|

|

|

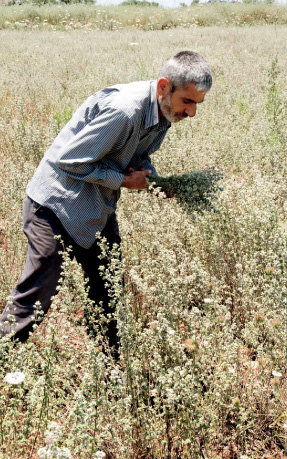

"One kilo of seeds produces 5.5 million plants," explains Abu Kassem, above, as he gathers

samples of the herb za'tar, or wild thyme, from one of his southern Lebanon fields,

which he harvests by hand with a scythe. Right: Stripping za'tar off the sprigs.

|

"My suitcase isn't overweight!" explained the Jordanian woman in front of me to the check-in agent at the

airport in Amman. To make her point, she pulled from it a large plastic bag of dried, crushed leaves. "This is not

'extra weight'! It's za'tar I'm taking back for my relatives."

|

|

|

Above, lower: Crushed and sifted, za'tar leaves, right, are ready to be mixed with sesame seeds (left) and uncrushed

sumac berries (top).

|

Though the clerk still charged her for excess baggage, he expressed his sympathy, understanding—like so many

Arabs—that za'tar is not an extra but an essential. Even so, the woman was far calmer than the Australian-Lebanese

man who made the local news when Brisbane customs officials confiscated his mother-in-law's za'tar baggies. He called it a

"tragedy" and a "disaster," and demanded to speak to a member of parliament. Indeed, it is neither

hummus nor falafel that Arabs pack away in their suitcases to bring along the flavor of home: It is za'tar. And

they do so with passion.

The Arabic word za'tar (zaah-tar) means two things: It is the name of a herb that grows primarily

in the hills of the eastern Mediterranean and, more importantly, it is the name of a mixture of that herb blended with sesame

seeds and other spices—a blend made by mixing nostalgia with necessity. Eaten as a dip with olive oil, za'tar is a ubiquitous

staple on breakfast tables in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and Palestine. "We had nothing to eat but za'tar and olive oil"

is an expression meaning, "We had only our staples." Today, za'tar is also loaded with symbolism and identity, appearing

in art and music, such as poet Mahmoud Darwish and composer Marcel Khalife's collaboration "Ahmed Al Arabi," in which za'tar

stands for inner strength and home. The mixture is also finding its way into hip restaurants that draw people with the comfort implied

by the word, such as the Za'tar wa Zeit chain, which began in Lebanon and has expanded to several other Arab countries.

There is unfortunately no direct translation for za'tar in English, although it is often called wild thyme. "It is a

taste more than a species," explains Jihad Noun, an expert on medicinal and aromatic Lebanese plant species. He becomes

animated when the subject turns to za'tar.

"There are 22 herb species referred to as za'tar in the region. It is the essential oils they have in common. They all come

from the same Lamiaceae, or mint, family, which includes savory, oregano and thyme. Personally, I can eat za'tar anytime.

Za'tar is what opens our palates."

|

|

With multiple varieties of wild thyme and an infinite number of combinations of za'tar's ingredients

available, Abu Kassem prepares his own favorite mix. |

Za'tar mixtures vary by region and even from shop to shop and home to home. Nearly everyone has an opinion about where to find the

best mix—and it usually happens to be in his or her own hometown.

|

|

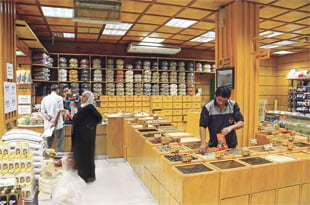

Leading spice shops such as Amman's Izhiman, can offer a dozen or more varieties. "We sell five tons

of za'tar a month, says executive manager Naser Matouq."

|

The biggest national producer and exporter of za'tar is Jordan. In Suweifeh, a lively middle-class shopping district of Amman, Izhiman

and Kabatilo are two shops that anchor a street notorious for its traffic jams. While Izhiman started out in Jerusalem in 1893

specializing in coffee and Kabatilo specialized in spices, they are both equally renowned today for their za'tars. Kabatilo offers 12

different kinds, with the four premier mixes taking the prime spot near the cash register. Such premium za'tar comes to Jordan from the

hillsides of the West Bank, where growers from around the villages of Jenin, Qaliqiya and Tulkarem collect wild za'tar in the late spring.

The other za'tars in Jordan come from cultivated fields.

"Wild mountain za'tar is very spicy, usually too strong on its own, but cultivated za'tar in Jordan is grown on flat land, and is

cheaper and less tasty," explains Naser Matouq, executive manager and the fourth generation of his family to work at Izhiman.

That shop offers seven za'tar mixes, all made from Palestinian or Jordanian za'tar and all lined up in open wooden bins where the

"za'tar manager" helps customers sample and choose. He will, upon request, add sumac, sesame seeds or salt to fine-tune one

of the mixtures to a discerning customer's preferences before sealing up the plastic bags. The original mix is called Za'tar Royal:

za'tar, sumac and sesame seeds, all in measured proportions. A less expensive option adds smoked wheat to make the za'tar last longer.

But the greatest demand is for Za'tar Special, which includes za'tar, sumac, sesame, roasted wheat, coriander, caraway, fennel seeds,

dill and salt.

|

|

|

Top: Flatbreads with a paste of za'tar and oil

become mana'esh, "the ultimate za'tar comfort food," prepared above at Izhiman, where the baker's output

immediately finds eager consumers, above. |

"In Jordan alone, we sell five tons of za'tar a month," says Matouq. "It's so much a part of who we are. All our mothers

used to make us eat za'tar sandwiches before exams because everyone believes za'tar makes you smarter."

Just outside Amman, Izhiman's production facility dedicates two entire floors to za'tar production. White cloth sacks of dried West Bank

za'tar leaves fill up a room of shelves—away from sunlight, which can degrade the za'tar's natural oils. Workers hand-sift the

za'tar three or four times in small quantities to remove stems or debris; they then put the herb through a special machine to crush it.

Za'tar is almost always mixed with sumac, a berry grown in the region, which undergoes a similar process, turning a vibrant maroon as its

shell and seed are separated. The spice—not the same as North America's poison sumac—adds a tart, lemony flavor to the mix.

"Forty-seven percent of the sumac berry is lost, as we only use the outside, not the seed," says Matouq. "But it's worth

it. Cheap za'tar is mixed with citric acid instead, but that is not acceptable to me, taste-wise or visually.

"Sesame seeds were once not part of the mix, but it is now rare to leave them out," he adds. "We use local sesame seeds

for all the za'tar mixes except those intended for mana'esh. For our mana'esh mix, we use Ethiopian or Sudanese seeds, which

are smaller but less likely to burn."

Mana'esh is the ultimate za'tar comfort food: a circular flatbread spread with a paste of za'tar and olive oil, best served piping

hot from a wood-burning oven. There may be no greater mana'esh experience than stopping in the little mountain villages that dot the

spine of Lebanon, where you will come across family bakeries that make your mana'esh on the spot, using either their own za'tar mix or,

if you prefer, the one you've remembered to bring from home. Some like the dough crispy and paper thin; others prefer it thick and soft.

|

|

With the help of longtime experts such as Abu Kassem, below, Barbara Abdeni Massaad of Beirut

surveyed this "icon to the Lebanese, a way of life" nationwide, from rustic mana'esh on a paddle

near a wood-fired oven in Nabatiyah, left, to urbane culinary geometry at the trendy Za'tar wa Zeit

(Za'tar and Olive Oil) restaurant in Beirut, right. |

"We make ours thick so that it holds more of the mixture," says baker Nabil Kamal Eldin in the town of Batloun. His daughter

Sara rolls out the dough and tops it with oil and za'tar, while he mans the wood-burning oven. The za'tar turns brownish-black as it

bakes, and the cooking turns the flavor mellow, salty, lemony, piquant.

"The man'oushé is an icon to the Lebanese, a way of life," says Barbara Abdeni Massaad, using the Lebanese

singular of mana'esh. "When someone comes back to Lebanon, they want to eat a man'oushé." In 2005 Massaad

published Man'oushé: Inside the Street Corner Lebanese Bakery, containing some 70 recipes and photographs. Born in

Lebanon, she spent several years in Florida as a teenager, working at her father's Middle Eastern restaurant. After returning to Lebanon,

where she married and had three kids, she decided to combine her passions for food and photography to produce a book. "My favorite

food was pizza," she recalls, "so I thought I would do research on pizza. Then I woke one night and thought of the 'Lebanese

pizza,' the man'oushé. Why am I thinking about Italy, when right here we have the man'oushé? I began visiting as many of

Lebanon's bakeries as I could—and that's around 250 bakeries."

Along the way, she discovered some unique mana'esh, including ones that include Aleppo pepper paste or ground walnuts in the spice

mixture. But Massaad also believes in the experience of making mana'esh at home with her kids. She's learned a few tips for home baking

from the professional bakers. "The key to a good man'oushé is having the right za'tar mix and baking at a high temperature.

You don't want the best za'tar for man'oushé. The highest grade of za'tar can become quite bitter when cooked. Bakers also save

money by mixing the spices with vegetable oil, rather than just olive oil. There is actually a lightness that comes with that, even

though olive oil is still precious."

Since writing Man'oushé, Massaad has landed her own television show, "Helwi Beirut" ("Sweet Beirut"),

and become a fixture of the Lebanese slow food movement. Exploring Lebanon's food culture with her camera and her four-wheel-drive

led her to Zawtar, a southern Lebanon village with lush green fields as far as the eye can see. It is home to Mohammed Ali Naami, a

farmer better known as Abu Kassem. He used to make his living collecting za'tar from the mountains overlooking the Litani River.

Today he only goes to those mountains for the peace the sound of the river brings him.

Eating a breakfast of beans, olives and za'tar with his family at a table just outside his house, he overlooks some of the two hectares

(5 acres) of za'tar fields he now cultivates, planted from wild za'tar seeds. The son of a tobacco farmer, he had to quit school when

he was 13, but today Abu Kassem is one of the success stories of a United Nations program to revive south Lebanon's economy after the

Israeli withdrawal in 2000.

"One kilo of seeds produces 5.5 million plants," Abu Kassem explains as he walks you through the za'tar, which bursts with

aroma when a leaf is torn. "In the wild, I could only collect za'tar once a year, but now I can have four or five crops a year.

I'd never been anywhere before, but now I've been to Italy and Jordan and even Libya to talk about growing za'tar as good as the wild

stuff. Za'tar has given me and my family everything."

Much of south Lebanon "was an area very dependent on tobacco farming, which is not particularly good for the soil, expensive to

grow, and dangerous for the women and children who often help process the leaves," says Carol Chouchani Cherfane. She works in

Beirut for the un's Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, which did the study on the south. "We realized za'tar was

a feasible crop, especially as it goes with sumac, which was another viable crop for the region. And za'tar is resilient."

Jihad Noun also worked on the project. "It isn't sustainable, for the farmer or the crop, to depend on the wild crop,"

he explains. "There is a growing market for za'tar, and the wild cannot support it alone without damaging the natural habitat.

When the farmers use the seeds, they create the same taste without damage."

Noun is also working to standardize za'tar mixtures in Lebanon, as it is a cash crop for import and export. "So many factors

affect the flavor of za'tar. In Jordan, for example, za'tar is cut earlier than in Lebanon—spring as opposed to summer—because

of drier conditions, and that changes the flavor and color. How much salt is allowed in the mix, what are permissible additives, what

is the percentage of sesame seed and sumac—these are all issues. There are laws for standardization in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan,

but there is no entity effectively measuring compliance."

Abu Kassem—along with generations of grandmothers and other farmers—quickly tells visitors that za'tar isn't just

food—it's medicine. He believes it can cure grippe, eczema, period cramps, colds, nerves, stomachaches and much more.

History—mixed with tradition—is there to back him up. "In medieval texts of the region, za'tar was believed to cure

indigestion, flatulence, congestion and bad breath," says Juan E. Campo who, with his wife, Magda, teaches Middle Eastern food

history at the University of California-Santa Barbara. "In fact, products like Listerine today include thymol, which is a

derivative of the same type of plant. In an ancient Assyrian text, its smell is purported to revive an epileptic."

Za'tar's power is noted in the Bible as well: "Psalm 51, verse 7, says, 'Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean; wash me,

and I shall be whiter than snow,'" Noun explains. "Hyssop was the ancient word for za'tar," he says, adding that it

is often still used in church services in Lebanon.

Za'tar also has many culinary incarnations. Certain varieties are pickled in vinegar and others often eaten fresh with slices

of cheese, though they can never compete with the portability and longevity of the dried mix. Za'tar has traveled with guest

workers from the Levant to other Arab countries, particularly those of the Arabian Peninsula, where bakeries manned by young

Lebanese, Syrian and Palestinian men now produce mana'esh as good as any in their native lands. "I get mail from all over

the world with people's personal stories about za'tar," says Barbara Massaad, the Man'oushé author. "Bakeries

in Polynesia, Australia and France have told me they are making mana'esh these days because of the popularity it's developed, thanks

to immigrants from here."

|

In large, ethnically Arab communities in the us, za'tar is widely available in neighborhood Middle

Eastern grocery stores. But you wouldn't think to find it in the Great Plains in the central us—lands

settled by immigrant Norwegians and Germans, where brutal winters are a sharp contrast to the hot, sunny weather za'tar needs to

thrive. Yet if you walk into Sanaa's, a restaurant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, you'll find that mana'esh is at the heart of the

popular Saturday lunch buffet. In the line in front of you might be people from two distinct groups of local Arab-Americans and even

more of the descendants of those Germans and Norwegians.

|

|

Jay Pickthorn |

|

Sanaa Abourezk first lured customers to her now-popular Sioux Falls, South Dakota eatery by sprinkling

olive oil and za'tar on Pillsbury biscuits. "The customers called it 'brown bread,'" she recalls.

|

|

|

Jay Pickthorn |

Every Saturday, Sanaa Abourezk herself begins by making the dough for mana'esh. A native of Syria, she came to the

us to pursue a doctoral degree in citrus farming. She already had a degree in agricultural

engineering—her father's dream, so that she could help manage and improve the family's successful farm in Syria. But her

soul was in cooking, and fate would lead her in that direction. Twenty years ago, she met and married former us Senator James

Abourezk, an Arab-American, who returned to his native South Dakota after retiring from Washington politics in 1979. For a while,

Sanaa was happy writing cookbooks that highlighted healthy, mostly vegetarian Middle Eastern food and raising their daughter, Alya,

now 15. Then one day, seven years ago, she saw a warehouse along the railroad tracks that was being turned into retail space.

Without really having a menu planned out, she nonetheless decided to go for her dream, so she opened a restaurant that initially

served soup and Pillsbury biscuits baked with a light sprinkle of olive oil and za'tar.

|

"People loved it," Sanaa recalls. "The customers called it 'brown bread,' and soon I was making it with my own dough.

As the menu expanded, the brown bread became an appreciated necessity of our menu."

It isn't brown bread to everyone, of course: The Dakotas actually have a long history of Arab immigration, with many coming over

in the 1890's, when the area became the last region where a penniless immigrant could receive 160 acres (65 ha) of free land under

the Homestead Act of 1864—provided he was willing to endure the winters. Still other Arab immigrants came as "prairie

peddlers," itinerants selling to homesteaders, and some of those eventually opened their own general stores. In fact, Sanaa's

husband was born on a Native American reservation where his Lebanese parents had a store.

|

|

Jay Pickthorn |

|

Abourezk keeps her best za'tar in a freezer, and she often makes the mana'esh herself, right.

|

"There was another Arab family, the Abnors, who lived about an hour from us, and every Sunday we'd get together for dinner,

" the senator recalls. "We ordered our Arab food, including za'tar, from Sahadis in New York, and it would get shipped

out to us. Aside from grape leaves, which my mom used to pick wild, the food I remember most is za'tar."

The former senator has his own table at Sanaa's, where he can be found every day, and where aspiring politicians and local

businessmen grab seats to share political news and gossip. Members of the Sioux Falls Arab community stop by with their own

za'tar experiences.

"I loved za'tar, but I didn't want my grandmother making it when I had other kids over," recalls historian and writer

Mike Saba, whose grandparents were homesteaders. "I was kind of embarrassed by za'tar. I didn't want kids asking 'What's

that dirty bread you're eating?'—because that's what it looked like to others."

|

|

Jay Pickthorn |

|

Son of immigrant Lebanese grocers on a Native American reservation, us Senator James Abourezk,

seated, center, retired since 1979, often spends a few hours each day in his wife's restaurant.

|

Sioux Falls newcomers from Arab countries, mostly doctors and engineers, still go back regularly to the Levant to visit their

parents and other relatives. They all bring back za'tar, as they must to survive without a Middle Eastern grocery in town.

Lebanese-Palestinian Salwa Koutally, one of Sanaa's close friends, brings za'tar back for all her adult children, and when she

makes mana'esh, she sends some by overnight courier to her son in New York. A doctor who has lived in Sioux Falls for 15 years

says, "My sister always prepares za'tar for me to bring back when I go visit," explaining that it's because "my

village has the best za'tar." "No, it doesn't," another customer interjects. "Everyone knows my

village does!" And then—not for the first time—a good-natured argument starts about where the best za'tar

comes from.

"Za'tar can be a very personal thing," says Sanaa with a smile. "It's private. Some people have their own

stash of wine; I have my own stash of za'tar." The restaurant's za'tar, she confides, comes from Jordan via her Middle

East food supplier in New York. But hidden in her freezer is a plastic bag of dried za'tar leaves from the mountains in

Syria. Its woodsy, citrusy aroma hits you as soon as she opens the bag. Also nestled in the freezer is one of her favorite

za'tar mixes from Damascus. There, the scent of anise is unmistakable. "What I love about za'tar is the little surprises

that make each mixture unique," says Sanaa. "For example, sometimes people add rosemary, cayenne, cumin or fennel

seeds."

Sanaa favors her mother's za'tar, which contains ground roasted chickpeas. "The chickpeas were added when people

couldn't afford pure za'tar," says Sanaa. "In truth, it was a good decision, because chickpeas add protein,

making our breakfast even more nutritious."

Sanaa's "brown bread" is now sold at the local co-op. "It comes in on Thursday afternoon and is gone by

Friday," says Molly Langley, the store's manager. It is, she adds, "a step up for food connoisseurs looking for

unique and delicious options." Sanaa has also created other ways to serve za'tar. On Friday nights, she tops her

"brown bread" with a tomato, onion and pepper mix for a little extra kick and color, and she adds za'tar to her

fattoush salad. "Za'tar provides that same tang, and the sesame seeds add extra texture," she explains.

|

Back in the Levant, similar creativity is bubbling. In the past, za'tar was mostly for dipping with olive oil, for spreading

on mana'esh or for sprinkling on the sesame bread rings sold by street peddlers. Today za'tar has leaped off the mana'esh

and into croissants, onto toasted almonds and into just about any other place it can be sprinkled. In Amman, across the street

from Izhiman, Sufara, a giant bakery, seems to put za'tar in everything that comes out of its ovens—breads, cakes,

cookies and crackers. In Beirut, any upscale supermarket features an expanding array of products containing za'tar.

"When I said I was going to write a book about the man'oushé, people thought I was strange, but I think it

was so successful because it portrayed who we are," says Barbara Massaad. "Za'tar brings smiles."

"Za'tar is an important regional identity," says Carol Cherfane. "It is the Middle East Arab crop. Just look

at these things I got at the Beirut airport yesterday." She offers a tin of crunchy little tidbits—a new za'tar

creation. One way or the other, za'tar always seems to find its way to the airport, and beyond.

|

|

Right: Jay Pickthorn |

|

|

Right: Jay Pickthorn |

|

Top, left to right: Nabil Kamal Eldin slides mana'esh into his bakery oven in Batloun, Lebanon, much as

Sanaa Abourezk does in Sioux Falls. Above: Izhiman and other spice shops offer taste-tasting and custom

za'tar mixing; Sanaa includes her popular "brown bread" on her buffet line. Mana'esh for sale in Amman,

below left, and Sioux Falls, below right.

|

|

|

Right: Jay Pickthorn |

|

Alia Yunis

(www.aliayunis.com)

is a writer and filmmaker based in Abu Dhabi. She is the author of the critically acclaimed novel The Night Counter (Random House, 2010). |

|

Photographer and writer

Tor Eigeland

(www.toreigeland.com)

has covered assignments around the world for Saudi Aramco World and other publications, and has contributed to 10 National Geographic Society book projects. |