It’s a few minutes after sunup and the old charter plane is completing its descent into Faya Largeau, the largest of the sparse oases of northern Chad. The southern Sahara below shifts from a dark moonscape to reveal the first impression of dunes, just perceptibly orange; then singles, then clusters, then forests of date palms appear as the plane comes in to land.

ahamat Souleymane, the head of airport security, takes a look at the surname in my passport and smiles broadly. He emphasizes the double meaning when he says, “Welcome to Chad,” and repeats it.

ahamat Souleymane, the head of airport security, takes a look at the surname in my passport and smiles broadly. He emphasizes the double meaning when he says, “Welcome to Chad,” and repeats it.

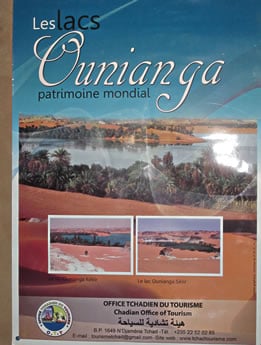

I’m in this Central African country to explore Saharan climate history through the lens of one of the Earth’s great geological anomalies—the Lakes of Ounianga (oo-nee-ahn-ga). In 2012, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (unesco) added these 18 interconnected, freshwater, saline and hyper-saline lakes to its list of World Heritage sites.

“Every lake tells its own story,” says Columbia University marine geologist Peter deMenocal, whose research underpins much current thinking about the climate history of the Sahara. So what stories can be found on nearly a score of lakes that are apparently environmentally far out of place: in the deepest desert, more than 800 kilometers (500 mi) from the nearest other lake, Lake Chad? There are two men on this expedition who have spent much time searching and probing for these stories, and one of them is waiting with three 4x4 vehicles to make the daylong trek to the lakes. He is Baba Mallah, president of the scientific committee in charge of Chad’s unesco bids and the nation’s leading scientist.

|

| Geoarcheologist and veteran of four decades of eastern Sahara research, Stefan Kröpelin is studying year-by-year lake-bottom sediment from Ounianga to model exactly how and when the savannah dried into today’s Sahara. |

Bounding up to Baba (in Chad, first names are customary) is the other man, Stefan Kröpelin, a veteran geoarcheologist from the University of Köln, Germany, who has plied the eastern Sahara for four decades and carried out research in Ounianga since 1999.

Baba’s ordre de mission is to work with Kröpelin to update unesco with a scientific review of the lakes, and perhaps delight it with some new discoveries. Baba is eager to show me “the unheard-of geology of the desert. We have everything there—natural beauty and mystery—but it also is our wealth. Chadians love our deserts like others love their forests.”

After repairing a roof-rack to carry our luggage along with a sheep for dinner, we climb into a Land Cruiser and take off on a dirt track, used barely once a month, that extends all the way to our destination: Ounianga Kebir (“Big Ounianga”). Kröpelin jokingly refers to it as “Highway One.” Our driver, Abdulrahim, senses whenever the ground gives way to soft sand, and he downshifts, outside the old tire tracks. Constantly.

The desert colors change every time I turn my head. Here, a lone tree miraculously survives. There, a “trapping stone” used by our distant ancestors to funnel animals toward their deaths and give our species life. We’re close to where the Iron Age started. We’re also close to where we started: In a desert not too far away in 2001 and 2002, fossils, including a partial skull, were found that were named Toumai, which means “hope of life” in the Goran language of this region. Dating back seven million years, Toumai is to date the oldest known hominid, the closest we have come to the point of divergence that led to chimpanzees and humans. It was Baba who gave Toumai his scientific name: Sahelanthropus tchadensis.

An hour before sunset, we stop for the night close to the slip-face of a massive, arch-shaped barchan dune, which will protect us from the wind in the night. Bright orange sand reaches up 100 meters (320'), and a single dune could contain some 200,000 tons of pure quartzite. Like hundreds of thousands of similar dunes throughout the Sahara, it was formed from the sands of the Mediterranean Sea, and, as if they were a flock of birds, they have been migrating south with the harmattan trade winds some eight meters (25½') a year for the past few thousands of years. So far, this dune has advanced some 2400 kilometers (1500 miles).

That night, sitting on a carpet under the starry sky, we eat mutton. The multilingual conversation includes Chadian Arabic—almost universally spoken throughout the country—Goran, the language of the north, French, English and German.

|

| “There are salt lakes in deserts worldwide, but freshwater lakes you just don’t have,” says Baba Mallah, physicist and director of Chad’s national scientific research center. Standing on the shore of the reed-covered portion of Lake Boukou, he explains that the reeds retard evaporation, and together with replenishing seepage from the aquifer below, the lake water stays fresh. |

Baba, a physicist by training, is a polymath scientist, having headed the National Center for the Support of Science, which oversees all of Chad’s research, for 17 years. In 2012 he became the director-general of the Petroleum Institute. By descent, he is from the royal line of the Kanem-Burnu, who in the 11th century brought Islam to Central Africa.

Baba has been coming to the Lakes of Ounianga since he was a child. His village was in Kanem, the closest region south of them. Those who went north were called Toubou, “the brothers from the south,” and those who stayed were Kanembu, “the brothers of the people of the mountains,” he says.

As the evening deepens, Mahmoud Younous, director-general of the Chad Office of Tourism, toys with the star-rating system of hotels by calling our duneside bivouac “le hotel de milles étoiles”—“the hotel of a thousand stars.” He is, in fact, understating by millions. Night in the Sahara is an elemental experience.

On the road early the next morning, we pass sandstone table rocks or massifs. Other formations are needle-, pyramid- or Sphinx-shaped yardangs, aerodynamically sculpted by the harmattan over millions of years.

Then we come across camels, grazing on grasses and herbs in a desert that should be devoid of vegetation. The car tops a rise, and even though I knew it was coming, the vista steals my breath. In the depression below the escarpments at the edges of Ounianga Kebir is a mirage come to life: Lush green foliage and cerulean lakes. Squinting through the dust carried by the wind only makes the sight more surreal. All through our stay here, I hear the wind—touch it, feel it and even smell it.

For the Chadians, another wonder has seized their attention: Cellphone coverage. There is a tower nearby, and now everybody in the expedition is calling and text- ing back home to N’Djamena, the capital.

The sun is setting as we tour our first lake, Uma, in Ounianga Kebir, which is comprised of four lakes. A man is leisurely dousing himself just off the sandbar that splits this salt lake. The water color is red, an effect of the algae Spirulina platensis, which covers the lake in a layer as thick as 15 centimeters (4") in places. It stinks. This, Kröpelin explains, means there has been little wind for a few weeks prior to our arrival. “If there is wind, they don’t smell,” he says. But neither the smell, nor the sight of a man swimming in the Sahara, astounds nearly as much as the croaking of a frog.

It’s a living reminder of the era of the Green Sahara, known as the African Humid Period, which lasted roughly from 11,000 to 5000 years ago, but here at Ounianga, it is still, in effect, going on. This frog is a survivor, a biological relic of the once-vibrant life of the North African savannah—now the scorching Sahara—where elephants, giraffe, hippos, antelopes and a wild ancestor of domestic cattle called aurochs once made their homes.

e make our campsite on the hillside above Lake Boukou, in the second cluster of lakes, called Ounianga Serir (“Little Ounianga”), about 50 kilometers (30 mi) east of the Ounianga Kebir lakes. Boukou is a freshwater lake, surrounded by palms and colored deep blue, half-covered by green reeds that somehow complement the Martian landscape of massifs and drifting dunes.

e make our campsite on the hillside above Lake Boukou, in the second cluster of lakes, called Ounianga Serir (“Little Ounianga”), about 50 kilometers (30 mi) east of the Ounianga Kebir lakes. Boukou is a freshwater lake, surrounded by palms and colored deep blue, half-covered by green reeds that somehow complement the Martian landscape of massifs and drifting dunes.

We camp in the open, and at three a.m. I’m startled by five jackals surrounding my head, a meter away. It’s as if they are debating which part of me each one might grab first. I scare them off, go back to sleep and later wake to a glorious sunrise. All is silence. The orange sands, the massifs, the lake: All shimmer in the morning sun.

On the walk down to the shore, I’m distracted from that beauty by what’s underfoot. Stone hammers, scrapers and other tools are strewn about here, some dating from half a million years ago to “new ones” from the Neolithic era “only” 5000 to 10,000 years ago. I meet Baba, his shortwave radio pressed to his ear, listening to the news, beside what looks like a field of wild grasses, but it’s actually the reed bed on top of part of the lake.

|

| Away from the reeds, the fresh water of Lake Boukou is both pleasing to the eye and habitable to aquatic life, below right. |

“There are salt lakes in deserts worldwide, but freshwater lakes you just don’t have,” says Baba.

The Sahara is the largest of the world’s hot deserts. (The polar regions are deserts, too, and larger.) The sun here is so intense that the record measured evaporation rate at nearby Lake Yoan was enough to lower the water level by six meters (19') a year. Yet now, and presumably during the last 3000 years of hyper-aridity, rainfall has been measured only in millimeters a year. Properly, any lake here “should become like the sea with the highest density of salt,” says Baba, or it should have long ago disappeared completely.

“But in Ounianga we have this very big freshwater lake,” says Baba, beaming so warmly at the paradox that his smile could accelerate the evaporation process.

Baba points to the Phragmites and Typha, the reed genera growing up to six meters, floating on their own debris in the 20-meter-deep (65½') lake. “Here, the sun doesn’t hit directly the water,” he explains. “The evaporation rate is very low, so the water is just about perfectly fresh.” Plentiful fish and crustaceans testify to his point.

What we see here, he explains, is the result of a hydrological system, unique in the world, that keeps all but one of the 11 lakes of Ounianga Serir fresh. To understand more, we go on a tour to the central Lake Tili. And, yet again, we have to step back in time.

uring the wet millennia of the Humid Period, water accumulated in what is now the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, which underlies much of the eastern Sahara. This is the world’s largest fossil-water aquifer, and it spreads roughly two million square kilometers (772,000 sq mi) beneath Chad, Sudan, Egypt and Libya to a maximum depth of 4000 meters (12,800'). The Lakes of Ounianga are supplied from below by this aquifer, which has allowed them to survive the climatic changes so far.

uring the wet millennia of the Humid Period, water accumulated in what is now the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, which underlies much of the eastern Sahara. This is the world’s largest fossil-water aquifer, and it spreads roughly two million square kilometers (772,000 sq mi) beneath Chad, Sudan, Egypt and Libya to a maximum depth of 4000 meters (12,800'). The Lakes of Ounianga are supplied from below by this aquifer, which has allowed them to survive the climatic changes so far.

Remember, however, our barchan dunes. Slow but relentless, they have coalesced into “megabarchans,” corridors of dunes that extend for hundreds of kilometers. Long ago, they moved into the two big original lakes in Ounianga Kebir and Ounianga Serir, splitting them into the clusters of smaller lakes we see today.

As we pass in the Land Cruiser, it is easy to see how the elongated dunes separate the lakes in the basin, an action that continues, and that may, in time, obliterate them.

|

| Leaders of two of northern Chad’s most remote communities, Aahmat Moussa Thozi, middle, of Ounianga Kebir, and Nebi Guett, right, of Ounianga Serir, link their legendary tribal histories to today’s science. “There was a very ancient population that lived next to this lake. We believe that our grandfather came out of the lake,” says Thozi. Not far from here, the 2001 and 2002 Toumai skull discoveries show that hominid and human habitation in this region may date back seven million years. Right and below: The Office Tchadien du Tourisme, for which Ahamadai Barkai is a coordinator in the Ounianga Lakes region, promotes adventure travel to the lakes that Guett says have “become a source of pride, and we plan for a bright future.” (Note: In the print edition, Ahamadai Barkai was incorrectly identified.) |

|

From the settlement at Ounianga Serir, one of the world’s most remote, we take in the view of Lake Tili. It doesn’t have the mats of reeds that cover the surface of the fresh lakes. Also in contrast to them, Tili’s rapid evaporation rate makes it hyper-saline and keeps its depth to only two to three meters (6 to 9½'); its surface elevation is the lowest of all the lakes.

The difference in elevation drains a slow flow of water into Lake Tili from adjacent lakes through the semipermeable dunes. This “evaporation pump” causes the other lakes to draw continually from the aquifer below to replace their own losses. Together with depth and the partial reed covers, this replenishment works to keep the water in the other lakes fresh.

Yet what we see today is but a remnant of the two vast lakes that once fed south into the largest inland lake ever known to have existed on Earth: the Mega-Chad, once larger than today’s Caspian Sea.

ur mission,” says Baba, “is to sample diatomite to see how the lake levels have changed during the different periods.”

ur mission,” says Baba, “is to sample diatomite to see how the lake levels have changed during the different periods.”

Diatomite is a light soil made up of the microscopic skeletal remains of diatoms, single-celled plants that have sunk to the bottom of lakes and oceans. When the water of a lake recedes, diatomaceous earth can often be found on the walls of the sandstone escarpments that surround the lake basin. It can be sampled, the elevation of deposits noted, and then it can be carbon-dated. By adding the approximate depth of the lake, and using a “virtual flooding” computer model, you can, in theory, pro-ject the extent of the “paleolakes” during each time period.

Kröpelin makes his way around a palm grove near Lake Edem in Ounianga Serir and up a steep gully of the sandstone escarpment that in the Humid Period must have had a rivulet. He reaches a jutting ledge that offers a view of Edem, which is completely covered by reeds.

|

| “With Stefan Kröpelin [right], we’re in debt,” says Baba, left. “We are able to understand precisely how these lakes function,” he says. “Naturally, if we had the means, we’d do [the coring and analysis] here, and it would be uniquely a Chadian discovery.” In Baba, says Kröpelin, “I have a decade-long friend and trust.” |

Kröpelin takes notes, and then takes out his geologist’s hammer to chip out diatomite specimens. “I’m the first geologist since the origin of Earth to take a sample at this site,” says Kröpelin. He scrapes away the crust. The sediment does not resist. He digs his hand into the hole he has dug and pulls out the diatomaceous earth in white chunks. They’re fragile. They crunch easily in his hand.

Without carbon dating, it’s hard to be sure of their age, but he guesses they will prove to be “younger than 6000 to 7000 years old.” Other samples have dated to between 8500 and 9500 years ago. His altimeter reads 405 meters (1300') above sea level, plus or minus 10 meters.

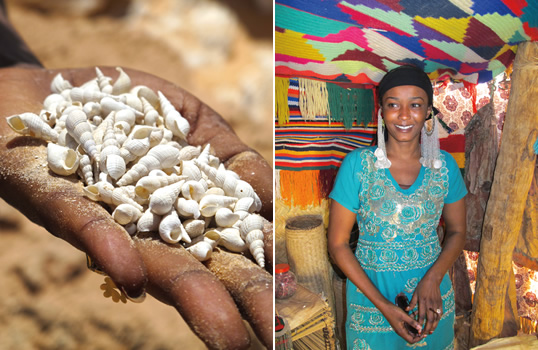

Less scientifically, but with no less enthusiasm, Fati Dadi, from the tourism office, brings Kröpelin a handful of sun-bleached mollusk shells she has chipped from another part of the ancient lake sediment. “I am making necklaces,” she explains. “I take a needle and I pierce some holes. C’est originale?” Kröpelin smiles. “Ten thousand years old,” he says. “You can’t buy that.”

Back near Lake Boukou, we pass a train of camels, and shortly afterward, our smaller caravan of three Land Cruisers stops at the water’s edge. We get out and, though the heat of the day is finally breaking, the lure of a freshwater swim has one, then another and another of the crew plunging into the lake. Kröpelin’s last dip here left him with schistosomiasis, the waterborne, parasitic disease that frequently infects tropical waters. Yet in true desert-adventurer style, he declares “No risk, no fun!” and dives in, too. (Four months later, he reports he has to repeat the treatments.)

t Yoan, the largest lake in Ounianga Kebir, huge drifts of sand blow down to the edge of the deep-green water. A group of Toubous, men of the local ethnic group, take shade beneath palm trees that look as if they had been placed by a landscape designer. I realize one of the men is Baba. I join him and ask him where he is more at home, in the desert or in the laboratory?

t Yoan, the largest lake in Ounianga Kebir, huge drifts of sand blow down to the edge of the deep-green water. A group of Toubous, men of the local ethnic group, take shade beneath palm trees that look as if they had been placed by a landscape designer. I realize one of the men is Baba. I join him and ask him where he is more at home, in the desert or in the laboratory?

“Sincerely, I’d rather be in the laboratory. It’s where my joy is,” says soft-spoken Baba. But then he catches himself. “I think they are complementary. I love the desert, but I would love the possibility to submit the results from the desert in the appropriate laboratory where I can participate. But that’s the problem,” he continues. “Today, in Chad, institutes and universities have been created, and we have formed a knowledge-based elite, a core group of researchers, but we have not the laboratories.”

|

| With reed-carpeted Lake Edem in Ounianga Serir in the background, sun-bleached and brown sandstone that once lay submerged offers samples of fossil microorganisms that, when carbon-dated, yield evidence of the lake’s extent at different times. |

As we speak, a few Chadian members of the expedition’s support staff fill plastic bottles with the natural salt foam that gathers on the shore of the hyper-saline lake. Kröpelin later explains that it’s natural salt foam. “You can eat it,” he says, adding that Chadians regard it as a health tonic.

What lies under the waters of Lake Yoan, however, is what may offer the Ouniangas’ greatest potential contribution to science: “The long core.” Kröpelin speaks the term in a tone normally reserved for legends and elusive treasures.

For decades, Kröpelin had been looking at thousands of now-dry paleolakes throughout Sudan, Egypt and Libya in his search to reconstruct the environmental and climatological history of the eastern Sahara. His results were limited because all the lakes dried up so long ago. ”We had nothing for the past 4000 years,” he says.

His hope was to find an ongoing accumulation of deposits, something that is only possible in a present-day body of water.

|

| Holding shells, souvenirs of the African Humid Period from 11,000 to 5000 years ago, Fati Dadi of the office of tourism says she will string them into a necklace. |

In 1999, Kröpelin got to Lake Yoan, and he used a gravity corer to excavate half a meter (1½') of lake-bottom sediment. It was a test—and the find of a lifetime.

“There could have been nothing. It could have been sand. It could have been homogenous mud where you couldn’t do anything,” Kröpelin remembers. But it wasn’t. Clearly layered with sub-annual laminations, the core showed it was possible to analyze its layers of deposits not just yearly, but even seasonally.

“So it was clear this was worth a big coring campaign.”

He returned in 2004 to extract a 6.5-meter (21') core that showed a continuous paleo-environmental record of the past 6000 years. Analysis of that long, thin column convinced Kröpelin that the prevailing scientific understanding of the most consequential African Holocene climate event—the demise of the Green Sahara—“was wrong from the beginning.”

Citing analysis of pollen in the sediments of the core, in a 2008 research paper Kröpelin challenged the hypothesis, advanced by deMenocal, that North Africa dried from savannah to desert over the course of only a few centuries. The new data, Kröpelin asserted, was evidence that it may have been a far longer, much more gradual process, one taking not centuries but millennia.

This is more than an academic question. Accuracy in Saharan climate history research is important to today’s climate modelers who believe that the better they “tune their models” to history, the better they can project present-day climate changes into the future.

Kröpelin’s analysis, comments deMenocal, is “extremely important,” but geographically, he observes, it remains but a single “data point.” In contrast, he says, “there are about 20 other different data points from West and East Africa, and most recently in the Horn of Africa, that all look the same: They all get abruptly drier after about 5000 years ago. So which one was it? Or maybe it was both?” he adds. “To be honest, I would say we don’t know yet.”

n the town hall of Ounianga Kebir, I meet Aahmat Moussa Thozi, the chef de canton. The scientists are not the only ones interested in history. Through a translator, Aahmat tells me the legend of his tribe’s origins.

n the town hall of Ounianga Kebir, I meet Aahmat Moussa Thozi, the chef de canton. The scientists are not the only ones interested in history. Through a translator, Aahmat tells me the legend of his tribe’s origins.

“There was a very ancient population that lived next to this lake. We believe that our grandfather came out of the lake. The people who came out of the lake are linked to that lake. These localities were very beautiful, with palms, dates and a glorious lake. There are 15 clans in Ounianga. That is how it started.”

Are there cultural clues here to geological history? It would take a geo-mythological examination to know for sure. What exactly does “ancient” mean in a land where, over the seven million years since Toumai lived here, the African Humid Period was only the most recent of what may have been hundreds of wet phases. The recent one is of interest today only because it affected anatomically modern humans, and it is the one that may offer clues about our own future.

Aahmat continues, “My family came out of the lake. I am the offspring of that.”

His meaning: The lake gave his tribe life. But exactly when that was is another question, perhaps one for science.

|

| Men relax in morning shade at Lake Yoan, the largest of the Ounianga Kebir group. With its minimal reed cover and record-high evaporation rate, the lake is saline. It is from this lake-bottom that in 2010 Kröpelin, Melles and Karls extracted the core sample, dating from the present back to 10,940 years ago, that is still under study. |

n 2010, Kröpelin teamed up with the Quaternary and Paleoclimatology Group at the University of Köln, directed by Martin Melles, whose work in lake sedimentation analysis had nearly always taken him to polar regions.

n 2010, Kröpelin teamed up with the Quaternary and Paleoclimatology Group at the University of Köln, directed by Martin Melles, whose work in lake sedimentation analysis had nearly always taken him to polar regions.

“You have virtually no opportunity in hot desert areas,” says Melles. “The Sahara is as extreme and remote as Antarctica.”

Jens Karls, a doctoral student in paleoclimatology working under Melles, undertook much of the operation of the corer, which they set out in Lake Yoan. “You have a 30-kilogram [66-lb] weight and a system with ropes. Then you have to pull it up and let it drop again, and again. The upper sediments are very easy to penetrate, but when you reach sediments that are a little bit compact, then you have a coring speed of less than one millimeter per hit,” he says.

One millimeter is less than a year’s sediment. The team went down 16 meters (52½') in pursuit of layers from the dawn of the Holocene Era. Through stroke after stroke of the corer’s weight, in heat that, in sunshine on open water, often approached 50 degrees Centigrade (122° F), the team pressed on. In the end, they reached their goal: a continuous, 10,940-year “continental record of climate and environmental change.”

To understand “how our climate system worked in the past and will operate in the future,” says Melles, “you need these geological archives widely distributed over the globe.” Having one “representative core for the east Sahara is already a huge step.”

While analysis of the “long core” is still under way, says Kröpelin, “we have indications of really global climate events,” including, he says, “the relatively late introduction of the date palms, [and] we can explain or at least better understand the history of Pharaonic Egypt.” It is, he asserts, “the highest-resolution look we’ve ever had at climate history on the African continent.”

Baba agrees. “With Stefan Kröpelin, we’re in debt, having published in important international scientific journals. We are able to understand precisely how these lakes function,” he says. “Naturally, if we had the means, we’d do [the coring and analysis] here, and it would be uniquely a Chadian discovery.”

|

| George Steinmetz |

| Fingers of wind-driven sand continue to both shape and encroach upon the Lakes of Ounianga, and in this aerial view looking southwest over Lake Yoan, the sculpting power of the prevailing northeast harmattan wind is dramatically apparent. |

e’ve been traveling back and forth for an hour on a track in Eguibechi, some distance from Lake Yoan in Ounianga Kebir. Kröpelin is looking for an outcropping of diatomaceous earth that he spied on the way into town. He had noted its gps position, but he is having no luck. We retrace the route one last time. It is not what Kröpelin has been searching for, but I spot a swath of white over a rise.

e’ve been traveling back and forth for an hour on a track in Eguibechi, some distance from Lake Yoan in Ounianga Kebir. Kröpelin is looking for an outcropping of diatomaceous earth that he spied on the way into town. He had noted its gps position, but he is having no luck. We retrace the route one last time. It is not what Kröpelin has been searching for, but I spot a swath of white over a rise.

When we get to it, Kröpelin is ecstatic, and he immediately starts to work. Baba crouches over him. “You are witnessing really a new discovery,” Kröpelin says. “It’s a site I wanted to go to for many years. We urgently need it for the interpretation of the core we took down there in the lake so we can make a valid interpretation of the depth of the lake at the time of deposition.”

What we see, Kröpelin explains, is the shoreline of the original paleolake. ”There is still this rhizome, the ancient roots of reeds, and some places even trees which were growing when the lake was still shallow.” He estimates that here, they will prove to be about 8000 years old.

“On this side you find the highest exposed sediments from the ancient lake floor,” which he claims is evidence that the ancient lake was “50 or 100 times—an order of magnitude—more extensive than the present-day lake.” In other words, during the Green Sahara era, “as far as your eyes see, it was covered by water.”

Kröpelin packs the sediment into plastic bags labeled W76, the new discovery.

The wind whips up, and it starts drowning out Kröpelin’s voice. In the distance you can just make out the remnant sliver of oasis, its green palms and its sky-blue lake.

Baba comes over, puts his arm around me and spins me around to face the sand. “At Ounianga, you see the beauty of the desert,” he says. “But scientific research doesn’t stop, and we will uncover more secrets hidden in these lakes.”

|

Thanks to Chadian hosts with a sense of humor, award-winning Canadian writer and photographer Sheldon Chad (shelchad@gmail.com) was, for the duration of this expedition, affectionately nicknamed “Wardougou” Chad, which means “Man-who-loves-his-country” Chad. It fit fine from the start, he says, noting that “the unforgettable beauty of the Saharan landscape may be exceeded only by the elegance and generosity of the people who live there.” He currently lives in Brussels. |