|

| DINODIA PHOTOS / ALAMY |

|

Top: In Rajasthan, India, a shop sells

brightly patterned sunshade umbrellas,

which are still used in wedding and festival

processions such as this one above. |

|

| ERICH LESSING / ART RESOURCE |

|

This bronze model of an umbrella-covered

sulky-like carriage from Gansu, China dates

to the second century ce. |

n the title scene of the 1952 classic movie "Singin' in the Rain,"

Gene Kelly escorts his newfound love to her home, in the rain.

They share the shelter of his umbrella. He kisses her at her

door and then dances with his umbrella in the downpour until a

beat cop squelches his exuberance. Kelly folds the umbrella, hands

it to a passerby and walks off the scene. This sums up how most of

us today think of the umbrella: a practical item unworthy of notice

until it's raining.

n the title scene of the 1952 classic movie "Singin' in the Rain,"

Gene Kelly escorts his newfound love to her home, in the rain.

They share the shelter of his umbrella. He kisses her at her

door and then dances with his umbrella in the downpour until a

beat cop squelches his exuberance. Kelly folds the umbrella, hands

it to a passerby and walks off the scene. This sums up how most of

us today think of the umbrella: a practical item unworthy of notice

until it's raining.

It was not always so. Behind this prosaic present is a powerful

past. I first encountered a much different sort of umbrella in India.

In a market in the western province of Rajasthan, I purchased a

large, heavy bamboo umbrella whose cotton fabric was all colorful

cutwork, embroidered with animals. It could not possibly have kept out the rain.

Years later, I found out I owned a traditional wedding umbrella: At the head of a

procession of his relatives, the groom rides to his wedding on a white horse while an

attendant holds this sort of large, ornate umbrella over him. This umbrella signifies

that, at least for this one day, the groom is a king.

The royal umbrella, carried by an attendant, not only shaded the king from the sun,

but also symbolized his power in procession, battle and the hunt. For millennia, it has

been a common symbol among rulers in a huge portion of the world that includes the

Middle East, Egypt and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, Persia, South and Southeast

Asia, China, Japan and Korea. The royal umbrella flourished in Muslim, Hindu, Confucian,

Buddhist, animist and some Christian courts. Rulers sometimes bestowed umbrellas

on high officials and generals as a visible recognition of their loyalty.

|

|

|

H.E. WINLOCK, EXCAVATIONS AT DEIR EL BAHRI, 1911-1931, PLATE 13

|

CONSTANTINE AND ADELPHI ZANGAKI / LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

|

|

Just right of center, on the lower register

of this fragment of a fresco excavated

from the 14th-century bce tomb of Queen

Nefertiti, there appears a sunshade

umbrella, supported by a pair of crossed

sticks on a pole, with an additional hanging

flap. Right: This detail of an albumen print,

dated between 1860 and 1890, shows a

Cairo market in which vendors are using

sunshades of a nearly identical design. |

The royal umbrella was not an idea that spread from invention in one place—in fact

it was invented at least four times. The earliest recorded examples are from Egypt's

Fifth Dynasty, from about 2500 to 2400 bce.

Decorations on tombs and temples from

these times portray a flat, square, crossed-stick umbrella shading gods and kings. The

hieroglyph for umbrella signified sovereignty as well as the "shadow," or influence, of

a person. Thus the umbrella augmented a pharaoh's shadow. The

history of the square umbrella is long, and, although it is no longer

associated with kings, such umbrellas can still be found shading

market carts in Egypt.

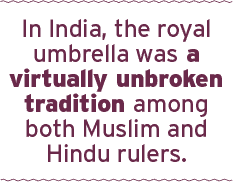

he second invention of the umbrella took place in China. A

classical text titled The Rites of Zhou from 400 bce describes

the construction and use of a round, segmented, silk umbrella

whose function was to shade ceremonial chariots. Somewhat later

reliefs illustrate such an umbrella, and archeologists have excavated

several complex brass castings used to hold the ribs of such umbrellas.

This kind of royal umbrella remained a symbol of Chinese royal privilege,

and it appears in countless court paintings. When Marco Polo

arrived at the court of Kublai Khan in 1275, he found the Mongols had

adopted many Chinese customs, including the bestowal of a special

umbrella on the highest commanders in the army:

he second invention of the umbrella took place in China. A

classical text titled The Rites of Zhou from 400 bce describes

the construction and use of a round, segmented, silk umbrella

whose function was to shade ceremonial chariots. Somewhat later

reliefs illustrate such an umbrella, and archeologists have excavated

several complex brass castings used to hold the ribs of such umbrellas.

This kind of royal umbrella remained a symbol of Chinese royal privilege,

and it appears in countless court paintings. When Marco Polo

arrived at the court of Kublai Khan in 1275, he found the Mongols had

adopted many Chinese customs, including the bestowal of a special

umbrella on the highest commanders in the army:

An officer who holds the chief command of 100,000 men, or

who is the general-in-chief of a great host, is entitled to a [gold]

tablet that weighs 300 saggi…. Every one, moreover, who holds a tablet of this

exalted degree is entitled, whenever he goes abroad, to have a little golden

canopy, such as is called an umbrella, carried on a spear over his head in token of

his high command.

From China, the royal umbrella spread to Japan and Korea. In Japan, it ceased to be

a royal prerogative within a few centuries, and it found widespread use throughout

society. Woodblock prints and paintings of the 18th century often feature a theme of

ordinary people under umbrellas in the rain. Korea, however, could not have been more

different. There the umbrella remained a strictly royal

symbol. Because Korean artwork never pictured the

emperor, his presence was signified by a horse with an

empty saddle, shaded by the royal umbrella.

|

| BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

|

On a doorway that led to the fifth-century bce

throne room in Persepolis, Iran,

a relief shows King Xerxes i shaded by an umbrella. Some two centuries

earlier, Assyrian artists showed King Ashurbanipal, below, shaded by an

umbrella with a hanging flap that resembles those depicted in Egypt. |

|

| MUSÉE DU LOUVRE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

|

| ALINARI / ART RESOURCE |

|

Ruling in Persia more than 1000 years

after Xerxes i,

Khosrau ii was depicted at

Taq-e Bostan watching a hunt from under

a royal umbrella. |

he third invention of the royal umbrella was

in Mesopotamia, centuries after the Egyptian

square parasol. In bas-reliefs at Nineveh, shading

King Ashurbanipal of Assyria, who ruled from

668 to 627 bce, is a round and pointed umbrella. From

there, the royal umbrella drifted both west and east. In

Greece, it lost its association with kingship and became

particularly associated with women. Aristophanes' play

Women at Thesmophoria satirized Athenian attitudes

toward both women and men. In the final scene, the

women boast of their steadfastness:

he third invention of the royal umbrella was

in Mesopotamia, centuries after the Egyptian

square parasol. In bas-reliefs at Nineveh, shading

King Ashurbanipal of Assyria, who ruled from

668 to 627 bce, is a round and pointed umbrella. From

there, the royal umbrella drifted both west and east. In

Greece, it lost its association with kingship and became

particularly associated with women. Aristophanes' play

Women at Thesmophoria satirized Athenian attitudes

toward both women and men. In the final scene, the

women boast of their steadfastness:

And then there's your omission

To keep up your old tradition

As the women of the race have always done:

We maintain our ancient craft

With the shuttle and the shaft

And the parasol—our shield against the sun.

These attitudes carried west to Rome, where the

umbrella was deemed too effeminate for men's use.

Juvenal, for example, wrote of a "pretty fellow, to have

presents sent to him of green sunshades." On Roman

coins, the umbrella appeared only twice, both times in

association with the Middle East: One coin was issued

around 40 ce

in Palestine and the other between 218

and 222 ce

by Emperor Heliogabalus, who was from

Syria. Overall, the Roman Empire passed on to Europe

no legacy of a royal umbrella.

East of its Mesopotamian origins, however, the royal

umbrella flourished. Bas-reliefs on the walls of Persepolis,

dating from 500 bce,

show the king seated or walking under his royal umbrella.

Later, from the third to seventh centuries, the Sassanians

ruled the next great empire that included Persia.

From their original homeland on the borders of China,

they migrated west across the Central Asian steppe, and they either brought with

them the Chinese tradition of the royal umbrella or they adopted the Persian royal

umbrella when they arrived. In either case, Sassanian kings ruled beneath royal

umbrellas, as shown on the rock-cut bas-relief at Taq-e Bostan, from about 380

ce.

In Constantinople, founded in 330 ce,

umbrellas appear prominently in Christian

artwork. With the rise of Islam in the seventh century, it becomes more difficult

to document the uses of royal umbrellas because most Islamic art favored

geometry and calligraphy over depictions of people. In Abbasid Baghdad, from the

eighth to the 13th centuries, courtiers and scholars wrote on mathematics, astronomy,

history, medicine and philosophy, but nothing about day-to-day court ritual.

It is from later texts in Egypt that we get some insight. Paula Sanders of Rice

University has analyzed three texts from Egypt that describe processions and court

ritual under the 10th- and 11th-century Fatimids, whose caliphs appeared in procession

under a royal umbrella—a practice that they attributed to the earlier Abbasid

dynasty. For the whole of the Fatimid period, factional power was constantly

shifting, and the caliph selectively bestowed the right to display an umbrella,

which signaled the recipient's support and commitment to the caliph.

|

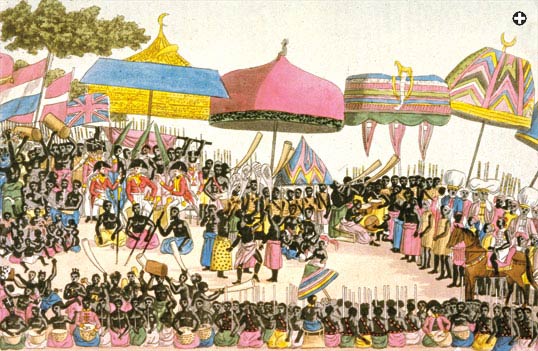

In sub-Saharan West Africa, the royal umbrella frequently appears in both

Islamic and non-Islamic kingdoms. There, it is possible that the umbrella came

south from Islamic Tunisia and Morocco, along the trade routes across the Sahara.

It is equally possible that it was indigenous—and thus yet another independent,

parallel invention. Umbrellas were part of the king's regalia in all major kingdoms

of West Africa, including Ashanti, Benin, Sokoto and Dahomey. In European

drawings from the 18th century and in early photographs

from the 19th century, kings of these states conduct royal

business from beneath a large royal umbrella.

|

| MARC CHARMET / THE ART ARCHIVE |

|

Prominently displaying large, colorful

umbrellas, this engraving dated 1820 is

titled "English Embassy in Komassi,

West Africa."

|

Rulers in East Africa, too, adopted the royal umbrella. It

is prominent in texts and frescoes in Ethiopia that date to

the 1200's, and its use continued in an unbroken tradition

well into the 20th century. Royal umbrellas were also found

in courts on the East African coast, where it is likely that

they spread via Muslim trade ties with Egypt and the lands

of the Arabian Peninsula. Ibn Battuta, the most traveled man

of the Middle Ages, reached East Africa in the 14th century.

At Mogadishu, he wrote that the king entertained him well,

feeding him delicacies from the Middle East. During processions,

Ibn Battuta noted that royal umbrellas protected the

king from the sun:

Over his head were carried four canopies of colored

silk, with the figure of a bird in gold on the top of

each canopy…. In front of him were sounded drums

and trumpets and fifes, and behind him were the

commanders of the troops, while the qadi, the doctors

of law, and the sharifs walked alongside him.

Later, both Ottoman Turkish and Safavid Persian court paintings also show royal umbrellas.

|

|

MUSEO NAZIONALE D'ARTE ORIENTALE / GIRAUDON /

BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

|

GIANNI DAGLI ORTI / THE ART ARCHIVE / ALAMY

|

|

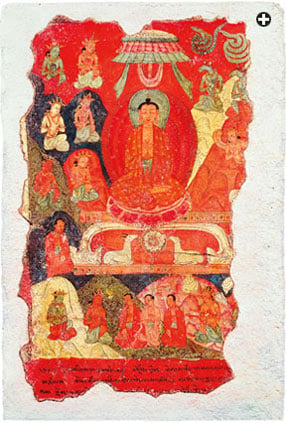

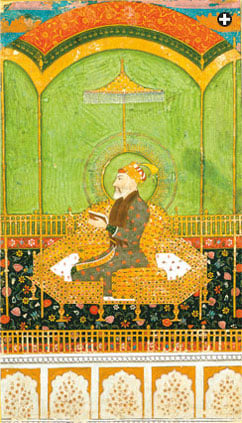

Both this Chinese-influenced Tibetan

depiction of the Buddha, left, and

this Muslim Mughal miniature of

Shah Jahan, right, date from the

17th century, and both show their

subjects seated under umbrellas. |

he fourth invention of the royal umbrella was in India, where the earliest

he fourth invention of the royal umbrella was in India, where the earliest

evidence is from Buddhist literature and reliefs dating back to about 300

bce.

In these early texts, when Siddhartha Gautama left behind his royal

upbringing to meditate on the sufferings of the world, he was shaded by a cobra's

|

| JON BOWER CAMBODIA / ALAMY |

|

Hindus, too, adopted the umbrella

in both religious and royal settings.

At Angkor, Cambodia, a statue above depicts the Hindu god Vishnu, and a

relief detail, below, depicts a battle in

which a ruler fights from beneath

an umbrella. |

hood, a tree, or an umbrella. In particular,

the umbrella became a symbol of

his successful search for enlightenment,

and in these texts he is

referred to as the "Buddha of the

White Umbrella." Early Buddhist

sculpture does not portray the Buddha,

but rather objects associated

with him: An empty platform and

the bodhi tree, a cobra or an honorific

umbrella signify his presence.

After the Buddha's death, his

followers sent small portions of his

ashes to other groups of followers,

who built mounds over the ashes.

Several umbrellas mounted on a

single shaft topped these mounds,

and these became known as stupas,

such as those built at Sanchi in

Central India around 100 bce.

The reliefs on the stupas at Sanchi

also show kings, under royal

umbrellas, arriving in

procession to honor the

Buddha. (Incidentally, multiple

umbrellas on the tops

of stupas are the origin of

the Chinese pagoda, which

added walls and made the

multiple umbrella into an

architectural form.)

|

| STEWART GORDON |

Also in the earliest Hindu writings, dating to the first four centuries of

our era, umbrellas regularly shade kings. In this quotation from the Ramayana,

Ram's father contemplates his life:

In my fathers' footsteps treading I have sought the ancient path,

Nursed my people as my children, free from passion, pride and wrath,

Underneath this white umbrella, seated on this royal throne,

I have toiled to win their welfare and my task is almost done!

|

The royal umbrella continued as an unbroken tradition for all Indian kings for the

next millennium and a half. The artwork of the southern Islamic kingdoms makes

it clear that both Muslim and Hindu kings used the royal umbrella. For example, the

Battle of Talikota, in 1386, pitted the Hindu king of Vijayanagar against the Muslim sultans

of Bijapur, Golconda, Bidar and Ahmadnagar. A contemporary painting shows the

adversaries approaching the battle under their respective royal umbrellas. Throughout

the British colonial period, India's princes ruled from beneath royal umbrellas—some

of which were by then manufactured in London. When he visited India in 1911, King

George of England walked beneath a royal umbrella.

ometime around 800 ce,

the royal umbrella began to flourish in Southeast Asia,

adopted by kings in Cambodia, Laos, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam and Java. The

custom may have come from India or China, as both cultures strongly influenced

the region at the time. A charming story from 12th-century Burma illustrates the

umbrella's symbolic power: The king was unable to choose his successor from among

his five sons. One night, he ordered his royal umbrella set up, and he commanded that

his sons sleep in a circle around it. The successor was chosen when the umbrella fell

in one son's direction, and in the chronicles he became known as "the king whom the

umbrella placed on the throne."

ometime around 800 ce,

the royal umbrella began to flourish in Southeast Asia,

adopted by kings in Cambodia, Laos, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam and Java. The

custom may have come from India or China, as both cultures strongly influenced

the region at the time. A charming story from 12th-century Burma illustrates the

umbrella's symbolic power: The king was unable to choose his successor from among

his five sons. One night, he ordered his royal umbrella set up, and he commanded that

his sons sleep in a circle around it. The successor was chosen when the umbrella fell

in one son's direction, and in the chronicles he became known as "the king whom the

umbrella placed on the throne."

|

|

GAHOE MUSEUM / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

|

MELVYN LONGHURST / ALAMY

|

|

From Korea, a religious painting uses an umbrella,

left, as does a modern statue of King Naresuan

in Thailand, right. |

|

|

|

MUSÉE GUIMET / GIANNI DAGLI ORTI / THE ART ARCHIVE / ALAMY

|

THE PRINT COLLECTOR / ALAMY

|

|

Left: Arriving in Japan in the 17th

century, the Portuguese ambassador was

depicted under an elaborate umbrella.

Right: Japan was one of the few places

where umbrellas became objects of fashion

from an early time, and today the bamboo

parasol remains a national folkloric symbol. |

Two of the most famous early sites in Southeast

Asia, Borobudur in Central Java, which dates from

the eighth and ninth centuries, and Angkor in Cambodia,

dating from the 10th to 12th centuries, are

both replete with umbrellas. Among the nearly 3000

reliefs adorning Borobudur, umbrellas identify kings,

nobility and famous figures from the Buddha's life.

At Angkor, a huge bas-relief portrays a battle

between the Cambodians and the Champa kingdom

(in current-day Vietnam). On it, generals and noble

advisors all have umbrellas, supporting speculation

that, as in Fatimid Egypt, bestowal of an umbrella

cemented loyalty. The king, however, has more

umbrellas surrounding him than anyone else—15 in

all—complete with an entourage of umbrella carriers.

In Burma as in India, the tradition continued

into the 19th century. Dutch and British emissaries

observed the king shaded by umbrellas in processions,

and they negotiated with the king while he was seated

under his royal umbrella. In 1867, the English resident

at the Burmese court and his wife were granted the

privilege of an umbrella, likely a political move aimed

at holding off a British takeover. (It was not enough,

however, and the British did take over Burma in 1885.)

Thailand, which remained more or less independent,

continued its tradition of the royal umbrella until

recent decades, and in 1967, Jacqueline Kennedy, wife

of us

president John F. Kennedy, was granted a ceremonial

umbrella when she visited Thailand.

|

| PHOTOSERVICE ELECTA MONDADORI / ART RESOURCE |

|

Although Europe never fully embraced the royal

umbrella, the late-18th-century artist Laurent Pechaux

painted one over Pope Gregory xi, above;

the 17th-'century French artist Charles Le Brun painted two

above a chancellor, below left, and an 1894 fashion print

from France shows a lady's parasol tensioned by

springy ribs of newly available lightweight steel. |

|

|

| ERICH LESSING / ART RESOURCE |

PHOTOS12 / ALAMY |

he earliest evidence of an umbrella in Europe

comes from the Utrecht Psalter, which is generally dated to the 900's. One of its

illustrations shows an angel holding an umbrella over King David. However, it is

not until the 13th century that scholars have found evidence of a royal umbrella, and then

only in Italy, which at that time was receiving much culture and learning from Islamic

Spain, including medicine, philosophy, cuisine, music and the game of chess. Venice, with

its close trading ties to the Islamic world, adopted the umbrella for the doge when he was

in a procession, and so did the pope in Rome. But the royal umbrella just never caught on

in Europe. In addition to its cooler climate, the influence

of the Crusades led courts by 1300 to regard the royal

umbrella as a foreign symbol, one used by enemies. By the

end of the 18th century, even the papal umbrella had been

replaced by a four-cornered, flat canopy.

he earliest evidence of an umbrella in Europe

comes from the Utrecht Psalter, which is generally dated to the 900's. One of its

illustrations shows an angel holding an umbrella over King David. However, it is

not until the 13th century that scholars have found evidence of a royal umbrella, and then

only in Italy, which at that time was receiving much culture and learning from Islamic

Spain, including medicine, philosophy, cuisine, music and the game of chess. Venice, with

its close trading ties to the Islamic world, adopted the umbrella for the doge when he was

in a procession, and so did the pope in Rome. But the royal umbrella just never caught on

in Europe. In addition to its cooler climate, the influence

of the Crusades led courts by 1300 to regard the royal

umbrella as a foreign symbol, one used by enemies. By the

end of the 18th century, even the papal umbrella had been

replaced by a four-cornered, flat canopy.

|

Later, there were exceptions. Portuguese and Spanish colonial traders returned

from Asia with umbrellas, and around the 16th century those lost their royal status

and became occasional items of courtly fashion. Though Mary Queen of Scots owned

one in 1562, and the term "ombrello" appeared in an Italian–English dictionary

of 1598, they were unknown in the larger society. It was only in the 18th century that

umbrellas caught on as a fashion item—and that still as sunshades made of cotton

or thin leather, of no use in the rain. In the 19th century, these ladies' parasols went

through almost yearly fashion shifts.

|

| ASIA IMAGES GROUP / ALAMY |

|

In modern times, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah of Brunei, above,

used a yellow umbrella at a ceremony on his birthday, and a traditional ruler

in Ghana, below, used several in his party for a corn festival parade

in Accra. The large umbrellas in the background resemble the ones

depicted in the early 19th century. |

|

| OLIVER ASSELIN / ALAMY |

The water-resistant umbrella first appeared in England in the late 18th

century to protect clerics and officials during outdoor duties. They were heavy,

stiff and slow to dry. They leaked, their whalebone ribs rotted quickly, and the folding

mechanisms often failed. All umbrellas, whether to protect from rain or sun,

were deemed too "feminine" for ordinary Englishmen.

With the Industrial Revolution

came lightweight steel and, with that, a drive to make a light, foldable,

rainproof umbrella. Inventors in Europe and America filed hundreds of patents

for folding mechanisms, rib arrangements and even provisions for concealing

swords or pistols in umbrellas. Following dozens of minor improvements, the

modern umbrella began to emerge, and by 1910, Britain was exporting more than three

million a year—many to Asia. Germany and Italy were Britian's chief competitors, making

cheaper models.

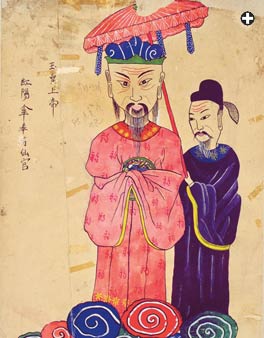

his long and complicated history of the umbrella shows that it did not simply

"diffuse" from one place of invention outward to a wider world. It was invented at

least four times, and it moved in unpredictable ways, sometimes never leaving its

country of origin, like the Egyptian square umbrella, and other times moving into a society

that completely changed its meanings and uses. Greece, Rome and 18th-century England

deemed the umbrella "feminine," while the Japanese umbrella was acceptable for both

men and women but spread from royal to general use.

his long and complicated history of the umbrella shows that it did not simply

"diffuse" from one place of invention outward to a wider world. It was invented at

least four times, and it moved in unpredictable ways, sometimes never leaving its

country of origin, like the Egyptian square umbrella, and other times moving into a society

that completely changed its meanings and uses. Greece, Rome and 18th-century England

deemed the umbrella "feminine," while the Japanese umbrella was acceptable for both

men and women but spread from royal to general use.

|

|

MUSEE DE LA VILLE DE PARIS /

MUSEE CARNAVALET / GIRAUDON /

BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

THE ART ARCHIVE |

|

The unreliability of Europe's early steel

umbrellas caught the eye of French satirist

Daumier, left, but by the time Gene

Kelly turned his bumbershoot into an iconic

Hollywood dance prop in "Singin' in the

Rain," right, the waterproof umbrella had become

plain and practical, offering little hint of its

symbolic and powerful past. |

Several points about this complicated

process seem significant. Rulers everywhere

seek symbols that enhance dignity,

visibility and the loyalty of subjects. They

were willing to experiment with new

symbols, such as the royal umbrella. Several

sorts of travelers, such as emissaries, traders,

monks, learned men and professional

soldiers, brought back, often over long distances,

information about royal symbols. For

centuries, the royal umbrella was part of a

shared courtly world that stretched from

Asia to Africa and Spain. It was part of a

familiar courtly scene to those who traveled

for political reasons, business or advancement.

The royal umbrella was frequently a

potent political symbol. Because it was tied to

no religion, region, language or ethnic group,

kings could use it to rally disparate groups.

The umbrella was also, however, granted

to a select few at court. When the recipient

traveled under it, every observer knew of his

personal ties to the king. It was a public commitment of personal loyalty, important in times

of factional strife and threats to the throne—a situation all too frequent among kings.

Today, the world of the royal umbrella is almost entirely gone, but with imagination

and the memory of history, we can recall the lavish decorations, dignified processions and

royal associations it carried—every time it rains and we pop open our umbrella.

|

Stewart Gordon is a senior research scholar at the Center for South Asian Studies, University of Michigan. His recent books include When Asia was the World (Da Capo, 2008) and Routes: How the Pathways of Goods and Ideas Shaped Our World (University of California Press, forthcoming 2012). |