|

|

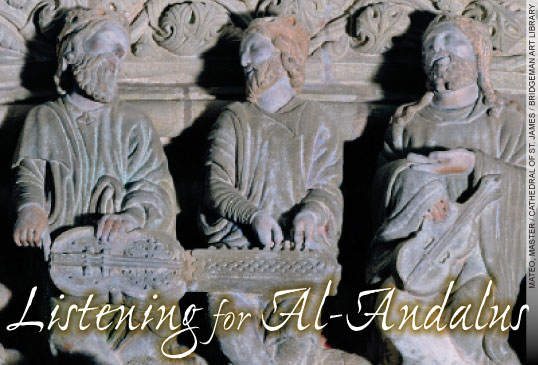

Their Iberian predecessors include these

frieze figures from Santiago de

Compostele, Spain.

|

|

ne of the world's most influential

musical cultures flourished from the

eighth to the 15th century in the southern

Iberian realm called al-Andalus by the

Arabs who lived and ruled there. Only

traces of that original music remain today,

in poems, written histories, illustrations

and oral traditions handed down through

generations, yet Andalusian music and its

many descendants still inspire performers

and audiences around the world.

ne of the world's most influential

musical cultures flourished from the

eighth to the 15th century in the southern

Iberian realm called al-Andalus by the

Arabs who lived and ruled there. Only

traces of that original music remain today,

in poems, written histories, illustrations

and oral traditions handed down through

generations, yet Andalusian music and its

many descendants still inspire performers

and audiences around the world.

Arabs have always considered the

music of al-Andalus a pinnacle of Arab

culture. It gave rise to poetry and song

forms that influenced the European

troubadours, whose music in turn became

part of the Renaissance, and is still

heard today.

Often attracted first by the romantic

reputation of al-Andalus, modern-day

musicians worldwide love to "reimagine"

its music, blending beautiful old Spanish

melodies with Middle Eastern, medieval,

flamenco and gypsy influences. Many

performers and audiences are also

inspired by the ideal of convivencia, the

complex co-existence that occurred

among Islamic, Jewish and Christian

cultures in al-Andalus.

Anthropologist Jonathan Shannon of

New York's Hunter College writes about

the music and culture of al-Andalus.

"Today, people look at our world full of

conflict, and romantically view the period

of al-Andalus as one of cultural tolerance

where Muslims, Jews and Christians all

got along and created wonderful poetry,

music, food and architecture. They think

that if we want to understand tolerance

today, let's look back to medieval Spain.

Some people see that as a potential loose

model for how the world should be."

Those people, he says, and many modern

Arabs as well, often see al-Andalus as

a "golden age." In Spain itself, after

centuries of willful forgetting of the

contributions of Muslims and Jews to

the national history, Spanish musicians

and artists have for some decades reveled

in a kind of willful remembering—and

re-mythologizing—of their multicultural

past.

|

|

Echoing the Middle Ages from his Madrid

studio, Eduardo Paniagua plays a psaltery,

or lap harp, as longtime collaborator Wafir

Sheikh el-Din plays an 'ud, or fretless lute.

Their Iberian predecessors include the illustration,

below, that Paniagua chose for the cover

of one of his most popular recordings,

"The Best of the Cantigas."

|

|

For Madrid musician, architect and recording producer

Eduardo Paniagua, reimagining the elusive music of

al-Andalus is a lifelong passion that has led him

on a musical journey across continents, centuries

and cultures. Blending a kind of musical

archeology with his own imagination,

Paniagua has spent decades teasing out

musical threads from the past and weaving

them into something new and alive.

He plays on both medieval Spanish and

modern Middle Eastern instruments. He

hunts for songs and poems in old manuscripts,

finds inspiration in poems on

palace walls and studies images of musical

instruments in drawings and carved

reliefs. He seeks out living masters of

Arab music in North Africa and rescues

historic recordings from oblivion.

"It's a joy to be able to do this work,"

Paniagua reflects. "Yet I don't know why it

entered me. I don't know why I have this

love of Arab music and early music. I only

know that I love it."

|

usic was an integral part of daily

life in al-Andalus, from the first

days the Arabs arrived in 711 until years

after the last Arab ruler was expelled from

Granada in 1492. Holidays and weddings

were incomplete without music and dancing.

Professional singers, male and female,

were attached to aristocratic homes and

royal courts. Al-Andalus's most famous

musician was Ziryab, originally from

Baghdad. After arriving in Córdoba in

822, he established a music school and

set down rules for classical music

performances. These suites of vocal and

instrumental music are known now as

the nubah. He is best known for innovating

the tuning and playing of the 'ud, the

unfretted lute, Arab music's signature

string instrument and predecessor of

the modern guitar. Especially in Seville,

craftsmen refined and invented musical

instruments. Polymath thinkers wrote

about music theory. Andalusian musicians

developed their own interpretations of the

maqamat, or modes and scales, that grew

distinct from those of the eastern Arab

world. Around the year 1000, when the

original Andalusian caliphate splintered

into smaller states, two new forms of

popular poetry sprang up and were set to

music: muwashshah and zajal.

usic was an integral part of daily

life in al-Andalus, from the first

days the Arabs arrived in 711 until years

after the last Arab ruler was expelled from

Granada in 1492. Holidays and weddings

were incomplete without music and dancing.

Professional singers, male and female,

were attached to aristocratic homes and

royal courts. Al-Andalus's most famous

musician was Ziryab, originally from

Baghdad. After arriving in Córdoba in

822, he established a music school and

set down rules for classical music

performances. These suites of vocal and

instrumental music are known now as

the nubah. He is best known for innovating

the tuning and playing of the 'ud, the

unfretted lute, Arab music's signature

string instrument and predecessor of

the modern guitar. Especially in Seville,

craftsmen refined and invented musical

instruments. Polymath thinkers wrote

about music theory. Andalusian musicians

developed their own interpretations of the

maqamat, or modes and scales, that grew

distinct from those of the eastern Arab

world. Around the year 1000, when the

original Andalusian caliphate splintered

into smaller states, two new forms of

popular poetry sprang up and were set to

music: muwashshah and zajal.

As the centuries passed, the musical

and poetic ideas of al-Andalus spread

north into Europe, south into North

Africa and east into Egypt and beyond.

Later, after 1492, additional waves of

exiles from the Muslim and Jewish communities

of al-Andalus moved to North

Africa and points east, bringing with

them music and poetry, while those Arabs

and Jews who remained in Spain kept

making their own style of music until

speaking and singing in Arabic were officially

banned in the 16th century.

Though most books on Andalusian

music theory were lost, anecdotes about

that musical world point to its exuberance.

Some old muwashshahat poems survived,

and they are still sung in Egypt, Lebanon

and Syria. The classical nubah vocal and

instrumental suite tradition incorporated

many muwashshahat, and the poems

live on in the nubah tradition, mainly in

Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Tunisia.

The trouble for musicians today is

that they can't be certain that the repertoires

performed by modern ensembles in

North Africa and the eastern Arab world

in fact use the same melodies once played

in al-Andalus, or even close approximations.

There are simply no written musical

scores of music from Andalusian

times. Musicians in medieval Europe

and the Middle East didn't help the situation

either, since they regularly set old

poems to new melodies, and

new poems to old melodies.

Thus a muwashshah heard

in Egypt today might be set to

an old Andalusian poem, but

the melody may be only 100

years old.

Folklore and music historian

Dwight Reynolds has

been studying the music of

al-Andalus and North Africa

for two decades. "It is quite

probable that a large part of

the Andalusi music repertoire

is old. We just can't tell which

part," he says.

This allows—or forces—modern musicians who

attempt to revive the sounds

of al-Andalus to make many

bold choices and judgments

that inevitably open them

up to criticism. First, they

must select repertoire from

the living, mostly North African, traditions

or from written traces of "lost"

music. Then they must decide whether

to perform in a large ensemble (such

as the modern groups in North Africa)

or in a smaller group (such as a typical

eastern Arab ensemble), or to follow

historic Arabic sources that usually

describe a solo singer accompanied by a

single instrument. Musicians also have

to decide whether they'll play modern or

antique instruments, and then they must

also choose rhythmic and vocal stylistic

interpretation.

or Paniagua, such uncertainty has

become familiar territory, and one

key to his enduring passion, he says, is

that it started early, at home. Born in 1952

in Madrid to an unusually musical family,

Paniagua was the son of a well-known

hematologist who collected records and

filled the house with music played on the

family record player.

or Paniagua, such uncertainty has

become familiar territory, and one

key to his enduring passion, he says, is

that it started early, at home. Born in 1952

in Madrid to an unusually musical family,

Paniagua was the son of a well-known

hematologist who collected records and

filled the house with music played on the

family record player.

"We loved all kinds of music, not only

classical," Paniagua says, smiling. "And in

our house there

was no television.

Only music."

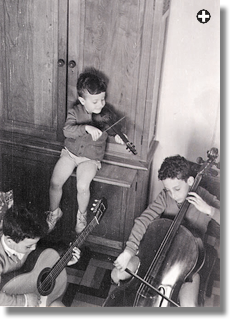

Eduardo is the third of four brothers:

Gregorio and Carlos are older

and Luis younger. Gregorio studied cello

at the Madrid conservatory, and as boys

the three younger Paniagua brothers also

picked up instruments. In the early 1960's,

Gregorio became fascinated with the

early-music movement in Europe and

the us.

In 1964, when Eduardo was 12,

Gregorio formed a band called Atrium

Musicae ("The Music Court") that included

his brothers. They began to perform

medieval music on period instruments,

using historic drawings and paintings as a

guide. The group first performed in local

high schools, and gradually expanded to

museums and theaters.

"It was a golden age in the family," recalls Luis.

The Paniagua brothers made their first

recordings in 1969. Eventually they made

22 records, including an album of classical

Greek music based on notations on papyrus

fragments. The group toured Europe

and the us,

and in 1972 it performed at

New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

|

Together Paniagua and Sheikh el-Din have toured and collaborated with dozens

of musicians and groups since the 1990's. |

|

Medieval artworks are characteristic elements

on the covers of Pneuma's more than 120 recordings.

Such art tells us much about and how music was performed.

|

|

Luis Delgado is another prominent

Spanish musician who finds inspiration

for his many compositions and recordings

in the musical heritage of al-Andalus. As

a young man, he performed and recorded

with Atrium Musicae. "I have a very positive

feeling from that time," he recalls.

Gregorio, he says, "opened our minds to

early music with a concept of freedom

and joy."

During the heyday of Atrium

Musicae, Eduardo and his brothers first

encountered the classical music of North

Africa. Eduardo recalls that Gregorio

heard some recordings and, while on his

honeymoon in Morocco, sought

out masters of the traditional

music known as ala, the local

term for the nubah. Gregorio

later brought the highly regarded

classical Tetouan ensemble of Abd

al-Sadiq Shiqara to Spain to record

courtly music from the 12th and 13th centuries.

The connections that the Spanish members of

Atrium Musicae made with their Moroccan counterparts

launched them into a far more profound series

of encounters with the music of al-Andalus and

North Africa. Just three years later, Atrium Musicae

recorded instrumental selections from the North African

repertoire played on medieval Spanish instruments.

After Atrium Musicae disbanded in

1984, Eduardo, Carlos and Luis Paniagua

formed Calamus, a group that also

included Luis Delgado and Begonia Olavide,

whose specialty was the psaltery,

or medieval lap harp. Calamus produced

two cds

using medieval Spanish and Arab

instruments, which reflected their growing

knowledge of the traditions.

|

|

COURTESY EDUARDO PANIAGUA |

| Growing up in Madrid with

brothers Luis (center), Carlos

(right) and Gregorio (not shown),

Eduardo (left) recalls, "We loved

all kinds of music, not only

classical. And in our house there

was no television. Only music." |

Reynolds has followed these musicians

over the decades. "If their first efforts now

seem uninformed, much to their

credit they all took it very seriously,

and for a couple of decades

now have pushed further and

further into the tradition. They

could have stopped with the type

of music they were doing in the

1970's, but they didn't. They kept

on studying, and they kept on

collaborating."

Carlos married Olavide, and

the couple now lives in Tangier,

where he works as a luthier of

early string instruments, working

from medieval illustrations and

other artwork. He and Olavide

regularly perform, record and collaborate

with Moroccan musicians.

Gregorio went on to pursue

both his own musical projects

as well as fine art. Luis Paniagua

became a well-known sitar player

who also, these days, plays a

classical Greek lyre made by his

brother Carlos.

Eduardo began to focus on the

production of recordings. In

1994, he founded his own label,

Pneuma, which means "spirit"

in Greek. By early this year,

Pneuma's output had surpassed 120

cd's,

a pace of some eight to 10 each year in

a prolific, wide-ranging exploration of

music in medieval Spain, North Africa

and, increasingly afield, in the eastern

Arab world. For bringing so much of this

music to the broader public, the Academy

of Spanish Music has nominated Paniagua

three times for its Best Classical Musical

Artist award.

For Delgado, "Eduardo's work in recent

decades has been of enormous importance

for the dissemination and knowledge of

Andalusian music, not only in Spain, but

in Europe. His recordings include not the

new interpreters of this music, but

classical recordings of performers and

styles that have received little attention

in other previous labels. Thanks to Pneuma,

these recordings are now available."

|

|

"It's a joy to be able to do this work. Yet

I don't know why it entered me. I don't

know why I have this love of Arab

music and early music. I only know

that I love it," Paniagua says. |

One of Paniagua's first recording

quests is also his most ambitious,

a still-unfolding journey that, if he

completes it, will mark an unprecedented

feat: Initially under contract with

Sony, and later on Pneuma's label, he

has set out to record all 420 songs of the

13th-century songbook known as the

"Cantigas de Santa Maria," which was

compiled in Toledo under the patronage

of King Alfonso x.

These songs chronicling the miracles of the Virgin Mary are

a mosaic of the region's traditions, Paniagua

says, making them an exceptionally

rich source for exploring Spain's medieval

music. Not surprisingly, the "Cantigas"

are popular with early music ensembles worldwide.

Although no one knows for sure precisely

which instruments were originally

used to perform the "Cantigas," detailed

illustrations in surviving manuscripts

give a surprising amount of detailed

information. They also often depict

Arab and European musicians playing

together. Alfonso almost certainly had

Arab musicians in his court: Nine years

after his death, his son employed 27

salaried musicians, including 13 Arabs,

two of whom were women. Like other

early music ensembles around the world,

Paniagua's group, Musica Antigua, began

to experiment with Arab rhythms and

instruments in performances and recordings

of the "Cantigas," seeking a balance

between interpretive historical fidelity

and sounds that can please modern

ears, too.

As he continues to work through the

"Cantigas," Paniagua has also recorded

North African groups playing the classical

nubah suite music of Morocco,

Algeria and Tunisia, and joined with

other Spanish and Arab musicians to

play combinations of medieval period

and modern Middle Eastern instruments.

They recorded several popular nubat

and named their trans-Mediterranean

group Ibn Baya, after one of Paniagua's

most admired Andalusians: philosopher,

scientist, composer and musician Ibn Bajjah,

also known as Avempace, who lived

in the late 11th and early 12th centuries.

The years of study and practice that

Paniagua and his Spanish colleagues had

invested came to fruition in these recordings:

talented musicians, a perfect blend

of instruments, a careful choice of repertoire

and high production values. (See

"A Pneuma Sampler.")

"I learned a lot from the Ibn Baya

recordings," Paniagua says. "The music

of North Africa is a living tradition, not

fixed. It sounds different at home or at a

wedding. And the poetry is very important.

It's the expression of the music, and

they can change one bit of poetry for

another."

n Paniagua's home studio in suburban

Madrid, hundreds of musical

instruments from around the Mediterranean

fill two walls of floor-to-ceiling

display cases. A large collection of

lps and

books about the Middle East and its music

flank the others.

n Paniagua's home studio in suburban

Madrid, hundreds of musical

instruments from around the Mediterranean

fill two walls of floor-to-ceiling

display cases. A large collection of

lps and

books about the Middle East and its music

flank the others.

He picks up a medieval lap harp, a

two-winged psaltery made by his brother

Carlos from an illustration from the 13th

or 14th century. He begins to play an old

Andalusi tune from North Africa. A multiinstrumentalist,

Paniagua also plays the

qanun, the plucked zither of the Arab world

and Turkey. On both psaltery and qanun,

he explains, he deliberately uses simple

plucking techniques and a pared-down

ornamentation that he believes would have

been prevalent in medieval times.

Later, he plays an improvisation on

the Eastern European flute, the kawala.

Though he also plays the end-blown reed

flute of the Arab world called nay, Paniagua

chooses to use the kawala when he's

performing medieval Spanish music: It

sounds better to modern ears when playing

the scales of North Africa and medieval

Spain, he explains.

|

|

BIBLIOTECA MONASTERIO DEL ESCORIAL / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

|

A 13th-century illustration accompanying one of the

"Cantigas de Santa Maria" includes musicians in the court

of King Alfonso x. |

A frequent collaborator with Paniagua

is Wafir Sheikh el-Din, a Sudanese

singer and 'ud player living in Madrid

who brings his Arab background to many

of Pneuma's projects. An early member

of the popular world-music band from

southern Spain, Radio Tarifa, which

blended Spanish and Mediterranean

music, Sheikh el-Din was studying in

Madrid when he says he fell in love with a

recording by Calamus called "Splendours

of al-Andalus." He made contact with

Paniagua, who happened to be looking for

an 'ud player to join the Cantigas project.

Sheikh el-Din has worked with Paniagua

ever since on many recordings, touring

with him in the eastern Arab world.

"I love Eduardo's work," he says, "especially

as a producer, because he can take

scientific knowledge and turn it into an

actual experience. He knows how to put

something on the stage.

"I think the most important work

we do," he adds, "is the connection of

the three cultures—Jewish, Muslim and

Christian. This is the main dish for me,

because in my personal life, I dedicate

myself to make a connection with religion.

When we perform, we notice that

people are thirsty to find connections

between the cultures."

Paniagua's own thirst for the subject

has led Pneuma to produce cd's

exploring not only the three cultures of al-Andalus,

but also Gregorian and Catalonian chants,

Sephardic songs, songs about the famous

Battle of Arcos in 1195, the legend of El-

Cid and the legacies

of the troubadours.

Despite this musical range, Pneuma

recordings maintain a distinct graphic

style. This is where Paniagua the architect

comes in: He is deeply involved in the design of each

one, and the liner notes, which he writes

himself, are usually extensive enough to

require their own booklet.

The cd covers

and notes are all filled with abundant

period illustrations, many showing medieval

musicians. Most cd's

have their notes translated into both English and French.

"The music speaks for itself," Paniagua

says, "but what's really fascinating

is where it was found, where it comes

from, the history of it. Sometimes it

takes twice as long to do the texts as the

recordings, due to all the translations and research."

Alongside performing, recording

and producing, Paniagua's job with

Madrid's regional government connects

him to architecture much as he is

connected to music: He advises landowners in rural areas on

the restoration of old structures, especially

in villages and town centers; he catalogues

significant old buildings and tries to keep

them from being destroyed.

|

|

Crafted by Paniagua's brother Carlos

to resemble such instruments as the

one appearing on the cover of

Pneuma's 2009 catalog, above, this replica medieval 'ud is on

display in Granada at the Pabellón

de al-Andalus y la Ciencia. |

|

Indeed, some of Paniagua's most interpretive

recordings connect the music of

al-Andalus to its architecture.

The cd

"La Felicidad Cumplida" ("Perfect Bliss") sets

poetic inscriptions carved on the walls

of Seville's Alcázar Palace to traditional

al-Andalus melodies from North Africa.

It includes a song set to this builder's or

architect's prayer, which appears in 18

places in the Alcázar:

O my trusted Friend! O my Hope!

You are my Hope; you are my Protector!

Bless my work with Your Seal of Approval.

Similarly, the cd

"Mudejar Builders" celebrates the multicultural history

evoked by the Church of St. Martin at

Cuellar, built in the 12th century by

mudejars, Arabs who lived in the Christian

territories of Spain before 1492. The

Alhambra Palace in Granada, too,

inspired several Pneuma recordings

featuring the verses of poets whose

words are inscribed on its walls. One

incorporates the soothing sounds of

the Alhambra's fountains in the background,

while another evokes three

stories from American author Washington

Irving's beloved book Tales of

the Alhambra.

Paniagua has also delved into the

music of Islam. The cd

"Al Muedano" ("Muezzin") features several versions

of the adhan, or call to prayer, including

a stirring choral version recorded

in the chanters' hall of the Umayyad

mosque in Damascus. He has also

made recordings of the religious associations

in Tangier singing Arabic

poetry of al-Andalus.

Pneuma is a small shop: Paniagua

works calmly with his longtime

sound engineer Hugo Westerdahl

in the Axiom sound studio off

Madrid's bustling Plaza Santa Ana,

where locals sample tapas late into

the night. The two men are putting

the finishing touches on another

unusual project: a recording made

using instruments sketched by Leonardo

da Vinci but never before built.

Three artists from around the world

built prototypes, including a lightweight

paper organ, a mechanical bowed instrument

with a keyboard known as a viola

organista and a silver viola with a neck

in the shape of a horse's head. Paniagua

says their challenge is to eliminate the

mechanical sounds the instruments make

while being played and to soften some

harsh tones coming from the viola.

Then they turn to Paniagua's next project:

a duet between 'ud and sitar with Iraqi

'ud master Naseer Shamma, who runs

a music school in Cairo. Paniagua is also

putting final touches on the latest "Cantigas"

disks—one about Jesus and another

of women's "Cantigas" featuring Samira

al-Qadiri, a singer from Tetouan, Morocco.

Playing a track from this recording, Paniagua

points out how her vocal timbre and

delicate ornamentation produce a different

overall sound than one hears from

western vocalists. Though it was challenging

for the singer to learn the melodies by

ear, Paniagua seems delighted

to present another approach to

the music of medieval Spain to

his listeners.

|

|

Paniagua shows liner notes to

writer Kay Campbell. In some

cases, research for a Pneuma

recording, he explains, takes

more time than production of

the music. |

merican musician Bill Cooley recalls that it

was in the late 1990's that he

became fascinated with the

music of medieval Spain and came across

"Splendours of al-Andalus" by Calamus.

Although the music was compelling, he

says he was most intrigued by the blackand-

white photograph of instruments

that appeared on the back cover. "I used

to look at the photo with a magnifying

glass, wondering how the instruments

were made."

merican musician Bill Cooley recalls that it

was in the late 1990's that he

became fascinated with the

music of medieval Spain and came across

"Splendours of al-Andalus" by Calamus.

Although the music was compelling, he

says he was most intrigued by the blackand-

white photograph of instruments

that appeared on the back cover. "I used

to look at the photo with a magnifying

glass, wondering how the instruments

were made."

Inspired by the music and a growing

desire to learn to build medieval instruments,

Cooley traveled to Madrid to study

'ud with Wafir Sheikh el-Din, as well as

instrument-making. Sheikh el-Din soon

introduced him to Paniagua.

"I came here because of the work Eduardo does. It shows

on an international level what that means. He has created

a resource, not only for people in Spain, but internationally,

for people to study music that is no longer played so much

or recorded much. You can find other recordings of Andalusian

music from Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, but you have to go

there to find them. So what Eduardo's doing when he records

these traditional groups is very important."

As Paniagua reaches the halfway mark of his quest to record

all of the "Cantigas"—which he estimates will total 60

cd's

in the end—he says he feels "freer and less guided by outside

criticism, because the work is there. If something comes

together really well, all the elements work. It's a complex,

intuitive world. The more you learn about history, the better

you can step ahead with your interpretations. Yet this music

is always a thesis. It's something you propose to do. I can

never put my hands in the fire and say with certainty,

'This is the way it was done.'"

|

Kay Hardy Campbell

(www.kayhardycampbell.com)

lives near Boston, where she plays the

'ud and helps direct the annual

Arabic Music Retreat at Mount

Holyoke College. |

|

Photographer and writer

Tor Eigeland

(www.toreigeland.com)

has covered assignments around

the world for Saudi Aramco World and other publications, and has

contributed to 10 National Geographic Society

book projects. |