|

|

| De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Art Library (Detail) |

| Top: Resembling polo players depicted both in 18th-century India (above) and in 15th-century Iran (below), two contenders face off on a grass pitch during the competition for the 2013 Dubai Polo Gold Cup. Polo came to the West in the 19th century with British colonial troops, who found it popular in northwestern India. |

|

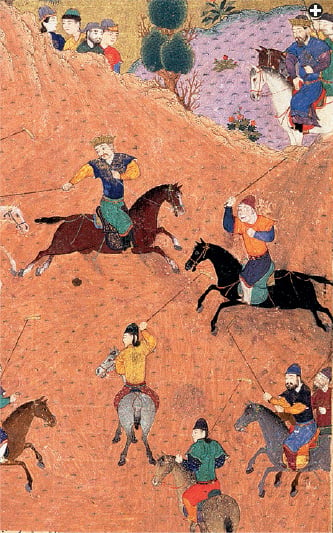

| Royal Asiatic Society / Bridgeman Art Library |

| The oldest record of polo comes from an Iranian account dating near 600 bce. That is some 2000 years before this miniature, left, was painted in the 1440’s for the Shahnama of Firdowsi. It shows the legendary character Gushtap playing polo against Caesar in one of several allegorical sporting contests. |

balmy March wind blows off the Arabian Gulf and ripples through palms framing the verdant playing field of the Dubai Polo & Equestrian Club. On the far side of this smooth rectangle of grass, glossy black Aston-Martins and gleaming white Bentleys park, while American-style cheerleaders flounce to the beat of a Michael Jackson song. Men in crisp, pressed thobes and mirrored shades mingle with ladies teetering on high heels and families sitting down to picnic lunches. Around me I hear a mélange of English, Spanish and Arabic; behind me, in the corrals, the ponies whinny and stamp.

balmy March wind blows off the Arabian Gulf and ripples through palms framing the verdant playing field of the Dubai Polo & Equestrian Club. On the far side of this smooth rectangle of grass, glossy black Aston-Martins and gleaming white Bentleys park, while American-style cheerleaders flounce to the beat of a Michael Jackson song. Men in crisp, pressed thobes and mirrored shades mingle with ladies teetering on high heels and families sitting down to picnic lunches. Around me I hear a mélange of English, Spanish and Arabic; behind me, in the corrals, the ponies whinny and stamp.

Then there’s a rumble of hooves as the match gets under way, followed by the sharp thwack of a wooden mallet as it strikes the ball. After a few hard-riding minutes, the first chukka is over and the horses canter off the pitch, snorting, pumped up and foaming with sweat. After a quick change of mount, the players, dazzling in pristine white jeans and polo shirts in primary colors, are off again. Even if, like me, you don’t quite understand the rules of the game, it’s a truly exciting spectacle.

The typical polo match comprises at least four chukkas of seven minutes, and each of the four players on the two sides will need a fresh horse for every chukka. But this is no average match: This is the 2013 Dubai Gold Cup, a major event on the global polo calendar since its inception in the United Arab Emirates in 2010. As businessman Amr Zedan tells me—he is both patron of and player on the Zedan Polo Team competing here today—“Back in 2010 there was barely an event here. Now the Dubai Gold Cup really puts the uae on the polo map.” As elsewhere across the globe, polo is primarily a pro-amateur sport here, with each of the teams supported by wealthy amateur players who pay their professional teammates, and the tournaments are heavily sponsored.

International polo tournaments may be a fairly recent uae import, but it is in present-day Iran, only 200 kilometers (125 mi) away across the Strait of Hormuz, that the game is thought to have been invented at least 2500 years ago. The prevailing theory has it that polo, or chogân, as it is known in Farsi, originated among the Aryan (Iranian) tribes of Central Asia, with the first recorded public match taking place around 600 bce, when the Persians took on the Turkomans and lost. And certainly it’s in Persian art and literature that we find the most evocative accounts of polo dating from this period and on to its heyday in the Middle Ages.

In his epic Shahnama (Book of Kings), the 10th-century poet Abul-Qasim Firdowsi gives several descriptions of polo; in each case the game is cited to demonstrate the horsemanship and valor of the player. Firdowsi’s near contemporary, Mantiqi Razi, wrote these lines, quoted by George Morrison in his History of Persian Literature:

Is the moon ill perhaps tonight?

She looks so thin that she could cry.

A silver shield before, but now

A polo-stick across the sky....

A century later, also according to Morrison, the Qabusnama, written by an amir of the Ziyarid dynasty for his son Gilanshah, offers advice on such weighty matters as “eating, drinking, playing polo, buying slaves, medicine, poetry, generalship, love, marriage, musicianship and many more.” But perhaps the most famous Persian writer on polo, as on other more profound subjects, was the 11th- and 12th-century poet, astronomer and mathematician Omar Khayyam, whose Rubaiyat contains a verse rendered like this in Edward FitzGerald’s classic 19th-century translation, written before polo was familiar in England:

The Ball no Question makes of Ayes and Noes,

But Right or Left, as strikes the Player, goes;

And He that toss’d Thee down into the Field,

He knows about it all—He knows—HE knows!

and like this in a modern rendition:

In the cosmic game of polo you are the ball.

The mallet’s left and right becomes your call.

He who causes your movements, your rise and fall,

He is the one, the only one, who knows it all.

|

|

Above: Polo tires horses quickly, and advantage in the game can go to those who field enough mounts to change horses frequently between each match’s four or more seven-minute periods, called chukkas.

Lower: Players for the Abu Dhabi team get ready for a match. many top polo players today hail from argentina, where the British introduced the sport in the late 19th century. “at that time, we had a lot of gauchos in argentina,” says Hugo Barabucci of the Ghantoot Racing & Polo Club. “We are born with horses.” |

For these Persian poets, polo is evidently more than just a game—it’s an allegory for life itself. And it’s not only in literature that such charming depictions of the sport are found. Many of the world’s great libraries proudly display illustrated Persian manuscripts, and many of the miniatures show polo matches, some with royal participants and riveted spectators.

If, as it appears, polo had evolved into the sophisticated “game of kings” by the time it was patronized by the sovereigns of the Parthian Empire (247 bce–244 ce), how did this apparently captivating arrangement of horse, mallet and ball start out? Dr. Abdelrahman Abbar, a lawyer and polo enthusiast from Saudi Arabia who has played with England’s Prince Charles and has read widely on the subject, thinks he has an answer—and it’s a pretty gruesome one. “Originally, when warriors from the Central Asian steppes went into battle, killing the enemy’s general meant you had won. There were no phones or Internet then, so they took the general’s head and put it on a spike to show it off to the losing army. They would relay it on these spikes, and pick it up with the spikes when they dropped it. In peacetime, they practiced with the head of a goat or sheep.”

It was in Gilgit, capital of present-day northern Baltistan, in the foothills of the Karakoram Mountains, that this brutally triumphal act of war evolved into something closer to the gentlemanly game we know today, continues Dr Abbar. “They had an area of land there, measuring around 150 meters by 100 meters (500' x 325'), and this became the pitch, the playing field. They would play a game with the head of a sheep or goat whereby whoever ended up with the head was the winner.” The pitch Dr. Abbar refers to may even be the one near which is a plaque with the famous inscription, “Let other people play at other things. The king of games is still the game of kings.” Polo is still played there to this day.

|

| A post-game shower helps keep horses healthy in Dubai’s warm climate. |

John Horswell is coach of the Habtoor Polo Team, also competing in the 2013 Dubai Gold Cup, and while he agrees about the birthplace of the game, he tells a slightly different version of the story. “Whether it was Chinese, Mongolian or Persian, the game came out of that region of the world,” he says. “The oldest prints on polo show Mongolian women playing polo with enemies’ heads. The men were out at war, so to keep the women amused, they used to throw them the odd head.”

Whether the heads used for polo were those of goats or generals, it’s apparent that the sport’s foundations are mercifully shrouded in the mists of time, and modern theories amount to little more than a blend of fact and fiction. Likewise, whether polo’s birthplace was Persia or Pakistan, China or Tibet, Mongolia or Manipur, depends largely on whom you ask. In truth, it seems most likely that polo was a folk game that developed more or less concurrently in different regions of Central Asia, with local variations in “rules”—a loose term in this context. In some areas a headless goat carcass was used instead of a head, a distinction that then developed into the fast and furious game of buzkashi—still played today in some areas of Central Asia.

What isn’t in doubt is the game’s rapid expansion, courtesy of the Mughal conquerors, across Central Asia as far as the Indian subcontinent where, by the 16th century, the Emperor Babur—himself an expert player—had established the game as a royal pastime. There’s some evidence it had reached India even earlier: The Imperial Gazetteer of India, published in 1881 by Sir William Wilson Hunter, records the death of Sultan Qutb-ud-Din Aibak in 1206 when his pony fell during a polo match.

By the seventh century, the game had spread along the Silk Roads to Japan from China, where a polo stick appeared on the royal coat of arms. It was in 10th-century China that the Emperor T’ai-Tsu, after a relative fell and died during a polo match, reputedly ordered the beheading of all the remaining players. In the other geographical direction, the game’s popularity stretched as far west as Egypt, where Harun-al-Rashid was the first of the Abbasid caliphs to play the game, and to Byzantium, which saw the first recorded royal polo fatality in the late ninth century, when the Emperor Alexander supposedly died from exhaustion after a particularly arduous match.

|

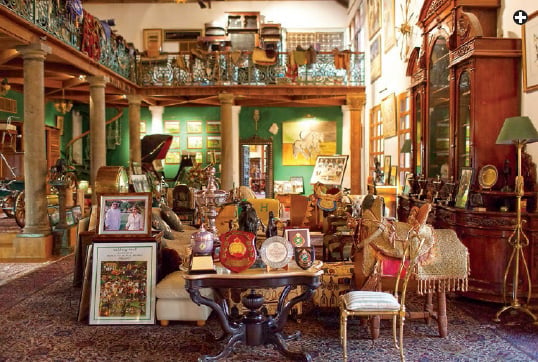

| Polo memorabilia fills a museum-like hall at the Desert Palm Polo Club, founded by investor and polo enthusiast Ali Al-Bwardy. |

Yet despite Crusader armies trampling all over the Levant between the 11th and 13th centuries, polo didn’t reach Europe until six centuries later, when the British discovered the game in northeastern India. Nicholas Colquhoun-Denvers, chairman of England’s venerable Ham Polo Club in Richmond, Surrey, takes up the story. “The game was played in Persia in antiquity, but modern polo originates in Manipur, near Burma,” he says. “And this was thanks to a gentleman we call ‘the godfather of polo,’ Major General Joe Shearer, the assistant administrator in the region for the British government. In his dispatches he mentioned a game they played there called sagol kangjei, and around 1860 a reporter from The Field magazine wrote an article about it. Some British army officers stationed in Aldershot, Hampshire, read this, took some walking sticks and a billiard ball, mounted their chargers and tried it out. In those days most of the army was mounted, and they decided this was a great way to train the cavalry officers. Then, some 10 years later, the Hurlingham Rules were created, which we still use today. Polo is a great sporting success story for Britain, which exported it to perhaps 77 other countries around the world.”

Including, of course, its most famous home, Argentina, by which time the game was known by an Anglicized form of the Indian name for the wooden ball, pulu. In contrast to polo’s foggy ancient origins, most experts agree on how this modern spread happened.

|

| Spectators watch from the shade of a tent at the Dubai Polo & Equestrian Club. Modern polo is played with four players to a team, and the rules of play are enforced by an umpire on the field. |

In Dubai’s neighboring emirate, Abu Dhabi, is the Ghantoot Racing & Polo Club, which covers some 300 hectares (740 acres), its seven velvety-green pitches vibrant against the stark desert backdrop. Inside the clubhouse, all leather armchairs and wood paneling, I meet Hugo Barabucci, 45, an Argentinian polo player who has adopted this club and this country as his home. Over a cup of Arab coffee, he fills me in. “We’ve been playing polo in Argentina for more than 100 years, since the English came over to buy land and farm there. At that time we had a lot of gauchos in Argentina, from the pampas, and as we are born with horses it was not a difficult sport to pick up. This is why, in my opinion, we have the best polo players in the world. It’s part of our culture.”

Marco Focaccia, 35, polo manager at the Dubai Polo & Equestrian Club—the host of the 2013 Gold Cup—is another Argentinian who has relocated to the uae. He echoes Barabucci’s thoughts on how polo grew to be so popular in his homeland, adding, “When the English came to Argentina in the 19th century, they brought their own thoroughbred horses with them to play the sport. Argentina is flat and ideal for the game, as you can improvise a polo field anywhere. Then, when the English thoroughbreds mixed with the Argentinian ponies, that helped improve the game further.”

So, it seems, the key to this long-running global saga lies with the horse. And perhaps the horse is also the reason polo has returned, full circle, to the part of the world where it began at least 2500 years ago. Santiago Torreguitar, polo manager at the Santa María Polo Club in Sotogrande, Spain, and series director of the Dubai Gold Cup, thinks so. “There is a culture of horses here, similar to Argentina. And this is a nice country to hold tournaments—you have the weather here, and money. Anything to do with horses requires some money.”

But polo in the uae is a fairly recent phenomenon. It is businessman Humaid bin Drai who is generally credited with bringing polo here in 1974, when he established the Dubai Polo Club near al-Awir. And although he himself never played, all four of his sons do. The eldest, Saeed bin Drai, is now patron of the Bin Drai polo team, the first all-family squad in a sport still dominated by Argentinians, who make up three out of every four players in the uae.

One of the native Emirati players is Nasser Mohammed Saif al-Dhaeri, 38, of the Ghantoot Racing & Polo Club. “I’ve been playing since 1997,” he tells me. “I rode horses when I was a boy growing up on our farm. Shaykh Falah [bin Zayed Al Nayhan, brother of the president of the uae] saw me and asked me to join his team. He sent me to London to learn to play, at Ham Polo Club, with the teacher Tim Healey.” Al-Dhaeri has also learned much from the Argentinians he’s played with—and against—in his years as a top competitor. “When they play polo in Argentina, they play from the heart, and there are so many good players that it’s hard even to touch the ball!” he adds.

For the players, at least, Argentina and the uae seem a polo match made in heaven. But does the world-renowned Arabian horse fit into this latest chapter of the story? Dr Abdelrahman Abbar again provides enlightenment. “It’s true that Arabian horses have certain qualities—beauty, intelligence, endurance—and were famous as warhorses. But they are not suitable for the game of polo, which is more confined than the battlefield.”

So today’s “Emirati” polo ponies are mostly thoroughbreds—Anglo-Arabian fusions—imported from Argentina and valued chiefly for their speed, says Dr. Abbar. Hugo Barabucci agrees that the pure Arabian horse is unsuited to polo. “We tried many times to use pure Arabian horses, but they are too sensitive for polo, and not as strong as Argentinian ponies. So we are now breeding Argentinian horses here, too.”

One downside to polo in the uae compared to Argentina, the uk or the us—the current top three polo-playing nations—Barabucci continues, is the expense of keeping horses, mostly due to the nature of the terrain. “In Argentina it’s cheap to keep horses. The terrain’s flat and the weather’s good,” explains Amr Zedan of the Zedan Polo Team. “And in both the uk and Argentina, there’s natural greenery that the horses can graze off-season, but here you have to keep them stabled, which is expensive. It can cost $1000 per month to keep a horse in the uae, whether it’s playing or not.” That cost is multiplied for elite players, who replace their fatigued mounts after every chukka and need a number of ponies to compete at the top level.

Despite the difficulties of the terrain, and the expense of the game here, polo’s evidently a sport that’s becoming increasingly popular—and not only with men. One notable female player is Shaykha Maitha bint Mohammed al-Maktoum, daughter of the prime minister of the uae, a keen polo player who won the 2013 Cartier International Dubai Polo Challenge with her team, competing alongside the men. Faris Al Yebhouni, patron and captain of the Abu Dhabi Polo Team, is not surprised the game is taking off in the uae. Between practice chukkas, he explains why. “There are various reasons: The country’s very famous for the horse industry—racing, show-jumping, dressage—but polo gives you the additional excitement, the adrenalin charge. Polo is like a drug,” he argues. “And it’s a small world—you know everyone. With the increasing investment over the past few years, polo has a great future here.”

|

| Good cheer, fellowship and a handsome trophy are the rewards for 2013 champions Ghantoot Racing & Polo Club of Abu Dhabi. |

Timur Tezişler, who sits on the 2013 Dubai Gold Cup committee, agrees. “The thing about polo is that it’s a really exciting sport. Anyone who comes along here can enjoy a decent game. In this respect it’s totally different from horse racing, where you have to know lots about the horse and the form to really appreciate it.” As I discover myself, as I watch the final match of the Gold Cup back at the Dubai Polo & Equestrian Club, where Ghantoot and Habtoor are battling it out for the champion’s trophy. A horn blows to signal the end of the match, with the final score Ghantoot 14, Habtoor 6.

The sun is setting as the podium is prepared for the prize-giving, and long shadows thrown by the surrounding palms stretch across the now silent pitch. There’s no prize money at stake here: The tournament, hosted by the Al-Habtoor family, is held purely for sport, doubtless combined with the satisfaction of trouncing one’s rivals.

First the three runner-up teams come up to receive their prizes, the shaykhs in their shades, the players in their now-grubby white jeans. Even the best-playing pony wins a prize, looking rather overwhelmed as he comes up to receive it. Then, finally the winning team climbs the podium to a roar from the crowd and a lightning storm of flash bulbs. There may not be Champagne to spray over everyone, but that doesn’t seem to dampen anyone’s spirits this warm March evening.

|

Historian and travel writer Gail Simmons (www.travelscribe.co.uk) surveyed historic buildings and led hikes in Italy and the Middle East before becoming a full-time travel writer for UK and international publications. She holds a master’s degree in medieval history from the University of York and is currently earning her Ph.D. She lives in Oxford, England. |

|

Celia Peterson (www.celiapeterson.com) has lived in Dubai for 10 years as a portrait, editorial and lifestyle photographer, and she recently expanded into filmmaking. Her favorite subjects are “compelling either for their quirkiness or because they highlight positive human stories.” |

www.poloclubdubai.com

www.dubaipologoldcup.com |