|

|

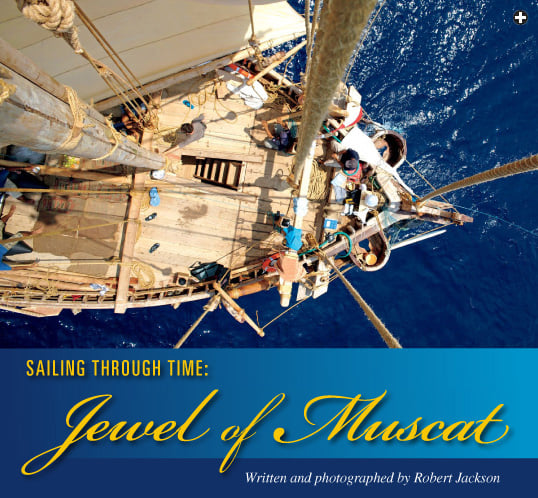

A view of the Jewel of Muscat's deck from the top of the mizzen mast: Every plank and board is held in place with coconut fiber. |

Towering swells lift us skyward, then drop us deep into their troughs as they roll beneath our hull. Occasionally,

waves strike us broadside with such force that compressed air from below rushes up through the hatches. Water pours

over the starboard gunwale, cascading across the deck and down the companionways—soaking everything and everyone

below. Holding fast to the rigging, crewmen stand straddle-legged at their stations against the pitching deck.

We are running eastward across the Bay of Bengal before 50-knot winds (92 kph, 60 mph), our lines taut as steel and the

single storm-sail stressed to the breaking point. Any mishap now will surely invite disaster. Deafened by the blast of

rain and spray against the hoods of our flapping raincoats, we hold on, hoping the 18-meter (59') ship will hold together.

Finally, after more than two hours of fury, the wind and rain begin to abate. Although the storm will batter us for two

more days, the worst is over. The Jewel of Muscat has triumphed in the greatest trial of her five-month voyage

across the Indian Ocean from Oman to Singapore.

Surviving a tropical cyclone is an impressive feat for any sailing vessel. But the Jewel of Muscat

is in a class of her own: She's a reconstruction of a ninth-century ce Arab ship,

and her planks and frames are entirely sewn together, making her success all the more remarkable.

|

|

Riding out a tropical cyclone in the Bay of Bengal proved the roughest test for the Jewel of Muscat. |

Several nights after the storm, I stand at her helm contemplating the immensity of stars that arch from horizon to

horizon. We are making only two knots (3.7 kph, 2.5 mph), in water so calm that it mirrors the light of every star,

and I have the sensation of flying through space. The only sounds are the slap of the water against the hull, muted

conversations in Arabic, the creaking of the deck and the chirping of a cricket in the coils of rope behind my feet.

It is June 2010, but the ship is a time machine, carrying us centuries into the past.

|

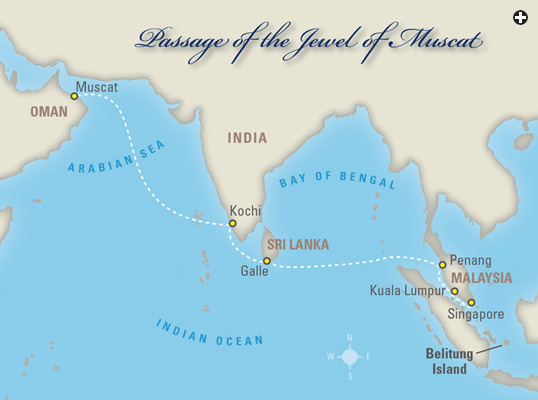

We had set sail from Oman's capital, Muscat, some three and a half months before, but our journey really began on an

ordinary day in 1998, when two divers searching for a new bed of sea cucumbers two kilometers (1.2 mi) off Belitung

Island, Indonesia, spied something much more valuable on the seafloor, some 17 meters (55') down. Clustered in a low

mound, half buried in sand, were stacks of Chinese pottery, large, heavily concreted jars and the eroded ends of wooden

beams. The divers had discovered the remains of a fully laden Arab merchant ship dating back some 1200 years. The

oldest shipwreck ever found in the Indian Ocean, it offered the earliest and most comprehensive evidence of direct

seaborne trade between the Arabian Peninsula and Persia in the west and China in the east.

|

|

When the storm caused a crack in the main mast, the crew splinted it with some of the spare rope

and wood that was carried on board for just such emergencies.

|

Excavation of the "Belitung wreck" revealed 60,000 pieces of ceramics and other artifacts. These included

the earliest intact examples of Chinese blue-and-white ware, a small but priceless collection of silver and gold

objects, a fine assembly of "green-splashed" ware and a bowl from Changsha in south-central China bearing

the inscription, "the sixteenth day of the seventh month in the second year of Baoli era"—that is,

826 ce. The nature of the cargo indicated that the ship had begun its homeward voyage

in the Chinese port of Guangzhou (Khanfu in Arabic). This fits in well with the findings of Robert Harding of Cambridge

University, who writes that the Chinese began to export high-quality ceramics to the Middle East during the Tang

Dynasty (618–907) and that Muslim merchants began their own voyages to China in 807.

Once fully loaded, the ship had embarked on a journey linking the world's two leading powers, the Tang Dynasty, with

its capital at Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an), and the Abbasid Empire (750–1258), ruled from Baghdad. The ship's

likely destinations: Siraf in southern Iran or Basra at the head of the Gulf. It was the longest maritime trade route

in history, stretching some 12,000 kilometers (7500 mi), until the Europeans arrived in the Indian Ocean in the

15th century.

The Belitung wreck and its cargo offered an unprecedented opportunity for historians to discover more about early

trade between the Middle East and Asia, as well as the shipbuilding and navigation of the period. In 2005, recognizing

that the wreck was an immensely important archeological discovery, the government of Singapore purchased for $32 million

the entire assemblage of artifacts from the New Zealand company that had done the initial salvage work and immediately

began meticulous analysis of the finds.

|

|

|

alessandro ghidoni |

|

Top: Captain Saleh al-Jabri uses one of the ship's several kamals, which helped navigators for millennia

determine latitude using star altitudes. (Until the 18th century there was no way to determine longitude.)

"This voyage was my greatest challenge in 25 years at sea," he says. Above: The strength of the ship depended

on the integrity of its stitching. Every seam was sewn and packed with coconut-fiber wadding and every

drill-hole was sealed using a traditional Indian Ocean putty of chalk, resin and fish oil. |

Belitung Island lies about 620 kilometers (300 mi) southeast of Singapore, which itself is on the southeast side of

the Malacca Strait—long a key passage for trade. After purchasing the cargo, Singapore opened diplomatic and

academic channels to take full advantage of the cultural, historical and political opportunities created by the

discovery. The government's primary partner in this endeavor was the Sultanate of Oman, on the southeastern corner

of the Arabian Peninsula, a country with an illustrious maritime heritage.

Oman's Ministry of Foreign Affairs agreed in 2008 to fund construction of a ship based as precisely as possible on

the Belitung wreck. Sultan Qaboos bin Sa'id, the ruler of Oman, took a keen personal interest in the project,

naming the vessel the Jewel of Muscat and decreeing that, once built, the ship would be a gift from Oman

to the people of Singapore. In response, Singapore agreed to construct a special museum to display it.

To ensure that the vessel met the highest standards of authenticity and quality, the Omanis invited Australian

maritime archeologist Dr. Tom Vosmer, the world's leading authority on the history of Arab shipbuilding, to head

the construction team. They aimed not only to reconstruct a ninth-century Arab ship, but to document its sailing

characteristics and durability by sailing it across the Indian Ocean. Both tasks were fraught with challenges.

Attempting to construct an authentic, seaworthy ninth-century ship in the 21st century was certainly daunting.

Unfortunately for modern historians—but to the great credit of traditional shipwrights, who built their

vessels entirely by eye—virtually no plans, records or written descriptions of Arab shipbuilding exist from

earlier than the 20th century. A serious design flaw that a shipwright would have spotted instantly 12 centuries

ago might not be apparent even to the most knowledgeable modern naval architect today, with potentially disastrous

consequences at sea.

|

|

Beginning in October 2008 in the coastal village of Qantab, southeast of Muscat, Oman, the team of

shipwrights and archeologists took 17 months to build the Jewel of Muscat.

|

The Belitung wreck was helpful to some extent, but only about 20 percent of the original vessel remained

sufficiently exposed on the seafloor for excavators to examine. Close analysis of the wreck revealed that its

timbers were predominantly Afzelia africana, a dense hardwood that flourished along the East African

coast in the ninth century and was ideal for shipbuilding. In addition, every structural component of the

vessel—frames, through-beams and planks—was entirely stitched together in the manner of traditional

western Indian Ocean ships dating back at least two millennia. The planks were joined edge to edge, carvel-style,

and cross-stitched directly through the planking, with wadding on both sides of the seam. These characteristics

assured Vosmer that the Belitung wreck was of northwest Indian Ocean provenance.

|

|

alessandro ghidoni |

|

|

alessandro ghidoni |

|

Top: Built hull first, the ship required more than 20 tons of wood, shaped by hand. Above: Each

hull plank had to be steamed to fit it to just the right curve. "We were in awe of the people who,

over a thousand years ago, felled, transported and processed these massive [Afzelia] trees," says

Tom Vosmer. "The labor intensity was staggering." |

Missing information about its design and structure had to be gleaned or inferred from historical texts,

iconography and extant examples or photographs of Arab sewn-plank boats. This information was analyzed and

integrated using the latest naval-architecture software. Ultimately, Vosmer and fellow Australians Nick Burningham

and marine archeologist Dr. Mike Flecker, the excavator of the Belitung wreck, arrived at a computerized design

that reasonably incorporated the evidence they had on hand—with the final result resembling a large-scale

variation of an indigenous Omani boat known as a battil.

Professionals in Britain built two approximately 1:10 scale models of the ship based on this design, and Vosmer

tested them—one in a towing tank and the other in a wind tunnel—at Southampton University. Ship design

has developed gradually over thousands of years, by a sometimes painful process of trial and error, and these

tests were crucial to the project's success.

Investigators found design weaknesses in two areas and rectified them before ever setting sail. First, they altered

the shape of the stern so that it curved less abruptly, reducing drag and increasing efficiency. Second, the distance

between the main mast and the mizzen (or rear) mast was increased because the original design would have resulted in

the mizzen sail "shadowing," or blocking the wind from the mainsail. This added distance enabled crewmen to

work the two sails together more efficiently.

Vosmer's handpicked team of highly skilled Omani and Indian shipwrights and carpenters,

and Italian and American maritime archeologists, began building the ship in October 2008 in the Omani coastal village

of Qantab, just southeast of Muscat. For the next 17 months, the men endured intense heat and tackled successive design

challenges as they worked to rediscover and put into practice the knowledge and techniques employed by ninth-century Arab

shipbuilders. Given the paucity of documentation, constructing the Jewel of Muscat required a constant and

exhausting cycle of theorizing, experimentation and analysis.

Construction also required 15 tons of Afzelia africana (harvested in Ghana, since the tree no longer grows on

the East African coast), five tons of teak and several tons of other types of wood. "We were in awe of the people

who, over a thousand years ago, felled, transported and processed these massive [Afzelia] trees," Vosmer

said. "The labor intensity was staggering." To tie it all together, the construction crew used 130 kilometers

(80 mi) of handcrafted coconut-fiber rope, hundreds of liters of coconut and shark oil to waterproof the planks and the

stitching, and impressive amounts of skill, determination and enthusiasm.

|

In the interest of authenticity, crewmen used traditional hand-tools, including saws, adzes, chisels, hammers and such

simple measuring devices as the qalam, used to mark parallel lines on planks. Among the few concessions to

modern technology was the use of electric drills rather than the traditional migdah, the hand-powered Arab

bow-drills: The latter are ingenious and highly effective devices, but they proved 10 times slower than electric drills.

Given that 37,000 holes had to be drilled in the hull to accommodate the stitching, and that the builders were working under

a tight deadline to catch the winter monsoon winds, the decision to compromise was understandable.

A key construction challenge that Vosmer and his team had to resolve was how to shape the planking. Like all Arab ships

of its time, the Belitung vessel was built hull first. This is the opposite of traditional western construction techniques,

in which the frame is built first and the planks are then bent and fixed to the ribs.

The hull-first approach requires that the planks be twisted or curved prior to being attached to one another.

After numerous experiments, the team built a wooden steam box that, in two hours, rendered the five- to seven-meter-long

(16 1/2 to 23') planks flexible enough to be fitted into their appropriate place on the hull. The builders had to carry

out the task quickly because the wood remained pliable for only a few minutes after coming out of the box. Despite this,

the system worked, and as each level of planking was added, the graceful form of the hull emerged.

|

|

At mealtimes, the 17-man crew from nine nations sat on the deck around communal trays and ate simple

food, such as rice and dried fish prepared in a traditional wooden cook-box, or matbakh.

|

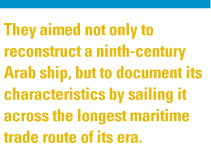

Binding the planks together was as important as properly shaping them. Once the holes were drilled in the planks, they

had to be sewn together with precision, for the strength of the ship depended entirely on the integrity of the stitching.

Inspection of the Belitung wreck revealed that a row of coconut-fiber wadding had been added to each side of the seams.

Then it was stitched over with rope.

|

|

|

eric staples |

|

Top: Accommodations stayed true to ninth-century standards—with the exception of plastic sheeting

to deflect leaking seawater. Above: Jewel was built with both a pair of tiller-steered

quarter-rudders and a rope-driven central rudder: In the ninth century, the former represented a

traditional method while the latter was new technology.

|

At first, this system appeared to render the stitching more vulnerable to abrasion. And in fact, centuries later, Arab

shipbuilders had indeed done away with exterior wadding and instead countersunk the outside stitches to reduce the dangers

of abrasion, and perhaps reduce drag. But the builders of the Jewel of Muscat remained true to the older method,

and the team soon learned its advantages. For example, the exterior wadding added cushioning to the stitches and the seam

itself and, once saturated with fish oil, it provided a thicker barrier against seawater.

The rope workers operated in pairs, one inside the hull and one outside. Using the simplest of tools, including a large

wooden marlinspike and a mallet, and small wooden plugs to temporarily lock the stitches in place, one man threaded cordage

through the holes drilled in the planks, applied just the right amount of tension, and then passed the rope over the wadding

and through the hole to his partner on the other side. The level of tension on the rope was critical: too much and it would

snap; too little and the seal between the planks would leak. When stitching was complete, each hole was carefully plugged

with densely wadded coconut fiber, and then sealed with a traditional Indian Ocean putty made from chalk, resin and fish oil.

Once the challenges of reconstructing the Belitung vessel were met, the second phase of the project commenced. On February

16, 2010, the Jewel of Muscat glided out of Muscat's Mutrah harbor and into the open ocean, her 17-man multinational

crew led by Omani captain Saleh al-Jabri. During our slow, hot passage to India and beyond, we gradually embraced the arduous

but simple rhythm of life at sea.

At mealtimes, we sat on the deck around communal trays and ate simple food such as rice and dried fish prepared in a

traditional wooden cook-box, or matbakh. When the winds dropped to near zero and the temperature and humidity

soared, we learned to accept our helplessness in the face of nature. We marveled at majestic sunsets and rejoiced—as

have all sailors over the centuries—at the sight of dolphins playing off our bow. We also discovered that despite

differences in language and culture and the hardships of cramped space, limited sleep and enervating heat, we could unite

as a crew and work toward a common goal. We hailed from nine nations—India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, Italy,

Australia, the us and the uk, as well as Oman—but we

learned to respect each other's talents and experiences, and appreciate the role that each man played in the success of

the voyage.

|

|

A crewmember wraps protective baggywrinkle on the manila-fiber rigging where it might wear holes

in the sails.

|

Among our many tasks at sea was documenting the effectiveness of the ship's most essential features. For example, a key

question Vosmer and his team had faced during the Jewel of Muscat's design and construction was what type of

sails she would carry. The Belitung wreck left no evidence of rigging, so Vosmer delved into early texts and iconography

for clues. His research suggested that the Belitung ship would have carried square rather than triangular lateen sails.

This ran counter to the generally held belief that Arabs used lateen or settee sails—a lateen sail with a small

section of the front corner cut off—beginning in the fourth century bce.

In the 15th century ce, Vosmer noted, the famous Arab mariner Ahmad ibn Majid wrote that

the constellation Pegasus, which has the general shape of a square, resembled the proportions of an Indian Ocean sail.

Furthermore, numerous drawings of Indian Ocean ships dating from the mid-12th through the 16th century depict Arab ships

with square sails. Notably, several show a crow's nest atop either the main or mizzen mast, a feature impossible on a

lateen-rigged ship because it would prevent switching the yard from one side of the mast to the other when the ship tacked

or wore across the wind.

Once at sea, we discovered just how practical square sails were. Not only were they easier to handle when tacking or

wearing, but—when properly trimmed—we could sail as close as 51 degrees to the apparent wind (the combination

of "true wind" and the wind created by the forward motion of the ship). This meant that under the right

conditions we could "harness" more wind and sail with greater efficiency and speed than anticipated—perhaps

one of the reasons square sails endured for so long on Indian Ocean ships.

Another critical question concerned the type of steering system the Jewel of Muscat would use. A particularly

fascinating aspect of the Belitung ship was that it was built during a time of technological transition in maritime

design. For millennia before the ninth century, ships used quarter rudders—long rudders fixed to each side of the

hull—to steer. Each was controlled by its own tiller. When the ship was on a starboard tack (i.e., with the wind

coming from the right), the helmsman used the port rudder, and vice versa. But around the ninth century Arabs began

fitting a single, central rudder to the sternpost of their ships.

|

|

A spectacular dawn off the Malaysian coast heralded Jewel's approach to the Malacca Strait, the world's busiest

shipping lane. |

Sailors are understandably conservative when it comes to innovation, tending to stick to what's tried and true, and

textual and iconographic evidence shows that the complete transition to this new type of rudder took about three

centuries. So builders outfitted the Jewel of Muscat with both systems and, when used properly, they complemented

each other quite well—perhaps explaining why ancient mariners waited so long before fully switching over. In very

light winds the central rudder proved most effective, while in light to moderate winds the quarter rudder worked best.

In high wind and rough seas, we often used both systems simultaneously, with the median rudder offering an additional

degree of control.

Perhaps the most important technical revelation from the voyage was that, contrary to most early European observations,

sewn-plank ships can be remarkably strong. Writing in the 15th century about sewn ships from Hormuz in Persia, Marco

Polo stated:

The vessels built at Ormus are of the worst kind, and dangerous for navigation, exposing the merchants and

others whomake use of them to great hazards. Their defects proceed from the circumstance of nails not being employed

in the construction... [T]hey are bound, or rather sewed together, with a kind of rope-yarn stripped from the husk of

Indian nuts [coconuts]….

Our experience contrasted sharply with this claim. Indeed, the Jewel of Muscat proved to be structurally

stronger than the designers anticipated. She endured numerous severe storms during the voyage—especially in

the Bay of Bengal—but suffered no damage to her hull. She was also subjected to the modern indignities of being

towed into and out of ports, bumped and jostled by heavy tugboats while docking, and exposed to pollutants in congested

harbors, yet she remained unscathed.

|

Despite our commitment to maintain as much historical authenticity during the Jewel's voyage as had been

applied to her construction, we were compelled for safety reasons to navigate with the greater precision afforded by

a gps—using satellites rather than stars for direction. This device requires

little skill to use, and we were constantly humbled by how well early sailors had navigated without it. Arab mariners

began to use a compass in the 13th century, not long after it had become standard equipment for western ships. Prior

to that, they employed a simple but ingenious instrument called a kamal—basically a rectangle of wood

to which a string with fixed knots is attached. Held at arm's length, with its lower edge on the horizon, the kamal

was used to measure the altitude of a given star (especially the Pole Star) from the horizon and thus determine

latitude. They did not, however, have a reliable method for determining longitude.

The remarkable 15th- and 16th-century texts of the great Arab navigators Ibn Majid and Sulaiman al-Mahri explain how

ancient sailors observed the sun, currents, wind, sea color and sea life to help them navigate by day. They also

reveal that the navigators' astonishingly detailed knowledge of the heavens was their primary means of navigation

by night. Dr. Eric Staples, an American maritime historian and a member of the crew, studied these documents prior

to and during our voyage. To learn as much as possible about the use of the kamal, and to compare modern measurements

with those found in the old texts, he employed several versions of the device to create a database of the altitudes

of 14 stars and constellations traditionally used by Arab navigators.

|

|

138 days after setting out from Oman, the Jewel of Muscat arrived in Singapore, where she has been

donated for permanent display at the Maritime Experiential Museum. |

Using a kamal takes considerable practice even under ideal conditions, but it won't work on cloudy nights or during

storms. Fortunately, our voyage proceeded more peacefully after the tempests of the Bay of Bengal, so we were able to

take more regular star readings. Day after day we glided eastward toward Penang, Malaysia, our penultimate port of

call, and then south through the Straits of Malacca—taking care to avoid Sumatran pirates and the supertankers

that ply the busiest shipping lanes in the world.

Finally, 138 days after setting out, we sailed into Singapore's harbor to a rapturous welcome by thousands of well-wishers,

colleagues and friends, followed by receptions hosted by Omani and Singaporean dignitaries, and the official handover

of the Jewel of Muscat by Captain al-Jabri to Singaporean President S. R. Nathan.

"This voyage was my greatest challenge in 25 years at sea, but it was also incredibly rewarding in terms of what

we learned about Arab maritime history," Captain al-Jabri said.

Amid all the chores involved in readying the ship for arrival, there was time to reflect on the meaning of the voyage.

It had been a grand adventure, and we had learned a great deal about ancient Arab ships and sailing. But, above all,

our experiences had kindled an intense respect for the knowledge, skills and courage of the ancient Arab mariners in

whose wakes we had sailed.

In the ninth century, without a compass but with a hard-won understanding of the sea, the winds and the stars, they

crossed the vastness of the Indian Ocean, uniting people and nations in commerce, faith and friendship. This was the

real legacy of the Jewel of Muscat, one that she will continue to share with her visitors for many

generations to come.

|

Robert Jackson (jacksonr546@gmail.com) teaches history at The

American International School of Muscat in Oman. He is the author of At Empire's Edge: Exploring Rome's Egyptian

Frontier (Yale, 2002). His current research focuses on the early history of trade in the western Indian Ocean. |