|

| CAROLINE STONE |

| Narcissi adorn this detail of a box from Kashmir painted in Mughal style. |

It is hard to imagine springtime in northern Europe, or much of the us, without the crocuses, tulips, narcissi, hyacinths and numerous other flowers that arrived from the Muslim world. It is almost as hard to imagine European cuisine without the fruits and vegetables of the Americas: potatoes, corn, peppers, tomatoes and squashes—to say nothing of chocolate, pineapples and vanilla.

|

| LEFT: STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, LEIDEN / WERNER FORMAN ARCHIVE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY; RIGHT: ALBUM / ART RESOURCE |

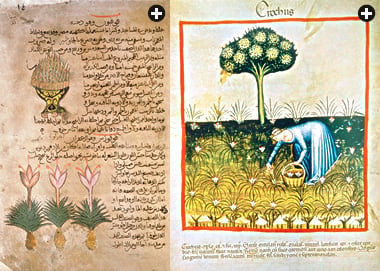

| Probably introduced to Europe in the 13th century, saffron crocuses have long held both medical and, most importantly, economic value. Crocus sativus appears on this folio, left, from a 10th-century Arabic version of Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica and in this 15th-century illustration, right, a woman harvests crocus blossoms for saffron. |

Plants both have moved and have been moved since time immemorial, but during Greek, Roman and Islamic classical periods, interest lay primarily in those of economic or medical importance. Purely decorative flowers were felt to have been of limited importance until the 16th century, although scented ones were considered health-giving and hence classed with herbal drugs.

Treatises, from Cato’s On Agriculture, written around 160 bce, to works on agriculture from botanists in al-Andalus and elsewhere in the Muslim world of the Middle Ages, tend to concentrate on these categories. Even Ibn Bassal, who collected plants in the late 11th century while returning to Spain from the Hajj, mentions few flowers for their beauty or rarity among the more than 180 listed in his Diwan al-Filaha (Book on Agriculture). This might seem surprising today, since he was head of the royal botanical gardens in Toledo, and later in Seville.

|

| SNARK / ART RESOURCE |

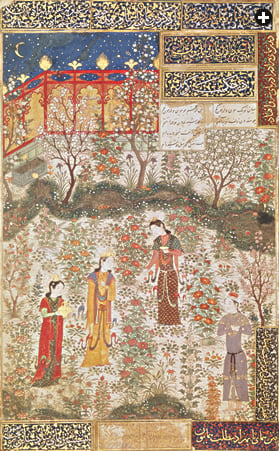

| This miniature, dated to around 1430, by a painter of the Herat school, illustrates a royal garden abundant in hollyhocks, which were particularly common in Central Asia and reached northern Europe about the 13th century. |

The first wave of plant introductions about which we have written records took place during the classical period. Alexander the Great, for example, is credited with bringing the lemon and the peach to Europe as a result of his Persian campaigns in the fourth century bce. Other citrus fruits were known around the Mediterranean, especially the citron and almost certainly the bitter—or “Seville”—orange. Agriculture declined after the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century ce, and many plants, including citrus, were introduced or reintroduced in the wake of the Muslim entry into Europe in the eighth century.

Another wave came during the Crusades. Once again, practical considerations seem to have been paramount. The English geographer Richard Hakluyt, writing in the 1580’s on the value of plant introductions, relates how a pilgrim “purposing to do good to his country” risked his life by smuggling saffron crocus bulbs back to England in his staff—an echo of the tale of the monks who allegedly smuggled silkworm cocoons from China to Byzantium in the sixth century ce.

The crocus, which now carpets northern European gardens in spring, appears to have arrived in England in the mid-13th century. Its name comes from the Aramaic kurkama, and it is native to the Mediterranean and Eurasia.

The Crocus sativus was almost certainly domesticated in Crete, where it has been cultivated for saffron for at least 3000 years. Saffron was so valuable as a spice, medicine and dye that rules against adulteration appear in nearly every code dealing with quality control. The significance of the crocus lay not in its beauty, but in its value as a cash crop.

Another plant that seems to have reached England in the mid-13th century is the hollyhock. Long synonymous with traditional cottage gardens, it is native to Eurasia. A number of species come from Central Asia, and they appear in the background of many miniature paintings, particularly those of the Herat school of the mid-15th century. (See illustration, above.) The name is thought to derive from “Holy Hoc,” or “holy mallow,” because it came from Palestine. Like many of the family, including marsh mallow and the popular Egyptian and Tunisian vegetable mulukhiyya, the hollyhock was held to have medicinal properties, and was probably introduced for that reason.

England had its own rose—Rosa canina—when the beautiful and highly scented Rosa damascena reached its shores in the 13th century, probably from Syria, where it had been an important cash crop for centuries. Syrian naturalist al-Dimashqi, writing around 1300, discusses it purely in economic terms as the key ingredient in making “the celebrated rose-water of Damascus.”

England had its own rose—Rosa canina—when the beautiful and highly scented Rosa damascena reached its shores in the 13th century, probably from Syria, where it had been an important cash crop for centuries. Syrian naturalist al-Dimashqi, writing around 1300, discusses it purely in economic terms as the key ingredient in making “the celebrated rose-water of Damascus.”

It was horticulturalists in the Far East who had long practiced selective breeding to increase the varieties of decorative plants. Their attitude seems to have percolated west into both the Muslim world and Europe by about 1500. Babur, founder in the early 16th century of the Mughal Empire in India and a passionate lover of nature and creator of gardens, adored tulips. He wrote in 1504-5 of the Kabul region—located within the center of diversity for the tulip genus:

|

| bridgeman art library |

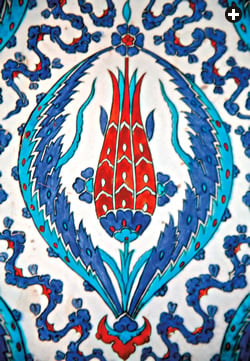

| A stylized tulip adorns a tile in Istanbul’s Rüstem Pasha mosque, completed in 1563. With many species originating in Central Asia, the tulip became one of Ottoman Turkey’s most popular flowers and artistic motifs. |

Tulips of many colors cover these foothills; I once counted them up; it came out at 32 or 33 different sorts. We named one the Rose-scented, because its perfume was a little like that of the red rose; it grows by itself on Shaikh’s-plain, here and nowhere else. The Hundred-leaved tulip is another; this grows, also by itself, at the outlet of the Ghur-bund narrows, on the hill-skirt below Parwan.

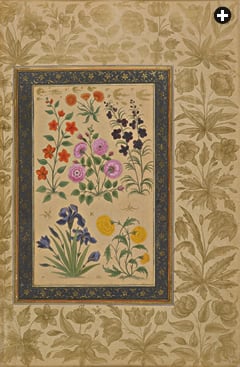

Later, Babur would try to introduce to India numerous plants from his homeland of Uzbekistan as well as from Kashmir. Some of these appear in Mughal miniatures, and they also became decorative motifs in embroideries, textiles, carpets and furniture, as well as carving and inlay.

The passion for tulips in their many varieties spread westward by way of Iran and the Ottoman Empire, which experienced a period of intense interest in flowers and gardens in the 16th century. Tulips, hyacinths, roses and carnations were the favorites, together with narcissus and blossoms. Tulips are represented over and over again, on countless tiles, on the famous ceramics from Iznik, in the decorative paintings in palaces, on the lacquer covers of manuscripts and in textiles—from silk velvets to embroidered muslin scarves. There are even tulips all the way up the minaret of a recently restored 18th-century mosque built at the height of the Lâle Devri (Tulip Period) in Durrës, Albania.

|

| the british library |

| Produced in the 1630’s for Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, this folio elegantly depicts several flowers of Central Asia and Kashmir including several that were also introduced into Europe: roses, irises, delphiniums and what may be Asian marigolds. |

The 17th-century Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi describes the gardeners’ guild in Turkey and makes numerous mentions of flowers and their uses. Scented ones, for example, were placed in mosques, and great trays of them accompanied the procession when the Hajj caravan to Makkah set out from Istanbul. He also describes the Edirne gardens at the palace of Suleiman the Magnificent: They “cannot be equaled by any other garden on earth, not even that in the imperial city of Vienna in the lands of the Germans.” Its list of flowers includes “Chinese hyacinth.”

Although the greater migration of flowers west from China did not begin until the mid-18th century, a treatise entitled Tuhfe-i Çerağan (The Excellence of Festivals), written in the early 18th century during the reign of Sultan Ahmed iii, gives an idea of how nocturnal flower-viewing festivals by lamplight came from China with returning embassies.

Above all, however, information on various flowers comes from beautifully illustrated treatises, some of the finest examples of which are preserved in the library at Topkapı in Istanbul. A Sümbülname (Hyacinth book), dating from about 1736, illustrates 42 varieties. (Ironically, judging by their names, one or two had come back to the Ottoman world from Holland.) Other albums give detailed information on the provenance of the flowers, their cultivation and often notes on major plant breeders and collectors, as well as the names of famous bulbs and their owners, and even prices.

“The narcissus came from Algeria. It was first sown here by Ahmed Çelebi,” writes Abdullah Efendi in Sükûfenamesi, a 17th-century treatise on narcissi. He goes on to describe varieties and their cultivation, illustrating dozens. This contrasts with earlier writers, who offered much sketchier information. For example, the Persian traveler Nasr-i Khusraw writes of his journey on the coast road from Hama to Damascus in 1047 that “we came to a plain that everywhere was covered with narcissus flowers in bloom, and the whole plain appeared white thereby,” yet he provides no further details. And Ibn Bassal only mentions “white narcissus,” “yellow narcissus” and “jonquil” in Spain, even though it was a center of diversity for narcissi.

![“THERE WERE THOSE WHO HAD FLOWERS IMPORTED WITH THE GREATEST DIFFICULTY FROM INDIA, FROM MAGHRIB AND ALGERIA, AND FROM DISTANT EUROPEAN COUNTRIES, AND WHO SPENT ALL THEIR TIME BREEDING AND CULTIVATING FLOWERS…. [I]N SOME ACCOUNTS IT IS RECORDED THAT THE NUMBER OF VARIETIES AND KINDS OF TULIP REACHED 481 OF WHICH 149 ALONE WERE FROM CRETE AND CYPRUS.”

��–Abdülaziz Bey, c. 1900, cited in Nurhan Atasoy,�A Garden for the Sultan, 2002](images/flowers/inset-2.png) England has its own native wild daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus), made famous by Wordsworth, but by the 16th century, gardeners were on the lookout for new varieties. John Tradescant, a noted horticulturalist, writes in one of his plant lists:

England has its own native wild daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus), made famous by Wordsworth, but by the 16th century, gardeners were on the lookout for new varieties. John Tradescant, a noted horticulturalist, writes in one of his plant lists:

Reseved in the yeare 1630 from forrin partes. From Constantinople Sr Peter Wyche [the British ambassador]:

….On narciss

On ciclaman

4 renuncculuses

Tulippe Caffa

Tulippe perse

4 sortes of Anemones….

|

| caroline stone |

| The popularity of tulips, both as flowers and as motifs, spread west and north from Turkey. In Durrës, Albania, this 18th-century minaret is adorned with tulips. |

Two years later, he received hyacinths, tulips and several kinds of narcissus, including “Narcissus Constantinopolis,” which was probably Narcissus tazetta, the variety admired by Nasir-i Khusraw.

There are books on carnations and other flowers, but roses and, of course, tulips, were by far the most popular. According to an 18th-century treatise, it was Ebüssuud Efendi, the chief judge under Suleiman the Magnificent, who was responsible for the popularization of tulips. For instance, when he was given a white tulip—probably a spontaneous mutation discovered growing wild in Turkey’s Bolu region—he propagated it in his garden.

Another Sükûfenamesi, by Fenni Çelebi, provides extensive information about the “Cretan tulips” collected and propagated by Mehmed Aga, perhaps to while away the 21-year siege of Candia (Heraklion) in Crete—the longest siege in history. The Venetian-ruled city finally fell to Ottoman forces in 1669, whereupon he was able to take his flower collection safely home to Istanbul.

By the 16th century, the passion for new and exotic varieties of flora had taken firm root in Europe, and flowers like tulips were actively sought out for their aesthetic rather than practical qualities.

|

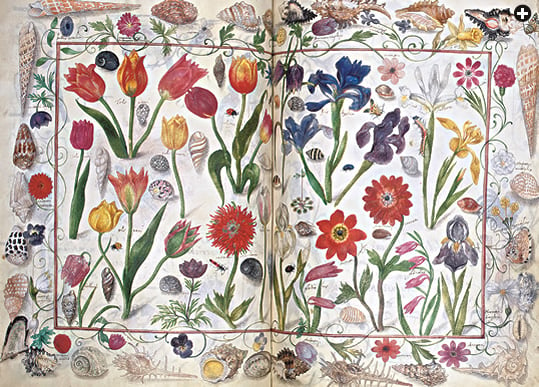

| christie’s images / bridgeman art library |

| An illustration from the 17th-century German Album Amicorum (Album of Friendship) shows a number of flowers introduced from the East including tulips, irises, anemones, a fritillary, wild gladiolus, and more. |

There is some debate about how the tulip got its name and how it arrived in Europe. In 1546, French naturalist Pierre Belon set off on a scientific journey through Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt, Syria and Palestine, and he published his Observations in 1553. He comments that it was the fashion for Turks to wear tulips in their turbans, or tülbend, which the tulips themselves at least vaguely resembled. Since the Turkish word for tulip is lâle, it has been suggested that the modern English name is the result of confusing the headdress for the flower.

There is no evidence, however, that Belon sent tulip bulbs home. A plausible theory is that the Austrian diplomat Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq gave some to his friend Carolus Clusius, the Flemish botanist in charge of the imperial medical garden at Vienna. De Busbecq was ambassador at the court of Suleiman the Magnificent, and he spent part of each year from 1554 to 1562 in Istanbul. Besides tulips, he is credited with sending home a number of other bulbs and plants, among them lilac, the grape hyacinth and the plane tree, to friends in Vienna and elsewhere. Later in his career, Clusius moved to Leiden, where he founded one of the first academic botanical gardens in Europe. From these transmissions sprang the extraordinary phenomenon of “tulipomania” in Holland in the 1630’s and the multimillion-dollar export industry of today.

|

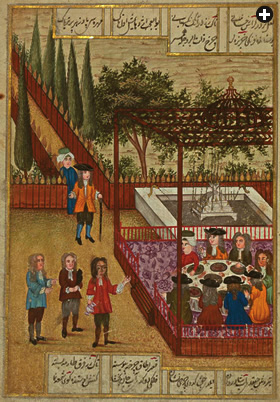

| walters art museum |

| This miniature shows Europeans dining in a garden with two Turks. Such an occasion might have led to a gift of flowers, seeds or bulbs or advice on where they could be purchased. |

Massive demand for bulbs was nothing new, however. In A Garden for the Sultan (2002), Nurhan Atasoy cites ledgers from Topkapı showing, for example, that in 1592 there was an urgent request for 50,000 white and 50,000 blue hyacinths from the summer pastures at Maraş in south-central Turkey.

Diplomats and merchants were important in the transmission of garden flowers back to Europe. They were in contact with the kinds of people who collected plants, who had gardens, and who also would have known where to obtain specimens. Clusius mentions that he saw the first scilla (Scilla siberica) in bloom in Vienna in 1575, grown from bulbs given to him by a member of the imperial delegation to the Ottoman Porte. Today, scilla provide a carpet of brilliant blue in northern gardens in early spring.

It is not clear whether lilies are native to western Europe, but the Madonna lily (Lilium candidum), which originated in the Balkans and western Asia, was certainly present as far back as classical times. As the name indicates, it came to have great symbolic importance through its association with purity and virtue.

Other varieties of lilies came along the route from Constantinople. The spectacular Crown Imperial (Fritillaria imperialis) is native to the area stretching from Kurdistan to the foothills of the Himalayas, where the red version was used for dye. It is the subject of numerous legends and a common motif in miniatures and embroidery. Clusius received bulbs forwarded from the Ottoman Empire to Vienna in 1576, and soon it was the “must have” in elegant gardens, although it is relatively little grown today. The yellow variant—lutea—was first mentioned in 1665.

One more 16th-century introduction, probably along the same route, is the Turk’s Cap Lily—Lilium martagon. It grows across Eurasia, but there is some debate as to whether it is also native to certain areas of Europe. The word martagan, meaning a small, tightly rolled turban in Turkish, suggests that, wherever it may grow, it reached Europe from the Ottoman world. It appears in English in the 16th century and is apparently mentioned as growing in Bergen, Norway, by 1597, which gives an idea of how quickly fashionable plants spread.

Lilac (Syringa vulgaris), another important symbol of spring across eastern Europe, is native to the Balkans, but because of religious and political divisions, it reached western Europe from the gardens of Constantinople from two directions: De Busbecq carried it to Vienna, while the Venetian ambassador introduced it to Italy.

Lilac (Syringa vulgaris), another important symbol of spring across eastern Europe, is native to the Balkans, but because of religious and political divisions, it reached western Europe from the gardens of Constantinople from two directions: De Busbecq carried it to Vienna, while the Venetian ambassador introduced it to Italy.

Sir Thomas Roe, the English ambassador to both the Mughal and the Ottoman courts in the early 17th century, sent home plants at the request of John Tradescant, head gardener to various members of the nobility, including George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, and King Charles i.

This was a period marked by great competition to produce the finest gardens with the most unusual plants. Buckingham asked merchants in the Levant to send him any exotic and unusual flowers they could acquire. It is not surprising, therefore, that Tradescant was sent on missions to the Netherlands, from which he introduced a number of plants that had arrived from the Middle East. He also went on an expedition to Russia, and from there he brought back new species, including the larch and a type of pink that was apparently highly scented. (Sadly, Tradescant could not vouch for this himself: He had no sense of smell.)

Pinks had symbolic importance in Europe, and they appear in many paintings and in the borders of manuscripts, but always as small, flat flowers with five petals. The richly frilled carnations beloved of the Ottomans were clearly different and almost certainly cultivated, probably as a hybrid from the Mediterranean Dianthus caryophyllus, since there are no wild progenitors. These pinks reached England from Constantinople in the mid-16th century and seem to have been double-flowered, scarlet and with the characteristic clove scent.

|

| private collection / caroline stone |

| This illustrated album of Persian poetry dates from the early 18th century, and this folio shows a damask rose set among a spray of fruit blossom, violets and a scilla. |

Selective carnation breeding began both in Ottoman gardens and in the West. By the early 1600’s there were dozens of varieties—one English list mentions 63, and the Turkish Karanfil Risalesi (Carnation Treatise) illustrates some that were to provide the ancestors for the modern carnation, which is today perhaps the most widely sold flower in the world.

Taking advantage of the opportunity for further travel, in 1620 Tradescant volunteered for an expedition against the corsairs of Algiers. The expedition was not a success, but he managed to go ashore near Tétouan, Morocco, writing “that he saw many acres of ground in Barbary spread over with the Corne Flagge or Gladiolus.” Even into the late 20th century, fields of the bright magenta Gladiolus byzantinus were still a spectacular sight in North Africa.

The gladiolus family largely grows south of the Sahara, but this species, which adapted well to the north, quickly became popular, and it is the ancestor of the much larger garden gladiolus today. Surprisingly, it does not seem to have attracted attention among gardeners and artists in the Islamic world, perhaps because it was associated not with gardens but with agriculture—as a weed! Other spoils from this expedition included the “Algiers apricot,” a variety superior to that known in England at the time, and the wild pomegranate (the cultivated variety was already known) “of an excellent bright crimson color, tending to a silken carnation,” Tradescant writes.

During much of this time, all of these plants from the East were also moving even farther west, carried by enterprising horticulturalists across the Atlantic to North and South America, and often naturalized there. By the middle of the 18th century, flowers that had been the pride of gardens in Constantinople, Aleppo, Vienna and Leiden were becoming commonplace in Alexandria, Virginia, and nearby Georgetown.

|

Caroline Stone (stonelunde@hotmail.com) divides her time between Cambridge and Seville. Her latest book, Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness, translated with Paul Lunde from the medieval Arab accounts of the lands in the Far North, was published in 2011 by Penguin Classics. |