People have long used fear as a tool to entertain.

Tales of monsters have been with us since the dawn of time. They are part of every

people’s traditions and folklore, whether told around a prehistoric campfire or projected on a wide screen

with digital sound for 21st-century audiences.

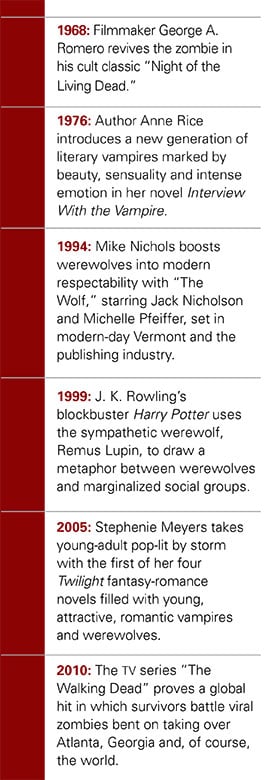

|

|

|

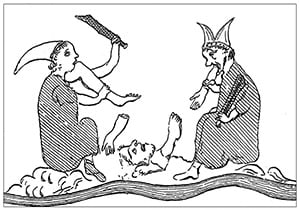

british museum / art resource |

| The Epic of Gilgamesh, shown here in part of the 11th tablet, mentions several

types of monsters, and an older Sumerian tale says Gilgamesh's father was a Lillu, or blood-sucking demon.

|

In all the stories, the monsters take their shapes from our fears of the unknown—be it apprehensions

about nocturnal noises from a forest, or worries over the ominous intentions of races in far-off lands

described by returning sailors. Evidently, some monsters that first materialize on a remote continent find

ways to migrate to one’s own land and take up residence in a nearby wilderness or wasteland.

In the Middle Ages, Europeans believed that most monsters originated on other continents, and they often illustrated

their maps and sea charts with images of the fantastic creatures in these half-legendary lands. The 13th-century

Hereford mappa mundi (world map) is an outstanding example: Pictures of fabulous races and animals are

distributed all over the globe,with India and Ethiopia displaying the main share. In India live the single-legged

beings called sciapodes; the pygmies and the giants; the mouthless people; the manticore, or man-lion; and the

unicorn. North of India, in Scythia and bordering countries and islands, there are horse-hoofed men, people with

long ears and grotesque cannibals called Anthropophagi; in the Arctic are giant Hyperboreans; and in the Carpathian

foothills are the one-eyed Arimaspians, who were said to fight with the griffins. Ethiopia is inhabited by satyrs

and fauns; by people with long lips and others with their heads in their chests; and by basilisks and gold-digging ants.

In the 21st-century entertainment world, we relish our own menagerie of monstrosity, from alien invaders to dinosaurs,

dragons, ghosts, giants and robots running amok. Some, like Egypt’s mummies, Arabian Nights genies and their

cousins, the ghouls, clearly originate in the Middle East, which is fitting, given that it’s the home of some

of the earliest human civilizations.

But what about three of the most enduring and currently popular world-class monsters: the vampire, the werewolf

and the zombie? These three particularly continue to terrify, thrill and intrigue us like no others. All three, it

turns out, have traveled great distances to be with us. But in their modern forms, none has obvious family ties to

the Middle East. The driven, blood-craving vampires and the vicious, shape-shifting werewolves originate in the

folklore of Hungary, Romania and Greece—or so we are told. Zombies, classically viewed as resurrected corpses

or “the undead,” derive from New World Voodoo traditions—or so we are told.

There is evidence, however, that all three in fact arose from the most ancient tales from the Middle East. As we

shall also see, the closer we investigate, the more the Arabian ghul keeps leaping out from the shadows of

history to drag us into its mythical lair.

The vampire is usually a revived corpse or quasi-living being that maintains its existence by drinking human blood.

Some experts assert that the vampire originated in ancient Egypt or India, but those connections are tenuous. The first

creatures that actually fit the modern description of vampires appear in the surviving writings from the Fertile Crescent,

in texts from Assyria in the north and the Akkadian and Babylonian empires in the south, as well as in documents of the

earliest known Mesopotamian civilization, Sumeria.

Assyria, on the upper Tigris River, in what is now northern Iraq and parts of Syria, endured from about 2400 to 600

bce and was ruled from Assur (or Ashur). The Assyrians

adopted beliefs from their Sumerian predecessors, including belief in two classes of demons with vampire-like tendencies:

the ekimmu and the utukku. The ekimmu were the angry spirits of persons dead but unburied,

prowling the earth until they found rest beneath the ground—a characteristic phase of the traditional vampire.

An utukku was sometimes hard to distinguish from the ekimmu, but generally it was the spirit of a

deceased person who had been buried but forgotten, not honored with offerings at its tomb by family or loved ones.

As a result, the utukku returns from the underworld to haunt whomever it encounters, seeking sustenance from

its victims. Like the vampire of Eastern Europe, this creature is a persistent haunter that is very difficult to dislodge.

Sometimes the utukku are blood-drinkers, while at other times they are said to imbibe the human life-force.

While they are most often malevolent, on occasion they can be allies, and such an utukku appears as Ea-Bani,

friend of Gilgamesh.

A particularly vivid description of a group of thoroughly evil, vampire-like utukku known as the Seven Spirits

appears in a 3000-year-old Assyrian cuneiform incantation:

Seven are they!

Knowing no care,

They grind the land like corn;

Knowing no mercy,

They rage against mankind;

They spill their blood like rain,

Devouring their flesh [and] sucking their veins....

They are demons full of violence,

Ceaselessly devouring blood.

Translator R. Campbell Thompson, in his authoritative Semitic Magic, says the Seven Spirits’“predilection

for human blood … is in keeping with all the traditions of the grisly mediaeval Vampires.” Thompson notes that these

Seven Spirits reappear later in both Palestinian and Syriac magic spells. A Syriac charm from Christian times quotes the

Seven as saying: “We go on our hands, so that we may eat flesh, and we crawl along upon our hands, so that we may

drink blood.” But the Assyrian incantations and their successors make it clear that vampirism was but one characteristic

of these demons that also traveled with storms, like wind demons, and that ate flesh, like Arabian ghouls.

Earlier than the Seven Spirits were the blood-sucking vampire-demons of Sumeria. A manuscript recording the kings and

dynasties of Sumer, dating from about 2400 bce, asserts that

the father of the Sumerian hero Gilgamesh was in fact a Lillu-demon. This Lillu was one of four demons in a class of

vampires: The other three were Lilitu (manifested in later Hebrew tradition as Lilith), the female version of the vampire

demon; Ardat Lilli (or Lilitu’s handmaid), who visited men at night and bore them ghostly children; and Irdu Lilli

(Ardat Lilli’s male counterpart), who would visit women at night and make them pregnant. Lilitu was believed to be a

beautiful, promiscuous vampire, similar to some 21st-century literary versions, partial to the blood of children, infants

and young men. From Sumer, Babylonians and eventually Hebrews adopted versions of these legends, and similar traditions

developed in northern Mesopotamia.

|

Many of the traditions in early Hebrew literature, including monster folklore, derived similarly from the beliefs of

Mesopotamia. Although some scholars have claimed that there is no trace of vampires in early Jewish literature, this is not

accurate. The book of Proverbs (30:15) refers to a “horse leech” or bloodsucker (Hebrew

‘alukah): “The horse-leech hath two daughters, crying: Give, give.” Old Testament

scholar T. Witton Davies says this creature is not a common leech but instead “probably a vampire or blood-sucking

demon,” and he notes that several other prominent scholars support this interpretation. One biblical translation,

the Revised Version, offers a marginal note for “horseleech” that states, “Or, vampire.” The

International Standard Bible Encyclopedia agrees that something similar to a vampire is intended in light of the similarity

between the Hebrew word ‘alukah and the Arabic ‘aluqah, which means female ghoul. Indeed, the

Jewish Encyclopedia of 1906 declares that the ‘alukah is “none other than the flesh-devouring ghoul of

the Arabs…. She has been rendered in Jewish mythology as the demon of the nether world … and the names of her

two daughters have in all probability, as familiar names of dreaded diseases, been dropped.”

Another popular vampire-demon of the Hebrews—borrowed, as we have seen, from the Mesopotamians—is Lilith.

Early Jewish legends say Lilith was the first wife of the first human, Adam, created from clay rather than from Adam’s

rib, as Eve later was. According to some accounts, Lilith refused to be subservient to Adam, and she abandoned him along the

Red Sea coast, where she consorted with demons and bore vast numbers of demon (or jinn) children. She herself evolved

into a night demon with an abiding hatred for human children, and she would come in the night to suck the blood of infants.

She was also sometimes portrayed as a bird, often an owl.

|

|

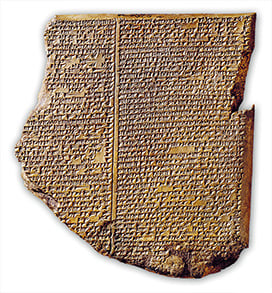

british museum / art resource |

| A woodcut portrait dated 1491 shows Transylvanian Prince Vlad Tepes iii,

whose cruelty in fighting the Ottomans earned him the sobriquet “the impaler.” He was neither a count nor

did he drink blood: “Count Dracula” was created in 1897 by Irish author Bram Stoker. |

Are these early Middle Eastern vampire creatures related to the more human-like European vampire, the folkloric creature

popularized in 1897 by Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula? Could such beliefs have found their way into Eastern

Europe? If we consider that ancient Greece may have been the gateway for the migration of a wealth of Mesopotamian ideas

and legends, it may be so. There is growing evidence that Greece experienced a rich infusion of mythology and folklore from

the Middle East between the 12th and ninth centuries bce. Charles Penglase, author of

Greek Myths and Mesopotamia, argues that the Homeric hymns and the poems of Hesiod, written in the seventh century

bce, show influences from the myths and religious beliefs of ancient Mesopotamia:

“Mesopotamian religious and mythological material could have reached Greece at earlier periods, but the influence

apparent in these works seems to be a result of contacts in the period of intensive interaction in the first millennium

bce, beginning in the middle of the ninth century bce. The

late Mycenaean time before the end of the twelfth century bce has also been suggested by some

as a time of influence, owing to the extensive contacts between Mycenaean Greece and the Near East at this time.”

The Greeks developed their own version of the Mesopotamian vampire-demon Lilitu, which they called the lamia. Named for

a demon born in Libya who terrorized Europe, the lamia had the face and upper body of a woman and the tail of a serpent.

Lamias could disguise themselves as human women. They devoured children and sapped the life-force from men. Lamias became a

staple of Greek folklore and spread to other European lands, including France, where a lamia named Melusine magically concealed

her blue-and-white serpent’s tail, married a French nobleman and, repurposed as a “water fairy,” became

part of Europe’s colorful legendary tradition.

Romania has some of the richest vampire lore in Eastern Europe. Its scenic central region, Transylvania, bounded by the

Carpathian Mountains in the east and south, was the setting for Stoker’s Dracula. Count Dracula, played in the

1931 movie version by Bela Lugosi, was Stoker’s vampirized rendition of an actual person: Vlad iii

Dracula of Transylvania, who lived from 1431 to 1476. A Wallachian noble who waged war against the Ottoman Turks, he became

known as “Vlad the Impaler” for his reputed execution, many by impalement, of 20,000 or more Turkish soldiers—but

no one has ever suggested he drank blood.

Romania may have absorbed some of its vampire traditions from Greco-Roman sources, which in turn had taken them from the

Middle East. Romania and its heartland, Transylvania, were part of the Greek-influenced Thracian kingdom of Dacia from 86

bce and then part of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271 ce.

It makes sense that the Romanian name for vampire is strigoi, derived from strix, the Roman and Greek

word for “owl.” In Greek and Roman folklore, the strix was an evil bird, capable of shape-shifting, that

fed on human flesh and drank human blood. Its exact nature remained something of a mystery, even to natural history experts

like Pliny the Elder, but it appears to be another example of Mesopotamian influence, given that Lilitu-Lilith was a vampire

and at times portrayed as an owl. In the British Museum, on a bas-relief known as the Burney Relief, an image of Lilitu from

ancient Babylon appears, often dubbed “The Queen of the Night”: a human female figure with feathered bird wings

and bird claws for feet.

Some vampire lore may also have entered Eastern Europe through the Turks. In Hungary, for example, the belief in vampires

is said to date back to accounts from the 12th century that cite a demon called izcacus, or blood drinker. This

word’s origin dates back before the Hungarians’ arrival in Europe from Central Asia in 895. Turkic culture expert

Wilhelm Radloff says the word has its roots in ancient Turkish, which the Hungarians encountered during the late eighth century

in regions between Asia and Europe. Migrating Turkic tribes may have acquired vampire lore from settled populations in western

and Central Asia that had been influenced by the Assyrians and their successors.

The earliest known literary account of a human transformed into a wolf appears in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, probably

the oldest written story on Earth, dating back more than four millennia. Originally written in cuneiform script on 12 clay

tablets, it is the story of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk in what is now Iraq. In the tale, Gilgamesh is courted by the goddess

Ishtar, but he rejects her and reminds her of the tragic fate of her previous lovers:

You loved the Shepherd, the Master Herder,

Who continually presented you

with bread baked in embers,

And who daily slaughtered for you a kid.

Yet you struck him, and turned him into a wolf,

So his own shepherds now chase him

And his own dogs snap at his shins.

Assyriologist Julius Oppert asserts that belief in the werewolf was a part of the ancient Assyrian worldview. Later,

widespread belief in werewolves may have contributed to a psychiatric disorder in King Nebuchadnezzar ii,

who ruled from about 605 to 562 bce, in which time he destroyed Jerusalem’s First Temple

and built the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the original “seven wonders of the world.” It also appears, from

the Biblical Book of Daniel, that Nebuchadnezzar suffered from what psychiatric experts Harvey Rosenstock,

md, and Kenneth R. Vincent, ed.d., have described as “depression

that deteriorated over a seven-year period into a frank psychosis, at which time he imagined himself a wolf.”

|

This is more broadly known as lycanthropy (“wolfman-ism”), or delusions of being a wild animal (usually a wolf),

and it is a disorder that has been recorded since antiquity. Among the earliest medical descriptions of it is one from the

Byzantine Greek Paul of Aegina, a highly regarded physician of the late seventh century, who describes it with reference to

the Greek myth in which Zeus turned King Lycaon of Arcadia into a raging wolf.

Like the vampire, the werewolf appears to be a migrant from the Middle East to Greece, where it surfaced in this legend.

According to the most popular version, repeated by Ovid and other Greco-Roman authors, Zeus visited Arcadia in human form

and dined with King Lycaon. The king doubted his visitor was Zeus and tried to test his divinity by serving him a dinner of

human flesh. Zeus punished Lycaon by transforming him into a wolf.

Pliny, in his Natural History, relates another old Greek story about a man of the family of Antaeus, who was

selected by lot and brought to a lake in Arcadia. There, he hung his clothing on a tree and swam across. When he reached

the other side, he was transformed into a wolf, and he wandered in this shape for nine years, living with wolf packs.

After the nine years had elapsed, if he had attacked no human being, he was free to swim back and resume his human shape.

Set in Arcadia as it is, this tale may contain echoes of the Lycaon story.

Herodotus wrote of werewolf legends in his Histories, telling about such a tradition among the Neuri, a possibly

Slavic people northeast of Scythia who had adopted Scythian customs. “It appears that these people practice magic,”

he wrote, “for there is a story current amongst the Scythians and the Greeks that once a year every Neurian turns into

a wolf for a few days, and then turns back into a man again.” Herodotus comments: “I do not believe this tale; but

all the same, they tell it, and even swear to the truth of it.”

|

|

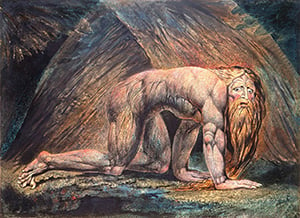

tate gallery / art resource |

| King Nebuchadnezzar ii of Babylon may have suffered from a

psychiatric disorder known as lycanthropy—the belief that one is a wild animal, most commonly a wolf.

English artist and poet William Blake immortalized the king’s agony around 1805. |

This too may have roots to the east. The 18th-century Swedish historian Olof von Dalin wrote that the Neuri were a composite

of Scythians, Greeks and Hebrews who accompanied the Budiner or “Shepherd Scythians” to the Swedish islands around

400 bce, in an exodus said to have been driven by the Macedonians.

By the Middle Ages, werewolves became no less accepted in the European worldview. They were seen as a threat to established

order, and they were often described as sorcerers and heretics. “An accursed college,” Swedish Catholic ecclesiastic

Olaus Magnus called them in the 16th century, “desirous of innovations contrary to the divine law.”

Werewolves, it turns out, have ancient kinship with vampires, and sometimes the legends overlap. In medieval Eastern Europe,

particularly during the “plague centuries” (1300–1700), the bodies of persons executed for being werewolves

were often cremated to prevent them from returning as vampires. In Hungary, Slovenia, Serbia and Bulgaria, the vampire has been

linked to the werewolf, and in Serbia, the werewolf and vampire are known collectively as a single creature, the vukodlak.

Victorian folklorist Sabine Baring-Gould highlights this close relationship, too, and in so doing leads us toward

more ancient ghouls. Baring-Gould describes a French historian’s account: “Marcassus relates that after a

long war in Syria, during the night, troops of lamias, female evil spirits, appeared upon the field of battle,

unearthing the hastily buried bodies of the soldiers, and devouring the flesh off their bones. They were pursued and

fired upon, and some young men succeeded in killing a considerable number; but during the day they had all of them the

forms of wolves or hyenas.” Baring-Gould felt there was “a foundation of truth in these horrible stories.”

The devouring of human flesh is a particularly ghoul-like characteristic, as we shall soon see.

|

|

|

|

alfredo dagli orti / art archive / art resource |

|

interfoto / alamy |

|

A history of Scandinavia dated 1555 depicts a “metamorphosis of men into wolves,” left, and an inset from

the Hereford mappa mundi in the 13th century, right, shows dog-headed men. |

The Arabs, too, have a werewolf in their folklore: the qutrub. The word is a corruption of the Greek

lykanthropos, or wolf-man. Edward Lane, a translator of the One Thousand and One Nights, says the male

ghoul is called by this name. In popular belief, the qutrub is either a man or a woman who is transformed into a

wolf-like beast by night and who feeds upon corpses, but it is not a wolf per se.

Qutrub was furthermore the Arabic term for lycanthropy. In the early 10th century, in his classic medical

encyclopedia Liber Continens (Al-Hawi al-Kabir, often called The Virtuous Life in English),

physician Abu Bakr Muhammad Al-Razi followed the tradition of Paul of Aegina and other classical authors, describing

lycanthropy as a brain disorder or a psychosis rather than a physical transformation. He saw it as a kind of madness

that compels a person to behave like a wolf. To treat the ailment, he prescribed opium to induce sleep, and baths and

topicals to “humidify” the brain.

The classic zombie is a corpse revived by a sorcerer or magician, usually in the context of Haitian, Louisianan or

West African Voodoo. The zombie then becomes entirely subject to the power of its master. In literature, zombies have

been known to guard treasure, terrorize neighborhoods and, more generally, commit murder. The term “zombie”

was popularized in the United States in 1929 in The Magic Island, a book about Haitian Voodoo by reporter and

occultist William Seabrook.

In the 1980’s, Harvard ethnobotanist Wade Davis asserted a pharmacological basis for the Voodoo-based zombie

of Haiti. He claimed that if two toxic substances entered the bloodstream simultaneously—pufferfish powder and a

dissociative drug like datura—the effect could be a deathlike state in which the victim’s will would be subject

to that of the Voodoo sorcerer. Other scientists, however, called this “overly credulous.”

It is important to note at this point that the classic Voodoo zombie is not one able to turn others into zombies,

nor is it an eater of human flesh.

The modern articulation of the zombie, so popular today in tv shows, movies and

video games, is thus quite a different creature. This new zombie, popularized in director George A. Romero’s

1968 cult-classic movie, “Night of the Living Dead,” is a revived corpse that relishes human flesh and,

of that, the brain most especially. This zombie’s condition is caused originally by an outside agent—a

virus from space, atomic radiation, mutagenic gas or other uniquely 20th-century malady—and from there it can

usually be transmitted to living humans with a simple chomp of the fangs. In zombie tales of the early 21st

century—film, video, print or computer game—the undead contagion spreads virally worldwide, bringing on

a “zombie apocalypse.” Yet all is not lost, because to overcome today’s zombie, beheading or

violent destruction of its brain usually suffices.

|

This new zombie is proving vastly more popular—and lucrative to its entertainment-media sorcerers—than

even its most monstrous rivals. A recent Google search showed the word “zombie” garnering 318 million

Web pages, while “vampire” collected a mere 80 million, with “werewolf” loping in third at

44.5 million.

The zombiemania has reached the point where even a serious institution such as the us

Centers for Disease Control (cdc) has taken advantage of the pop-culture phenomenon

to promote emergency preparedness. The cdc’s Atlanta headquarters plays a role

in the first season of the tv series “The Walking Dead,” and last year, the cdc

posted a real article on its blog called “Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse” that told readers how to

prepare for a fictional zombie invasion and, in the process, “maybe … even learn a thing or two about how

to prepare for a real emergency.”

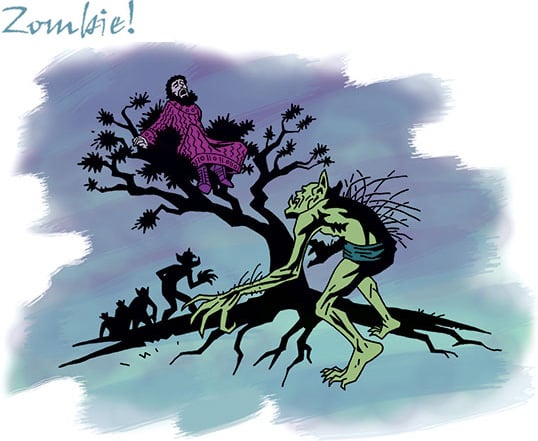

Curiously, when he filmed “Night of the Living Dead,” George Romero says he did not have zombies in

mind at all. His creatures were envisioned as ghouls, he has recalled in interviews, the flesh-eating creatures of

Arabian lore. His undead attackers are even called that in the film. But somehow the word “zombie” was

the one that caught on, and before long, Romero himself was using it, including in the dialogue of his 1978 sequel

“Dawn of the Dead.” (He went on to make four more zombie movies. Controversial in its day, in part for

its graphic violence, “Night of the Living Dead” was recently selected by the us

Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry as a work of “cultural, historical or aesthetic

significance”—lest it die an untimely death.

It is this ghoul-zombie that has the long history, and, like the werewolf, it goes back to the Epic of Gilgamesh

and the king’s tensions with the goddess Ishtar, who thus describes her passage down to the underworld:

If thou openest not the gate to let me enter,

I will break the door, I will wrench the lock,

I will smash the door-posts, I will force the doors.

I will bring up the dead to eat the living.

And the dead will outnumber the living.

Horror novelist Jonathan Maberry has pointed out that, in “Dawn of the Dead,” Romero in fact echoed

Ishtar with the line: “When there is no more room in Hell, the dead will walk the earth.”

|

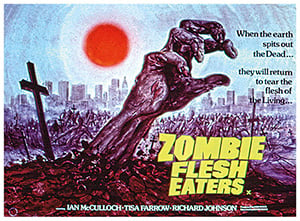

interfoto / alamy; moviestore collection ltd / alamy (detail) |

|

|

Top: Though not risen from the dead, cannibals appear in the Hereford mappa mundi. Above: In 1979,

a movie poster entices viewers with a distant echo of the portentous words Ishtar spoke to Gilgamesh.

|

Ghouls of the Arabian tradition—distinct from those Ishtar describes—are normally neither revenants

or revived corpses, but rather an extreme form of another living species: the jinn, which in English became “genie.”

The jinn, shape-shifters with various extra-human powers, are often associated with magic and sorcery. But Arabian

belief includes both good and bad jinn. Ghouls are obviously the bad sort, and though most times they view people as

menu items, they occasionally prove allies—hardly a trait we expect in any modern movie zombie.

Many ghouls are portrayed in Arab lore as lurking in caves in remote deserts, waiting to snare and devour innocent

travelers who may be passing by. The female ghoul, or ghulah, is very popular in folktales; she sometimes

shape-shifts into a beautiful woman who marries an unsuspecting man and has children by him.

Matthias de Giraldo and M. Fornari, in their 1846 Histoire des Sorciers (History of Sorcerers), tell

of a legend about a ghoul in 15th-century Iraq: A Baghdad merchant’s son married a beautiful young woman

against the advice of his father. The young man soon discovered his bride was making mysterious nocturnal visits

to a nearby cemetery. One night, he secretly followed her into a mausoleum, where he found to his horror a party of

ghouls assembled with the spoils of graves they had violated, feasting on the flesh of long-buried corpses. Among

them was his own wife, and this explained why, at home, she never touched her supper. The next day, the husband

confronted her and, vampire-like, she tried to open his jugular vein to drink his blood, but he succeeded in throwing

her down and, with a single blow, killing her. She was buried next day, but three days later, at midnight, she

reappeared, attacked her husband again and once more attempted to suck his blood. This time he fled, and the following

day he found her in her tomb, where he cremated her body, cast the ashes into the Tigris River and was free of her.

Such imaginative tales and romances from and about the Middle East, dating back to the Middle Ages and beyond,

have often featured ghouls as grave-violators. Says Baring-Gould:

Of a moonlight night weird forms are seen stealing among the tombs, and burrowing into

them with their long nails, desiring to reach the bodies of the dead ere the first streak of dawn compels them to

retire. These ghouls, as they are called, are supposed generally to require the flesh of the dead for incantations or

magical compositions, but very often they are actuated by the sole desire of rending the sleeping corpse, and disturbing

its repose.

Not all ghouls disguise their hideous countenance. Palestinian–American folklorist Inea Bushnaq describes

ghouls as the wildest and most repulsive-looking of the jinn, hairy, filthy and long of tooth with a sharp nose for

the scent of human flesh. Unlike most of the eerily mute modern zombies, these ghouls talk: In the tales, they have

a set entrance speech, which comes as the human hero stammers his “salamu alaikum” (“peace

be with you”):

Lawla salaamak

Sabaq kalaamak

Had not your greeting

Come first before your speaking,

I would have torn your muscles each from each

And used your bones to pick my teeth.

Here is another vivid ghoul, this time from a Yemeni folk epic about sixth-century Himyarite King Sayf ben Dhi

Yazan. Most unregally, he is treed by approaching ghouls. The monsters are closing in:

And as he gazed, he saw an old man approaching … hideous of countenance, his face round as a shield,

his jaws and nose as great as a buffalo’s, with fangs jutting out like pincers, and his ears as large as catapults;

he had nails like daggers, the hair on his body was like the spines of the porcupine, and his eyes were like slits of

red flame. Hideous and evil-smelling he was, his face smoldering with evil….

This is not exactly the shambling, blood-smeared, undead corpse of the modern zombie movie, but the effect is close

enough. Interestingly, as the story unfolds, the no-less-hideous Queen of the Ghouls arrives, but she displays a

rare sympathy and helps the king escape an impending ghoul apocalypse caused by her own people.

So we see that, throughout the imaginative visions of vampires, werewolves and zombies that haunt western pop and

literary culture, there are deep echoes that reverberate all the way back to the earliest Mesopotamian civilizations.

Up they came through those ages, into Arabia, Greece and Europe, vampires blending and morphing into werewolves,

werewolves into zombies and so on in endless combinations—yet all three hark back no less to the oldest Arabian

ghouls. While they have walked among the nightmares of far too many lands to claim purity in their Middle Eastern origins,

it’s nice—and perhaps prudent—to better know their lineage. Facts can be handy defenses, armor for

the mind, when next sitting in a dark theater, gripping the armrests, about to be horrified.

|

Robert Lebling (lebling@yahoo.com) is a writer/editor and communications specialist. He is author of Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar. |

|

June Brigman (www.artwanted.com/juneart) has worked for Marvel and DC Comics, as well as National Geographic World magazine. For 15 years, she was the artist for "Brenda Starr, Reporter," a nationally syndicated comic strip. She currently works as a character designer for Teshkeel Comics on the "The 99" comic book series. |