as clothing and food have deep cultural signification that can be misunderstood.

“The biggest challenge facing mountain communities is the influx of tourists, their money, their values and their demands on the infrastructure,” says Anker. “The money, in general, has a positive effect, as people are paid for their services and goods, and the multiplier effect spreads it through the community. In fact, tourism is a fine way of moving some of the accumulated wealth of the industrialized nations to countries that are rich mainly in scenic resources.”

For now, the families’ sacrifices are outweighed by the benefits of cash in a previously subsistence economy. With the money earned from their seasonal hospitality, Mas’udi and Rizki have begun to improve the Ihansalen way of life and provide their children with increased opportunities through education.

In 2006, Mas’udi and a group of The North Face climbers spearheaded a community development project that restored Taghia’s school and a network of mountain trails. This collaboration helped strengthen ties between the two cultures.

“The responsibility to create a sustainable relationship rests with the visitors. They are the guests—they have come there of their own volition,” says Anker. “Treating the local people with respect and courtesy, being mindful of cultural mores and being grateful go a long way toward creating a mutually beneficial relationship.”

Rizki sees providing educational opportunities to the children as a personal obligation, especially now with the foreign influence. “The children see them [the climbers] and their material goods and they do not understand the differences,” says Rizki. “But at some level they do understand, and it makes their life much harder to accept.”

Rizki sees providing educational opportunities to the children as a personal obligation, especially now with the foreign influence. “The children see them [the climbers] and their material goods and they do not understand the differences,” says Rizki. “But at some level they do understand, and it makes their life much harder to accept.”

Rizki donated land for a preschool for the village’s children and began construction on it. “Our children are so far behind compared to other Moroccans,” he says. “When they begin grade six, many of them still cannot read or write, and then they just continue to fall further behind.”

The preschool’s curriculum will focus on religion and the Arabic and French alphabets. Rizki hopes the school, operated on donations, will supplement public education, giving the local children the boost they need to match their peers.

|

Above: Youngsters attend class in Taghia’s school, refurbished as a cooperative project by village families and The North Face climbers. Below: Sa‘id and Fatima Mas‘udi load their donkey for the weekly trip to Zawiya Ahansal’s market, a three-hour walk from Taghia. |

|

Bodet has witnessed change in the children’s aspirations since her first visit to Taghia five years ago.

“The youth of Taghia dream about the western way of life. It seems that they want to be connected with the world. It would be egotistic to wish to maintain people in their traditional way of life, especially the women, who live a very hard life in these mountains. If the effect of tourism can be to bring more women to school, it will be a great change,” says Bodet.

As history shows, relationships in this extreme and varied land must be mutually beneficial in order to last. Like the Ihansalen and the Ait ‘Atta, the climbers and the Ihansalen are finding something in each other that they lack in their separate lives. New economic and educational doors are opening for the Ihansalen, leading to increased outside opportunities. In exchange, the foreigners experience unparalleled climbing opportunities and a unique culture in a region still beyond the limits of modern communications and transportation.

“We hope that they will come not only for the climbing, but for the culture also,” said Petit, who also hopes the visitors will be able to adapt to the place they are visiting. “Morocco is a Muslim country, and we have to respect the Moroccans’ traditions and religion in order to live peacefully together.”

Today the atmosphere at the guesthouse emphasizes the fragility and the uncertain outcome of this cultural balance. Mas’udi’s nephew Mahmud Jani passes his weary eyes over the climbers bustling in and out.

“Maybe by 2010 things will change and there will be more tourists in Taghia than residents,” he laughs. “Then we will both have gotten what we wish for: they a place in the natural world and we an opportunity in the city.”

|

Cloe Medina Erickson (medina@ericksoncreativegroup.com) holds a master’s in architecture. She is currently collaborating with locals in the Zawiya Ahansal region of Morocco on the restoration and conversion of a historic kasbah into a regional library. |

|

Free-lance photographer Kristoffer Erickson (kris@ericksoncreative group.com) has documented exploration and culture in the great mountain ranges of the world for more than a decade. He is a member of The North Face mountaineering team. The Ericksons are based in Livingston, Montana. |