Written by Louis Werner

Photographed by Kevin Bubriski

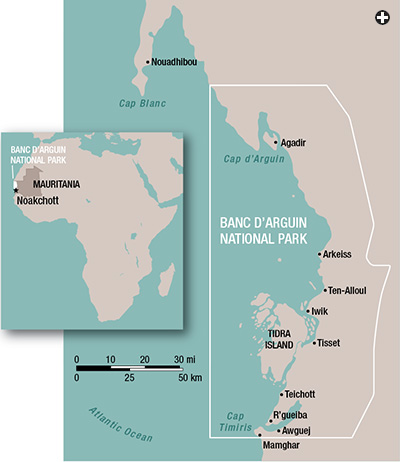

ellow dunes and blue sea mark the mudflats and

sandbars of the Banc d'Arguin, which begins on the west coast of central Mauritania and extends into the Atlantic Ocean

for almost 150 kilometers (93 mi).

ellow dunes and blue sea mark the mudflats and

sandbars of the Banc d'Arguin, which begins on the west coast of central Mauritania and extends into the Atlantic Ocean

for almost 150 kilometers (93 mi).

The Banc and its gulf, now part of the 1.2 million-hectare (4633 sq mi) National Park of the Banc d'Arguin, is

proclaimed "notorious as a danger to navigation" on the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, the authoritative

atlas of undersea hazards, but its vast, shallow expanse is also one of the world's richest wintering sites for

wading and water birds.

Try looking through the binoculars for ruddy turnstones, greenshanks, white pelicans, black-backed gulls, sooty

shearwaters and grey herons. If you prefer pink, focus in on some 40,000 flamingos, whose delightful scientific name

is Phoenicopterus roseus. Or just call them nanya in Hassaniya, the local Arabic dialect.

It is even more difficult to overlook the million-plus short-legged dunlins, also known as red-backed sandpipers;

they make up at least a quarter of the species' total world population. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

the dunlin calls out with a "raspy krree" and is "highly gregarious in winter." The

Banc's huge flocks confirm both statements. No wonder the bird's status at the International Union for Conservation

of Nature (iucn) is of "least concern."

Add to the named species the occasional pipers, pipits and plovers, the snipes, storks and stints, also oystercatchers,

godwits, cormorants and terns, and songbirds like warblers, wheatears and red-rumped swallows. Circling high above

them all are the griffon and Egyptian vulture. All told, some three million birds, of some 300 species, can be found

in the park in winter.

What makes the Banc unique is not only its network of shoals and flats, rich with seagrass and relict forests of Avicennia africana,

West Africa's northern-most mangrove species, named after the 11th-century Persian polymath Ibn Sina. These waters are also the

coastal confluence of the warm Guinea Current, which flows up from the south, and the cold Canary Current that flows from the north.

Their convergence causes an upwelling of colder water heavy with fish food, a rare event anywhere south of the Tropic of Cancer.

What is a boon to fish and sea life is thus also one to birds, and the complex food chains that result turn and twist

upon themselves. Fish-eating jackals and ospreys meet seagrass-eating redknots and fiddler crab-eating whimbrels. Larger

bonito and corvina feed on smaller sardines. At low tide, when some 500 square kilometers (193 sq mi) of mudflats are

exposed, everyone seems to chase worms and crustaceans, which themselves are fattening on algae and plankton.

|

Théodore Monod, French naturalist and expert on the Sahara, was one of the first to recognize the Banc's unique

ecology, and in 1976 the Mauritanian government created the park to help protect it. Since then, the region has been named

a unesco heritage site and a "critical wetland" under the Ramsar Convention on

Wetlands. The Swiss Fondation Internationale du Banc d'Arguin (fiba) is among several

organizations that support the park's founding mission of harmony between the region's human environment and natural

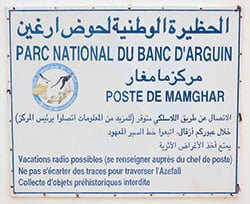

conservation. While park rules restrict economic activity to camel herding and net fishing from sailboats, this year the

government opened welcome centers at the park's two entrances and trained ecotourism guides in the park's eight villages,

in addition to encouraging the production of fish-based products for export.

The eight villages within the park are home to some 1400 Imraguen, a name of Berber origin meaning something close to

"fishermen," even though they, like most Mauritanians, speak Hassaniya. The most spectacular way to enter the

park is along the 65-kilometer (40-mi) beach drive, which is passable only at low tide. Cap Timiris, site of the park's

most populous village, Mamghar, is one of West Africa's important headlands, as notable a landmark from sea as Dakar's

Cap Vert, Nouadhibou's Cap Blanc, and Tarfaya's Cap Juby. Here the fishing turns from semi-industrial outside the park

boundaries to artisanal inside the park, from motorboats to sailing craft. And here too is where, in the fall, the women's

cooperative turns out kilo upon kilo of the area's best poutargue—pressed, dried mullet roe—during

the annual yellow-mullet run along the coast. It is up to co-op member Asseitu mint Khatri to extricate the egg sac from

the fish, grade the eggs, then press, dry, bag and freeze them for sale.

Poutargue is itself a loan word from the Arabic boutaarikh, found in the Egyptian colloquial dictionary

as a verb meaning "to be swollen, as fish with eggs or a wallet with money." Its origin may be from the Greek

tarichos, meaning "dried fish." Lately the Italian Slow Food Foundation is working with local women to

market Mauritanian poutargue in Europe, where it may win favor over local but lower-quality dried gray mullet roe, a delicacy

shaved onto pasta like aged Parmesan cheese.

From Mamghar across the Baie de Saint-Jean is R'gueiba village, home to the park's only boatyard. Mohamed Fadel ould

Mahfoud, president of the boat builder's cooperative, is one of eight trained ship's carpenters who maintain the park's

authorized fleet of 114 sailboats. Power-sanding the ribs for a new, 11-meter (36') boat—configured not unlike the

ribs of the whale skeleton on display at the park's headquarters—he explains the importance of the boats. "Without

boats, and without wind, we would not eat," he says.

|

Bouthia ould Bah, the Park's chef de poste, or warden, has had to handle the occasional dead whale that has washed

up on the beach during his 15 years here. But his job mainly consists of taking three radio calls a day, making sure fishermen

use the required biodegradable nets rather than monofilament lines that can trap and kill wildlife, and counting the day's

catch. As it comes into the fishermen's co-op, ice boxes keep tilapia, dorado (n'tad in Hassaniya), corvina, mullet

(zuwhol) and bream (hout al-ahmar, or "red whale") fresh.

Quickly changing tides and shifting winds in the Baie de Saint-Jean give the working sail fleet both a challenge and an

advantage for corralling fish. Since the bay recently reopened, after a three-month fallow period at the end of last year,

it is teeming again. To R'gueiba's fish market has come nearby Teichott village mayor Mohamed Lemine Teba, who is looking to

buy bonito, considered the best food fish in these waters. Here it fetches up to three dollars per kilo. What these warm

shallows do not offer, however, are the delicacies caught farther offshore or along the rocky Atlantic coast of Cap Blanc:

octopus, lobster and cuttlefish.

Teichott sits opposite the south end of Tidra Island, the park's largest, ringed at low tide with relict mangrove and seagrass

(Zostera noltii) beds. The former provide resting spots for egrets, herons and cormorants, while the latter shelters

the birds' favorite fingerling prey. The village's sail fleet anchors far off the beach at low tide, so returning fishermen

must wade 100 meters (330') to shore, fish trays balanced on their heads. Park warden Ely ould Bouyah rechecks the nets for

prohibited small-mesh gauges that prevent the escape of smaller fish. The mullet catch ends by January, but it overlaps with

catfish, which this winter can be found being gutted and deheaded, thrown into sand pits and covered with rock salt and a tarp

for five days to preserve them. The barbed dorsal fins make it a tough job even for a gloved hand wielding a sharp knife. Gulls

swoop overhead, waiting for offal buckets to be tipped in their direction.

Just up the coast is Iwik village, the Park's central headquarters, just by Tidra Island's northern end. Here Captain Deidah

ould Jedeidu, with first mate Yacoub ould Abdullahi on board a boat named Jadda ("grandmother"), sets sail

with a Canary Islander lateen rig rarely used anywhere but here. In this configuration, the yard is pushed around the mast when

changing tack in order to maximize airflow, which requires constant fine-tuning with a bottom sail spar.

Deidah's nautical terms are a mix of Spanish and Arabic: The sheet is a cota (from the Spanish escota); the

yard is a balanka (from the Spanish palenque, "rail"); but he uses the Arabic words for anchor

(mirsah) and fishnet (shabaka). Starting out from port at low tide means skirting the nearest mudflats,

those they call Jinjan, which impede access to open lagoons and the rich fishing grounds around Tidra, Nair and Niroumi islands.

Some 10,000 spoonbills (Platalea leucorodia; m'boye in Hassaniya) come here from northern Europe in winter, and

it seems that Otto Overdijk, from the Dutch conservation organization Natuurmonumenten, knows each one personally. Otto

is the world's foremost expert on the spoonbill, and he has been coming to the Banc d'Arguin for some 15 years from his

base in the birds' main summer nesting ground in Holland's Waddenzee. He has personally banded some 8000 spoonbills, mostly

back in his home country, each with a unique sequence of colored rings, three per leg, a configuration easily identified

through the spotting scope he carries around like a third eye.

His data set contains some 112,000 positive sightings, at both ends of the migration route, of some 14,000 banded birds.

One bird banded in 1999 has been seen more than 100 times. Another, which he banded when it was less than three weeks old

in June 2009 on Schiermonnikoog Island, stayed within 28 kilometers (17½ mi) of its nest until it started its first

winter migration to the Banc d'Arguin. It was spotted here a year later and is likely to stay put for four years. Then,

as an adult, it will return north to its own hatching site to breed.

Overdijk is not surprised to see a bird return to build its nest within a meter of its hatching place even after the four

intervening years of its first African sojourn. Then it continues to make the migration an annual winter affair. (That bird

hatched in June 2009 in Holland was last seen in the park on January 7, 2012, its band color code as readable to Overdijk

as a familiar face: On the left leg, metal, yellow, blue; on the right leg, yellow flag (indicating Dutch-born), yellow,

lime green.

In fact, 2500 spoonbills are yearlong residents, born here (indicated by a red flag band) and given the subspecies name

Platalea leucorodia balsaci, while the others make the 4000-kilometer (2500-mi) annual migration, mostly to

Holland, Denmark and Germany. Year-round residents have a completely black bill, while the winter visitors have a dull

orange spot at its tip. On both, breeding plumage is an ochre chest patch, a red neck stripe and a yellow crop—an

elegant combination.

Spoonbills usually lay four eggs, which incubate for 26 days. Chicks then spend seven weeks in the nest. Like most nesting

water birds, spoonbills shift from tidal to diurnal rhythms, from sleeping at high tide and feeding at low tide, oblivious

to day or night, to an incubating pattern in which the males take the night shift and the females take the day.

Overdijk knows all this because in July 2008 on Nair Island, just north of Tidra, he fitted one bird, which he nicknamed

Abou, with an Argos satellite transmitter, whose location readings are accurate within 10 meters. Abou's breeding habits

were tracked over the following years by noting when its feeding habits changed from a tidal to a diurnal schedule. With

its nest above the high tide mark, it no longer moved with the tides, only with the rising and setting of the sun.

Not all waders, however, are low-tide feeders. Above the high-tide line, beaches are pitted with the holes of fiddler

crabs, who busy themselves feeding outside their lairs on full-moon nights when their chief predator, the whimbrel,

can also be heard making noises that to human ears sound joyful. When caught out in the open, the crabs make a break

for the nearest hole—which they often find occupied. Then they are pushed out from behind to a certain death,

skewered on a whimbrel's long, sharp beak.

Spoonbills and flamingos have an advantage over shorter-legged waders: They can feed longer on the rich mudflats as

the tide comes in. There they are also safer from jackals and hyenas, whose splashy attacks are easily heard. Spoonbills

also rely on the more skittish gray herons to act as sentinels. When the herons fly at the approach of danger, the

spoonbills know they have just a few more moments to feed before they too must depart.

Familiar as he is with the end points of the spoonbills' migration route, Overdijk is most worried these days about

their stopping places en route. Because the trip burns the caloric equivalent of 1200 grams of fat, but the birds are

only able to fatten 600 grams above their average weight of 2½ kilograms (5¼ lbs), they must make a complex

choice. They must either migrate in two equal legs of 2000 kilometers (1250 mi) each, stopping once in southern Spain to

fully refatten themselves during a two-month rest, or they must stop every five days along the entire route, gaining some

50 grams at each layover. Such short hops lessen the fatal risk that the once-only feeders face if food at their layover

turns out to be unavailable, yet it also requires more protection for their intermittent stopovers. "Where they stop

on land in their migration is just as complex and delicate a matter as where they fit into the aquatic food chain,"

says Overdijk.

Spoonbills are not the park's longest-distance migrants. Overdijk has found a Canadian-banded ruddy turnstone here.

Scotland's Highland Foundation for Wildlife tracked an osprey to the park from the Firth of Moray. And what of the red

admiral butterflies flitting around the Spartina grass? They too have come to spend the winter far from the

cold of northern Europe.

Two hundred kilometers (125 mi) north of the park, just off Mauritania's chief fishing port of Nouadhibou, Hamdi ould

M'barek worries not about sea birds but rather about a single species of sea mammal, the monk seal (Monachus

monachus), high on the iucn's Red List as one of the most endangered animals in the

world. He is field director for Spain's cBD-Habitat Foundation, and founder of the local group Annajah, which promotes

fishermen's education and women's income projects.

Monk seals were once common both here and throughout the Mediterranean. Portuguese chronicler Gomes Eanes de Zurara,

describing an expedition led by Afonso Gonçalves Baldaia in 1435 on behalf of Prince Henry the Navigator, wrote

of seeing them in a bay just to the north of Nouadhibou: "And when he saw a huge multitude of sea wolves whose

number reached five thousand, he ordered that as many as possible be killed and that the hides be loaded onto his ships.

Perhaps they were easy to kill, or perhaps his men were skillful, for great numbers were so slaughtered."

Cap Blanc's wave-beaten and cliff-lined Atlantic coast, dotted with sandy bottomed caves, is home to the world's largest

colony of this warm water-loving species. After a catastrophic die-off in 1997, probably caused by a red algae, the

colony has rebounded in recent years. Last year, 55 pups were born, bringing the population close to 300. Conservationists

are guardedly optimistic that the species can survive, after having been eliminated from the Mediterranean.

Hamdi is responsible for a six-kilometer (3¾-mi) stretch of coastline on what was previously the seaward territory

of Spanish Sahara. It is still laced with land mines, so his wardens watch their steps as they move along known safe

routes to flagged observation posts. (In 1988, four conservationists died in a mine blast.) The wardens' job is to wave

off motor launches that approach the coast and to report illegal lobster nets so the team's motorboat patrol can remove them.

Little is known about the monk seal, but it is abundantly clear that the Arabic word for seal, 'ijl al-bahr, or

"sea calf," makes perfect sense, as 'ijl comes from the verbal root meaning "to be speedy."

One thing that Hamdi's satellite tracking of three individual seals has shown is that males try to maintain exclusive

breeding territories, not feeding territories as was previously thought. (The three seals that are currently tail-tagged

are affectionately named Woody, Trebol and Champollion—not in honor of the French decipherer of the Rosetta Stone

but to commemorate the last monk seal in the Canary Islands). The color-coded chart of their swimming patterns during

breeding season, usually the first months of the year, show that they keep close to shore.

One dominant male may keep up to 30 females to himself. He typically makes 70-meter (230'), eight-minute-long dives for

lobster and octopus during his three-day feeding forays, during which he must eat 10 percent of his 300-kilogram (660-lb)

adult body weight each day. That's followed by a two-day sleep-a-thon. Yet there remains little chance for an intruding

male to make his move. Some repulsed juvenile males set off to explore farther shores, and some have turned up in the

shallows of the Banc d'Arguin.

The team keeps a photo book of individual seals identified by their marks—either their coat's spot patterns if

they're pups or their scars, caused by being surf-tossed against rocks, if they're older. Some are given pet names based

on the markings, such as Gaviota ("seagull" in Spanish, the working language on Hamdi's team), Half Belt, Doughnut,

Parenthesis and Nike—this for a swoosh-like scrape).

The log shows that Gaviota is 15 years old, and she has pupped eight times, producing five males and three females,

always around the same day in August. Since a pup's spots fade over time, wardens must watch closely for a distinctive

rock-scrape pattern to emerge before its spots disappear completely. A full telephoto census of individual seals is taken

along this coastline one week each month, in addition to the live video feed from the cave interiors that is recorded on

computer hard drives. To fast-forward through the first three months of life in a monk seal pupping cave is surely to see

a conservation success story in motion.

Luckily for observers, female pups are born with a black-spotted, square, white belly patch and males with a similarly

colored arch-shaped patch, so it's easy to assign the correct sex to every newborn. Each pup is given a birth certificate

of sorts, with its sightings recorded by date and behavior. For instance, #575 was born to female #2032 on August 8, 2011,

weighing 18 to 20 kilograms (40-45 lbs) and measuring one meter (39") long. Its first photo was taken a day later. Three

months later, it was identified playing in the water near the cave, its sponge-like black birth hair, which would have

become waterlogged had it dared to swim in its first two months of life, now shed and replaced with water-repellant gray fur.

While most of the seals stay along this limited stretch of coast, a few loners have taken off to points farther afield.

One such pioneer has chosen to homestead at the very tip of Cap Blanc, where an overlook gives the visitor a 270-degree

panoramic view west into the Atlantic, south into the Banc d'Arguin's gulf and east into Nouadhibou's Baie du Levrier.

And here, high on the beach, sits the United Malika, a Moroccan freighter that ran aground in August 2003, now

a hulk attended to by a crew of Malian ship breakers salvaging iron and steel by the kilogram.

Painted on its side is a poem, a lesson for sailors leaving home in search, as the last line has it, of profit in

Moroccan and Mauritanian realms. The words apply as well to men aboard ship as they do to birds in the air and seals in

the sea, even if the birds are flying to nests thousands of miles away, and the seals know better than to stray far from

their pupping caves.

We are shipmates sailing out across the sea,

All speaking the same language,

All worshiping the same God.

All people are like brothers; to them we give our greeting,

And our dirham and ouguiya, aglitter both like gold.

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com) is a writer and filmmaker living in New York City.

|

|

Kevin Bubriski (www.kevinbubriski.com) is a documentary photographer and professor of photography at Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont. |