|

|

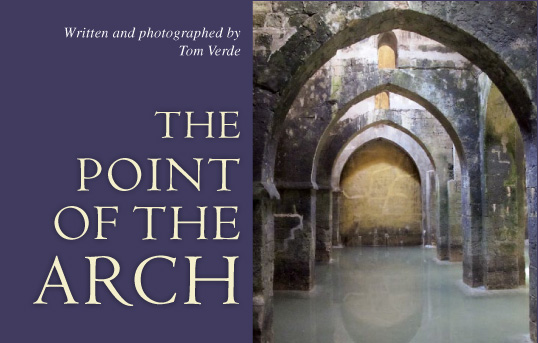

The pointed arches at the Cistern of Ramla were commissioned in 789 ce by the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid.

|

bove ground, the Eighth-century Cistern of Ramla, about an hour southeast of Tel Aviv, doesn't look like much: long rows of

whitewashed humps of rubble, like raised garden beds, dotted with holes through which one can drop a bucket on a rope.

Even its Arabic name, Bir al-'Aniziya ("Pool of the Goatherds"), undersells it. With a closer look, however, its

importance quickly becomes evident, as well as the reason it is also known as "The Pool of Arches."

bove ground, the Eighth-century Cistern of Ramla, about an hour southeast of Tel Aviv, doesn't look like much: long rows of

whitewashed humps of rubble, like raised garden beds, dotted with holes through which one can drop a bucket on a rope.

Even its Arabic name, Bir al-'Aniziya ("Pool of the Goatherds"), undersells it. With a closer look, however, its

importance quickly becomes evident, as well as the reason it is also known as "The Pool of Arches."

"Watch your head," the caretaker advised me, tapping the low ceiling of a lichen-crusted stairwell that led down to the

cistern's chamber, flooded with cloudy, blue-green water. Shafts of sunlight streaming through the access holes ricocheted off

the water's surface, casting wriggling reflections on a cavernous network of arches, each one elegantly curved upward from its

pillars to a pointed apex. Technically known to art historians and architects as "ogival" or simply "pointed"

arches, these were built in 789 ce, making them among the oldest such arches in Islamic architecture,

and their use here, at that time, signaled a turn in the history of architecture.

The change was both esthetic and structural. Compared to its predecessor—the semicircular "Roman arch"—the

pointed arch gracefully tapers at a variety of angles, and its greater height admits more light. Structurally, a pointed arch can

generally support up to three times as much weight as a Roman one, and was one of the key architectural features that allowed the

builders of western Europe's great medieval cathedrals to raise their walls and ceilings to dizzying heights, thereby creating the

vertiginous Gothic style. Those builders owed much to Ramla's cistern and to other structures throughout the Arab world, where the

pointed arch made its appearances centuries before it entered the architectural lexicon of Europe.

But how? How did the soaring interiors of Chartres, Sens, Salisbury and dozens of other Gothic buildings descend from what was

essentially a flooded basement in a sun-baked Arab town?

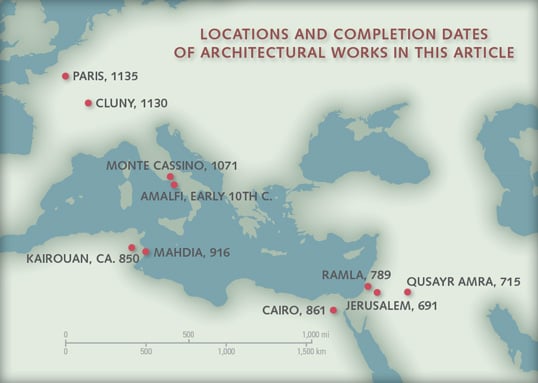

To answer that question, I tracked the pointed arch across five countries and as many centuries—a journey that began at

the trail's end, in the city where Gothic architecture was born: Paris.

don't mind being shot at" is how Alistair

Northedge summarized his dedication to the pursuit of archeological treasures in remote and sometimes dangerous corners of Iraq,

Afghanistan and other political hotspots across the Middle East. I met him in the comparatively peaceful setting of his office at

the Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, adjacent to Paris's famed Bibliothèque Nationale. Tracking down the origins of the

pointed arch would be tricky, Northedge told me, because there is disagreement over whether or not some of the oldest examples—such

as the sixth-century Great Arch of Ctesiphon at the Sassanian palace of Taq-e Kisra in northern Iraq, or the equally old Byzantine

church at Qasr ibn Wardan in Syria—are true pointed arches or merely parabolas, precursors to the pointed arch.

don't mind being shot at" is how Alistair

Northedge summarized his dedication to the pursuit of archeological treasures in remote and sometimes dangerous corners of Iraq,

Afghanistan and other political hotspots across the Middle East. I met him in the comparatively peaceful setting of his office at

the Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, adjacent to Paris's famed Bibliothèque Nationale. Tracking down the origins of the

pointed arch would be tricky, Northedge told me, because there is disagreement over whether or not some of the oldest examples—such

as the sixth-century Great Arch of Ctesiphon at the Sassanian palace of Taq-e Kisra in northern Iraq, or the equally old Byzantine

church at Qasr ibn Wardan in Syria—are true pointed arches or merely parabolas, precursors to the pointed arch.

|

|

hemis / alamy |

|

The gentle point in the arch at Qusayr 'Amra, which dates from 715, may have been as much a decorative device as a structural one.

|

"You can see some early doorways, for example, where the arch is pointed," Northedge observed, "but I'm not sure

these could be described as a deliberate esthetic, whereas it's clear that it does become a deliberate esthetic in the Umayyad

period in the first half of the eighth century."

In Northedge's estimation, some of the earliest instances of the pointed arch are in Jordan's famed "Desert Castles" such

as Qasr al-Kharanah and Qusayr 'Amra, built in 710 and 715, respectively, in what was then Umayyad-ruled Syria.

|

|

A pointed arch, right, can support up to three times as much weight as a semicircular arch, left.

|

"The [pointed] arches there are quite slight, but you can see that they are composed of two different arcs with centers that

are crossed over," he explained. Whereas a rounded arch has a single center, a pointed arch has at least two. The distance

between the centers determines the angle at which the two sides meet at the arch's apex—its "pointiness." Good

old-fashioned grade-school geometry helps to illustrate: Imagine a drafting compass, with the spike placed midway on a straight

line. Moving the pencil from one end of the line to the other produces a semicircular arc with a single center. But moving the

spike to a spot to one side of the midpoint and drawing an arc, then moving the point to the other side of the midpoint and drawing

a second arc creates two arcs that intersect: a pointed arch.

While rounded arches are unquestionably sturdy enough for countless Roman aqueducts and triumphal arches, they weaken with height,

because they direct the weight they support outward, toward the walls. The higher the arch, the stronger and thicker the walls need

to be, and walls could only be so thick before becoming ridiculously impractical and expensive. Pointed arches, however, direct

much of the thrust of weight downward, toward the ground, and they can thus support much thinner, higher walls.

That the pointed arch indeed traveled from East to West is hardly unknown to art historians, archeologists and architects. In the

words of the famed English architect of the late 17th and early 18th century, Sir Christopher Wren, the designer of St. Paul's Cathedral

in London, "This we now call the Gothic manner of architecture…. I think it should with more reason be called the Saracen

[Arab] style…. If any one doubts of this assertion, let us appeal to any one who has seen the mosques and palaces of Fez or

some of the cathedrals in Spain built by the Moors."

Generally dismissed at the time, Wren's insights were vindicated by later architectural historians, including W. R. Lethaby (1857-1931),

author in 1904 of Medieval Art, one of the first art-history textbooks to be used on college campuses. "There is much more

of the East in Gothic, in its structure and fibre, than is outwardly visible," Lethaby wrote. "It is not generally realised in

how large a degree the Persian, Egypto-Sarecenic and Moorish forms are members of one common art with Gothic."

The speculation that it was Crusader knights, returning from the East, who introduced knowledge of the pointed arch to Europe was a

popular outgrowth of this view. But the theory had its skeptics, including an eccentric Oxford student by the name of T. E.

Lawrence—later known as "Lawrence of Arabia"—who concluded in his 1908 undergraduate thesis that there was

"no evidence" that Crusaders "borrowed anything great or small, from any fortress which [they] saw in the Holy Land."

|

Among the earliest modern proponents of the theory of the pointed arch's Eastern origins was the redoubtable K. A. C. Creswell.

Born in London in 1879, Creswell was the American University in Cairo's first professor of Islamic art and architecture, and he is

generally considered a founding father of the discipline. His multivolume Early Muslim Architecture and equally ponderous

Muslim Architecture of Egypt occupy nearly a meter of shelf space. A draftsman by training, Creswell conducted his research

with an engineer's eye, photographing, cataloging and painstakingly measuring monuments from Egypt to the Euphrates. In his opinion,

"the evolution of the pointed arch" could be determined "by the gradual separation of the two centres." Charting

this evolution by comparing the fractional differences between the spans of various arches throughout the Middle East, he concluded

that the pointed arch was "of Syrian origin" and that "no European examples are known until the end of the eleventh

or the beginning of the twelfth century."

Research such as Creswell's is the best evidence historians have to go on, said Northedge, since the history of the arch in the Arab

lands is written exclusively in stone. "They [early Muslim architects] left no written records of their architecture," he sighed.

From Northedge's office, it is a short distance to the place where the masons of Europe's great Gothic cathedrals took their first

cues from the pointed arches, and the overall design, of the abbey church of St. Denis, famed both as the birthplace of Gothic

architecture and as the home of the man who served as its midwife, Abbot Suger.

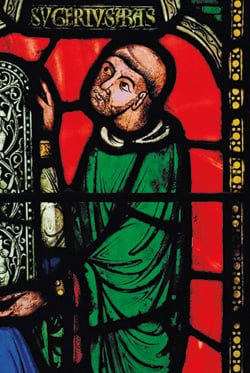

|

|

the art gallery collection / alamy |

|

For Abbot Suger of St. Denis in Paris, the pointed arch served both engineering and philosophy. An image of the abbot, above,

appears among the many stained-glass windows that illuminate the abbey church of St. Denis, below.

|

orn in 1081, Suger seemed destined for life at

St. Denis, where he was deposited at age 10 by his impoverished family as an "oblate"—essentially a human donation.

Educated at the abbey alongside the future King Louis vi, Suger became abbot in 1122. By then, the crumbling, eighth-century abbey

church was in dire need of both repair and expansion. In 1135, Suger began a building program, in league with architects whose names

have been lost, that was to transform the church's dim Romanesque interior into something brightly illuminated, airy and utterly new.

His design brought together for the first time what became the prime elements of Gothic architecture: pointed arches, the flying

buttresses that allowed the arches to support still more weight and ribbed vaulting, another eastern innovation. The result was a

jaw-dropping interior with soaring ceilings and gravity-defying walls composed of more stained glass than stone. Sunlight streaming

through these windows bathed the vast interior in a "crown of light," as Suger described it, and played a symbolic,

theological role in the abbot's overall architectural scheme.

orn in 1081, Suger seemed destined for life at

St. Denis, where he was deposited at age 10 by his impoverished family as an "oblate"—essentially a human donation.

Educated at the abbey alongside the future King Louis vi, Suger became abbot in 1122. By then, the crumbling, eighth-century abbey

church was in dire need of both repair and expansion. In 1135, Suger began a building program, in league with architects whose names

have been lost, that was to transform the church's dim Romanesque interior into something brightly illuminated, airy and utterly new.

His design brought together for the first time what became the prime elements of Gothic architecture: pointed arches, the flying

buttresses that allowed the arches to support still more weight and ribbed vaulting, another eastern innovation. The result was a

jaw-dropping interior with soaring ceilings and gravity-defying walls composed of more stained glass than stone. Sunlight streaming

through these windows bathed the vast interior in a "crown of light," as Suger described it, and played a symbolic,

theological role in the abbot's overall architectural scheme.

|

|

John kellerman / alamy |

"The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material and, in seeing this light, is resurrected from its former

submersion," he observed. In other words, light served a mystical purpose, elevating the earthbound human mind and soul closer

to the Divine. This was a belief first articulated by the Neo-Platonists of late antiquity, whose teachings Suger admired, particularly

those of the fifth-century Syrian Christian theologian known as Dionysius the Areopagite, who viewed God's presence "as fontal

ray, and stream of light … shining upon every mind." Two centuries later, a similar metaphor was revealed in the Qur'an

(24:35): "God is the Light of the heavens and the earth. The parable of His light is as if there were a niche and within it a

lamp: the lamp enclosed in glass: the glass as it were a brilliant star…. Light upon Light! God doth guide whom He will to

His light."

Like his philosophical views, Suger's designs for St. Denis had deep roots. In his biography of Louis vi,

he left a clue as to where he may have picked up the inspiration for his church: It was during a mission for the king to Cluny

Abbey, in southern Burgundy. The year was 1130, just five years before work began at St. Denis.

he trip from Paris to Cluny, which probably

took Suger a little more than a week on horseback, took me about four hours by train. Nonetheless, I still arrived about 200

years too late. A casualty of the anti-religious fervor of the French Revolution, much of the abbey was dismantled in the late

18th century and sold off, stone by stone, to local builders. Yet Cluny's renown still attracts visitors, just as it did when

it was medieval Europe's largest church and the headquarters of the powerful and influential Benedictine suborder of Cluniac

monks.

he trip from Paris to Cluny, which probably

took Suger a little more than a week on horseback, took me about four hours by train. Nonetheless, I still arrived about 200

years too late. A casualty of the anti-religious fervor of the French Revolution, much of the abbey was dismantled in the late

18th century and sold off, stone by stone, to local builders. Yet Cluny's renown still attracts visitors, just as it did when

it was medieval Europe's largest church and the headquarters of the powerful and influential Benedictine suborder of Cluniac

monks.

|

|

At the time of Suger's visit in 1130, Hugh of Semur's 30-meter arches at Cluny Abbey numbered more than 200.

|

Like St. Denis, Cluny had a creative and ambitious abbot, Hugh of Semur, and his renovations of the abbey known to historians

as Cluny iii began in 1088 and continued after his death until 1130—the year of Suger's

visit. While most of Cluny iii is gone, bits and pieces survive, with help from restorers, including several 30-meter- high

(nearly 100') pointed arches that played a crucial role in the story of the arch's journey from East to West.

"Here you can see the way that the arches opened up the church and made it full of light," said my guide, Matthias

Mai, as we entered. A series of clerestory windows in the exterior walls, together with round "bull's-eye" windows

in addition to the arches, admitted so much light that the effect was, as Abbot Hugh's contemporary biographer wrote, "a

place where the dwellers on high would tread."

My gaze followed the trajectories of the arches up to their clearly distinguishable pointed apexes. At the time of Suger's

visit, there were some 200 such arches lining the nave, side aisles and transept. The impact could not have been less than

stunning.

Today, flat-panel video screens throughout the abbey offer tantalizing computer-generated views of what he may have seen:

a church not yet fully Gothic, but clearly departed from the Romanesque.

"Abbot Hugh was one of the great builders of all time," the driving force behind "[t]he expansion of Cluny

into the Ile-de-France, where the admirably organic and articulated Gothic style arose," wrote the late art historian

Kenneth J. Conant, who made the study and excavation of Cluny his life's work.

So if Cluny's pointed arches inspired Suger, and thereby all of Gothic architecture, how had Hugh come to know of them?

"He understood engineering and knew what he was doing," said Mai. "He was one of the most educated and

intelligent men of his time."

And well traveled, too. In 1083, five years prior to renovating Cluny, Hugh visited an Italian abbey whose abbot just

happened to have a taste for Near Eastern architecture: the Benedictine Abbey of Monte Cassino, about 130 kilometers

(80 mi) southeast of Rome.

he World War ii

-era mortar shells, bullet cartridges and battered helmets on display in the lobby of my hotel didn't quite square with its

name, Hotel la Pace (Peace Hotel). They were, however, fitting reminders of the Battle of Monte Cassino, when the famous abbey,

looming above the town on a solitary, rockbound hill, was leveled by Allied bombs as a suspected German stronghold. (A tragic

mistake: It wasn't.) That marked the fifth time Monte Cassino had been attacked and destroyed, following Lombards in 589,

Muslims in 884, Normans in 1030 and an earthquake in 1349.

he World War ii

-era mortar shells, bullet cartridges and battered helmets on display in the lobby of my hotel didn't quite square with its

name, Hotel la Pace (Peace Hotel). They were, however, fitting reminders of the Battle of Monte Cassino, when the famous abbey,

looming above the town on a solitary, rockbound hill, was leveled by Allied bombs as a suspected German stronghold. (A tragic

mistake: It wasn't.) That marked the fifth time Monte Cassino had been attacked and destroyed, following Lombards in 589,

Muslims in 884, Normans in 1030 and an earthquake in 1349.

Thus, there are even fewer remains here than at Cluny, aside from some decorative 11th-century floors, a Roman-era tower

and a chapel dedicated to St. Benedict, the founder of both the abbey and the most powerful monastic order in medieval

Europe. After World War ii, although the abbey was completely restored in the Baroque style

of its last incarnation, bits and pieces of the medieval building survived as traces of its architectural connections to

the East. The aforementioned decorative floors, for example, are laid out in colorful, geometrically random Cosmatesque

patterns—patches of squares, diamonds and hexagons—that were modeled on Byzantine floor mosaics in Syria,

Palestine and Egypt. The massive, paneled bronze doors of the main church, etched with the titles of the abbey's vast

land holdings, dependencies and donors, were custom-made in Constantinople at the behest of abbot Desiderius, who renovated

Monte Cassino between 1066 and 1071. As Europe's leading center for manuscript production and the headquarters of the Benedictine

order, the abbey was then at its zenith of influence and wealth. The worldly and well-traveled Desiderius could thus afford

to import more than just exotic building material from the East. As abbey librarian Leo of Ostia noted in his contemporary

account of the renovation, Desiderius "sent envoys to Constantinople to hire artists who were experts in the art of

laying mosaics and pavements" as well as working in "wood, alabaster and stone."

Considering the geographic origins of these artisans, Conant and others have suggested that there may well have been Muslims

among them. The presence of Muslim engineers and masons in the medieval work crews of the Christian West was not unheard of.

During the Crusades and the Christian reconquista of Muslim Spain, many Muslim prisoners of war ended up in France,

Rome and Constantinople, as the late scholar John H. Harvey observed.

|

|

Though Leo of Ostia wrote of the "slightly pointed arches" on the portico of the embattled abbey of Monte Cassino,

above, they have not survived. Remaining floor tile decoration, below, nonetheless testifies to the stylistic influences,

if not the actual handiwork, of masons and artisans from the Levant.

|

|

"Among the prisoners there must have been a substantial body of Moorish military engineers," Harvey wrote, "and

it may be supposed that the victors would make use of their knowledge and their improved techniques." According to a

Welsh chronicle, one prisoner even rose to become royal architect for England's King Henry i: a captive "from the

land of Canaan, of the name of Lalys, a man eminent in the art of masonry, who constructed the most celebrated monasteries,

castles, and churches in the country…and taught the art to many of the Welsh and English."

Whether or not the renovations carried out by Desiderius's imported craftsmen—Muslim or otherwise—included

pointed arches is still a matter of debate among scholars. Conant believed they did. On a visit to the abbey before World War

ii, he noted the presence of pointed arches dating to the Middle Ages in a side chapel.

He further speculated that Monte Cassino served as the model for the church of St. Angelo in Formis in Capua, also built

by Desiderius, which features pointed arches in its entryway. Putting aside doubt for many is Leo of Ostia's account,

which described the porticoes of the main church as having fornices spiculos ("slightly pointed arches").

Leo also left clues as to when and where Desiderius may have first set eyes on a pointed arch. In 1065, the abbot made what

was essentially a shopping excursion to Amalfi, one of medieval Europe's busiest maritime gateways to the trading cities of

the Islamic world.

oday a picture-perfect Italian resort town,

Amalfi lies at the mouth of a deep ravine on the southern slopes of the Sorrento Peninsula, a lava flow of honey-colored

stucco houses and red-tiled roofs spilling down to the Bay of Salerno, around 70 kilometers (45 mi) southeast of Naples.

While Desiderius probably journeyed there by ship, I opted for a rental car to navigate the coastal road, a zigzagging,

cliff-side strip of tarmac overlooking the dangerously distracting beauty of the Tyrrhenian Sea.

oday a picture-perfect Italian resort town,

Amalfi lies at the mouth of a deep ravine on the southern slopes of the Sorrento Peninsula, a lava flow of honey-colored

stucco houses and red-tiled roofs spilling down to the Bay of Salerno, around 70 kilometers (45 mi) southeast of Naples.

While Desiderius probably journeyed there by ship, I opted for a rental car to navigate the coastal road, a zigzagging,

cliff-side strip of tarmac overlooking the dangerously distracting beauty of the Tyrrhenian Sea.

"[No city] is richer in silver, gold and textiles from all sorts of different places," wrote the poet William

of Apulia in the late 11th century, around the time of Desiderius's visit. "[M]any different things are brought here

from the royal city of Alexandria and from Antioch. Its people cross many seas. They know the Arabs, the Libyans, the

Sicilians and Africans. This people is famed throughout almost the whole world, as they export their merchandise and love

to carry back what they have bought."

Among Muslims, Amalfi's reputation was no less exceptional. In his Book of Routes and Kingdoms, the 10th-century

Turkish geographer Ibn Hawqal praised the city as "the most prosperous town in Lombardy, the most noble, the most

illustrious on account of its conditions, the most affluent and opulent."

This mutual admiration was rooted firmly in commerce. From as early as the ninth century, the tiny republic of Amalfi,

though nominally a Byzantine state, was in regular commercial and diplomatic contact with Muslim powers, including Abbasids,

Fatimids, Umayyads and more, from the Black Sea to the shores of the Iberian peninsula. The most important port in the

western Mediterranean, Amalfi was rivaled only by Venice as a conduit for the exchange of goods between East and West. With

chests full of tari—locally minted quarter-dinar coins inscribed in Arabic—and cargo ships bulging with

lumber, linen and local produce, Amalfitan merchants traded for oil, wax, spices and gold in the ports of Arab Sicily, North

Africa, Syria and Palestine. Trolling the bazaars of Constantinople, they bartered gold for jewels, perfumes, art objects

and precious textiles, such as purple silk, which had to be smuggled out of port, as it was illegal to export the imperial

cloth from Byzantium.

"The people of Amalfi were the first who, for the sake of gain, attempted to carry to the Orient foreign wares hitherto

unknown in the East," wrote the archbishop William of Tyre in the 12th century. "Because of the necessary articles

which they brought thither, they obtained very advantageous terms from the principal men of those lands and were permitted

to come there freely."

The eastern cities, from Baghdad to Cairo to Tunis, maintained thriving merchant colonies under local protection and, in

return, adopted a similarly accommodating, laissez-faire attitude toward its trading partners. When the Vatican led a campaign

in the ninth century to expel the Arabs from southern Italy, Amalfi refused to cooperate and even provided safe harbor for Arab

ships. Though it frustrated the Pope and alienated the stubborn republic from other Italian municipalities, the gambit paid

off: When Arab armies later besieged southern Italy, Amalfi was left untouched. Twelfth-century geographer and world traveler

Benjamin of Tudela stated: "The inhabitants of the place are merchants engaged in trade, who do not sow or reap, because

they dwell upon high hills and lofty crags, but buy everything for money, …and no one can go to war with them."

Except nature. In 1343, an underwater earthquake and tidal wave swept half of the city into the sea, and it never fully

recovered. Thus, what had once been the center of town, the Piazza Duomo (Cathedral Plaza), now abuts the harbor. Still,

the Piazza remains the city's main gathering place, with its tourist shops, gelato parlors and fountain. But the city's true

heart and soul, even overshadowing the Piazza, is the Cathedral of St. Andrew, restored in 1891 to its original 13th-century

Arab-Norman Romanesque glory. A riotous blend of Moorish stripes (ablaq, in Arabic, meaning "particolored"),

glittering mosaics and pointed arches, the façade is as clear a statement as you will find that Amalfi's imports from the

Islamic world amounted to more than silks and spices.

|

| Lower: vova pomortzeff / alamy |

|

Top: Though built in the mid-13th century, the interlacing pointed arches of the cloister at Amalfi's Basilica of the

Crucifix highlight the enduring appeal of Islamic designs in the port city. Above: A 17th-century fresco in the basilica's

crypt shows the building as Desiderius likely saw it in 1065—including the pointed arches that inspired his work

at Monte Cassino.

|

"[T]he artistic influences exerted by the Muslim world on southern Italy were a concrete part of [its] political and

economic history," wrote Islamic art historian and current New York Museum of Modern Art director Glenn Lowry in a 1983

monograph Islam and the Medieval West. "Consequently, …Islamic art played a major role in the formation

of southern Italy's vocabulary of forms. Its impact was both prolonged and profound."

It certainly had an impact on Desiderius as he ascended the towering steps of the cathedral then under construction. He

had come to Amalfi to shop for a gift for the future Holy Roman Emperor, Germany's King Henry iv,

in hopes of winning the young monarch's favor for Monte Cassino. Browsing the city's retail inventory of imported treasures,

Desiderius settled on some of the aforementioned contraband purple silks as an appropriate buttering-up gift for a rising

king, together with some silver vessels for the church. But according to Leo of Ostia, something else struck the abbot's

fancy as well: "Desiderius saw the bronze doors of the cathedral of Amalfi and as he liked them very much, he soon

sent the measures of the doors of the old church on Monte Cassino to Constantinople with the order to make those now

existing."

The doors that greet visitors to the cathedral today date to an earlier, ninth-century church, the Basilica of the Crucifix,

that stood adjacent to the one Desiderius saw being built. Unusually, the newer church was connected to the older one as an

expansive addition, resulting in a six-aisled cathedral with a forest of columns and arches that "rendered the sacred

building more similar to an Arabic mosque than to a Christian church," according to one church history. The basilica

still stands, though now separated from the main cathedral. During the 18th century, both were redecorated in the Baroque

style, but a restoration of the basilica in the mid-nineties revealed what art historians believe are the 10th- and

11th-century pointed arches along the nave. Above the arches, a double row of lancet windows framed with pointed arches

lines the upper gallery, where women worshiped. The accuracy of the restoration is confirmed by an early 17th-century mural

in the crypt that shows the basilica's interior prior to the Baroque makeover. This was the church that Desiderius would have

seen, and quite possibly the arches that might have inspired him, along with the bronze doors, to incorporate similar

features at Monte Cassino. Once more, Leo of Ostia provides evidence for this supposition by mentioning that, in addition

to builders from Constantinople, Desiderius hired Amalfitans as well as Lombards.

Ambling through the basilica, I took note of the pointed arches in the nave, as well as some smaller ones that are easy to

miss, tucked into the segmented sections, or squinches, of a semi-spherical "melon" dome above the stairs leading

down to the crypt. Dating to the time of the new church's construction, the dome's arches may have been "a conscious

allusion" to St. Andrew's Middle Eastern origins, Lowry speculated, and were "typical of North African and

Egyptian architecture.

"This can be seen in the mausolea of Aswan and Cairo," he continued, "as well as in more elaborate buildings

such as the Qubbat Barudiyan (ca. 1120) in Marrakesh. Indeed, the common association of squinches and melon domes with

funerary monuments in the Muslim world makes it reasonable for us to assume that both the forms and their context were

familiar to the many Amalfitans who had traveled and lived in the Middle East."

I let the startling significance of that statement sink in for a moment. What Lowry was suggesting was that the builders of

St. Andrew's Cathedral not only copied Islamic architectural features, but emulated their specific uses in religious settings

as well. This was more than imitation—it was wholesale adoption. That such spiritual and intellectual empathy existed

between Christians and Muslims during an era often overshadowed by the brute hostility of the Crusades is underscored by

a letter, cited by Lowry, written in 1076 from Pope Gregory vii to the Algerian amir An-Nasir

ibn Alnas. In brotherly tones, Gregory acknowledged their shared reverence for the prophet Abraham and recognized that "we

believe in and confess, albeit in a different way, the one God." Even more telling, Lowry noted, was that Gregory wrote

his letter in response to the amir's request to send a bishop to care for the local Christian population.

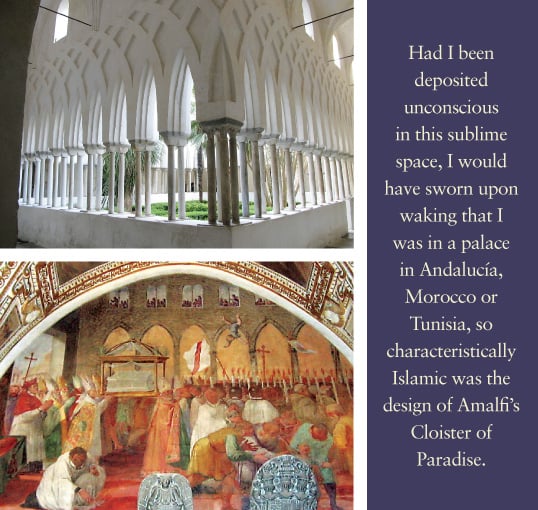

Leaving the basilica by a side door, I entered an adjacent courtyard, appropriately named the Cloister of Paradise. Had I

been deposited unconscious in this sublime space, I would have sworn, upon waking, that I was in a palace in Andalucía,

Morocco or Tunisia, so characteristically Islamic was its design. Built between 1266 and 1268 as a cemetery for Amalfi's

ruling merchant class, the courtyard features a central garden and palm trees enclosed by low walls supporting 120 slender,

white marble columns, arranged in pairs. Springing from the tops of the columns, in bas-relief, are so-called

"interlacing" pointed arches whose arcs intersect like rings of water from pebbles tossed into a pond.

Moving on from this tranquility to the jostle of Amalfi's tourist-choked streets at dusk, I noted further evidence of the

influence of Arab architecture. The narrow, white-washed, covered alleyways and winding passages reticulating the town strongly

resembled those of Tunisia's historic Sidi Bou Said, roughly 300 nautical miles to the southwest. So striking was the

similarity that you could fancifully imagine that one town simply broke off from the other, just as their respective continents

did some 500 million years ago.

Following the direction of all roads, I ended up at Amalfi's harbor. Though I could not see the lights of Africa twinkling

on the horizon, I could imagine them, together with the creaking, square-rigged merchant ships returning from her shores,

their holds redolent with spices, piled with chests of jewels and silks. Yet these ships also transported something more

lasting: ideas that changed the face of western architecture. Thus far, the trail of those ideas, specifically the pointed

arch, followed a clear geographical and chronological path northward from southern Italy to France. It was no less clear

that the pointed arch was a novelty unknown in the West until at least the 10th century, a device and a style inspired by

the architecture of the East, and perhaps, in some cases, even crafted by Muslim masons who had ended up in the West by war

or commercial contract.

By the time those masons were putting the finishing touches on the arches of Amalfi's basilica, a graceful arcade of similar

arches had been a familiar feature of another house of prayer for nearly a century: the Great Mosque of Mahdia, along Tunisia's

Sahel coast, where the trail would lead me next.

|

dagger held in the fist" was how

Ibn Khaldun, the 15th-century Tunisian-born historian, once described the strategic peninsula of Mahdia, which juts into

the Mediterranean about 250 kilometers (150 mi) south of Tunis. Indeed, the tip of the dagger's blade points east, straight

at one of the region's most perennially coveted prizes: Egypt. In the early 10th century, the man wielding more than

metaphorical daggers was 'Ubaidallah, founder of the Fatimid dynasty. This rogue general assumed leadership of Tunisia by

ousting the Aghlabids, the Muslim rulers of North Africa and Sicily for the past century and the nominal representatives of

the Abbasid caliph in far-off Baghdad. More concerned with trade than military matters, the Aghlabids proved no match for

'Ubaidallah's army and ambition. A capable, albeit ruthless, ruler—he assassinated those who helped him to power, and

theologians and lawyers with whom he disagreed were publically flogged—'Ubaidallah styled himself the mahdi

("chosen one"), the redeemer of Islam. That this was heresy did not deter him, and the city he built on the

strategic peninsula he dubbed Mahdia in reference to his self-anointed title.

dagger held in the fist" was how

Ibn Khaldun, the 15th-century Tunisian-born historian, once described the strategic peninsula of Mahdia, which juts into

the Mediterranean about 250 kilometers (150 mi) south of Tunis. Indeed, the tip of the dagger's blade points east, straight

at one of the region's most perennially coveted prizes: Egypt. In the early 10th century, the man wielding more than

metaphorical daggers was 'Ubaidallah, founder of the Fatimid dynasty. This rogue general assumed leadership of Tunisia by

ousting the Aghlabids, the Muslim rulers of North Africa and Sicily for the past century and the nominal representatives of

the Abbasid caliph in far-off Baghdad. More concerned with trade than military matters, the Aghlabids proved no match for

'Ubaidallah's army and ambition. A capable, albeit ruthless, ruler—he assassinated those who helped him to power, and

theologians and lawyers with whom he disagreed were publically flogged—'Ubaidallah styled himself the mahdi

("chosen one"), the redeemer of Islam. That this was heresy did not deter him, and the city he built on the

strategic peninsula he dubbed Mahdia in reference to his self-anointed title.

|

|

Above: The Great Mosque of Mahdia, Tunisia, built in 916, was likely known to Amalfitan merchants. Its builders, in turn,

would have known well the Great Mosque of Kairouan, below, where arches date from the early to mid-ninth century.

|

|

In 916, 'Ubaidallah ordered the construction of Mahdia's Great Mosque on the narrow isthmus connecting the peninsula to

the mainland. Much of the original mosque has been destroyed, rebuilt and/or restored on several occasions, with the

critical exceptions of the sections I had come to see: the main entryway and arcade.

Stepping through the entryway once reserved only for the ruler and his entourage, I crossed into an aisle of pointed arches

surmounted by groin-vaulting formed by the joined tips of quadrilaterally opposing pointed arches. The structure looked as

if it could have come from any Gothic church in Europe—but it had been built at least a century before the style was

ever dreamt of there. Was it possible that some mason who shaped the golden limestone blocks supporting these arches later

also traveled to Amalfi? Could some Muslim merchant, telling tales of home or bragging of the beauty of his city's houses

of worship, have described this very place to an intrigued European audience? Or perhaps it was an Amalfitan merchant who

passed this way, possibly along this very arcade, who shared the news back home that the buildings across the water were

more stunning than anything he had seen at home. The lack of documentary evidence makes it impossible to say, yet the fact

remains that by the early 10th century, here in this Arab port routinely known to Amalfitan merchants, the pointed arch was

established and prominent.

As I stood there, mentally transported back to that distant century, a bent and sun-bronzed elderly man jolted me back to

this one. Ibrahim Nouri, the mosque's custodian, was pleased to know I had an interest in the building's history, and pointed

out to me the literal joint in time where the original mosque ended and the restored one began.

"This kind of building could not be created again," he said with matter-of-fact reverence. The reason, he assured

me, was that "it was built by faith," implying that there may have been more to the use of the arch than simple mechanics.

The faith Nouri spoke of inspired the creation of what remains North Africa's holiest city, some 130 kilometers (80 mi)

inland: Kairouan.

ounded in 670 by the Arab general Oqba

ibn Nafi on his march across North Africa, this desert city, whose name literally means "halting place," was laid

out as a military camp with two structures at its center: a mosque and the commander's residence. Though nothing survives of

Oqba's mosque, the current Great Mosque of Kairouan was built in the early to mid-ninth century, which makes it one of the

oldest Muslim houses of worship in the world as well as the model for all subsequent North African mosques.

ounded in 670 by the Arab general Oqba

ibn Nafi on his march across North Africa, this desert city, whose name literally means "halting place," was laid

out as a military camp with two structures at its center: a mosque and the commander's residence. Though nothing survives of

Oqba's mosque, the current Great Mosque of Kairouan was built in the early to mid-ninth century, which makes it one of the

oldest Muslim houses of worship in the world as well as the model for all subsequent North African mosques.

Surrounded on three sides by the crenellated walls of Kairouan's historic old city, the mosque resembles a fortification

from the outside, with high walls and a tapering, quadrangular minaret that is believed to date to 730—a century or

so earlier than the rest of the mosque and perhaps the world's oldest standing minaret. The western entryway, encased within

an enormous buttress, provided but temporary shade between the sun-baked old city and the mosque's sun-drenched open courtyard,

or sahn, enclosed by a double-bayed arcade. Three sides of the arcade feature the slightly pointed, horseshoe arches

common to the Islamic architecture of Morocco and southern Spain. But the southern portico, fronting the prayer hall, differs

both chronologically and esthetically. Built about 40 years before the rest of the mosque, in 836, its acutely pointed arches

flank both ends and the entryway of the prayer hall. I learned why the architects chose this particular application of pointed

arches from modern architect Mohammad el Hedi Belahmar of Tunisia's National Heritage Institute who, as luck would have it,

happened to be at the mosque that day conducting surveys.

"The idea was to focus attention on the entrance to the prayer hall, to make a statement that the entry porch was

important," Belahmar told me. It also provided visual balance, he said, with eight rounded bays anchored on either end

by pointed arches solving the problem of how to even out the space. The use of the pointed arch in North Africa was fairly

new at the time this mosque was built, Belahmar said, and the arches' distinctive shape suggested to him a Persian influence

or origin that, over time, was Arabized in form and name.

"In French they are called arc brisé, and in Arabic, kaous munkassar, which both mean 'broken

arch,'" he said. As for their appeal to early Muslim builders, Belahmar saw it as "basically an engineering solution,

to provide greater strength to buildings."

Later that evening, I heard a different opinion from another architectural authority, Lotfi Abd Eljaoued, director of Kairouan's

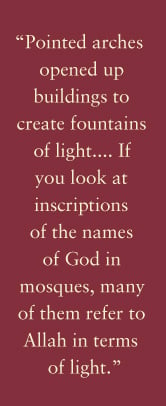

Museum of Islamic Arts. "Essentially, pointed arches opened up buildings to create fountains of light," Eljaoued told

me, as we sat poolside in the lantern-lit twilight at Kairouan's La Kasbah Hotel, a restored fortress in the heart of the medina.

"Light was important. If you look at inscriptions of the names of God in mosques, many of them refer to Him in terms of light."

|

Surah 24 of the Qur'an, Al-Noor ("Light") is one example, while, according to Muslim tradition, one who

recites the name of God Al-'Aleem ("The All-Knowing") will literally become "enlightened" with

divine understanding. Such interpretations of the concept of light sounded much like those of Abbot Suger, and they started

me thinking that there may have been more going on all along in the use of the pointed arch than simple mechanics. Still,

Muslim masons never used the pointed arch to reach the dramatic heights of Gothic cathedrals. While the one may have inspired

the other, the reason for this distinction was, literally, fundamental.

"From early on, Christian church architecture was identified with the basilica, which is a long and tall building type,

whereas Islamic architecture saw its beginnings in the courtyard house structure, which is low, broad and encompassing,"

according to medieval Islamic art specialist Yasser Tabbaa, visiting professor of art history at nyu-Abu Dhabi.

"Some later mosques, whether Ottoman or Persian, did aspire to height—the former by domes, the latter by iwans

[high-vaulted, three-sided entrance spaces], for example—but none required stabilization by the use of flying buttresses."

In 969, inspired not so much by light as the desire for land and wealth, the Fatimids wrested from the hands of its Abbasid

governors the land at the end of the Mahdia peninsula's dagger point: Egypt. One of those governors had been the man

responsible for the next monument on the trail of the arch: the eponymous Mosque of Ibn Tulun, in the city the Fatimids

renamed Cairo.

orn in 835 as the son of a Baghdad slave,

Ibn Tulun rose through the ranks of the Abbasid military to a position of power in Samarra, Iraq, then a flourishing center

of art and architecture under the caliph al Mu'tasim. Assigned in 868 to serve as regent of Fustat, then the Egyptian capital,

Ibn Tulun expanded and enriched the city with public-works projects, including a hospital and an aqueduct. Ambitious as well

as civic-minded, he declared independence from Baghdad within two years of his appointment and established his own dynasty,

the Tulunids. A new regime required a new capital, and so Ibn Tulun transformed an area northeast of Fustat into a spectacular

government center called al-Qata'i (meaning "the wards" or "the quarters"), with a palace complex, gardens

and a maydan (public square) vast enough for him and his court to play polo. At the center was Ibn Tulun's crowning

achievement: a mosque complex of unprecedented size (2.5 hectares/6.5 acres). The design of Ibn Tulun's city complex and

mosque reflected the ruler's Samarran heritage and taste. Built of red brick faced with stucco, the mosque features intricate

decorative plasterwork in vegetal motifs and a minaret with a spiral, exterior staircase reminiscent of Samarra's famous

Malwiya ("snail shell") minaret. High double walls surround the mosque, creating a serene and peaceful environment

inside. In the area between the walls, called a ziyada, teachers gathered to discuss the Qur'an, theology, astrology,

medicine and more. When discussions and throats ran dry on hot summer days, a fountain in the courtyard dispensed cool

lemonade. A near-continuous strip of Qur'anic verses can still be seen along the interior walls, carved into wooden beams

salvaged, legend has it, from the wreckage of Noah's Ark.

orn in 835 as the son of a Baghdad slave,

Ibn Tulun rose through the ranks of the Abbasid military to a position of power in Samarra, Iraq, then a flourishing center

of art and architecture under the caliph al Mu'tasim. Assigned in 868 to serve as regent of Fustat, then the Egyptian capital,

Ibn Tulun expanded and enriched the city with public-works projects, including a hospital and an aqueduct. Ambitious as well

as civic-minded, he declared independence from Baghdad within two years of his appointment and established his own dynasty,

the Tulunids. A new regime required a new capital, and so Ibn Tulun transformed an area northeast of Fustat into a spectacular

government center called al-Qata'i (meaning "the wards" or "the quarters"), with a palace complex, gardens

and a maydan (public square) vast enough for him and his court to play polo. At the center was Ibn Tulun's crowning

achievement: a mosque complex of unprecedented size (2.5 hectares/6.5 acres). The design of Ibn Tulun's city complex and

mosque reflected the ruler's Samarran heritage and taste. Built of red brick faced with stucco, the mosque features intricate

decorative plasterwork in vegetal motifs and a minaret with a spiral, exterior staircase reminiscent of Samarra's famous

Malwiya ("snail shell") minaret. High double walls surround the mosque, creating a serene and peaceful environment

inside. In the area between the walls, called a ziyada, teachers gathered to discuss the Qur'an, theology, astrology,

medicine and more. When discussions and throats ran dry on hot summer days, a fountain in the courtyard dispensed cool

lemonade. A near-continuous strip of Qur'anic verses can still be seen along the interior walls, carved into wooden beams

salvaged, legend has it, from the wreckage of Noah's Ark.

|

|

In the mosque of Ibn Tulun, built in the later ninth century, pointed arches rise from brick piers similar to those commonly

used in Ibn Tulun's native Samarra, Iraq.

|

Providing shape and grandeur to the overall structure, however, are dozens of brick piers supporting the prayer hall and

enclosing the courtyard, topped by row upon row of elegant, pointed arches. Stories associated with the construction of the

mosque link these features to yet more Islamic-Christian cooperation. According to the 10th-century Egyptian historian al-Balawi,

when Ibn Tulun learned that his new mosque would require 300 columns that could only be obtained by gutting local churches, the

ruler "thought this wrong, and would not do so." Hearing of this, a Coptic Christian prisoner, who happened to be an

architect, offered to design the mosque without stone or marble columns, opting for brick piers instead. Ibn Tulun was "so

pleased that he set him free and entrusted him with the work."

While Coptic Christians may have been involved in the construction, the design of the mosque, most art historians agree, is

decidedly Islamic, and specifically Samarran, whose style favors brick piers. Whether the mosque's pointed arches were

likewise patterned after earlier Syrio-Iraqi examples—such as those mentioned to me by Northedge—is a question I

put to Bernard O'Kane, professor of Islamic art and architecture at the American University in Cairo, as we strolled through

the mosque in our stocking feet. A trim, bespectacled man whose Irish brogue remains unwithered after 30 years in the city, O'Kane

echoed Northedge's precautions against definitive answers to what inspired the use of the pointed arch among Muslim architects. He

did acknowledge, however, that the objective of filling structures with symbolic light, as Eljaoued had conjectured, was a tempting

explanation.

"The Fatimids, for instance, named their mosques after epithets of light," O'Kane pointed out, rattling off several

local examples. "Al-Anwar was the original name of the mosque of al-Hakim, meaning 'shining with splendor.' Al-Azhar means

the same thing. Al-Aqmar means 'the moonlit mosque.' In their choice of Qur'anic verses in the mosque, they also frequently

picked those that were related to light. So the concept of enlightenment, or giving light, is important."

Despite its inspiring interior and historical importance, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun actually takes a chronological backseat to a

far less conspicuous, subterranean bit of engineering nearby, on Roda Island in the middle of the Nile: the Nilometer.

|

|

The sluice-gates of the Nilometer, built 108 years before the founding of Cairo, are the earliest known pointed arches in Egypt.

|

Built in 861, the Nilometer measured the height of the annual Nile flood—an important function that foretold whether the

coming year would bring feast or famine. The structure is simple: a 13-meter (40') stone-sheathed hole in the ground with a

graduated column in the center for measuring the depth of the water. But halfway down the pit, there is a set of wall recesses

vaulted with Egypt's oldest surviving pointed arches.

"Careful measurements show that the pointed arches of these recesses have been struck from two centres one-third of the

span apart," observed Creswell, in his characteristically clinical style. "That is to say these arches are what the

Gothic architects called 'tiers-point', but they are three centuries earlier than any Gothic example."

Now blocked up, the niches once served as sluices for the Nile's floodwaters. The arches don't appear to serve any critical

structural function and were thus probably decorative. It is possible that the Nilometer's designer, Persian astronomer

Abu'l 'Abbas Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathir al-Farghani, simply incorporated the arches as a contemporary architectural

feature. Whatever the motive, it makes clear that by the mid-ninth century, the pointed arch had, in effect, gone viral

across Egypt and the Maghreb, and would be on its way to southern Italy within a century or so after that. But this trend

began further east, back along the path of Islam as it spread west from the Arabian Peninsula. A major crossroads on that

journey was Islam's third holiest city after Makkah and Madinah—Jerusalem.

he Dome of the Rock, with its shining

gold-sheathed roof and azure tiles, is one of the world's most recognizable buildings. Indeed, it's an architectural

synecdoche not only of Jerusalem, but of the entire Middle East. Together with the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque, it comprises

al-Haram al-Sharif, "The Noble Sanctuary," from which Muslims believe the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven

during his miraculous "Night Journey." A shrine, not a mosque, the structure surrounds the massive rock where

Muhammad was taken up, where Jesus taught and where the temples of Solomon and Herod once stood.

he Dome of the Rock, with its shining

gold-sheathed roof and azure tiles, is one of the world's most recognizable buildings. Indeed, it's an architectural

synecdoche not only of Jerusalem, but of the entire Middle East. Together with the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque, it comprises

al-Haram al-Sharif, "The Noble Sanctuary," from which Muslims believe the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven

during his miraculous "Night Journey." A shrine, not a mosque, the structure surrounds the massive rock where

Muhammad was taken up, where Jesus taught and where the temples of Solomon and Herod once stood.

|

|

lars r. jones / aga khan visual archive, mit

|

|

The points of the arches on the inner colonnade of Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock, built between 688 and 691, are

subtle, but they both solved an architectural problem and helped begin to distinguish Islamic from Byzantine

Christian styles.

|

Though both its interior and exterior have been embellished and restored throughout the centuries, the Dome of the

Rock's octagonal framework, with two concentric rings of arched colonnades encircling the rock, remains the same as

that decreed by Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik, who had it built between 688 and 691. It is the world's oldest Islamic

building, and inside it are what some say are the oldest pointed arches in Islamic architecture.

Yusuf Natsheh, in charge of archeology at the shrine, granted me permission to visit the structure in the company of

Ahmad Taha, director of Al-Aqsa's Islamic Museum. The building is noted for its mathematical perfection: Each outer

wall, for example, is as long as the dome is wide and as high from the base: 20 meters (67' feet). The sumptuous

interior is awash in glittering mosaics, marble paneling and painted woodwork, while the arches of the inner colonnade,

those supporting the dome, are striped by alternating light and dark stone (ablaq, as in Córdoba's Great Mosque and

the façade of Amalfi's cathedral), and they are, ever so slightly, pointed. The overall impression is actually that

of some gloriously gilded Byzantine interior. Taha explained why.

"The Umayyads imported Christians as workers and administrators," he said. "So there are many

Byzantine elements, because the artists and workers who made the mosaics were Byzantine, Syrian Christians."

Were these same workers responsible for the Dome of the Rock's pointed arches? Possibly. The pointed arch is not a

common feature of Byzantine architecture, but it does have Syrian precedents, as Creswell wrote and Northedge suggested.

But why its use in this particular time and place, I wondered? Throughout my journey, I had been hearing both

practical and philosophical motives for the arch's development. It was here that the two merged.

On the purely functional level, the pointed arches were a solution to a technical problem. In any circular colonnade,

the arch openings on the exterior face are larger than those on the interior face because the radius of one is larger

than the other by the thickness of the wall. This means that the underside surfaces of the arches (the intrados)

tilt inward, rendering them visually unbalanced. Builders of the Dome of the Rock corrected this problem by pointing

the interior sides of the arches to raise the intrados to a uniformly horizontal level. (Builders averted this problem

in the outer colonnade by making it octagonal. Today, the arches of both sides of the inner colonnade are pointed,

owing to a later restoration.)

Yet there may have been a deeper motivation. The Dome of the Rock, art historians generally agree, was a declaration

of Islam's triumph over (or, to Muslims, fulfillment of) both Judaism and Christianity. This was made clear by virtue

of its location and design. Modeled after Byzantine churches in general and the nearby Church of the Holy Sepulcher

in particular, the Dome of the Rock was intended to outclass them all while defining the new faith. A prominent

inscription featuring verses from the Qur'an (4:171) directly underscores the theological distinctions between Islam

and Christianity: "For God is One God: Glory be to Him: Far exalted is He above having a son." In the midst

of these bold ornamental pronouncements, how did a simple upward nudge in an arch make a statement?

"[G]iven the seminal position of this building in the early history of Islamic architecture, we need to consider

the possible role of the adoption of the pointed arch in starting to establish, in architectural terms, a cultural

identity for the new religion," wrote architectural historian Peter Draper, author of The Formation of

English Gothic.

Was this the "deliberate esthetic" Northedge spoke of at the beginning of my journey? Perhaps. Still,

the conventional view is that the Dome of the Rock's pointed arches date from a later time or, if they are original,

were simply "on-the-ground corrections," with no loftier significance, as

nyu-Abu Dhabi's Tabbaa characterized them. Either way, they would ultimately become

"a distinguishing feature" of Islamic architecture, according to Draper: a trend that may have begun here

in Jerusalem, in the far-flung fortresses and hunting lodges of Umayyad princes in Jordan's eastern desert as

Northedge suggested, or in a less conspicuous locale, roughly 30 miles northwest and about 10 meters (30') underground.

o it was that I ended up paddling

around the translucent, sun-dappled waters of the Cistern of Ramla in a fiberglass dinghy. The boat's beamy cockpit

offered the best vantage points for close-up views of the arches, erected here—so says a Kufic inscription on

one wall—"with God's blessings" and at the command of Caliph Harun al-Rashid, "in the month of

Hajj, in the year One Hundred and Seventy Two" (May 789 ce). As such, the cistern

is not only a uniquely remaining Abbasid monument, but "constitutes the earliest known example of the systematic

and exclusive employment of the free-standing pointed arch," according to Creswell's own emphasis. Graceful and

perfect, the arches spring from the surface of the water in a series of bays, forming six symmetrical aisles, as if in

some flooded and long-forgotten Gothic church. Such a pity, I thought: All that work for something rarely seen even in

its own day, considering that most visitors to the cistern came merely to fill their water buckets from above rather

than admire the engineering work of art below.

o it was that I ended up paddling

around the translucent, sun-dappled waters of the Cistern of Ramla in a fiberglass dinghy. The boat's beamy cockpit

offered the best vantage points for close-up views of the arches, erected here—so says a Kufic inscription on

one wall—"with God's blessings" and at the command of Caliph Harun al-Rashid, "in the month of

Hajj, in the year One Hundred and Seventy Two" (May 789 ce). As such, the cistern

is not only a uniquely remaining Abbasid monument, but "constitutes the earliest known example of the systematic

and exclusive employment of the free-standing pointed arch," according to Creswell's own emphasis. Graceful and

perfect, the arches spring from the surface of the water in a series of bays, forming six symmetrical aisles, as if in

some flooded and long-forgotten Gothic church. Such a pity, I thought: All that work for something rarely seen even in

its own day, considering that most visitors to the cistern came merely to fill their water buckets from above rather

than admire the engineering work of art below.

Yet Ramla represented "a new type of language of architecture," as Draper put it. While earlier, scattered

examples throughout the Middle East may have been the first utterances of this new language, the pointed arches at

Ramla represented its first fully formed sentences. This language would grow and spread over the ensuing centuries,

culminating in the epic architectural poetry of medieval Europe's Gothic cathedrals.

In my quest to establish a chronology for the pointed arch, I discovered that while the physical feature can be traced

from place to place, as an idea its route remains more difficult to pin down. This was because during the Middle Ages,

as Lowry wrote, "the intensity of the contacts between the [West] and the Muslim world were not static, but

dynamic, changing from one mode of artistic influence to the next."

And just as the Christian West had adopted the pointed arch from the Islamic East, so too did Islam acquire cultural

vocabulary from Persia, Byzantium, India, Asia, Africa and even Europe. With this in mind, Natsheh summarized the

history of Islamic art for me by paraphrasing his former professor (and Creswell's contemporary academic rival), the

late Ahmad Fikri.

"Students of Islamic art think of Islamic art as a smart and beautiful child," he said with a smile. "

But this child's eyes are from Rome, his hands are from Persia, his legs are from Coptic Egypt. And so all of these

elements mixed together, to come up with a good, smart boy."

If so, one of the most profound movements in the history of art—the Gothic—owes its genes to this clever child.

For Futher Reading: Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Arab Region. Friedrich Ragette. 2003, Axel Menges, 978-3-932565-30-4, $70 hb.

|

Freelance writer Tom Verde (writah@gmail.com), a frequent

contributor to Saudi Aramco World, holds a master's degree in Islamic studies and Christian-Muslim relations.

He dedicates this story to the memory of his teacher, advisor, mentor and friend, the late Ibraham Abu-Rabi, with

whom he has shared many journeys. |