|

| Performing in Berkeley on March 2, Voices of Afghanistan is, from left to right, Abbos Kossimov, Pervez Sakhi, Homayoun Sakhi, Ustad Farida Mahwash, Khalil Ragheb and Ezmarai Aref. |

ince 1980, the San Francisco Bay Area has become home to the largest community of Afghan expatriates in the United States—some 120,000—most of them living in the East Bay community of Fremont. Tucked away in that tight immigrant enclave are some of the greatest exponents of Afghanistan’s war-shattered art-music tradition. The principals in this group, legendary vocalist Ustad Farida Mahwash and Homayoun Sakhi, the young master of the double-chambered rubâb lute, enjoy iconic status among Afghans.

ince 1980, the San Francisco Bay Area has become home to the largest community of Afghan expatriates in the United States—some 120,000—most of them living in the East Bay community of Fremont. Tucked away in that tight immigrant enclave are some of the greatest exponents of Afghanistan’s war-shattered art-music tradition. The principals in this group, legendary vocalist Ustad Farida Mahwash and Homayoun Sakhi, the young master of the double-chambered rubâb lute, enjoy iconic status among Afghans.

No surprise then that a large number of Bay Area Afghans have made their way through the unfamiliar maze of the Berkeley campus to attend the concert. The rest of the house consists mostly of uninitiated, culturally curious listeners. The Afghans witness a summit of star power rarely seen at their intra-community concerts, while the newcomers experience an irresistible seduction by the passion and virtuosity of Afghan music. That allure, and the confluence of these communities, goes to the heart of the group’s mission: to give Americans a vision their country that is—to borrow a Berkeley phrase—based on love, not war.

has just finished the most ambitious modern recording of Afghan music available today, Love Songs for Humanity (World Harmony Productions). Its nine vocal and three instrumental tracks cover the ensemble’s full range of folkloric and classical music. Featuring the percussive, plucked string melodies of the Afghan rubab, rolling hand-percussion rhythms has just finished the most ambitious modern recording of Afghan music available today, Love Songs for Humanity (World Harmony Productions). Its nine vocal and three instrumental tracks cover the ensemble’s full range of folkloric and classical music. Featuring the percussive, plucked string melodies of the Afghan rubab, rolling hand-percussion rhythms and soulfully mellifluous vocals, notably from the legendary Radio Kabul singer Ustad Farida Mahwash, this recording also augments the core, five-piece ensemble with well-chosen guests. A soaring rendition of Jalaladdin Rumi’s poem “Deedam Negar-i Khud- ra” opens the album with verses of extravagant praise for a player of the rubab: “His sparkling plectrum set ablaze all hearts with blissful chants in rapturous ecstasy”—Rumi could just as well have been talking about the group’s own Homayun Sakhi, whose masterful rubab playing does just that throughout this recording. Mahwash’s iconic voice finds an unexpected complement on the album’s mesmerizing lead track when joined with the also iconic voice of African diva Angelique Kidjo. Here and on other tracks, there is robust string support from the Clinton Quartet, and guest violinist Layth Al Rubaye adds depth and texture. and soulfully mellifluous vocals, notably from the legendary Radio Kabul singer Ustad Farida Mahwash, this recording also augments the core, five-piece ensemble with well-chosen guests. A soaring rendition of Jalaladdin Rumi’s poem “Deedam Negar-i Khud- ra” opens the album with verses of extravagant praise for a player of the rubab: “His sparkling plectrum set ablaze all hearts with blissful chants in rapturous ecstasy”—Rumi could just as well have been talking about the group’s own Homayun Sakhi, whose masterful rubab playing does just that throughout this recording. Mahwash’s iconic voice finds an unexpected complement on the album’s mesmerizing lead track when joined with the also iconic voice of African diva Angelique Kidjo. Here and on other tracks, there is robust string support from the Clinton Quartet, and guest violinist Layth Al Rubaye adds depth and texture.

Visit www.voicesofafghanistan.com for more information.

CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO SONG SELECTIONS FROM THE ALBUM.

|

“I am a messenger of love,” says Mahwash with definitive simplicity. “Art generally, and singing especially: It’s all love.” Romantic classical songs, or ghazals, are Mahwash’s specialty, and they dwell feverishly on the joy, frustration and heartbreak of people in love. Hearing her clear, supple voice tracing those wistfully meandering melodies, and seeing shadows of ephemeral emotion cross her transparent, world-weary face, you understand this right away; no translation of the songs’ mostly Dari and Pashto lyrics is really needed. At 66 and elegantly attired, a jewel-studded heart of gold on the side of her nose, her black hair in a tight bun above her head, Mahwash cuts a figure of modest, matronly grace. But that liquid voice, gilded by classical ornamentation here, a hint of a rasp there, still conveys the urgency of a young girl eagerly embarking on a journey to fulfillment.

On stage, Mahwash is flanked by five instrumentalists. To her right, brothers Homayoun and Pervez Sakhi, on rubâb and tula (flute) respectively, sit cross-legged side by side. Homayoun Sakhi, the group’s musical director, is young enough to be Mahwash’s son. Trained in both classical and folkloric traditions by his music-master father, Ustad Ghulam Sakhi, he was a natural musician from childhood. Not satisfied with the limitations of his 2000-year-old instrument, he added melody strings to extend the rubâb’s melodic range and developed original picking techniques that diversify its sonic possibilities—from the spitfire, percussive staccato of a banjo to the jangling overtones of a santoor hammered dulcimer. Sakhi also plays tabla (hand drums) and harmonium and sings beautifully, sometimes adding his velvet tenor to complement Mahwash’s lovesick alto.

To Mahwash’s left, on harmonium, sits Khalil Ragheb. His good looks—think a middle-aged Paul McCartney—belie his 16 years as a television presenter in Iran, a career he has revived during his 23 years in the Bay Area. Ragheb first played with Mahwash in 1977, when he was working with another iconic Afghan singer, Ahmad Zahir, who died in his prime in June 1979, when the country was in political turmoil. That event helped drive Ragheb into exile, more than a decade before Mahwash herself. So their reunion in this group has a depth of nostalgia that you feel in their ceremonious interactions.

|

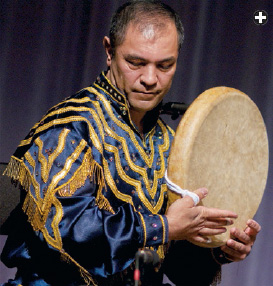

| Capable of unleashing “feral virtuosity,” percussionist Kossimov mixes Afghan and Uzbek sounds with those of India, West Africa and jazz. His principal instrument is the doyra. |

Bookending the ensemble are the two percussionists, tabla player Ezmarai Aref and doyra, daff and derbouka virtuoso Abbos Kossimov. Kossimov is Uzbek, the only non-Afghan in the group, but his broad knowledge of Central Asian music more than qualifies him in this company. Furthermore, like Homayoun Sakhi, he is a phenomenon—a ferocious performer and brilliant innovator.

Kossimov’s principal instrument, the doyra, is a small frame drum lined with a curtain of 64 metal rings that can jingle together or slap against the inner wall of the instrument’s dried-skin face. However, he has extended its possibilities in every way imaginable, borrowing techniques, strokes and rhythms from Indian tabla, West African djembe and even jazz drummers. Today he has students around the world and tours with a variety of world-class artists, including Indian percussion colossus Zakir Hussain.

At one point in the Voices of Afghanistan program, the group departs from romantic ghazals and Afghan folk songs, and Hou-mayoun Sakhi—accompanied by the two percussionists—plays a demanding classical raga. Ragas call on a player’s deep knowledge of melodic ornamentation, rhythmic structure and improvisational skill. Beginning slowly and alone, he explores the sonic possibilities of his instrument with deft slides and melodic flourishes. The rubâb is the ancestor of the sarod, one of the most popular instruments in North Indian classical music. But as this long piece unfolds, Sakhi displays unusual trademark techniques, such as striking the rubâb’s 15 sympathetic, or resonating, strings with his fingernails to produce chiming cascades of cyclic melody.

In the Berkeley concert, Homayoun engages in near-telepathic exchanges with the percussionists, particularly Kossimov. The two seem to share one mind as they shadow each other’s tricky improvised rhythms perfectly. Near the end of the raga, Kossimov cuts loose with a display of feral virtuosity. Teeth set and eyes gleaming, his fingers fly like mechanized hammers, and out of a torrent of beats a few announce themselves with the force of rifle shots. He plays two doyras at once, tosses one in the air and catches it within context of his phrase, and—in an almost carnivalesque flourish—spins his doyra on his finger like a dinner plate. The crowd rises with a collective roar of approval. Afterward, Kossimov, Homayoun and Aref come together again in a jaunty reiteration of the raga’s main theme, releasing the pressure, rocking with physical ease and smiling at one another like brothers in on a family joke.

|

| Originally a European musical invention, the hand-pumped organ known as the harmonium that Ragheb uses in Voices of Afghanistan has been part of classical ensembles in India and parts of Central Asia since the late 19th century. |

The group then eases into one of Mahwash’s slowest and deepest ghazals, “Ishq Mami Biya” (You Are My Love and Soul). Mahwash’s voice, absent for a time, returns like a fresh breeze, the occasional break in it like a flaw in a diamond. The performance ends in a sustained standing ovation, an encore and another ovation. For Voices of Afghanistan, the intersecting worlds have joined; the group’s mission has been magnificently fulfilled.

Of course, none of this has come easily. Dawn Elder, who created this group with Mawash and Homayoun, has made a career of bringing music from many corners of the world to international recognition. “Sharing music is the greatest gift one person can give to another,” she told me after two years of hard work on the project. “Voices of Afghanistan are an inspiration to me. They bring together incredible talent, a humble nature and a deep love for their country and culture. The world needs to hear this music.”

For the musicians, the hard work began many years earlier, when they chose to brave the stigma of pursuing an artistic career in a conservative and politically unstable society. Each of the Afghan members of Voices of Afghanistan followed his or her own path from Kabul to Peshawar, Pakistan—the destination for Afghan musicians driven from the capital by the many outbreaks of war since the Russian incursion of 1979—and ultimately California, the place they all now call home. But it was not until 2012, at Elder’s urging, that they came together as a formal group.

None of these musicians’ journeys has been more storied, or harrowing, than Mahwash’s. Today she lives with her husband, Farouq Naqshbandi, in a small house just off Fremont Boulevard. In the days before the Berkeley concert, they welcomed Elder and me into a home festooned with framed awards, posters and photographs with famous people—including Mahwash’s musical masters and her personal favorite, the late South African singer Miriam Makeba.

|

| Far older are the hand drums called tablas and the stringed rubâb, which Homayoun Sakhi was taught to play by his master-musician father. |

There were cases crowded with figurines of flowers, whirling dervishes, women singing and other whimsical fare. To tour Mahwash’s salon and dining room was to relive a career that spans four decades and five continents. As we sat down with green tea, almonds and sweets, she returned to the beginning—the home in Kabul where she grew up listening to her mother recite the Qur’an and instinctively singing every beautiful melody she heard.

“My mother had a good voice,” Mahwash recalled. “I have this voice from her.” Just the same, the person most responsible for Mahwash’s successful career might actually be her husband, whose support has been courageous and unflagging. It’s also somewhat surprising, considering the couple’s beginnings. “Our marriage was not a love marriage,” noted Farouq. “It was an arranged marriage. We had not met face-to-face, only heard about each other.’”

“One month later,” interjected Mahwash in her scant English, “I am Farouq’s fiancée. Three months, finished. We married.” Forty-eight years on, sitting in their sunny Fremont salon, Mahwash and Farouq are a picture of marital bliss. They were courtly and sweet with one another, and nearly every time Mahwash broke into song—as she often does—Farouq became enraptured, sometimes exclaiming that he was falling in love all over again.

“The first person who heard me singing was Ustad Khayal,” said Mahwash, describing the start of her career. (Ustad is an honorific meaning “master.”) Ustad Hafiz Ullah Khayal was a supervisor at the office where Mahwash worked as a secretary, but he also programmed music for Radio Kabul. Upon hearing this secretary sing, he was determined to get her on the air.

Mahwash told him this was impossible, saying, “My husband would kill me.” Not so, it turned out. Farouq recalled, “I said, ‘Okay, I agree.’ Of course, this was not easy for me. I would have to fight with my family, and fight with my in-laws’ family, but I took this responsibility.” Soon, Ustad Khayal gave Farida Gualili Ayoubi Naqshbandi the name by which she would always be known, Mahwash, meaning “like the moon.”

Fearful but excited, Mahwash made her radio debut in 1967, and soon her formal education in music began. A renowned Afghan singer, Ustad Hussain Khan Sarahang, heard her on the radio and invited her to study with him, which she did for two years. Sarahang had learned music from his father and traveled to India to study classical ragas. He returned an ustad, although, as Mahwash and Farouq recalled, he was known by more prosaic titles in Kharabat, Kabul’s musical neighborhood: “Mountain of Music; Crown of Music; Son of Music; Lion of Music; Father of Music.”

n Fremont, Mahwash showed us a black-and-white photograph from Kabul in 1975. She is sitting at the center of a festive informal gathering, her black hair in a tall bun, a coiled lock drooping down to caress the side of her face. She looks pleased. Everyone is smiling. At her side sits the era’s preeminent tabla master, Hashim Chishti, who has just taken Mahwash on as his student. “In our musical culture, when you go to someone to learn music professionally, they hold a ceremony like this, kind of the official announcement,” she explained. The image exudes casual camaraderie among male and female musicians.

“That was the golden time for all Afghans,” Mahwash said wistfully. “Women and men worked shoulder to shoulder. Now, whenever you see Afghanistan on the TV, you see people in turbans or in uniform, with guns on their shoulders. When I see this, I am totally confused. I don’t know where these people came from. I am so sad about what is going on in Afghanistan now….”

|

| The members of Voices of Afghanistan came together in Freemont, California, having emigrated from Afghanistan via Peshawar, Pakistan, at different times. Above left: Flautist Pervez Sakhi and videographer Saeed Ansari. Above right: Rubâb virtuoso and cofounder Homayoun Sakhi. |

|

| Courtesy of De Management |

| In 1970, Farida Mahwash, lower left, was honored by master musicians in Kabul with a gurmany, a ceremony in which she was accepted as one of them by the master musicians of Afghanistan. Later, she had five daughters, and in 1989 fled with her husband, Farouq, to Pakistan, and then to Fremont. |

In 1977, Mahwash performed a song called “O’Bacha” (Hey, Boy), a playful jab at western influences in Afghan life, saying, in part, “Hey, boy, I don’t want to do western dance with you. I don’t want to dance cha cha cha with you. I want to dance Afghan style. I want to dance balkh and logar.”

The song is complex, with many changes of raga and rhythm, “like seven songs in one,” said Mahwash. Another singer had failed to master it after three months of practice, but Mahwash learned it in a day. The country’s new president, Mohammed Daoud Khan, took note of this performance and called together some of the country’s most powerful culture brokers to discuss it. “They spoke among themselves,” recalled Mahwash, “and they approved that I should receive this title: ustad.” She was the first, and is still the only, woman in Afghanistan to receive the honor.

Mahwash’s golden era of artistic openness, with its concert-hall tours around the country and region, came to an abrupt end when Russian tanks rolled into Afghanistan late in 1979. The new regime purged the radio staff, and Mahwash was one of 13 singers summarily dismissed. She was forced to take a job as a typist at the Central Bank of Afghanistan. But two years later, new management at the national radio shifted the politics once again and Mahwash was invited back. She spent the next eight years as an official singer of the state, performing for visiting dignitaries, and touring Eastern bloc nations—Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany—with an ensemble of Afghan musicians.

“Of course, I was thinking about our people, the problems of the people, especially in far villages,” she recalled. “They didn’t know about politicians, the war, communists and capitalists. So when I was traveling through the Russian bloc to do concerts, I focused only on culture, on my art and songs.” But in 1989, the mujahideen resistance was gaining ground on the Russian regime, and the fight came to Kabul.

“The mujahideen used to fire rockets into the cities,” Mahwash remembered. “One rocket hit near my house and near my daughter’s school. I went into a deep depression. We couldn’t handle it anymore. My husband arranged for the family to leave Afghanistan and go to Pakistan.”

This was no easy decision for Farouq, who had to move his wife and five daughters overland to Pakistan in the midst of war. But life in Kabul had become impossible. “That’s why we accepted this horror trip,” he recalled. “There were two choices, life or death. If you want to live, you have to try to move.” Their stay in Peshawar was a relatively brief 18 months. By then, one daughter had established herself in California, and so began the long sojourn in Fremont.

Homayoun Sakhi and his younger brother Pervez were reared in music from the start. Born in 1976 when Mahwash was already a star, Homayoun began beating out rhythms on a tin can as a child, and his maestro father knew right away he was looking at a prodigy. Ghulam Sakhi had been a student of his era’s towering rubâb player Ustad Mohammad Omar (d. 1980), heir to a musical lineage that went back to the 1860’s, when the ruler of Kabul, Amir Sher Ali Khan, brought classically trained musicians from India to perform at his court. They established Kharabat, the artistic neighborhood where the Sakhi family and so many other Afghan virtuosos honed their knowledge and skills. Kharabat’s fostering of Persian, Indian and Afghan musical ideas came together in a distinctive approach to the art of ghazal that became popular all around the country, and Kharabat’s percussionists, singers and rubâb players were legendary.

The rubâb itself is a classical instrument with a folkloric past. It originated in Central Asia and belongs to a family of double-chambered lutes that includes, among others, the Iranian târ, Tibetan danyen and Pamir rubâb. After the rise of Islam, the rubâb was used to play a devotional style of traditional Afghan music called khanaqa. The instrument then had four gut strings for melody and no sympathetic strings. Today it has three melody strings, made of nylon, and 14 or 15 sympathetic steel strings.

The rubâb’s heavy wooden body is constructed in three parts: a carved hull, faceboard and headstalk. Goatskin is stretched over the body’s open face, taut like a banjo, and the melody strings pass through a bridge made from a ram’s horn. The classical rubâb technique developed under the influence of Indian and Persian music is almost like claw-hammer banjo picking, resulting in parallel melodies, incorporating both low and high drone tones interspersed with melody.

|

| “I am a messenger of love,” says 66-year-old Mahwash. “Art generally, and singing especially: It’s all love.” |

“When I was 10 years old,” recalled Sakhi, “I was practicing rubâb every day—eight hours, 10 hours, 12 hours. I learned everything, because I loved all kinds of music. I loved Pashtun music. I loved sitar music. I would listen, and I would say to my father, ‘I want to play this style.’ He would say, ‘Okay.’” Before long, the youngster was picking up ideas from local folklore, Persian classical styles, even guitar music, and developing spectacular technique, playing faster and harder than anyone else on the scene.

“This is an instrument that can play everything,” he told me with the air of an evangelist. “It's not just for Afghanistan.” Indeed not. Sakhi has performed with the Kronos Quartet, the Berlin Philharmonic, the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, jazz and pop musicians and, of course, many, many Indian and Afghan singers.

“Why not?” he asked, refusing to be pigeonholed, even when it comes to his own ethnic identity. The Sakhi family is Dari, but he would not tell me as much. “I am Afghan,” he insisted. “I’m not talking about Pashtun, Dari, Tajik. I am just Afghan.”

In September 2012, Voices of Afganistan spent four days in residence at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, the first American university to offer a Ph.D. in ethnomusicology. Mark Slobin, a professor there since 1971, is one of just three scholars to have made an extensive study of Afghan music before the country was consumed by war.

Slobin impressed the Afghan musicians with images, video clips, recordings and instruments from a time before the younger players were born. He brought Sakhi to Wesleyan’s climate-controlled instrument museum and pulled out a rubâb that had been donated to the university. Sakhi was awed by this specimen and treated Slobin to a detailed analysis of the various repairs and decorations it had undergone over the years—a history only an expert eye could decipher. Sakhi said the instrument dated from the late 19th century, far earlier than Slobin had imagined.

On the eve of the Berkeley concert, Voices of Afghanistan gathered in the living room of the small, modern home Homayoun and Pervez Sakhi share in Fremont. Homayoun came straight from the airport, flying from India to Dubai to Frankfurt to San Francisco, and was exhausted. This did not stop him from running an efficient rehearsal, refining unison melodic passages, reaching over to adjust accompaniments on Khalil Ragheb’s harmonium, tapping out rhythms for the percussionists on the face of his rubâb and, on occasion, gently directing Mahwash herself. These musicians were easy with each other, highly professional and at home in their California milieu.

“Our community is here,” explained Farouq, “our mosques, our wedding salons, offices helping people with immigration, green cards, citizenships, markets selling Afghan food….” Even the town’s surrounding hills, though minute by Afghan standards and always green, provide a distinct reminder of the majestic peaks that flank Kabul. Elder and I experienced all this when Mahwash, Farouq, Homayoun and Aref escorted us around Little Kabul.

We perused Afghan carpets at a showroom in a small roadside mall; the proprietor, thrilled by the visit, agreed to lend five carpets to adorn the stage at the Berkeley concert. We browsed the Zam Zam and Little Kabul markets, which sell imported rice, sauces and saffron from Herat, as well as kites, traditional clothing and jewelry and, of course, CDs and DVDs of Afghan music and film.

There are five Afghan television stations in California, available along with a variety of Central Asian media via satellite. One of those stations was showing an Afghan drama, with the sound turned down, at the Maiwand Kabob House and Bakery, where we feasted on buloni—fried flatbread stuffed with either greens or potatoes—lamb, rice, kofta and green tea. All delicious!

|

| Courtesy of De Management |

| Having performed around the world with classical, jazz and pop ensembles, Homayoun and others in the group visit schools both in the us and in Afghanistan, above. |

As we ate, Elder quizzed Mahwash about her visits to Afghanistan, where she’s returned to perform five times since 2007. Does she see herself as a model for young Afghan women who might aspire to become singers? Mahwash considered this, and firmly said no. “Things have changed. When I was a singer in Afghanistan, I was so modest,” Mahwash said.

Mahwash lamented the way young women in today’s Afghan music, mostly in diaspora, lack serious training or knowledge of tradition. “What about your daughters?” Elder pressed. “If one of them wanted to be a musician or a singer, would she have your support?”

“No,” said Mahwash in English. “No music. It’s too hard a life. Women are not respected for their work.” When she was a young woman, Mahwash chose to pursue music; her goal was not to overturn the social order. It was the Afghan context that made her choice revolutionary. Yet even as she hesitated to recommend this life, Mahwash does dream of establishing a school for girls in Afghanistan—a place to learn music, not celebrity.

When they return to Kabul now, Farouq and Mahwash said the strongest emotion they feel is missing Fremont. Mahwash’s commitment to Voices of Afghanistan is not premised on any illusion of great commercial success; she might do just as well playing at upscale events for Afghan expatriates. Rather, it has to do with a desire to give something back to America for receiving her family and community with such generosity and ease, and for trying to help her deeply troubled homeland.

“I feel so sorry about what has happened in Afghanistan,” said Mahwash, “and especially for those who lost their lives and their loved ones there. God is the God of all human beings, not just Muslims. So I pray for everybody.”

As they returned to the studio with Elder to finish work on their first ensemble recording, Love Songs for Humanity (due out in 2013), the musicians of Voices for Afghanistan all expressed variations of this sentiment. Their art ensures that they remain deeply attuned to their ancestral pasts. It also affords them a powerful vehicle for connecting with so many strangers whom fate has made their neighbors.

|

Banning Eyre is an author, guitarist, radio producer, journalist and senior editor at Afropop.org. His work with Public Radio International’s Afropop Worldwide has taken him to more than a dozen African countries to research local music. He comments on world music for NPR’s All Things Considered, and he recently completed a series on music and history in Egypt for Afropop Worldwide. |

www.demgmt.com

www.voicesofafghanistan.com

www.facebook.com/voicesofafghanistan |