|

|

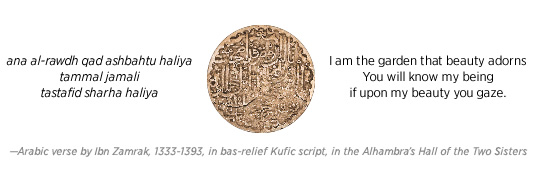

| above: metropolitan museum of art / art resource; below: josé miguel puerta vílchez |

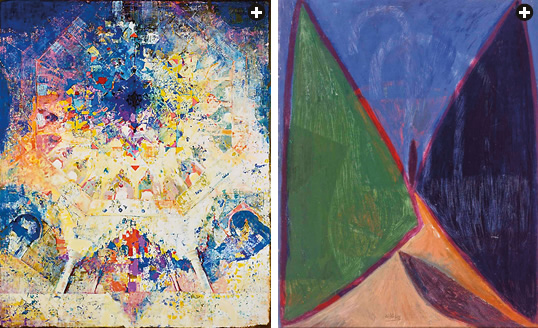

| In the early 1860’s, Hudson River School painter Samuel Colman was among the first American artists to visit Spain. “The Hill of the Alhambra,” 1865, reflects the popular ideal that pictorial beauty and grandeur stimulate the senses to higher awareness. |

|

FROM EVERY DIRECTION approaching Granada, in the Spanish region of Andalucía, the southernmost in Europe, you see it: the walled fortress, palace and garden of the Alhambra, anchored to its promontory that dominates the city. With its back to the high Sierra Nevada, it scatters at its feet a downtown urban scene of modern buildings interspersed with the remains of history longer than a thousand years. To the north, the Cubist landscape of the Albayzin, or Moorish quarter, climbs an opposite hill and faces the downtown from its sinuous labyrinth of streets that still seem to echo with ancient voices.

The Alhambra has long been upheld as the most precious gem of Hispano-Islamic art. It has profoundly inspired countless artists, from Granada and around the world, who regard it almost universally as an epitome of esthetics, replete with historical, mathematical, spiritual, mystical, sensual and oneiric aspects. Each artist has interpreted it and, in turn, let it exert its own influences, according to the artist’s own style, whether historic, scientific, romantic, avant-garde or contemporary.

|

|

| top and above right (owen jones): bridgeman images; above left (gÓmez-moreno): album / art resource |

| Historicist painters of the 19th century used the Alhambra as a symbol and a setting for events they rendered in epic visual style laden with Romantic nostalgia. Top: “The Fall of Granada in 1492” by Carlos Luis Ribera y Fieve, 1890, and (above, left) “Boabdil’s family leaving the Alhambra” by Manuel Gómez-Moreno González, 1883, both imagine the Catholic conquest and the resulting exile of the Nasrid sultan and his family. Above right: Recording many of the Alhambra’s designs with both a scientific and a Romantic eye, Welsh architect Owen Jones in 1856 declared it “the very summit of perfection of Moorish art.” |

he palace of the Alhambra was built between the 13th and 15th centuries by the Nasrid sultans, the last of eight centuries of Muslim rulers in al-Andalus, the name given to Muslim Spain from which comes today’s Andalucía. By the 1400’s, the court at the Alhambra was living off brilliant reflections of past glory, uncertain of its future. Nasrid political survival depended on military aid from the North African Marinid dynasty as well as protection from the Christian kingdom of Castile in exchange for tributes. These external pressures, as well as internal power struggles, weakened the Nasrids, and their expulsion in 1492 brought on the final collapse of Muslim Spain.

he palace of the Alhambra was built between the 13th and 15th centuries by the Nasrid sultans, the last of eight centuries of Muslim rulers in al-Andalus, the name given to Muslim Spain from which comes today’s Andalucía. By the 1400’s, the court at the Alhambra was living off brilliant reflections of past glory, uncertain of its future. Nasrid political survival depended on military aid from the North African Marinid dynasty as well as protection from the Christian kingdom of Castile in exchange for tributes. These external pressures, as well as internal power struggles, weakened the Nasrids, and their expulsion in 1492 brought on the final collapse of Muslim Spain.

Built under these precarious conditions, the monument’s resistance to the passing of time is all the more amazing, because the materials available to the Nasrids were only simple, even poor ones: plaster, stucco, wood and ordinary, easily worked stone.

Yet what they lacked in monumental materials, they made up for in prodigious knowledge. Their unnamed architects had a highly sophisticated grasp of classical Greek and Islamic mathematics, from both practical and mystical, spiritual perspectives that regarded numbers as the highest, most profound of human concepts. Following these standards, they proportioned and decorated the Alhambra to reflect relationships among numbers, the cosmos and people. For example, the classical Greek concept of the “golden proportion” or golden section is used throughout the palace—in the endless geometry, in the exuberance of its designed gardens, in the ornamentation of its fabulous stuccos and in the countless panels of elegant Kufic calligraphy.

|

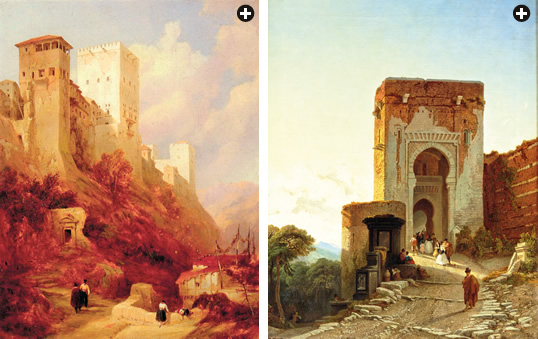

| left: wikimedia commons; right: bridgeman images |

| In 1832, the year Washington Irving’s Tales from the Alhambra was published, English artist David Roberts visited Spain, but he painted “Tower of Comares,” left, in 1838, shortly before he set off on what was to become his most famous journey, to Egypt and the Levant. Right: Like Roberts, French artist Francois Antoine Bossuet, painting the Alhambra’s “Porte de Justice” in the 1870’s, used what were by then well-developed techniques of Romantic Orientalism: exquisitely warm lighting, precise detail (influenced by the invention of photography) and small figures that accentuate exaggerated space and perspectives—techniques evident also in the images below. |

In 1492, the Christian monarchs of Castile took the keys to the Alhambra while their nobles and merchants took the most prominent Moorish and Jewish buildings in the city. In the early 16th century, some of the Alhambra’s palaces were partly demolished—we don’t know how many as no records were kept—to make way for the Renaissance palace that Emperor Charles i of Spain (Charles v of Germany) intended to use to make Granada his capital.

While the Renaissance palace was built and still stands today, Granada never became Charles’s capital. Some two centuries passed, during which the Alhambra fell into disuse, a long dream of oblivion in which the splendor of the past was covered by dust, surrendered to time. Its magnificent rooms and gardens became dwellings for squatters and vagabonds. As it turned out, this became an ideally appealing scene to artists of the newly emergent Romanticism.

Beginning in the early 19th century, Granada undertook a dramatic urban modernization plan that, over the next 100 years, resulted in the demolition of much of its Islamic architectural patrimony. In 1828, a writer from New York named Washington Irving visited Granada during a short tour of Spain. (A dozen years later, he came back to Spain to represent his country as ambassador.)

|

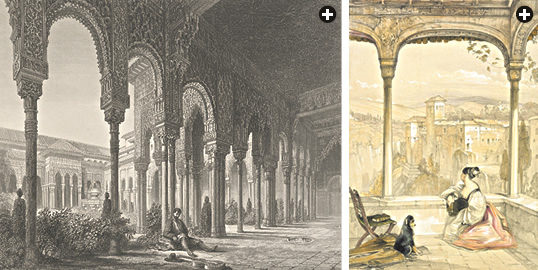

| (2): bridgeman images |

| Also in 1832, French draftsman Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey was in his late 20’s when he visited the Alhambra. “Court of the Lions,” left, an engraving from that visit, magnifies both the height and the area of the courtyard for dramatic effect; the drowsy guitarist can be viewed as a metaphor for the common Orientalist idea of a “somnolent East.” That same year, English watercolorist John Frederick Lewis began two years’ residence in Spain, during which he produced the untitled image, right, of a woman gazing at the Alhambra’s towers. Both artists’ works were widely published to popular acclaim. |

The history of Granada, and the Alhambra in particular, fascinated Irving, who even set up residence in the dilapidated palace, and he started to work to convince both politicians and society of the importance of preserving it as well as other historic parts of the city. In the same way, Irving found in the Alhambra inspiration for what became his best-selling classic Tales of the Alhambra, published in London in 1832. Many of the dozens of later editions were illustrated by notable artists including Gustave Doré, Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey and others who also illustrated other literary Romantic works and travel literature.

Though Irving can be credited with popularizing the Alhambra, he was himself a follower of a trend that had started a century earlier, as the compass needle of European art began to point toward the continent’s most southern area—Andalucía—as well as North Africa. Fueled by the heat of Romanticism, and nurtured by the popularity of Oriental esthetics stemming from books such as the early 18th-century editions of One Thousand and One Nights and, near the end of that century, the encyclopedic Description de l’égypte, Romantic artists flocked south. They found both thematic and iconographic keys in the history and civilization of al-Andalus in general, in Granada more specifically and in the Alhambra most particularly of all. Granada and its Alhambra became so renowned they grew into artistic objects of desire, secular pilgrimage destinations. They were popularized further by the Romantic Travelers, comprised mainly of English and Scottish (and some French and German) writers, painters and poets, who extolled the Alhambra as a threshold of the Orient or, as they named it, “an Orient at home.” They were encouraged, or perhaps enabled, by a new genre of travel books, notably Richard Ford’s 1845 Guide for Travellers in Andalusia and Readers at Home. Granada’s echoes of a “lost kingdom,” even a “lost paradise,” its atmosphere of ruins and the visibly mixed cultural and ethnic characteristics of its people, all made an ideal tableau for the Romantic artist. It was an inexhaustible source from which artists have never stopped drinking.

Though Irving can be credited with popularizing the Alhambra, he was himself a follower of a trend that had started a century earlier, as the compass needle of European art began to point toward the continent’s most southern area—Andalucía—as well as North Africa. Fueled by the heat of Romanticism, and nurtured by the popularity of Oriental esthetics stemming from books such as the early 18th-century editions of One Thousand and One Nights and, near the end of that century, the encyclopedic Description de l’égypte, Romantic artists flocked south. They found both thematic and iconographic keys in the history and civilization of al-Andalus in general, in Granada more specifically and in the Alhambra most particularly of all. Granada and its Alhambra became so renowned they grew into artistic objects of desire, secular pilgrimage destinations. They were popularized further by the Romantic Travelers, comprised mainly of English and Scottish (and some French and German) writers, painters and poets, who extolled the Alhambra as a threshold of the Orient or, as they named it, “an Orient at home.” They were encouraged, or perhaps enabled, by a new genre of travel books, notably Richard Ford’s 1845 Guide for Travellers in Andalusia and Readers at Home. Granada’s echoes of a “lost kingdom,” even a “lost paradise,” its atmosphere of ruins and the visibly mixed cultural and ethnic characteristics of its people, all made an ideal tableau for the Romantic artist. It was an inexhaustible source from which artists have never stopped drinking.

|

| images courtesy of the artists except: 1) museo sorolla, madrid; 2), 3) bridgeman images; 7) courtesy juan manuel segura & francisco jiménez collection, granada; 8) album / art resource; 10) © artists rights society (ars), new york / vegap, madrid; 13) archivo oronoz |

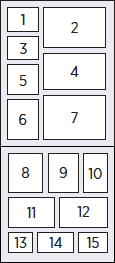

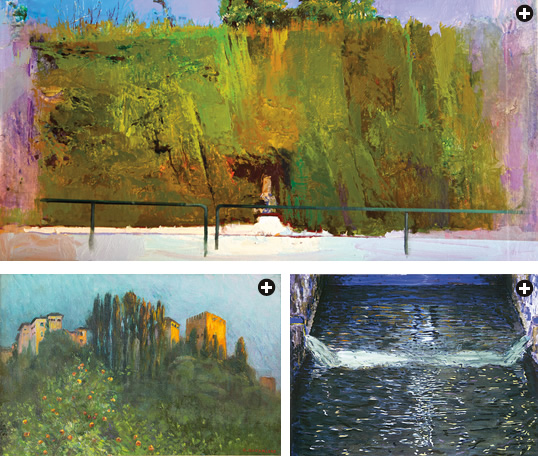

For artists, the most popular subject at the Alhambra may be its rectangular Court of the Myrtles, or Patio de los Arrayanes, which is also known as the Court of Comares, adjoining as it does the Comares Hall, or Hall of the Throne, that appears in the background of most of these paintings. In this courtyard, and in the Hall of Comares, sultans held audiences and hosted delegations amid the symmetry conferred on the space both by the perfectly articulated columns and arches that make the transition from the courtyard to the hall, and by their reflections on the surface of the pool that occupies most of the courtyard’s space. The pool thus reflects the sky even more than it reflects the architecture, and its elemental, tranquil simplicity contrasts with the rich ornamentation of the columns and vaults as well as the social and political complexity of the activities it has witnessed. For artists, this is a place where reflections make and remake the scene in endlessly singular visions, a few of which are shown here, spanning 178 years. For artists, the most popular subject at the Alhambra may be its rectangular Court of the Myrtles, or Patio de los Arrayanes, which is also known as the Court of Comares, adjoining as it does the Comares Hall, or Hall of the Throne, that appears in the background of most of these paintings. In this courtyard, and in the Hall of Comares, sultans held audiences and hosted delegations amid the symmetry conferred on the space both by the perfectly articulated columns and arches that make the transition from the courtyard to the hall, and by their reflections on the surface of the pool that occupies most of the courtyard’s space. The pool thus reflects the sky even more than it reflects the architecture, and its elemental, tranquil simplicity contrasts with the rich ornamentation of the columns and vaults as well as the social and political complexity of the activities it has witnessed. For artists, this is a place where reflections make and remake the scene in endlessly singular visions, a few of which are shown here, spanning 178 years.

From top left: 1. Joaquín Sorolla of Valencia, Spain, 1917; 2. lithograph by Girault de Prangey, 1836-37; 3. American Impressionist Frederick Child Hassam, 1883; 4. American Orientalist Edwin Lord Weeks, 1876. Paintings 5-15 are by artists from Granada: 5. Juan Vida, 1996; 6. Leonor Solans, 2005; 7. Eugenio Gómez-Mir, 1920; 8. José Maria López-Mezquita, early 20th c.; 9. Jesús Conde, 2009; 10. José Guerrero, 1974; 11. Socram, 2009; 12. Silvia Abarca, 2014; 13. José Maria Rodriguez-Acosta, 1904, and his nephew, 14. Miguel Rodriguez-Acosta, 2007; 15. Brazam, 1993, who says, like many, that he is indelibly influenced by the Alhambra, by “the transparency of its light, the sound of water.” |

|

The Romantic artists, explains art historian Ignacio Henares Cuéllar of the University of Granada, “also found the Alhambra met criteria of their new theories of the Sublime, a philosophy that maintains that the visible world is a reflection of the spiritual one. This crystallizes for the Romantic Travelers in Andalusia, and the Alhambra in particular comes to define the esthetic fundamentals of Mediterranean Orientalism, a rich romantic imagination which advances the first big chapter of modernity.”

Maria del Mar Villafranca, general director of the Council of the Alhambra and Generalife, explains that especially during the second half of the 19th century, the Alhambra was a destination of choice for “cultured travelers, most of them keeping in the line of the Romantic artists such as David Roberts, John Frederick Lewis or Gustave Doré.” In addition, “personalities such as [Henri] Regnault lived with Mariano Fortuny, perhaps the most emblematic and exemplary traveler, since he also was both an art collector and art reformist.” This extended to artists of further diverse nationalities, notably the American Edwin Lord Weeks and the German Adolf Seel.

Under the umbrella of Romanticism emerged the artistic current that became known as Orientalism. Often carrying with it a varying mix of colonialist ideas and attitudes, Orientalism burst into the painting scene throughout the Mediterranean region wherever European artists found inspiration in largely Muslim, Arab and North African subjects.

According to Jesús Conde, a painter and a professor of fine arts at the University of Granada, much of the Orientalist impulse stemmed from Europeans’ search for their identity in an increasingly heterogeneous world. “That need of defining the Orient creates a whole movement,” he says. “We need to define ourselves in order to be identified as Europeans, and this could only be possible by looking at the mirror of ‘the Other.’” Yet, he adds, it was more than this: “Disillusionment further fueled a ‘flight from the West,’ where the rise of industrialism and pragmatism created a boring and suffocating atmosphere, toward not only the culture of the Others, but also toward the countries that keep, between their sky and earth, the ruins and treasures of ancient civilizations … everybody wanted to travel, to unravel and bring to surface their own desires in those exotic lands.”

|

| Left: © 2014 succession h. matisse / artists rights society (ars); Right: ©2014 m.c. escher co., all rights reserved, www.mcescher.com |

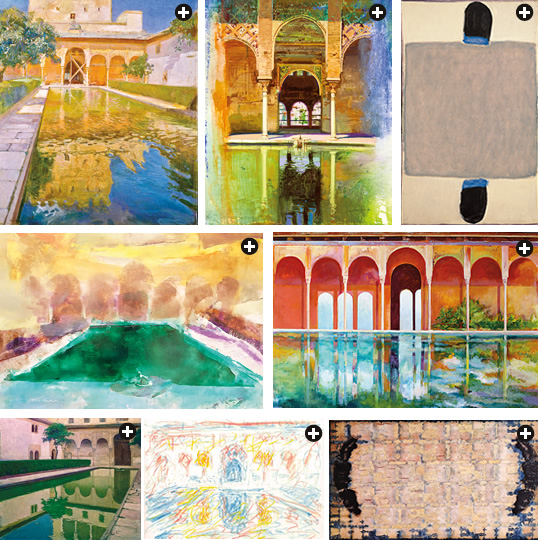

| French painter Henri Matisse, who visited for three days in 1910, was “the last Romantic artist, and the first Modern one,” says Maria del Mar Villafranca. “The influence of the Alhambra on Matisse did not result in mimesis but rather in something more profound”: motifs that subsequently infused his style, as seen in the patterns in his 1911 “Interior with Aubergines,” left. Similarly, a visit in 1922 inspired Dutch artist and mathematician M.C. Escher to depict neither the palace nor its art, but rather to draw from the Alhambra’s art a personal inspiration for his own interlocking, infinitely repeatable patterns that often resemble the traditionally Islamic geometric and vegetal patterns he saw in the Alhambra, as in his 1941 woodcut “Fish,” right. |

In this way, the Romantic artists discovered at the Alhambra an essential scene, an iconographic device so prodigious it could speak in as many visual languages as the artists could paint.

At the same time Romantics were flocking south, the very industrialism they tried to shun was providing their art with new ways of distribution and consumption that expanded their artistic opportunities. Until then, much painting had been financed by aristocracies or the Catholic Church, normally destined for the walls of palaces and religious buildings. Now, new manufacturing techniques enabled mass production of lithographs and engravings, making prints and paintings much cheaper (and leading to many forgeries). Art became a marketplace commodity accessible to a new social class—the bourgeoisie—as both spectators and purchasers.

In addition, the need and the means to provide illustration for Romantic literary books popularized a visual dimension for literature previously available only in the most precious, hand-illuminated manuscripts. This further attracted artists to many subjects, and they enjoyed the challenge of graphically showing the lyric warmth of Romantic writing while at the same time appearing to reflect precisely realistic images— thanks in part to the emergence of photography.

David Roberts, famous for his lyrical realism in treating Middle Eastern subjects, was one of the seminal artists from whose esthetic choices the iconography of Romantic Andalucía derived. His most famous work of the region, “Tower of Comares” (see p. 6), shows a truly Romantic image in which the real melts into fantasy. Similarly, the engraver Gustave Doré skillfully handled the presence of people in his Alhambra scenes, using strange characters of clearly legendary traits, all the while mastering the power of light, color and the lightness of the Alhambra’s architecture, to which he gave such astonishing perspectives that despite his apparent realism, the viewer is immediately transported to the Romantic Orientalist’s oneiric world.

|

| left: museo sorolla, madrid; right: courtesy of the artist |

| The same year Matisse visited the Alhambra, Valencian painter Joaquín Sorolla, by then in his late 40’s, was starting to produce works in southern Spain, and at the Alhambra in particular, that bridged Impressionism, Symbolism and Modernism, including “Torre de los Siete Picos,” left. Contemporary painter Miguel Rodriguez-Acosta, who grew up in a home alongside the Alhambra’s walls, pays homage to the color red—the Arabic root of the name al-hamra—in his 2009 painting “Vesperal” (“Chant”), which balances colors, patterns, geometry and brushwork, right. |

John Frederick Lewis, whose popular lithographs, watercolors and oils were widely reproduced, emphasized Oriental and Mediterranean atmospheres by including architecture and arabesques as the main ingredients of a “lost civilization” esthetic, or a fantastic “al-Andalus paradise.” On the other hand, realist and Hispanist scholar Sir Richard Ford and his wife Harriet Ford produced many drawings with empirical details that, accompanied as they were by travel-oriented texts, became essential for readers who wished to understand the country realistically.

Also at this time, the figure of the “art dealer” appeared to act as a broker between artists and customers. Dealers opened private, commercial art galleries that put artworks —and consequently the subjects of art, in this case the Alhambra—in a new position as commodities and indeed investments. Granada gallery owner Ceferino Navarro explains that the Alhambra’s presence is so pervasive that “it is difficult for any artist resident in Granada—either born in the city or coming from outside—to live unrelated to the Alhambra’s influence, and not surrender to the temptation of immortalizing it.” Along the Gran Vía de Granada, one of the main downtown streets, the gallery owned by Miguel Ángel Hortal shows in its shop windows many depictions of the Alhambra, which attract the attention of passersby, and many art lovers come here to purchase works reflecting the latest esthetic trends with the Alhambra as a subject.

Also at this time, the figure of the “art dealer” appeared to act as a broker between artists and customers. Dealers opened private, commercial art galleries that put artworks —and consequently the subjects of art, in this case the Alhambra—in a new position as commodities and indeed investments. Granada gallery owner Ceferino Navarro explains that the Alhambra’s presence is so pervasive that “it is difficult for any artist resident in Granada—either born in the city or coming from outside—to live unrelated to the Alhambra’s influence, and not surrender to the temptation of immortalizing it.” Along the Gran Vía de Granada, one of the main downtown streets, the gallery owned by Miguel Ángel Hortal shows in its shop windows many depictions of the Alhambra, which attract the attention of passersby, and many art lovers come here to purchase works reflecting the latest esthetic trends with the Alhambra as a subject.

n 1922, the Dutch mathematician and artist M. C. Escher visited Granada and found in the Alhambra a mathematical and geometric universe. “Many of the coloured mosaics in the palaces of the Alhambra’s walls and floors show us that Moorish people were masters in the art of filling the plane by means of geometric figures without leaving gaps,” he wrote. But his inspiration did not lead him to depict the Alhambra so much as let it become a catalyst for the growth of his personal style. This is evident in many of his hypnotically interlocking, infinitely repeatable patterns in which he used abstractions of humans and animals in ways that resemble the traditionally Islamic geometric, vegetal and calligraphic patterns he saw exemplified in the Alhambra.

n 1922, the Dutch mathematician and artist M. C. Escher visited Granada and found in the Alhambra a mathematical and geometric universe. “Many of the coloured mosaics in the palaces of the Alhambra’s walls and floors show us that Moorish people were masters in the art of filling the plane by means of geometric figures without leaving gaps,” he wrote. But his inspiration did not lead him to depict the Alhambra so much as let it become a catalyst for the growth of his personal style. This is evident in many of his hypnotically interlocking, infinitely repeatable patterns in which he used abstractions of humans and animals in ways that resemble the traditionally Islamic geometric, vegetal and calligraphic patterns he saw exemplified in the Alhambra.

Escher’s response, says Villafranca, was a common one in the 20th century, when “artists’ travel experiences generate more experimental and innovative ideas,” carried out sometimes as pleine-air painting, and at other times as Symbolism, Impressionism or aspects of the avant-garde schools.

A dozen years before Escher’s visit, French artist Henri Matisse spent three winter days in Granada. The Alhambra had been opened recently as a public tourist attraction. This short time was enough for the artist to feel “a break with traditional representation, the key to the artistic vanguard,” says Villafranca, who organized an exhibition in 2010 titled “Matisse and the Alhambra.” Known as the master of color, he had long felt a fascination for Islamic art, especially after his travels in North Africa. But Granada proved decisive, catalytic; it was an epiphany of new forms, not just ornamentation, but also a game played by the light and shadows that filtered through the lattice walls.

|

| left: courtesy of the artist; right: museo nacional centro del arte reina sofia |

| Left: In the luminous expressionism of contemporary Granada painter Maria Teresa Martín-Vivaldi’s 1996 “Hall of the Two Sisters,” the vaults, windows and tiles of the Alhambra’s most famous dome refract and dissolve. Right: After exile following the Spanish Civil War, Manuel Ángeles Ortiz became particularly devoted to the Alhambra, where in 1959 he painted “Paseo de los cipreses” (“Path of the Cypresses”), where seemingly simple geometry produces an unexpectedly vertiginous perspective. |

“The Alhambra is a marvel,” he wrote to his wife. “I feel intense emotion there.” It is here he began to break down his mental boundary between decorative art and “pure” art, as at the Alhambra—as in much Islamic art—they inhabit a common space.

“The influence of the Alhambra on Matisse did not result mimesis but rather something much more profound,” says Villafranca. After that, inspirations from the motifs of the Alhambra seem ever-present in his work, either as backgrounds or as central motifs in objects and textile designs. He was, says Villafranca, “the last Romantic artist, and the first modern one.”

hen I need inspiration, I always go to the Alhambra to be there to soak in the golden dust of it light,” Granada abstract artist Manuel Rivera (1927-1994) used to say. He was among the founders of the El Paso collective that helped guide the avant-garde after the Spanish Civil War. For him and other artists of the early 20th century, the Alhambra endured as a beacon of inspiration.

hen I need inspiration, I always go to the Alhambra to be there to soak in the golden dust of it light,” Granada abstract artist Manuel Rivera (1927-1994) used to say. He was among the founders of the El Paso collective that helped guide the avant-garde after the Spanish Civil War. For him and other artists of the early 20th century, the Alhambra endured as a beacon of inspiration.

|

ABOVE, LEFT: colecciones museograficas del patronato de la alhambra y generalife;

Top and Above,Right (2): courtesy of the artists |

| The gardens of the Alhambra have been a recurring subject among modern and contemporary artists who believe “the artist should not imitate Nature; instead he must build a new reality from it,” says Granada artist Juan Vida. Above, left: “La Vista de la Alhambra” (“View of the Alhambra”) by Gustavo Bacarisas, 1909-10. Top: “Muro vegetal” (“Vegetal Wall”) by Jesús Conde, 2012. Above, right: “Alberca Azul” (“Blue Pool”) by José Manuel Darro, 2000. |

Similarly, and influenced much by Matisse, Granada vanguard painter Manuel Ángeles Ortiz (1895-1984) became renowned for his ability to “capture with abstract evocations the memory and the subtle hints of its forms,” according to contemporary artist José Manuel Darro, also from Granada. “The Nasrid geometry is an invitation and an intellectual challenge,” he adds. “Even though the Alhambra has been painted almost to saturation as a picturesque, exotic subject or as a landscape, it has been much less common to re-create the language and the geometry of its fragments.”

The underlying visual language and the geometry of the Nasrid palace also deeply inform the contemporary painting of Miguel Rodriguez-Acosta, born in Granada in 1927. His studio is in his family’s former home just a few minutes’ walk from the palace gardens. He explains the extent to which the Alhambra represents an icon of beauty to Granadans with a family anecdote: “During a trip to Versailles that my family made when I was a kid, while they were walking around the gardens of the French palace, my father asked our nanny if she had liked it. The lady, who was born in Granada and unable to express it otherwise, said, ‘It’s an Alhambra like all Alhambras!’”

Having grown up with the Alhambra as a premise of beauty, he is today one of the most internationally recognized of the city’s artists. His works speak through color, pattern and rhythm; they reference volumetric features and gardens to achieve “a fertile synergy” between his roots and his lifelong personal love of Italian traditions, writes Maria Dolores Jiménez-Blanco in the artist’s 2003 retrospective catalog. “Textures of infinite chromatic layers … which Rodriguez-Acosta creates with infinite delicacy, have a possible explanation in the daily contemplation of walls whose plaster has been chipped and broken by the passing of centuries.” She continues: “The network of brushstrokes that makes up the surface of his pictures, conferring on them the immediacy of the gestural and connecting them to the trends of 20th-century expressive abstraction, also have a correlation with the plaster filigree on the upper part of the Alhambra’s inner walls.”

|

| Left: courtesy of the artist; Right: colecciones museograficas del patronato de la alhambra y generalife |

| Granada artist Augusto Moreno works with metal sheets on which firings and acids produce colors, as in “Susurra el moro” (“The Moor’s Whisper”), 2008, left. Right: Julio Juste’s “Baño Árabe” (“Arab Bath”), 1988, from his series “Castillo Inferior” (“Lower Castle”), inspired by the Alhambra’s hammam (bath), is a collage of paper, cardboard and wood that recalls the ephemeral nature of the modest materials Nasrid artisans used in building the Alhambra. |

Juan Manuel Brazam, another Granada artist established both in Spain and internationally, says that if he were born in any other place, while he might be the same physically, his work would be different. His canvases, he says, are more and more nurtured by the art of al-Andalus, the Nasrid kingdom and the Alhambra. He builds his paintings with “the transparency of its light, the sound of water, the play of its jets of water.” The images of its mosaic inlays, he says, call forth unity, abstraction and geometry.

Maria Teresa Martín-Vivaldi, painter and engraver, has used the Alhambra in a series of works that impose color and perspective on the vaults and tiles, creating a dream-like vision in which the monument appears, blurs, and dissolves. Asunción Jódar finds inspiration in the private worlds of the Alhambra’s female dwellers, which “excludes or cancels out any outlying or simplistic, exterior observation.”

The proliferation of paintings based on the Alhambra continues among younger Granada artists, the “emergent” ones, who always seem to bring forward renewed visions no matter how impossible it may seem to do so anymore. Belén Esturla, Silvia Abarca and Leonor Solans all capture new looks with new shades of light through their treatments of color. Augusto Moreno, born to a Granadan family of sculptors, works with copper sheets in which colors appear through the actions of firings and acids—not unlike the tradition of glazed pottery. José Javier García Marcos uses color with a fury that pulls him halfway toward an Abstract Impressionism.

|

| (2): courtesy of the artists |

| Left: One in a series of sketches called “La Alhambra,” published in 2007 by Miguel Rodriguez-Acosta, abstracts and almost pixellates colors and patterns, as does “Rincon de la Alhambra” (“Corner of the Alhambra”), 2010, by José Manuel Darro, right. “Even though the Alhambra has been painted almost to saturation as a picturesque, exotic subject or as a landscape, it has been much less common to recreate the language and the geometry of its fragments,” says Darro. “I have approached my works with a certain determination in this formal universe.” |

Departing from the widespread definition that art embraces all creations made to express a sensitive vision, we can see how the Alhambra is far more than beautiful architecture, far more than the vegetal intricacies of the arabesques on its walls. It speaks more than the words of its Kufic calligraphy; the reflections of the waters in its fountains and ponds reflect more than its own parapets and the bright Andalusian sky. The real power of the Alhambra palace lies not only in its own masterpieces, but also in its power to fire creativity beyond itself, beyond its time, beyond its place, in the far greater garden of the human imagination.

Those who gaze upon the gardens and palace that beauty adorns indeed begin to know their being—their essence—as the poet Ibn Zamrak immortalized on the wall of its Hall of the Two Sisters. It is an essence not known as we know fact, but apprehended, as so many artists have shown, in the way we know a truth, or even an epiphany. And then, the Alhambra itself becomes the artist, working on us.

|

Ana Carreño Leyva (acarrenoleyva@gmail.com) is founder and former editor of the Spanish cultural magazine El Legado Andalusí and former communications director for the Fundación El Legado Andalusí in Granada, where she has also curated numerous exhibitions. In 2007, she translated The Hermetic Alhambra (Port-Royal Ediciones) by Antonio Enrique. A painter by avocation, she remembers the first time her parents took her to the Alhambra as a child. “It was like entering a world of magic and dreams, and I saw it through the eyes of my imagination.” |