acing the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

stands the Jefferson Building, the main building of the Library of Congress, the world's largest library,

with holdings of more than

140 million books and other printed items. The stately building, with its neoclassical exterior,

copper-plated dome and marble halls, is named after Thomas Jefferson, one of the "founding

fathers" of the United States, principal author of the 1776 Declaration of Independence and,

from 1801 to 1809, the third president of

the young republic. But the name also

recognizes Jefferson's role as a founder

of the Library itself. As president, he

enshrined the institution in law and, in

1814, after a fire set by British troops during

the Anglo-American War destroyed

the Library's 3000-volume collection, he

offered all or part of his own wide-ranging

book collection as a replacement for the

losses, commenting that "there is in fact no

subject to which a member of Congress

may not have occasion to refer."

acing the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

stands the Jefferson Building, the main building of the Library of Congress, the world's largest library,

with holdings of more than

140 million books and other printed items. The stately building, with its neoclassical exterior,

copper-plated dome and marble halls, is named after Thomas Jefferson, one of the "founding

fathers" of the United States, principal author of the 1776 Declaration of Independence and,

from 1801 to 1809, the third president of

the young republic. But the name also

recognizes Jefferson's role as a founder

of the Library itself. As president, he

enshrined the institution in law and, in

1814, after a fire set by British troops during

the Anglo-American War destroyed

the Library's 3000-volume collection, he

offered all or part of his own wide-ranging

book collection as a replacement for the

losses, commenting that "there is in fact no

subject to which a member of Congress

may not have occasion to refer."

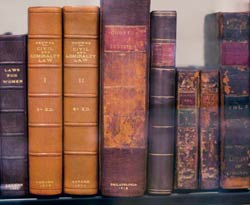

Among the nearly 6500 books Jefferson

sold to the Library was a two-volume

English translation of the Qur'an, the book

Muslims recite, study and revere as the

revealed word of God. The presence

of this Qur'an, first in Jefferson's private

library and later in the Library of Congress,

prompts the questions why Jefferson

purchased this book, what use he made

of it, and why he included it in his young

nation's repository of knowledge.

These questions are all the more pertinent

in light of assertions by some present-

day commentators that Jefferson

purchased his Qur'an in the 1780's in

response to conflict between the us and the

"Barbary states" of North Africa—today

Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. That

was a conflict Jefferson followed closely—

indeed, in 1786, he helped negotiate a treaty

with Morocco, the United States' first treaty

with a foreign power. Then, it was relations

with Algeria that were the most nettlesome,

as its ruler demanded the payment of tribute

in return for ending semiofficial piracy

of American merchant shipping. Jefferson

staunchly opposed tribute payment. In

this context, such popular accounts claim,

Jefferson was studying the Qur'an to better

understand these adversaries, in keeping

with the adage "know thy enemy." However,

when we look more closely at the place of

this copy of the Qur'an in Jefferson's

library—and in his thinking—

and when we examine

the context of this

particular translation,

we see a different story.

rom his youth,

Thomas Jefferson

read and collected

a great number of

books, and a wide variety

of them: The collection

he eventually sold to

the Library of Congress

comprised 6487 volumes,

ranging in subject from

classical philosophy to cooking. Like many

collectors of the time, Jefferson not only cataloged

his books but also marked them. It is

his singular way of marking his books that

makes it possible to establish that, among

the millions of volumes in today's Library of

Congress, this one specific Qur'an did indeed

belong to him.

rom his youth,

Thomas Jefferson

read and collected

a great number of

books, and a wide variety

of them: The collection

he eventually sold to

the Library of Congress

comprised 6487 volumes,

ranging in subject from

classical philosophy to cooking. Like many

collectors of the time, Jefferson not only cataloged

his books but also marked them. It is

his singular way of marking his books that

makes it possible to establish that, among

the millions of volumes in today's Library of

Congress, this one specific Qur'an did indeed

belong to him.

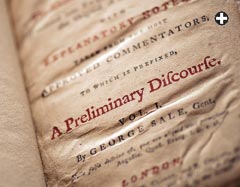

|

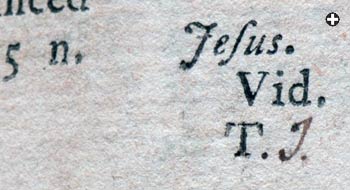

| The initials "T.J." were Thomas Jefferson's

device for marking his books: On this

page, the "T." is the printer's mark to help

the binder keep each 16-page "gathering"

in sequence, and the "J." was added

personally by Jefferson. |

In the 18th century, the production of

books was still an essentially manual process.

By means of a hand press, large sheets

of paper were printed on both sides with

multiple pages before being folded. They

were folded once to produce four pages for

the folio size, twice to produce eight pages

for the quarto or four times to produce the

16-page octavo. These folded sheets, known

as "gatherings," were then sewn together

along their inner edges before being attached

to the binding. To ensure that the bookbinders

would stitch the gatherings together in

the correct sequence, each was marked with

a different letter of the alphabet on what,

after folding, would become that gathering's

first page.

Thus, in an octavo volume like Jefferson's

Qur'an, there is a small printed letter in

the bottom right-hand corner of every 16th

page. It was Jefferson's habit to take advantage

of these preexisting marks to discreetly

inscribe each of his books. On each book's

10th gathering, in front of the printer's mark

J he wrote a letter T, and on the 20th gathering,

to the printed T he added a J, thereby in

each case producing his initials. This subtle

yet unmistakable signature appears clearly

on the two leather-bound volumes in the

Library of Congress.

|

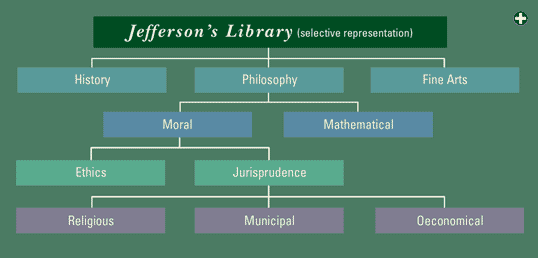

Jefferson's system of cataloging his library

sheds light on the place the Qur'an held in

his thinking. Jefferson's 44-category classification

scheme was much informed by the

work of Francis Bacon (1561–1626), whose

professional trajectory from lawyer to statesman

to philosopher roughly prefigures Jefferson's

own career. According to Bacon,

the human mind comprises three faculties:

memory, reason and imagination. This

trinity is reflected in

Jefferson's library, which

he organized into history,

philosophy and fine

arts. Each of these contained

subcategories:

philosophy, for instance,

was divided into moral

and mathematical; continuing

along the former

branch leads to

the subdivision of ethics

and jurisprudence,

which itself was further

segmented into the

categories of religious,

municipal and "oeconomical."

Jefferson's system for organizing his

library has often been described as a "blueprint

of his own mind." Jefferson kept his

Qur'an in the section on religion, located

between a book on the myths and gods of

antiquity and a copy of the Old Testament.

It is illuminating to note that Jefferson

did not class religious works with books

on history or ethics—as might perhaps be

expected—but that he regarded their proper

place to be within jurisprudence.

|

| Jefferson organized his

own library, and he

shelved religious books,

including his English

version of the Qur'an,

with other works under

"Jurisprudence," which

fell under "Moral

Philosophy." |

The story of Jefferson's purchase of the

Qur'an helps to explain this classification.

Sifting through the records of the Virginia

Gazette, through which Jefferson ordered

many of his books, the scholar Frank Dewey

discovered that Jefferson bought this copy of

the Qur'an around 1765, when he was still a

student of law at the College of William &

Mary in Virginia. This quickly refutes the

notion that Jefferson's interest in Islam came

in response to the Barbary threat to shipping.

Instead, it situates his interest in the Qur'an

in the context of his legal studies—a conclusion

that is consistent with his shelving of it

in the section on jurisprudence.

Jefferson's legal interest in the Qur'an was

not without precedent. There is of course

the entire Islamic juridical tradition of religious

law (Shari'ah) based on Qur'anic exegesis,

but Jefferson had an example at hand that

was closer to his own tradition: The standard

work on comparative law during his time was

Of the Law of Nature and Nations, written by

the German scholar Samuel von Pufendorf

and first published in 1672. As Dewey shows,

Jefferson studied Pufendorf's treatise intensively

and, in his own legal writings, cited it

more frequently than any other text. Pufendorf's

book contains numerous references

to Islam and to the Qur'an. Although many

of these were disparaging—typical for European

works of the period—on other occasions

Pufendorf cited Qur'anic legal precedents

approvingly, including the Qur'an's emphasis

on promoting moral behavior, its proscription

of games of chance and its admonition

to make peace between warring countries.

As Kevin Hayes, another eminent Jefferson

scholar, writes: "Wanting to broaden his legal

studies as much as possible,

Jefferson found the

Qur'an well worth his

attention."

In his reading of the

Qur'an as a law book,

Jefferson was aided by a

relatively new English

translation that was not

only technically superior

to earlier attempts, but also produced with a

sensitivity that was not unlike Jefferson's own

emerging attitudes. Entitled The Koran; commonly

called the Alcoran of Mohammed, it was

prepared by the Englishman George Sale and

published in 1734 in

London. A second

edition was printed

in 1764, and it was

this edition that Jefferson

bought. Like

Jefferson, Sale was a

lawyer, although his

heart lay in oriental

scholarship. In the

preface to his translation,

he lamented

that the work "was

carried on at leisure

time only, and

amidst the necessary

avocations of a troublesome

profession."

This preface also

informed the reader

of Sale's motives:

"If the religious and

civil Institutions of

foreign nations are

worth our knowledge,

those of

Mohammed, the

lawgiver of the Arabians,

and founder of

an empire which in

less than a century spread itself over a greater

part of the world than the Romans were ever

masters of, must needs be so." Like Pufendorf,

Sale stressed Muhammad's role as a "lawgiver"

and the Qur'an as an example of a distinct

legal tradition.

This is not to say that Sale's translation is

free of the kind of prejudices against Muslims

that characterize most European works on

Islam of this period. However, Sale did not

stoop to the kinds of affronts that tend to fill

the pages of earlier such attempts at translation.

To the contrary, Sale felt himself obliged

to treat "with common decency, and even to

approve such particulars as seemed to me to

deserve approbation." In keeping with this

commitment, Sale described the Prophet

of Islam as "richly furnished with personal

endowments, beautiful in person, of a subtle

wit, agreeable behaviour, shewing liberality

to the poor, courtesy to every one, fortitude

against his enemies, and, above all, a high

reverence for the name of God." This portrayal

is markedly different from those of earlier

translators, whose primary motive was to

assert the superiority of Christianity.

In addition to the relative liberality of

Sale's approach, he also surpassed earlier

writers in the quality of his translation. Previous

English versions of the Qur'an were not

based on the original Arabic, but rather on

Latin or French versions, a process that layered

fresh mistakes upon the errors of

their sources. Sale, by contrast, worked

from the Arabic text. It was not true,

as Voltaire claimed in his famous Dictionnaire

philosophique of 1764, that le savant Sale had acquired his

Arabic skills by having lived for 25 years among Arabs; rather, Sale

had learnt the language through his involvement in preparing

an Arabic translation of the New Testament to

be used by Syrian Christians, a project

that was underwritten by the Society for the Promotion

of Christian Knowledge in London. Studying

alongside Arab scholars who had come

to London to assist in this work, he acquired

within a few years such good command of the

language that he was able to serve as a proofreader

of the Arabic text.

It is thus not so surprising that Sale

turned from translating the holy text of

Christians into Arabic to rendering the holy text of Muslims into his

native English. Noting the

absence of a reliable English

translation, he aimed

to provide a "more genuine

idea of the original."

Lest his readers be unduly

daunted, he justified his

choice of fidelity to the

original by stating that "we

must not expect to read a

version of so extraordinary

a book with the same ease

and pleasure as a modern

composition." Indeed, even

though Sale's English may

appear overwrought today,

there is no denying that he

strove to convey some of

the beauty and poetry of

the original Arabic.

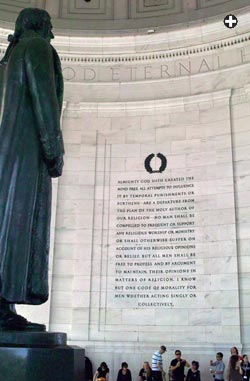

|

|

An inscription inside the

Jefferson Memorial in

Washington, D.C. quotes

Jefferson's 1777 statute on

religious pluralism that

inspired the constitutional

right that "no religious

Test shall ever be required

as a Qualification to any

Office or public Trust." |

Sale's aspiration to provide

an accurate rendition

of the Qur'an was

matched by his desire also

to provide his readers with

a more honest introduction

to Islam. This "Preliminary

Discourse," as he

entitled it, runs to more

than 200 pages in the

edition Jefferson purchased.

Fairly presented

and conscientiously documented,

it contains a section

on Islamic civil law

that repeatedly points out

parallels to Jewish legal

precepts in regard to marriage,

divorce, inheritance,

lawful retaliation

and the rules of warfare.

In this substantial discussion,

Sale displays the

same quality of dispassionate

interest in comparative

law that later

moved Jefferson.

ut did reading the

Qur'an influence

Thomas Jefferson?

That question is difficult

to answer, because

the few scattered references

he made to it in his

writings do not reveal

his views. Though it may

have sparked in him a

desire to learn the Arabic

language (during

the 1770's Jefferson purchased

a number of Arabic

grammars), it is far

more significant that it

may have reinforced his

commitment to religious

freedom. Two examples

support this idea.

ut did reading the

Qur'an influence

Thomas Jefferson?

That question is difficult

to answer, because

the few scattered references

he made to it in his

writings do not reveal

his views. Though it may

have sparked in him a

desire to learn the Arabic

language (during

the 1770's Jefferson purchased

a number of Arabic

grammars), it is far

more significant that it

may have reinforced his

commitment to religious

freedom. Two examples

support this idea.

In 1777, the year

after he drafted the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was

tasked with excising colonial legacies from

Virginia's legal code. As part of this undertaking,

he drafted a bill for the establishment

of religious freedom, which was

enacted in 1786. In his autobiography, Jefferson

recounted his strong desire that the

bill not only should extend to Christians of

all denominations but should also include

"within the mantle of its protection, the Jew

and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan

[Muslim], the Hindoo, and infidel of

every denomination."

This all-encompassing attitude to religious

pluralism was by no means universally

shared by Jefferson's contemporaries.

As the historian Robert Allison documents,

many American writers and statesmen

in the late 18th century made reference to

Islam for less salutary aims. Armed with

tendentious translations and often grossly

distorted accounts, they portrayed Islam as

embodying the very dangers of tyranny and

despotism that the young republic had just

overcome. Allison argues that many American

politicians who used "the Muslim world

as a reference point for their own society

were not concerned with historical truth

or with an accurate description of Islam,

but rather with this description's political

convenience."

|

|

|

These attitudes again came into conflict

with Jefferson's vision in 1788, when the states voted to ratify the United States Constitution.

One of the matters at issue was the

provision—now Article vi, Section 3—that

"no religious Test shall ever be required as

a Qualification to any Office or public Trust

under the United States." Some Anti-Federalists

singled out and opposed this ban on

religious discrimination by painting a hypothetical

scenario in which a Muslim could

become president. On the other side of the

argument, despite their frequent opposition

to Jefferson on other matters, the Federalists

praised and drew on Jefferson's vision of

religious tolerance in supporting uncircumscribed

rights both to faith and to elected

office for all citizens. As the historian Denise

Spellberg shows in her examination of this

dispute among delegates in North Carolina,

in the course of these constitutional debates "Muslims became symbolically

embroiled in the definition of what it meant to be American citizens."

It is intriguing to think that Jefferson's study of the

Qur'an may have inoculated him—to a degree that

today we can only surmise— ainst such popular prejudices

about Islam, and it may have informed his conviction

that Muslims, no less and no more than any other

religious group, were entitled to all the legal rights

his new nation could offer. And although Jefferson was

an early and vocal proponent of going to war

against the Barbary states over their attacks

on us shipping, he never framed his arguments

for doing so in religious terms, sticking

firmly to a position of political principle. Far

from reading the Qur'an to better understand

the mindset of his adversaries, it is likely that

his earlier knowledge of it confirmed his

analysis that the roots of the Barbary conflict

were economic, not religious.

Sale's Koran remained the best available

English version of the Qur'an for another 150

years. Today, along with the original copy of

Jefferson's Qur'an, the Library of Congress

holds nearly one million printed items relating

to Islam—a vast collection of knowledge

for every new generation of lawmakers and

citizens, with its roots in the law student's

leather-bound volumes.

|

Sebastian R. Prange

(s.prange@gmail.com) holds a doctorate in history from

the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. He studies the

organization of Muslim trade networks in the pre-modern Indian Ocean, with a regional

focus on South India. |

|

Aasil Ahmad

(www.aasilahmad.net) is a freelance photographer and photo

editor for Islamic Monthly magazine. He recently completed a project in Kashmir teaching

photography to children impacted by the 2005 earthquake. His photos of the Hajj were

featured in a series called "A Minox in Mecca" at the Contact Photography Festival in

Toronto. He lives in Washington, D.C.

|