|

| Above: Kruszyniany’s wooden mosque, built in the early 18th century and recently restored, is the oldest in Poland. Inset: Dżenneta Bogdanowicz. Inset below: Dżenneta Bogdanowicz. |

Vigorous and cheerful, Dżenneta Bogdanowicz gestures for visitors to come inside the small restaurant she runs out of her home in Kruszyniany, a village so remote it feels like it sits at the edge of the world. Bogdanowicz turns ‘round and ‘round the room. She can be seen and heard everywhere. She joins the guests at their tables, talks to them and smiles widely. Without hesitation, she gives away the recipes of her dishes, such as pierekaczewnik (meat dumplings) and syte (water with honey and lemon juice). She is just as open telling the story of her family, which comes from the land of today’s Belarus, and she shares details about its customs, traditions and religion, all of which have been pushed to the brink of extinction many times.

|

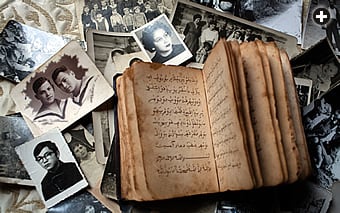

| Bogdanowicz family photographs and an antique Qur’an are among the personal artifacts that help rekindle interest in heritage and cultural expressions. Previous spread: Kruszyniany’s wooden mosque, built in the early 18th century and recently restored, is the oldest in Poland. Inset: Dżenneta Bogdanowicz. |

A tourism professional herself, Bogdanowicz first visited Kruszyniany (kru-shen-ee-ahn-ee), a couple kilometers (a mile) from Poland’s border with Belarus, more than 30 years ago on a tour that included small, sparsely populated villages, old farmyards, sandy roads and a powerful silence that, unexpectedly, tapped in her a compelling curiosity about her ancestors. Kruszyniany was no different from hundreds of other quiet villages in northeastern Poland, except for one thing: the celadon mosque that stands in the middle of it. To anyone unfamiliar with Kruszyniany, the mosque might simply be an unassuming place of worship. But to Bogdanowicz, Poland’s oldest Muslim house of prayer was a beacon illuminating a nearly forgotten heritage.

Polish Tatars are Muslim peoples of largely Central Asian descents and Polish customs, and in Kruszyniany, population 160, they live among both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christians. Heirs of the Mongol empire, Tatars are descendants of Batu Khan and the Golden Horde. While most live in Russia, others are descended from those who began gradual migrations west into what are now Belarus, Poland and Lithuania as early as the fifth century.

|

| In the dining room of her Tatarska Jurta, Bogdanowicz helps visiting teenagers learn to knead dough for one of her many Tatar recipes. |

Today, they are the survivors of centuries of wars and, most recently, communist political repression of religion, traditions and language. Yet, they fought to hang on to their historic identities—a fact underscored by the weathered, 18th-century wooden mosque wearing multiple shades of green, the centerpiece of Kruszyniany and the village’s only landmark of more than local note.

On her first tour through the village, Bogdanowicz also came across the Tatar mizar (cemetery), almost overgrown by forest. The moss-covered headstones, she realized, were those of her ancestors. “I had a moment of enlightenment. Suddenly I felt the call of the blood, of the land,” she recalls. For the first time, “I thought of myself as a Tatar of Polish origin. I had to come back.”

Tatars who settled in this region in the 14th century were speaking Polish, Lithuanian or Ruthenian by the 16th century, and their surnames had usually taken on Polish forms. Most of the dress and rituals customary of steppe nomads faded as well. But as the Kruszyniany mosque silently proclaims, their religion endured.

|

| It was when she found Kruszyniany’s Tatar mizar (cemetery), Bogdanowicz says, that for the first time, “I thought of myself as a Tatar of Polish origin. I had to come back.” |

Dżemil Gembicki, guide and conservator of the Kruszyniany mosque, says Polish Tatars have three defining characteristics: Tatar ethnicity, Polish nationality and Islamic religion. Zofia Bohdanowicz, from Bohoniki, a nearby village similar to Kruszyniany, in which stands the other of Poland’s oldest mosques, echoes his sentiments. “My family has been living here for generations, and I am Polish, but what distinguishes me and my children is the different religion. That is why we are Polish Muslims. If there is no Islam, there is no us,” she says. “I am a Polish Tatar Muslim. All these three terms are important for us.”

Bogdanowicz was only 20 when she made her first visit to Kruszyniany. After her visit, she returned to Bialystok for her studies. There, she met Mirek, her future husband and a native of the historic village. After marrying, they visited Kruszyniany often to see his family, which, similar to many other Tatar families, had been given its land in the late 17th century by Polish King John iii Sobieski in recognition of their ancestors’ military service. In her own tour-guide work, Bogdanowicz began to include Kruszyniany, where she took tourists to a cottage once inhabited by her husband’s family, as well as to the mosque and mizar.

It didn’t take long for her to realize that those drawn to this village had no place to eat and relax. Not minding tourists at their home, the couple set up a few tables and benches outdoors. The Tatarska Jurta (Tatar Yurt), as the simple restaurant was called, offered specialties of Tatar cuisine from late spring into the fall. Over time, and with the help of their three daughters, the couple renovated the house, and they began inviting guests inside to eat and sample a taste of Tatar family life. They eventually added on to the house, moved upstairs, and made the entire downstairs the restaurant, as word of the Tatarska Jurta was spreading. In 2003, she and Mirek moved there permanently.

|

| Bogdanowicz decorated her restaurant with family photos and Tatar traditional dresses. |

Now, arriving guests enter through a small room in which family photographs hang on the walls. Women in these pictures have Asian eyes and raven-black hair, and swarthy men wear Polish military uniforms.

“My mom rules in the kitchen. The dishes we serve are exactly the same as the ones I was eating in my childhood during Muslim holidays,” said Dżemila, one of Dżenneta and Mirek’s daughters. “My mom gathered some of the recipes when she was visiting Tatar households that are scattered all over Poland. Today, their pile would make a bulky cookbook.” Word of mouth and online reviews about the restaurant’s atmosphere, the vivacious personalities of the restaurant’s staff—especially Bogdanowicz—and the refined Tatar cuisine continue to spread. Now, connoisseurs are traveling for hours to eat pierekaczewnik and drink coffee laced with cardamom.

|

| Guide and conservator of Kruszyniany’s mosque, Dżemil Gembicki sits with a copy of the Qur’an in front of the mosque’s wooden mihrab, oriented toward Makkah. Polish Tatars, he says, have three defining characteristics: Tatar ethnicity, Polish nationality and Islamic religion. |

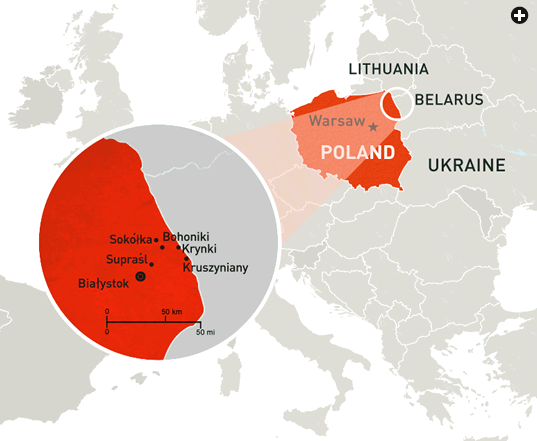

Patrons who talk to Bogdanowicz between scrumptious bites inevitably learn that Kruszyniany is a part of the historic Tatar Trail, largely a network of roads that connect seven main towns and villages in northeast Poland, all sparsely populated and influenced in different ways by Polish and eastern European customs. About 150 kilometers (90 mi) at its greatest length, the trail winds through the picturesque Sokółka Hills and Knyszyńska Forest to connect Sokółka, Bohoniki, Malawicze, Krynki, Kruszyniany, Supraśl and its most populous town, Białystok. Following the trail, one can not only learn about the history of Polish Tatars, but also get a taste of modern life and culture. One of the most noteworthy places on it is Kruszyniany, as it is one of few villages that, due almost entirely to Bogdanowicz’s efforts, comes back to life during Muslim holidays and cultural festivals.

|

| Like Bogdanowicz and other Tatar families, Bronislaw Talkowski lives on the land given to his family in the late 17th century by King John iii Sobieski as compensation to Tatar soldiers for their military service. Talkowski is chairman of Kruszyniany’s Muslim parish, one of only two in Poland that predate World War ii. |

Bogdanowicz noticed the need for cyclic events that would allow for the rebirth of Tatar traditions and customs. It was on her initiative that the first Festival of Polish Tatars’ Culture and Tradition was organized a few years ago. There were band performances, dances, songs, handicraft demonstrations and competitions. Everyone was invited to participate in Tatar cooking workshops, bow shooting and horse riding. Interest exceeded even her boldest expectations. “Again, Kruszyniany became teeming and lively. I am happy that many Polish Tatars, just like me 30 years ago, felt the call of the blood and now want to come back,” she says.

Seven years ago, she reintroduced the Sabantuy, which literally means “Plough Festival,” a Tatar Muslim folk tradition dating back more than 1000 years that celebrates the end of the spring agricultural season. Villagers and their guests gathered for games, competitions, Mongolian-style archery and horseback riding, and the most valuable prizes were rams and handmade towels.

Today, visitors who choose to tour the mosque in Kruszyniany may be greeted by a beaming Gembicki, whose Central Asian features reveal his unmistakably Tatar ancestry. He explains how the mosque is divided into spaces for men and women, and he shows the wood-covered walls decorated with calligraphy and pictures of Makkah and Madinah. The floor is covered with carpets. The mihrab in the southern wall indicates the direction of Makkah. Above it, a brightly lit crescent with a star shines. “It is the symbol of Islam,” Gembicki says, as he sits on the stairs of the minbar (pulpit), where the imam, or prayer leader, preaches during the weekly Friday service. He explains that although many Polish Muslims no longer understand Arabic, the Qur’an is nevertheless recited in Arabic.

|

| Above: A signpost in Krusziniany points the way to the rest of the world. |

|

Then, Gembicki leads visitors to a small hill covered with trees. Their thick canopies guard the Muslim cemetery where Bogdanowicz found her ancestors’ graves. Here, it is clear how Tatars blended with their eastern European surroundings. Through years of wear and tear, Arabic, Russian and Polish inscriptions can be seen on the headstones dating from the 18th century.

The history of Tatar settlement in northeastern Poland is connected with the King John iii Sobieski, whose life was saved by Colonel Samuel Murza Krzeczkowski, commander of the Tatar regiment, during the battle of Párkány, which occurred as part of the Battle of Vienna in 1683 against the Ottoman Turks. As wages for their service, the king gave the Tatars the lands along what is today’s Tatar Trail. Even today, residents of Kruszyniany can point to the place, overgrown with old linden trees, where the manor house of Krzeczkowski once stood.

The Tatars slowly blended into their newly bestowed homeland. “They gave in to it consciously, but at the same time, they were protecting their beliefs. In Poland, being Tatar also meant being Muslim,” says Ali Miśkiewicz, a historian and editor of Yearbook of Polish Tatars and other works on Tatar history. Their traditions survived in major centers both in Lithuania and in Poland, where they taught their religion and built their own places of worship, he adds. And as Musa Czachorowski, spokesperson for the mufti (chief Islamic legal official) of the Republic of Poland, says, “Muslims lived in Poland for 600 years and the Polish law never forced us to act against the rules of Islam.”

|

In the 1920’s, about 6,000 Polish-Lithuanian Tatars lived among some 19 communities and worshipped in 17 mosques. In 1925, they established the Muslim Religious Association (Muzułmański Związek Religijny) and attempted to unite all Muslims in Poland. They also established the Cultural and Educational Union of Polish Tatars, where they developed social and cultural activities.

Living in a non-Muslim country, Polish Tatars naturally absorbed their surroundings and, to a certain degree, assimilated. For instance, it is typical that Polish-Lithuanian Tatar women have never covered their heads or faces. “Although I sit with women in the mosque, there are equal rights at home,” Bogdanowicz says.

Architecture was influenced as well. The wooden mosques in Kruszyniany and nearby Bohoniki differ in outward appearance only a little from Catholic and Orthodox churches, except for their distinguishing crescents.

|

| Dżemil and Kasia Gembicki, who are, respectively, Muslim and Catholic, play at home in Kruszyniany with their children. The couple explains they are raising Selim, left, Muslim, and Lilia Catholic. |

Tatar writing is another example of cultures intermingling. Their literature was written in Polish and Lithuanian, but also contained Arabic, Ottoman Turkish and Tatar elements. For the Qur’an and other religious writings, Tatars at times used a form of Arabic developed to allow phonetic reading of the words in either Polish or Belarusian.

Some things, however, remained the same. Weddings continue to be held on large swaths of sheepskin, a symbol dating back to the Golden Horde that represented home, wealthand stabilization.

However, in what seemed like an overnight sweep, Soviet communists worked feverishly after World War ii to stamp out the individual cultures and religion of Tatars throughout Poland, Russia, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine and Belarus. Settlements, educational and cultural institutions, and many mosques were destroyed. Members of the Tatar intelligentsia were arrested, some repeatedly, deported or murdered. The population of 6000 Polish-Lithuanian Tatars was reduced to around 3000.

At that time, the communist authorities did not accept any national and ethnic minorities. Thus the “Tatar Trail,” established in the 1960’s, was promoted as a mere tourist attraction, a ploy to reduce the Polish Tatars to an ethnographic curiosity. Polish Muslims were forced to fraternize with immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa on the basis of “religious community.” This contributed to the reduction of ethnicity and, in many cases, the complete loss of it. Many Tatars who were born at that time do not know today how to pray in Arabic.

|

| In Białystok, the largest town in the region, the Tatar folk group Bunczuk helps both adults and children maintain the traditional folk repertoire of songs and dances. |

Not wanting to be identified by name, a Tatar woman in Sokółka says, “I have not learned religion as it should be done. I do not know and cannot do many things. Every now and then, a Tatar would come to our house to teach us how to pray, and my grandparents taught me to read Arabic letters.”

After the fall of communism in 1989, the Tatar community began to revive itself in Poland. The Muslim Religious Association of Poland now has eight communities—Białystok, Gdańsk, Warsaw, Bohoniki, Kruszyniany, Poznań, Bydgoszcz, and Gorzów Wielkopolski—that embrace the population of about 5000 Polish Tatar Muslims. The association represents Polish Muslims before the state, provides religious and spiritual services, and maintains historic sites and cemeteries, such as the one in Kruszyniany. It also hosts marriages, funerals and prayer services. The association organizes the celebrations of Muslim holidays—Kurban Bayram (‘Id al-Adha) and Ramadan Bayram (‘Id al-Fitr)—and other ceremonial occasions.

Today, many of the Muslim community’s rituals are performed not only for Muslims, but also for non-Muslims interested in inter-religious dialogue. “It is conducive to learning about each other, building respect, discovering common values in both religions and breaking stereotypes,” says Agata Skowron-Nalborczyk, an associate professor at the Faculty of Oriental Studies at the University of Warsaw.

Today, about 20,000 to 30,000 Muslims live in Poland, and they comprise a mere 0.6 percent of Poland’s population. Although the community is small, it is diverse: The largest group of Muslim newcomers hails from Arab countries, but also there are Turks, Bosnians and refugees from Somalia, Afghanistan, Chechnya and Syria.

Of the 5000 Tatars in Poland, most live in Białystok and other cities. Tatar villages such as Kruszyniany and Bohoniki are mostly deserted except during Muslim holidays when Muslims travel there with their families to pray in mosques and visit cemeteries. It is then they taste the increasingly famous dishes offered by Bogdanowicz.

|

| In a Białystok classroom, Maria Aleksandrowicz-Bukin, who chairs the Muslim Religious Association in that town, leads a lesson about Islam. |

Polish Tatars are keenly aware that the survival of culture depends on children. For several years schools in Tatar communities have begun to offer curriculum for Tatar children, and community-based cultural and religious instruction is increasingly common. They also get to know Tatar tradition and history from the stories and values handed down by the family, especially grandparents, and from activities of Tatar organizations and associations.

For many years, Tatars often dreamed and prayed that they once again could teach the forgotten Tatar language. They realized their dream in 2012, when the opening lesson of Tatar language was held in Białystok. “After over 400 years of ‘silence,’ we have the opportunity to use the language of our ancestors,” announced the Central Council of the Union of Tatars of the Republic of Poland.

Because of their heritage, Tatars may well be Poland’s strongest bridge between the West and the East, between Islam and Christianity, as they retain their religious roots while comfortably living among people of other heritages and faiths. “Tatars,” as Miśkiewicz says, “who feel Polish, should never forget about their origin and belief, but as Tatars they should always remember that Poland has been their homeland for 600 years, and that they will always be an integral part of the society.”

|

Katarzyna Jarecka-Stępień (jareckakat@gmail.com) holds a doctorate in humanities from Jagiellonian University in Krakow, where her research focuses on how society and culture influence the effectiveness of international aid. She also runs workshops in intercultural communications. |

|

Photojournalist Aga Luczakowska (www.agaluczakowska.com) began her career with the Dziennik Zachodni (Western Daily) newspaper in Poland, and she currently freelances from Bucharest, Romania. Her work has appeared in the New York Times’ “Lens” blog, The Washington Post and The Guardian. |