Young men and women on motorcycles and motor scooters pull through a tall gate and park in the courtyard. It’s the first day of a new semester at the Unani Medical College in Pune, India, and students gather to catch up with each other as they walk toward the three-story classroom building. Their conversations mix Urdu and English, and some carry American textbooks on anatomy and physiology. From this first moment, Unani’s unique blend of ancient and modern, western and eastern, brings up the questions that often come when encountering a different way of medical thinking: Where did it come from? What does it offer?

|

| The main entrance to the Unani Medical College, in Pune, India. |

The term unani refers to the ancient Greek province of Ionia, located in what is today western Turkey. According to Qaisar Khan, a professor at the college and a specialist in Unani history, the deepest roots of this type of medicine lie with the Greek and Roman concept of the body’s four elements—earth, air, fire and water—as well as the idea that illness occurs when the body’s essential physical states—mainly hot and cold, dry and wet—are out of balance. Imbalance affects many organs, such as the digestive tract, liver, heart and brain. Through observation of pulse, breath, eyes, urine and stool, a doctor can understand the imbalance and correct it, not only with medicines, but also with recommendations for rest, therapies and changes in diet and personal behavior. Medicinally, Unani looks first to compounds of herbs with long traditions of treating particular conditions, such as problems of the digestive tract or high blood pressure. But unlike other herb-based alternate medical systems, Unani medicines, Khan says, are produced from the whole plant, rather than from extracts of the active ingredient.

Unani’s history, he explains, only began with Greece and Rome. Even then, he points out, medical practice always consisted of competing treatments, ideas and schools of thought in which doctors discussed theories and sought, copied and improved upon cures. The classical world of shared medical ideas and practices thus encompassed much of what is today the Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa, and may even have extended to India: Sanskrit and Greek medical texts show striking similarities in their uses of the idea of four essential elements, as well as the correspondence of those elements to four “humors”: wet, dry, hot and cold.

By the early first century ce, both texts and archeology confirm that commercial trade and the exchange of ideas between Rome and India had become frequent and commonplace. Medical ideas flowed farther still, as Sanskrit scholars worked in Central Asia along the Silk Roads and a medicinal trade flourished that linked South India to China.

|

|

top: biblioteca estense / bridgeman art library;

Above: mark de fraeye / wellcome images |

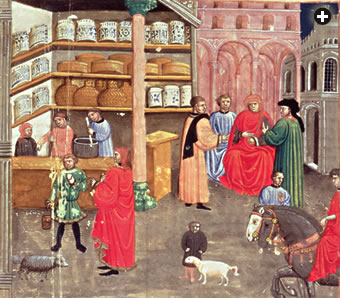

| Top: This 14th-century illustration from one of the many editions of Ibn Sina's five-volume Canon of Medicine depicts both consultation and a pharmacy. The simple process of mixing natural, plant-based medicines remains much the same today for this Unani pharmacist, above. |

In the sixth century, the medical school at Gundeshapur, in what is now western Iran, brought together doctors from the Byzantine Empire, Persia, India, China, Syria, Greece and Rome, and they included Buddhists, Hindus, Nestorian Christians, Confucians and Jews. After 638, under Muslim rule, the Gundeshapur academy continued for several centuries, and it was likely a model for the Abbasid Dynasty’s House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where the eighth-century caliph Harun al-Rashid founded an extensive project to translate Greek and Latin texts into Arabic.

In the late eighth century, one of Harun al-Rashid’s ministers sent emissaries to India not only in search of medicines, but also in search of Indian physicians, who indeed came and settled in Baghdad, where traditional Indian medical texts were translated into Arabic. By the ninth century, Islamic pharmacopeias routinely offered Indian medicines alongside those of traditional Greek medicine.

With the advent of paper, copies of medical books circulated farther and with greater frequency, from Baghdad to Persia to the caravan cities of the Silk Roads, east as far as Afghanistan and west to North Africa and Muslim Spain. They appealed to literate elites, curious about the body, health, diet and the practical business of curing illness. By about 900 ce, the movement of both books and medical practitioners constituted a broad intellectual network of treatises, letters, comments and questions, from Bukhara to Cairo, Baghdad to Morocco.

The works of the two most famous doctors of the Islamic world in this period reflect this broad approach to health that Muslim physicians developed from classical foundations: Al-Razi (865–925, called Rhazes in the West), who practiced in Baghdad and in Rayy, near Tehran, and Ibn Sina (980–1037, called Avicenna), who moved among courts in Central Asia and Persia.

The education of both of these men included philosophy, metaphysics, astronomy, theology, mathematics, poetry and even practical engineering. As a result, their books on medicine often mixed cosmological causes with such empirical ones as the patient’s environment, temperament and lifestyle.

Such books, however, are only important if they lead to alleviation of suffering and the curing of illness, and in that regard, the Baghdad court and the elites of dozens of cities within the Islamic world sought new medicines from India simply because they worked. Turmeric, for example, has anti-bacterial properties that can stop the festering and promote the healing of wounds. If eaten, turmeric retains some of its anti-bacterial qualities inside the body. Regardless of the theories of humors, working doctors knew an effective remedy when they saw one. This empirical knowledge passed into medical books, and indeed a striking feature of Ibn Sina’s Canon, the most famous medical book of the age, is the sheer number of tropical plants and derivatives—some three dozen or more, many from India.

Such books, however, are only important if they lead to alleviation of suffering and the curing of illness, and in that regard, the Baghdad court and the elites of dozens of cities within the Islamic world sought new medicines from India simply because they worked. Turmeric, for example, has anti-bacterial properties that can stop the festering and promote the healing of wounds. If eaten, turmeric retains some of its anti-bacterial qualities inside the body. Regardless of the theories of humors, working doctors knew an effective remedy when they saw one. This empirical knowledge passed into medical books, and indeed a striking feature of Ibn Sina’s Canon, the most famous medical book of the age, is the sheer number of tropical plants and derivatives—some three dozen or more, many from India.

In the 13th century, a Latin translation of the Canon circulated from Italy north into Europe, where it became the principal medical text of the European Middle Ages. At about the same time, the Baghdad caliphate weakened, and as successor states emerged on its periphery in Central Asia, Persia and Afghanistan, physicians sought new positions in new courts. The Canon traveled with them and was translated into Persian and Urdu. In this way, Abbasid Baghdad did not represent a singular “Golden Age” after which there was only decline; rather, in the successor courts, doctors continued to write and develop new methods.

Following the Mughal conquest of northern India in the 16th century, the court of Delhi attracted many Muslim doctors. There, they came face-to-face with practitioners of the ancient Indian medical system known as Ayurveda, which they may have known previously by reputation or through translated texts.

|

| Plants form the basis of Unani treatments. Top-Left: This Unani formulary is written in Hindi. Top-Right/Above-Right: Loose herbs for compounding and syrups from herbs appear in an Unani pharmacy in Hyderabad, India. Above Left: The herb garden is a centerpiece of the Unani Medical College in Pune. |

Rooted in the Sanskrit word for “life science,” Ayurvedic medicine was by then already more than 1000 years old. While Muslim doctors would have found Ayurveda’s description of the body as composed of four elements and four humors familiar, Ayurveda’s emphasis on energy flows and energy centers (chakras) would have been new—as would have been Ayurveda’s encyclopedic selection of more than 1000 tropical plants compounded for medicines.

As a result, within a few decades of the Mughal conquest, several Ayurvedic medical texts had been translated into Arabic, and by the early 14th century, original medical treatises written in Arabic at the Mughal court routinely referred to local Ayurvedic medical practice and indigenous medicines. (In the other direction, some Greco–Islamic texts were translated into Sanskrit and Indian regional languages, too.) Both at the court of the Delhi Sultanate and those of later Muslim kingdoms of central and southern India, Muslim doctors worked alongside their Ayurvedic colleagues. This dialogue between Ayurvedic practice and what became Unani is encapsulated in an observation about himself made in 1590 by Muhammad Qasim Firishta, a historian and Muslim Ayurvedic practitioner:

After perusal of the books on the subject [medicine] commonly used in Iran, Turkey, and Arabia, his mind turned towards the study of the works of Indian physicians. He found their theories as well as their practice of medical science extremely well founded. He, therefore, thought it necessary to compile a book dealing with their medical principles and their application and with their system of treatment of diseases which at the outset appeared to be strange.

In these ways, each medical tradition learned from the other.

After 1707, the chaotic, at times violent, decline of the Mughal Empire presented practical dilemmas for court physicians. While some stayed, others sought patronage in the remaining Muslim kingdoms such as Oudh, Hyderabad and Mysore; still others moved to smaller kingdoms and towns across northern India, Bengal, central India, Gujarat and the Deccan. Indeed, the decline of the Mughal Empire resulted in the spread of what would soon be named “Unani” medicine across much of the subcontinent.

Until the late 18th century, Greco–Islamic medicine had been known in India simply by the Arabic word tibb (“medicine”). The earliest known references to the word “Unani” are in two late-18th-century medical treatises from Delhi: the Takmila-i Unani (Perfection of the Greek) and Mu’ali-jat al-Nabawi (Prophetic Treatments). In this same period, Indian doctors who emigrated west to the Ottoman Empire—of which Greece was then a province—were called “Unani.” In this short time, the term seems to have become synonymous with tibb.

|

| Map: Shutterstock |

In the second half of the 19th century, like their western counterparts, Unani doctors began to systematize their practices with colleges, examinations, diplomas, licenses, professional organizations and standardizations of medicines. These developed alongside and often in competition with the traditional apprenticeship system.

Unlike in western traditions, numbers of women were among students at the Unani medical colleges from the beginning. There had always been some female Unani practitioners, usually serving women who were secluded within households. Never before, however, had there been professionalization. This emerged partly under the patronage of several women leaders, such as the learned Begum of Bhopal, who ruled the central Indian state for more than 30 years at the end of the 19th century. The needs of women’s health and the availability of schools where women Unani doctors could be trained led to a rapid rise in the number of female practitioners, and even today the numbers of men and women at Unani colleges are roughly equal.

|

| Mark De Fraeye/Wellcome Images |

| At the government Nizamia Unani Hospital in Hyderabad, India, an arthritis patient receives treatment. Below-Right: An Indian postage stamp commemorated the 25th anniversary of the hospital's founding in 1938. |

|

| DBI Studio / Alamy |

In 1985, the Indian legislature formally recognized and funded Unani as part of the ayush cluster of five alternate medical systems: Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddi and Homeopathy. With government recognition came more Unani medical colleges, more doctors and broader public acceptance. For the past two decades, the Indian government’s Central Council of Indian Medicine has set the curriculum and standards for Unani medical colleges and funded the development and systematization of Unani medicine through a nationally recognized formulary published both in print and on-line. This database now includes the name of each plant both in Latin and in languages where it is known and used; its efficacy for various conditions; and contraindications and suggested dosages. The government has also funded regional Unani research centers, where formulas and promising plants are scientifically tested, and where the results are published in peer-reviewed journals and subjected to the same requirements of replication and statistical analysis used to establish western pharmaceuticals. Today, about 50,000 Unani doctors, supported by 41 medical colleges, work in India—a number 10 times greater than the number of licensed Ayurvedic doctors.

In Pakistan, where many Unani doctors moved following India’s partition in 1947, government recognition of Unani medicine and training dates back to 1965, when the government established a board to set standards for Unani, Ayurvedic and Homeopathic medicines, to register and license practitioners and to sponsor research. The Ministry of Health directly controls Unani medical colleges throughout the country, which educate about the same number of Unani doctors as India—50,000—but here they make up a more significant sector of health care, as they serve nearly a majority of patients requiring primary care in rural areas.

|

| Unani doctors take a patient's pulse in a way that resembles not only Ayurvedic but also Chinese methods. Each of the doctor’s fingers is placed in a position from which specific organs can be assessed. |

Modern Unani practice retains much of its long tradition, including the core idea of balance and the principle that treatment assists the body to heal itself. Plants provide the vast majority of Unani medicines. The doctor examines the patient’s pulse, eyes, urine and stool, and elicits details of family history and personal habits in order to tailor the treatment to the individual. Since the 1980’s and 1990’s, Unani has gained a reputation for efficacy in chronic illness that seem resistant to western medicines, particularly diseases of the digestive tract and high blood pressure. Patients are attracted to Unani doctors’ commitment to them as individuals, and to the doctor’s careful attention to medical history and situation.

Looked at in this light, Unani is more than merely the application to disease of a set of beliefs embodied in books: It is the fruit of a long, pragmatic search for cures, one that started millennia ago, crossed many lands and eras, and continues today. Even now, there are ongoing improvements in the delivery of Unani’s herbs, as medical supply houses now prepare most of the single-plant medicines and ship them to all parts of India and overseas, subject to testing and safety under government oversight.

In training, the apprentice system is gone, and entrance examinations are highly competitive. In India, most—but not all—of the students are Muslims. The five-year curriculum, in Urdu or English, includes state exams every 18 months and is followed by a one-year internship and the certification exam that only 60 to 70 percent pass on the first attempt. (Retakes are permitted, six months later.)

In training, the apprentice system is gone, and entrance examinations are highly competitive. In India, most—but not all—of the students are Muslims. The five-year curriculum, in Urdu or English, includes state exams every 18 months and is followed by a one-year internship and the certification exam that only 60 to 70 percent pass on the first attempt. (Retakes are permitted, six months later.)

As described by Rehan Safee, md, professor at the Unani Medical College in Pune, much of the Unani curriculum would seem familiar to medical students worldwide: The anatomy textbooks, for example, are current editions from the us. Dissection of cadavers is required. The library houses western and Unani medical references, in addition to many research journals, largely focused on the herbal formulations, which are emphasized as a first line of medical response. There is, Safee says, no illusion that Unani is always the best or an exclusive response to all medical situations: From automobile accident injuries to runaway infections, he says, many things are best done in a western-style hospital. Nevertheless, Unani has established the efficacy of its methods for chronic illnesses such as arthritis, high blood pressure, psoriasis, hepatitis and problems of the digestive tract.

|

| Students relax in the garden of the medical college in Pune. Since the 19th century, the number of women practitioners of Unani has roughly equaled the number of men. |

Among students at the college, some plan post-graduate degrees in medicine, pharmacology, surgery, gynecology or preventive medicine, planning to become teachers or researchers; others are headed for nursing homes, hospitals or the National Rural Health Mission. Like their western counterparts, only a few plan to open a family practice. Among all of them, says Arshad Pathan, md, who both teaches at the college and conducts a private practice, their patients are likely to be about 70 percent non-Muslim.

The students’ use of both Urdu and English in conversation and of both American and Indian textbooks is no mystery: It is a continuation of Unani’s millennia-old tradition of pragmatic adoption of the best of other medical systems, while retaining the herbal practices central to local tradition. Rigorous training in colleges like the Unani Medical College in Pune looks like a good prescription for Unani’s longevity.

|

Stewart Gordon is an independent scholar attached to the Center for South Asian Studies at the University of Michigan. His most recent book, When Asia was the World, has been translated into languages including Chinese, Korean and Arabic. Samples of his next book, A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks, can be found at www.stewartgordonhistorian.com. |