|

| Top: the stapleton collection / bridgeman art library (details) |

Can you imagine a world without salsa? Or Tabasco sauce, harissa, sriracha, paprika or chili powder?

|

|

|

|

Typical of culinary transformations brought on by Old World trade in New World capsicum chiles were the changes to the simple, classic lamb sausage of North Africa and the Middle East called mirkas or merguez. While a 13th-century recipe spiced it warmly with black pepper, cinnamon and coriander, today merguez is defined by the brash heat of dried capsicums and is enjoyed from New York to Hong Kong.

Author Deana Sidney presents one home recipe each (see below) for pre- and post-capsicum merguez—and then takes a video tour of today's merguez makers and fans in New York City. |

» View Recipes |

I asked myself that question after I found a 700-year-old recipe for one of my favorite foods, merguez—North Africa’s beloved lamb sausage that is positively crimson with chiles. The medieval version was softly seasoned with such warm spices as black pepper, coriander and cinnamon instead of the brash heat of capsicum chile peppers—the signature flavor of the dish today.

The cuisines of China, Indonesia, India, Bhutan, Korea, Hungary and much of Africa and the Middle East would be radically different from what they are today if chiles hadn’t returned across the ocean with Columbus. Barely 50 years after the discovery of the New World, chiles were warming much of the Old World. How did they spread so far, so fast? The answers may surprise you—they did me!

I learned that Mamluk and Ottoman Muslims were nearly as responsible for the discovery of New World peppers as Columbus—but I’m getting ahead of myself.

The global pepper saga begins in the first millennium bce with the combustible career of another pepper—black pepper (Piper nigrum) and its cousins, Indian long pepper and Javanese cubeb. Although Piper nigrum was first grown on the Malabar Coast in India, the taste for it enflamed the ancient world: No matter what the cost—and it was very high—people were mad for pepper. The Romans, for example, first tasted it in Egypt, and the demand for it drove them to sail to India to buy it. In the first century, Pliny complained about the cost: “There is no year in which India does not drain the Roman Empire of fifty million sesterces.”

In one sense, the whole global system of trade—the sea and land routes throughout the known world that spread culture and cuisine through commerce—was engaged with the appetite for pepper, in its growth, distribution and consumption.

|

| private collection / bridgeman art library |

|

| Top: This sketch of the coast of “La Española” is attributed to Columbus’s own hand, from his first voyage. He also recorded that, in response to being shown samples of black pepper, locals guided him and his crew to abundant allspice berries, shown dried above. |

Not surprisingly, vast wealth came from the control of access to black pepper. India held the secrets of its cultivation and was the sole supplier; Silk Road trading routes throughout China and the Middle East were its primary delivery system.

The decline of the Mongol Empire, which had protected the Silk Roads, and the subsequent fall of Byzantium in 1453, began to fracture the great trading partnerships; warring factions began implementing embargoes along the land routes. The Mamluks and the Ottomans controlled choke points along the land and sea routes and levied punishing taxes on goods moving through their domains. This made the land routes unaffordably expensive, so if Europe was to have pepper, a new sea route had to be found to get it.

Both possible routes were perilous. Sailing around the African continent into the Indian Ocean had been proved possible in 1488 by Bartolomeu Dias of Portugal, thanks in part to Arab navigators, cartographers and sailors. Spain was left with the other option: to sail west across the uncharted Atlantic into mare incognitum and hope to reach India from the other side.

Columbus took advantage of a Portuguese discovery, the volta do mar, a great circular current, or gyre, caused by the earth’s rotation, one of two in the Atlantic Ocean. It shortened his travel time considerably, allowing him to reach what he thought was India (but that was actually a Caribbean island—Samana Cay, Grand Turk, the Plana Cays, Mayaguana and Conception Island are all possibilities) when his crew was on the verge of mutiny. Columbus began searching for the spices and other treasures of India.

|

| biblioteca estense / bridgeman art library |

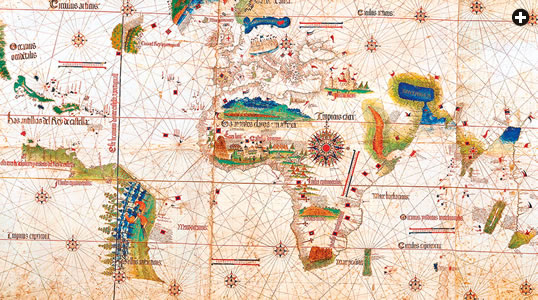

| The world BC (“Before Chiles”) was for more than 1300 years defined by the map drawn by Claudius Ptolemy of Greece, shown above in a 15th-century copy. The Indian Ocean is shown as a closed sea, little of Africa shows below the equator, and the Americas are absent altogether. |

In the journal of his voyage, the entry for November 4, 1492 reads (in Samuel Eliot Morison’s translation): “The Admiral showed to some of the Indians there cinnamon and pepper (supposedly of what he had brought from Castile to show) and they recognized it, it is said, and by signs told him that in the neighborhood there was much of it.” The allspice berries they brought him smelled like cinnamon and pepper, but they were not the Piper nigrum he had hoped to find. In an early example of hopeful rebranding, Columbus called the new spice pimento, after the Spanish pimienta, black pepper.

A month later, Columbus found another kind of pepper: the capsicum pepper that is now familiar—and indispensable—around the world. The journal entry for New Year’s Day, 1493, reads, “The spicery that they eat, says the Admiral, is abundant and more valuable than either black or malagueta pepper [grains of paradise]. He left a recommendation to those whom he wished to leave there, that they should get as much as they could.” The “Indians” called this pepper aji or axi. Two weeks later, the journal records, “There is also much axi, which is their pepper and is stronger than pepper, and the people won’t eat without it, for they find it very wholesome. One could load 50 [ships] a year with it in Hispaniola.”

Enslaved Africans were fed “slabber sauce”—a mash of capsicum peppers, flour and oil—poured over beans to keep them alive during the horrible sea journeys they were forced to endure. Portuguese sailors ate capsicums the way English sailors would eat limes, to ward off the diseases of long sea voyages, and they doubtless shared this secret with seaman of other nationalities.

|

| image asset management / alamy |

| Above: Produced in Portugal between 1500 and 1502, the Cantino world map shows the north-to-south line, in the left quarter of the map, stipulated by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. Spain received control westward, and Portugal eastward, of the line. Spain gained the greater territory, but Portugal held Brazil, from which it monopolized its newfound maritime route around Africa, which relied on the South Atlantic gyre, below. |

|

Indians, especially poor Indians, took to capsicum chiles very quickly, and for once, this benefit was recorded. Indian food scholar K. T. Achaya discovered that South Indian composer Purandaradasa (1480—1564) had called chiles “savior of the poor, enhancer of good food, fiery when bitten.”

The “spicery” Columbus was introduced to had by then been a valued food crop in the New World for some 6000 years. The fleshy, pungent fruits of a plant of the nightshade family, capsicum peppers (Capsicum annuum) contain a tasteless, odorless chemical called capsaicin that gives them a “bite” in the eater’s mouth, warms his body and—thanks to the brain’s release of endorphins in response to the burn—lifts his spirits.

Though it wasn’t the black pepper he had hoped to find, Columbus had an optimistic view of the value of his new pepper, and he surely included aji in his presentation of New World plants to his royal patrons. Though Ferdinand and Isabella seem to have been unimpressed, capsicum peppers proved a popular product in an increasingly fast-moving world-trading network.

Jean Andrews, probably the foremost authority on chile history, believed the Portuguese had capsicum peppers even before they sailed to Brazil in 1500—thanks to Columbus. That could be true, since Spanish ships often docked at Portuguese-controlled harbors in the Canary Islands, at Cape Verde and in the Azores—all stops for ships traveling to and from Africa, the Mediterranean and later India and the New World. Crops, livestock, spices, gold, ivory, slaves—everything came through these islands on the way to and from Lisbon, and surely crews exchanged or sold goods and information.

More specifically, Columbus stopped at the Azores and stayed in Lisbon for a week—even meeting the Portuguese king—before returning to Spain from his first voyage to the New World. For this reason, Andrews and many other pepper scholars feel that it’s entirely possible that Capsicum seeds were shared with the court, or traded by Spanish seamen, as exciting New World novelties as early as 1493. They believe that the capsicums that proliferated so early in the Old World were from Columbus’s seeds (Capsicum annuum var. annuum) and not those that the Portuguese would later have found in Brazil (Capsicum frutescens or chinense). Nonetheless, it was the Portuguese and not the Spanish who spread capsicums far and wide as they traveled the trade routes that they had established in the East, Africa and then India. Within 20 years, capsicums were on their way into pots and onto plates all over the Old World.

Hungarian physiologist Albert Szent-Györgyi received a Nobel Prize in 1937 for isolating vitamin C, using vitamin-rich capsicums, and elucidating the citric-acid cycle. Vitamin C is among the ingredients that made capsicums a highly beneficial addition to the diet of poor people around the world.

Capsicum peppers went by many names when they were first introduced. They were known as Pernambuco pepper after a Portuguese settlement in Brazil, or Calicut pepper after an important spice port in India, but also went by the native name aji, axi or, in India, achi. In Java the Portuguese called them Spanish peppers, as Germany and Sweden still do. Chile, an Aztec Nahuatl word, came to be used later.

In 1984, historian C. R. Boxer suggested that the Portuguese merchant ships that carried black pepper from Goa to Lisbon might have brought capsicums back to India on their return voyages. Jean Andrews wrote that some thin dried capsicum peppers are still referred to as kappal molokai in Calicut—“pepper from the ship.”

|

| bilkent university / wikimedia commons |

In 1513, Ottoman cartographer Piri Reis examined 14 sources to produce this map whose rhumb lines predate cartographic latitude and longitude, and of which only this fragment, showing West Africa, the South Atlantic and the Americas, survives. By this time, chiles had begun reaching many Old World ports, the Middle East and parts of Asia, and they were growing in the Azores, other Atlantic islands and North Africa. |

Sixteenth-century botanist Matthias de Lobel suggested the Portuguese were exporting capsicums from Goa early in the 16th century, as well as black pepper: Capsicums existed in Indonesia by 1510, and pepper authority Dave de Witt says capsicums were growing in the Azores, Madeira and Cape Verde by 1516, as well as along the west coast of Africa, where Portugal had established forts and trading posts. Then, with help from the Persians, Turkey and Portugal reached détente in the 1550’s, and the spice route was open again. Surely capsicum peppers were traded in the newly accessible Middle Eastern markets, with sailors the likely merchants.

It wasn’t just the Portuguese doing the spreading. Venice was still trading with Europe and most of the Muslim world. Spain, Portugal and the Ottoman Empire continually fought and traded, and trade and military engagements from India to North Africa assured interaction between nations as ships were captured and cargos redistributed by the victors. When Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Lawgiver (called “the Magnificent” in Europe) drove through the Balkans and conquered Hungary in 1526, capsicum peppers came too, in the gardens that his army planted to feed the troops, and though the Ottomans eventually left, the capsicums stayed. By 1569, a Hungarian aristocrat listed Türkisch rot Pfeffer (Turkish red pepper) among the plants in her garden, and in no time at all paprika, a Capsicum annuum variety, had conquered Hungarian cuisine at all economic levels. In his 1963 book on paprika, Hungarian historian Zoltan Halasz said that capsicum pepper was first used by Hungarian peasants, herdsmen and fisherman, who would have had close links to the Ottoman commissariat.

Developmental psychologist Jason Goldman said, “Hot pepper consumption has a positive effect on your mental and physical health. When you eat a hot pepper, pain receptors in your mouth react with the capsaicin. This reaction also triggers an endorphin release…. This endorphin release produces a natural high that resembles a “runner’s high.” This overall feeling of well-being also might act as a natural pain reliever if you are suffering from body pain.”

Not everyone loved capsicums when they were first introduced. The Spanish, who had brought them in the first place, only grew them as garden ornamentals. Italy and even Portugal did not take to them wholeheartedly either. European monastery gardens seemed to have had the most interest in propagating them in the early part of the 16th century. Northern European countries were indifferent to them save as a curiosity—although they were growing in Germany by 1542, probably thanks to Ottoman traders, who got yew wood for their bows, among other products, from Germany.

|

Dried chiles shipped well worldwide. From top-left: New World Capsicum annuum varieties include guajillo, ancho and New Mexico; a smaller Capsicum frutescens variety called “birdseye” chiles spread wild in Africa after birds spread their seeds from early gardens, and they are now common also in Southeast Asia; “Indian” chiles are among the most common varieties in India, which today grows and exports more chiles than any other nation. Bottom-left: Three popular capsicum peppers that took root in the Middle East—Maraş, Urfa and Aleppo, shown below in their flaked form—are used in dishes throughout the region. Bottom-right: Fresh serrano, poblano and ripe jalapeño peppers. |

In fact, capsicum peppers did not become a popular culinary item in much of Europe for hundreds of years. Food historian Ken Albala proffered a theory for this when he wrote that “merchants had compelling reasons to maintain their trade in black pepper to the east. And thus they don’t mention, let alone carry, chilies. Nor do they appear in European cookbooks until the end of the 17th century.” Of course, this doesn’t mean they weren’t being eaten by the lower classes, for culinary historians agree that there was precious little written of peasant cooking or gardening during that time.

For that reason, it is difficult to pin down the early impact of peppers. Records of pepper crops are virtually non-existent. Andrews felt they were ignored because capsicum peppers were considered “garden crops” both in European estate ledgers and in the Ottoman Empire’s scrupulous records, and as such were neither taxed nor recorded. But it’s not much of a stretch to assume that capsicum peppers tagged along with corn and New World beans—valuable crops that were recorded—and were traded by sailors who were given them as their voyage-portion while their masters dealt in vastly more valuable black pepper and other commodities.

How do peppers break down in world cuisines? India uses Capsicum annuum and Capsicum frutescens or chinense. (The hottest peppers, like the famous “ghost pepper,” are mostly Capsicum chinenense or frutescens). The Turks use Capsicum annuum, and in some localities sun-dry them and then cover and “sweat” them at night. China has Capsicum annuum and chinense. Korea uses Capsicum annuum, and Hungary uses many varieties of Capsicum annuum to make its famous range of paprikas. African chiles are mostly Capsicum annuum, but all are available on that continent. Morocco has a great variety of peppers, but most are Capsicum annuum varieties.

Aside from intentional planting, natural dispersal by birds spread capsicum peppers far and wide. Unlike mammals, birds are not affected by capsaicin, but like to eat the brightly colored fruits. Lower classes who could never afford black pepper could easily grow capsicums—and they had good reason to do so: Peppers improved not only the flavor of food, but—unbeknownst to their consumers—also its nutritional quality. Throughout the Middle East, China and Africa, many cultures that had survived on rice or grain diets thrived with the addition of peppers. Anthropologist E. N. Anderson wrote, “Perhaps no culinary advance since the invention of distilling had had more effect than the propagation of chili peppers in the Old World..... Not only did it incalculably benefit the cuisine of all those peoples civilized enough to accept it, it also is high in vitamins A and C, iron, calcium, and other minerals; is eminently storable and usable in pickles; can be grown anywhere under any conditions.…”

Indians, especially poor Indians, took to capsicum chiles very quickly, and for once this benefit was recorded. Indian food scholar K. T. Achaya discovered that South Indian composer Purandaradasa (1480–1564) had called chiles “savior of the poor, enhancer of good food, fiery when bitten.” Portuguese sailors ate capsicums the way English sailors would eat limes to ward off the diseases of long sea journeys, and they doubtless shared this secret with seaman of other nationalities. More grimly, enslaved Africans were fed “slabber sauce”—a mash of capsicum peppers, flour and oil—on the horrible sea journeys they were forced to endure.

Charles Perry, food historian and translator of Arab cookbooks, observed that “Persian merchants from Khorasan (a region that is now part of Iran, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan) introduced red pepper to Kashmir and Nepal, because the local word for chili there is khorsani.” That northern route also brought chiles to China’s landlocked hot-chile provinces of Szechuan and Hunan, perhaps in the packs of traveling Indian Buddhists or by those Persian merchants still using the ancient routes—trading spices for Chinese porcelain and silk.

|

| Today, most fresh chiles distributed by global supermarket grocers are varieties of Capsicum annuum. |

Remarkably, in just over 50 years, capsicum peppers were global. The love for the heat of black pepper—which comes from the alkaloid piperine—gave way to the charms of the more potent capsaicin of capsicum peppers. Food historian Ken Albala remarked, “Chili peppers are among the few foods that spread almost immediately after the discovery of the Americas to the whole world. Think of Thailand, India, Sichuan, or even Hungary for that matter, without chili peppers. I have a theory why. Unlike black pepper, [capsicums] can grow pretty much anywhere and don’t need to be imported from the tropics. So they stand in almost everywhere as a hot spice.”

Nonetheless, some cultures were slow to warm to peppers. The Persians, among the earliest traders in both black and red peppers, did not take to them wholeheartedly: There’s little use of either in Persian cuisine. Charles Perry observed, “Well, the Persians do use red pepper in some dishes, such as khoresh-e bamyeh (okra stew—something about okra just demands red pepper), but their cuisine was never very peppery before chilies arrived.”

Many of the cuisines of the Middle East have embraced capsicum peppers completely, often in the form of locally grown varieties, for Capsicum annuum hybridizes promiscuously. Markets all over Turkey and Syria are rich with many varieties, both fresh and dried and ground or flaked, named after their “home” cities: Maraş, Urfa, Aleppo and so on.

Africa loves pili pili—Swahili for “pepper pepper” (also known as piri piri or bird’s-eye chile). It is grown in Malawi, South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, South Sudan and southern Ethiopia; it is cultivated commercially in many of these countries, as well as in India and Indonesia. The Portuguese piri piri hot sauce is eaten all over Africa.

Szechwan cuisine is virtually synonymous with hot pepper. Koreans eat more capsicum peppers per capita than any other country: It is an ingredient in their kimchi and gochujang. Bhutan is mad for peppers—its pepper-full ema datshi is the national dish. Southern India loves the heat of its vindaloo dishes and grows much of the world’s total capsicum crop—far more than South America or Mexico. And even today, Louisiana hot sauce is becoming popular in previously bland corners of the Middle East, thanks to visiting American oil workers.

Andrews notes that the word pepper had confusing beginnings. The long pepper, pippali, got its name from the sacred fig, peppul. Pippali became the name for black pepper as well. Unlike capsicum peppers, both long pepper and the more familiar black peppercorn are members of the same Piper family.

What variety of Capsicum pepper wins the world popularity contest, you may ask? The person to answer that is botanist W. Hardy Eshbaugh, who spent years tracking peppers from their beginnings in Bolivia. In his article “Peppers: History and Exploitation of a Serendipitous New Crop Discovery,” Eshbaugh said, “Capsicum annuum is the best known domesticated species in the world. Since the time of Columbus, it has spread to every part of the globe.” A Purdue University article declared, “Capsicum chinense was also discovered at an early date and spread globally but to a lesser extent than C. annuum. The more limited global expansion of this species is most probably related to its later discovery in South America and the competitive edge enjoyed by C. annuum, which was firmly established in the Old World before C. chinense was introduced there.”

The reason capsicum peppers have become so popular is clear. If you had only a bit of grain and vegetable to eat, a pinch of capsicum powder would make your meal more emphatic and appealing; a piece of capsicum chile in your dish would add vitamins to your beans and rice. Cooks tasted the new peppers and added them to what they were already cooking as an exciting new note in their culinary vocabulary. One taste led to another and so it continues today.

How did cuisine change with peppers? The answer is demonstrated with the “before and after” recipes for lamb sausage that first led me down the pepper trail. You can see firsthand when you compare the “before” recipe from the 13th century and the “after” version of the recipe, which is rich with chiles. Both are delicious, but have very different personalities—think scholar vs. adventurer!

Here is a translation of the original recipe for mirkas (merguez sausage) from the 13th-century cookbook Al Andalus, translated by Charles Perry:

It is as nutritious as meatballs (banadiq) and quick to digest, since the pounding ripens it and makes it quick to digest, and it is good nutrition. First get some meat from the leg or shoulder of a lamb and pound it until it becomes like meatballs. Knead it in a bowl, mixing in some oil and some murri naqi’, pepper, coriander seed, lavender, and cinnamon. Then add three quarters as much of fat, which should not be pounded, as it would melt while frying, but chopped up with a knife or beaten on a cutting board. Using the instrument made for stuffing, stuff it in the washed gut, tied with thread to make sausages, small or large. Then fry them with some fresh oil, and when it is done and browned, make a sauce of vinegar and oil and use it while hot. Some people make the sauce with the juice of cilantro and mint and some pounded onion. Some cook it in a pot with oil and vinegar, some make it rahibi with onion and lots of oil until it is fried and browned. It is good whichever of these methods you use.

|

Deana Sidney (deanasidney@gmail.com) is a New York film production designer who also writes about food, style and history and regularly attends the Oxford Food Symposium. Readers of her blog “Lost Past Remembered” often come for the recipes and stay for the stories. |