Rose Issa is widely regarded as the leading mover and shaker in contemporary visual art and film from the Arab world and Iran, having built an international platform from her London base in the course of three decades. In 2005 she established Rose Issa Projects, which presents visual art and film, and publishes books and catalogues. Last year she expanded further to a new, larger London exhibition venue where “an ever more mobile society can interact with exceptional art in a space where something takes off,” she says.

Of Lebanese–Iranian heritage, Rose was living in Paris in 1982 when she finished her master’s degree in Arab history and literature. She was unable to return to her home in Lebanon because of the long-running civil war. Art commentator Juliet Highet interviewed her in London.

|

| Ayman Baalbaki, “Wake Up” (2012), installation, 170 x 110 x 80 cm. Rose Issa: “‘Wake Up’ is about constantly moving and changing”. Baalbaki was born in southern Lebanon in 1975, at the outset of an uprooting 15 years of civil war. This installation of bundled belongings topped by a rooster is a “wake-up call about learning from what one loses and also about preparing the present for the future.” |

How did you get from student life in Paris to your position today as the doyenne of the London and global Arab contemporary art scene?

How did you get from student life in Paris to your position today as the doyenne of the London and global Arab contemporary art scene?

1982 was the year Israel again invaded Lebanon. I felt I had to do something, and the only people I knew in Paris were filmmakers and artists—cultural activists. So I arranged a film festival about resistance and occupation, showing the work of regional cineastes. It was very well attended, making mainstream news, and I realized that nobody in Europe was representing contemporary Arab culture. I discovered that there was a growing awareness and need, which is why the Cannes Film Festival approached me for collaboration. I worked with them for several years.

1982 was the year Israel again invaded Lebanon. I felt I had to do something, and the only people I knew in Paris were filmmakers and artists—cultural activists. So I arranged a film festival about resistance and occupation, showing the work of regional cineastes. It was very well attended, making mainstream news, and I realized that nobody in Europe was representing contemporary Arab culture. I discovered that there was a growing awareness and need, which is why the Cannes Film Festival approached me for collaboration. I worked with them for several years.

Then in 1985, Dr. Mohammad Makiya, an Iraqi architect, came to Paris. Part-owner of Al Saqi Books in London, he invited me to launch a gallery in an adjoining space, as its artistic director. So I made London my home. I discovered a cosmopolitan group of westerners who were interested in the Middle East, as well as a large community of Arabs. The Kufa Gallery, as it was called, became such a leading cultural venue that it was clear that people were hungry for art from our region.

After two years, I thought that public institutions like the British Museum, the Barbican, Leighton House Museum and the National Film Theatre offered better platforms of exposure. I felt it was important to get them involved with our culture, specifically its contemporary aspect.

Since those years you have served as an advisor on Arab art to the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery of Jordan, the Museum of Mankind and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, to name just a few. What did you learn from those experiences?

Since those years you have served as an advisor on Arab art to the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery of Jordan, the Museum of Mankind and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, to name just a few. What did you learn from those experiences?

My first brush with public institutions was with the British Museum. I pointed out that their holdings of Arab and Islamic art were exclusively from the past. Why not update them with work by living artists for future generations? What was fantastic about collaborating with inspired people like Venetia Porter [curator of Islamic and modern Middle Eastern art at the British Museum] was that they had the courage to understand this. Venetia had acquired works from me at the Kufa Gallery as early as 1987, many of which were shown in 2005 in the Museum’s groundbreaking “Word Into Art” exhibition.

My first brush with public institutions was with the British Museum. I pointed out that their holdings of Arab and Islamic art were exclusively from the past. Why not update them with work by living artists for future generations? What was fantastic about collaborating with inspired people like Venetia Porter [curator of Islamic and modern Middle Eastern art at the British Museum] was that they had the courage to understand this. Venetia had acquired works from me at the Kufa Gallery as early as 1987, many of which were shown in 2005 in the Museum’s groundbreaking “Word Into Art” exhibition.

|

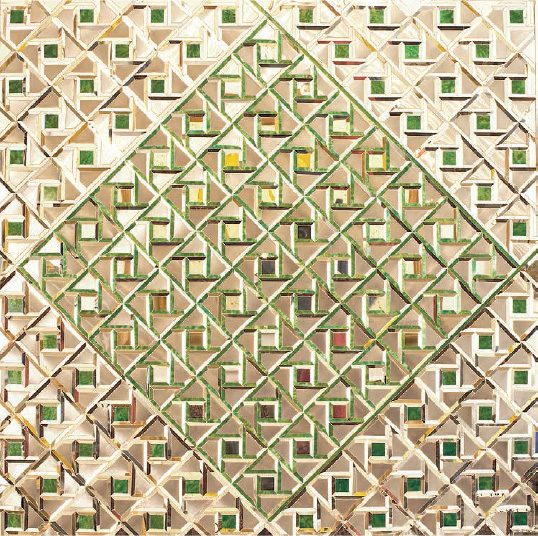

| Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, “Geometry of Hope” (1975), mirror mosaic and reverse-glass painting, 128 x 128 cm. RI: “She created this at the height of her artistic career in pre-revolutionary Iran. This example is one of the few of her older creations to survive the revolution. It shows her mastery of the traditional techniques of mirror mosaic and reverse-glass painting. To these she added the modern industrial materials of aluminum and plastic, creating more lightweight artworks.” |

|

| Dick Doughty |

| Rose with visitors at the Rose Issa Projects booth at Art Dubai, March, 2013. “My job is to promote artists, and their work is also me.” |

It was mainly after working with Tate Britain in connection with their Orientalist exhibition [“The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting”] in 2005 that I decided to get my own space, Rose Issa Projects. I was asked to curate a contemporary response to Orientalism. That project, although prestigious, was frustrating, taking two years and 10 meetings to finalize. I learned that I was spending too much time on what was, in the end, a small solo show. That year I did four exhibitions at Leighton House—a series called “This Is That Place,” introducing the concept of what “the Orient” is now, which the Tate was addressing differently.

What I took away from the Tate experience was actually very useful, because I learned about the criteria of choice of western museums. They are not storage spaces; they invest money and effort in exhibitions. Like them, I have an agenda, and that includes ensuring there is a future for collections from promising artists. I ask myself whether these artists are investing in themselves, because I cannot be the only one to do so. How ambitious are they? How original is their work? Will they take it further? How much richer and more articulate is it becoming? Does it move me, shake me up? And not just me—does it speak to a wider audience?

You currently represent about 20 artists on a long-term basis and about 40 for projects. How do you choose them?

You currently represent about 20 artists on a long-term basis and about 40 for projects. How do you choose them?

There’s no formula—you see the work and you have to trust your eyes and your heart to gauge its aesthetic and human qualities. However, I would say that originality and poetry are the most significant factors for me.

There’s no formula—you see the work and you have to trust your eyes and your heart to gauge its aesthetic and human qualities. However, I would say that originality and poetry are the most significant factors for me.

These days, what is it that distinguishes artists living in the Arab world or Iran from those outside? Does it matter anymore?

These days, what is it that distinguishes artists living in the Arab world or Iran from those outside? Does it matter anymore?

For those in the West, self-promotion is easier, especially if they’ve studied here. However, nobody wants to be labeled or “ghettoized.” These artists don’t want to be just “Arab,” “Iranian” or “Middle Eastern.” They don’t represent governments. They want to be themselves.

For those in the West, self-promotion is easier, especially if they’ve studied here. However, nobody wants to be labeled or “ghettoized.” These artists don’t want to be just “Arab,” “Iranian” or “Middle Eastern.” They don’t represent governments. They want to be themselves.

Do you see yourself as a pioneer?

Do you see yourself as a pioneer?

Well, I deal with living artists, and 30 years ago, few people in the West, if any, knew about Arab artists. So in 1987, when I organized the first Arab Film Festival at the National Film Theatre, I was asked to become their advisor. I got British tv stations to interview the directors, and I participated in television documentaries myself. Then in 1999, I arranged the biggest-ever festival of Iranian cinema, with a publication, and in 2001 the first exhibition of contemporary Iranian art at the Barbican, a high-profile event attended by the uk minister of culture. The Museum of Tehran lent us works for that—the first collaboration between two such public institutions. Earlier, at the Kufa Gallery, I had arranged the premier exhibition of Arab women artists in the uk. I’m always very aware of whether we have enough women in each show or publication in which I’m involved. Is it 50 percent? As a woman curator, their concerns are my concerns. But gender is not an issue as long as we respect each other.

Well, I deal with living artists, and 30 years ago, few people in the West, if any, knew about Arab artists. So in 1987, when I organized the first Arab Film Festival at the National Film Theatre, I was asked to become their advisor. I got British tv stations to interview the directors, and I participated in television documentaries myself. Then in 1999, I arranged the biggest-ever festival of Iranian cinema, with a publication, and in 2001 the first exhibition of contemporary Iranian art at the Barbican, a high-profile event attended by the uk minister of culture. The Museum of Tehran lent us works for that—the first collaboration between two such public institutions. Earlier, at the Kufa Gallery, I had arranged the premier exhibition of Arab women artists in the uk. I’m always very aware of whether we have enough women in each show or publication in which I’m involved. Is it 50 percent? As a woman curator, their concerns are my concerns. But gender is not an issue as long as we respect each other.

|

| Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Museum |

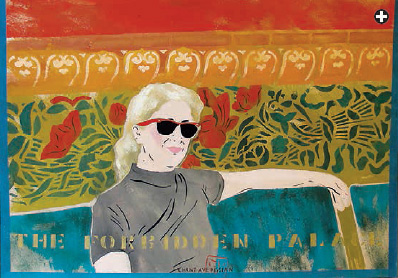

| Chant Avedissian, “Al-Watan al-Arabi” (“The Arab Nation”) (2008), pigments and gum arabic on corrugated cardboard, 250 x 300 cm. RI: “The Egyptian artist captures the spirit of the Arab nation in this eponymic work that features Um Kulthum, whose songs from Cairo transfixed listeners from Morocco to Lebanon and beyond for decades until her death in 1975. This stencil also features Pharaonic, Islamic and socialist symbols, highlighting the multi-layered history of his country and region.” |

What influence and contribution do you think you and Rose Issa Projects have made to the burgeoning of contemporary Arab and Iranian art?

What influence and contribution do you think you and Rose Issa Projects have made to the burgeoning of contemporary Arab and Iranian art?

I can’t be the judge of that. Time will tell. But what I have done in the past 30 years is to give visibility to wonderful, virtually unknown artists. I can say that many of those who have high profiles today exhibited with me at some stage in London, and in most cases this was their first show outside their country of origin. I also encouraged British and American public institutions such as the British Museum, the [Smithsonian Institution’s] Sackler Gallery, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan Museum of Art to acquire relevant works. In 1995, I had an exhibition of Chant Avedissian’s work in London and the Smithsonian acquired almost the entire show. An influential exhibition I organized at the Barbican that same year, called “Signs, Traces & Calligraphy,” really put me on the map as a curator. It traveled to the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, and then to the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., which bought most of it. It was a key moment when the work of North African and Arab artists was being appreciated and purchased in the United States.

I can’t be the judge of that. Time will tell. But what I have done in the past 30 years is to give visibility to wonderful, virtually unknown artists. I can say that many of those who have high profiles today exhibited with me at some stage in London, and in most cases this was their first show outside their country of origin. I also encouraged British and American public institutions such as the British Museum, the [Smithsonian Institution’s] Sackler Gallery, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan Museum of Art to acquire relevant works. In 1995, I had an exhibition of Chant Avedissian’s work in London and the Smithsonian acquired almost the entire show. An influential exhibition I organized at the Barbican that same year, called “Signs, Traces & Calligraphy,” really put me on the map as a curator. It traveled to the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, and then to the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., which bought most of it. It was a key moment when the work of North African and Arab artists was being appreciated and purchased in the United States.

|

I started my own publishing house in 2005 because there is an acute shortage of written material about contemporary Arab/Iranian art and film. How can you do an M.A. or Ph.D. without source material? How can teachers help you or judge your work without it? Our new central London location [at 82 Great Portland Street] is already having a significant impact, as there are several art schools in the area whose students drop by the gallery. I give them publications for their libraries. Now the teachers are coming in! After decades under the radar in art and film books, we are producing many key texts. These include my books, exhibition catalogs from “Iranian Contemporary Art,” “Iranian Photography Now,” “Arab Photography Now” and “Signs, Traces & Calligraphy,” as well as monographs on individual artists. In a sense, we are rewriting our own history.

How is the impact of your work unique, as compared to that of other art entrepreneurs in London or elsewhere?

How is the impact of your work unique, as compared to that of other art entrepreneurs in London or elsewhere?

The uniqueness comes from the fact that I speak both Arabic and Persian and that it was my passion that drove me at a time when no one was promoting these artists in the West. Sometimes I feel like a prisoner of my passion, working 24/7! At the Kufa Gallery, we had such a tight budget that we just covered costs but couldn’t produce catalogs. Later, members of the Africa ’95 organization approached me, saying they knew nothing about North African art—they were more sub-Saharan specialists. So I co-organized a film festival season, exhibitions and publications. But they did not allocate any budget for these projects, so I raised the funds. Before I got my own space, I curated 20 shows at Leighton House Museum, for which we never asked a penny, and they never charged us. I arranged sponsorship for everything, including shipping costs and hosting the artists. Somehow, I’ve always managed to find just enough to make things happen. I learned a lot from that process.

The uniqueness comes from the fact that I speak both Arabic and Persian and that it was my passion that drove me at a time when no one was promoting these artists in the West. Sometimes I feel like a prisoner of my passion, working 24/7! At the Kufa Gallery, we had such a tight budget that we just covered costs but couldn’t produce catalogs. Later, members of the Africa ’95 organization approached me, saying they knew nothing about North African art—they were more sub-Saharan specialists. So I co-organized a film festival season, exhibitions and publications. But they did not allocate any budget for these projects, so I raised the funds. Before I got my own space, I curated 20 shows at Leighton House Museum, for which we never asked a penny, and they never charged us. I arranged sponsorship for everything, including shipping costs and hosting the artists. Somehow, I’ve always managed to find just enough to make things happen. I learned a lot from that process.

What do you tell people of Arab origin who aren’t familiar with the art you exhibit to help them appreciate it and understand it?

What do you tell people of Arab origin who aren’t familiar with the art you exhibit to help them appreciate it and understand it?

|

| Jowhara Al Sa’ud, “Butch” (2012), C-41 print mounted on aluminum, 122 x 152 cm. RI: “She represents a generation of Saudi artists in their 30’s who have found their voice in an environment of traditional representational restrictions and lack of a well-developed fine-arts educational infrastructure. Made by drawing on a photographic negative, this image says, ‘I can be feminine and, despite tradition, do jobs normally done by men.’ But most of all, it is beautiful photography.” |

I would say, “Look and ‘iqra”—“read,” which is the first word of the Qur’an. Gain knowledge. Learn about the positive side of your culture. We’ve done and are doing so much. A lot of Arabs don’t love themselves sufficiently. Love is about knowledge—the more you know, the more you love. Go to galleries and museums, and complain if there’s not enough about our culture today. Governments shouldn't underestimate art. As to art education in our region, there’s never enough. There are few courses teaching our own culture, and insufficient teachers qualified in it. But the situation is improving, as more books are being published, and more scholars are invited from abroad to lecture and share their knowledge.

I would say, “Look and ‘iqra”—“read,” which is the first word of the Qur’an. Gain knowledge. Learn about the positive side of your culture. We’ve done and are doing so much. A lot of Arabs don’t love themselves sufficiently. Love is about knowledge—the more you know, the more you love. Go to galleries and museums, and complain if there’s not enough about our culture today. Governments shouldn't underestimate art. As to art education in our region, there’s never enough. There are few courses teaching our own culture, and insufficient teachers qualified in it. But the situation is improving, as more books are being published, and more scholars are invited from abroad to lecture and share their knowledge.

You have said, “We are all cultural nomads.” How so?

You have said, “We are all cultural nomads.” How so?

It’s impossible to be insular. We have to know about each other. Everything is interconnected with our chosen subject. Now everybody’s a nomad—artists, curators or representatives of public institutions—we’re all traveling and meeting halfway, in a space where something takes off.

It’s impossible to be insular. We have to know about each other. Everything is interconnected with our chosen subject. Now everybody’s a nomad—artists, curators or representatives of public institutions—we’re all traveling and meeting halfway, in a space where something takes off.

You have also said that the hubs of global culture are shifting away from London, Paris and New York. Where are they going, and why? Is your success contributing to these shifts?

You have also said that the hubs of global culture are shifting away from London, Paris and New York. Where are they going, and why? Is your success contributing to these shifts?

There are many more hubs now. Today it’s Shanghai, Hong Kong, Dubai, Delhi and Brazil—maybe tomorrow South Africa. Art has to do with economics, and if that’s where the burgeoning economies are, then those are the places where art will blossom. People are making money out of our contemporary art now, and there are many more auctions, fairs and biennales. Everybody is competing. In Dubai, several collectors have recently created their own public foundations, and more and more art spaces are opening. Let them compete—it’s fantastic!

There are many more hubs now. Today it’s Shanghai, Hong Kong, Dubai, Delhi and Brazil—maybe tomorrow South Africa. Art has to do with economics, and if that’s where the burgeoning economies are, then those are the places where art will blossom. People are making money out of our contemporary art now, and there are many more auctions, fairs and biennales. Everybody is competing. In Dubai, several collectors have recently created their own public foundations, and more and more art spaces are opening. Let them compete—it’s fantastic!

If I take any credit for the success of Rose Issa Projects, it’s because I persevered and believed in the work of these artists. So why not make it accessible to others? If it is beautifully and originally expressed, why not share it?

In describing artists working under cultural and political constraints, you’ve used the term “loophole language.” What does it mean?

In describing artists working under cultural and political constraints, you’ve used the term “loophole language.” What does it mean?

When I did the first festivals of Iranian art and film, I thought, “How can artists facing so many restrictions, so much censorship and with so little money create such wonderful art and films?” For example, in Iranian films, a couple can’t be seen kissing, but in a phone conversation, they can certainly say something. The best way to circumvent censorship is to learn how to express yourself despite the restrictions, to find a language that communicates with your public. These are the loopholes—expressing your concerns without hurting anyone, doing it gently, without aggression, so you can make people think.

When I did the first festivals of Iranian art and film, I thought, “How can artists facing so many restrictions, so much censorship and with so little money create such wonderful art and films?” For example, in Iranian films, a couple can’t be seen kissing, but in a phone conversation, they can certainly say something. The best way to circumvent censorship is to learn how to express yourself despite the restrictions, to find a language that communicates with your public. These are the loopholes—expressing your concerns without hurting anyone, doing it gently, without aggression, so you can make people think.

If you had three wishes for the future of Arab art, what would they be?

If you had three wishes for the future of Arab art, what would they be?

|

| Artist Chant Avedissian used a photo of Rose Issa for this image titled “Forbidden City, China” (2000), made with pigments and gum arabic on corrugated cardboard, 50 x 70 cm. |

Actually, I would like four wishes. The first is peace, in order for us to have museums, galleries, collectors and artists staying home. In Syria there were plans for two museums of contemporary art, but that’s finished for the time being. Second, education. Knowledge makes people interested in art. Third, work, so that we have the economic means for more cultural life. Lastly, beauty. There are lots of artists who make ugly things to express themselves, but I’m not interested in that. There are enough ugly things in life. Beauty elevates. It’s uplifting, and it makes us more generous to each other. The art I promote is about beauty, originality and justice—about contributing to a better world.

Actually, I would like four wishes. The first is peace, in order for us to have museums, galleries, collectors and artists staying home. In Syria there were plans for two museums of contemporary art, but that’s finished for the time being. Second, education. Knowledge makes people interested in art. Third, work, so that we have the economic means for more cultural life. Lastly, beauty. There are lots of artists who make ugly things to express themselves, but I’m not interested in that. There are enough ugly things in life. Beauty elevates. It’s uplifting, and it makes us more generous to each other. The art I promote is about beauty, originality and justice—about contributing to a better world.

|

Writer, photographer and tour lecturer Juliet Highet (art@juliethighet.com) is a specialist in the heritage and contemporary arts of Africa, the Middle East, South Asia and Southeast Asia. She is the author of Frankincense: Oman’s Gift to the World (Prestel, 2006) and is working on a book series called “The Art of Travel.” She lives in England. |

| www.roseissa.com |