|

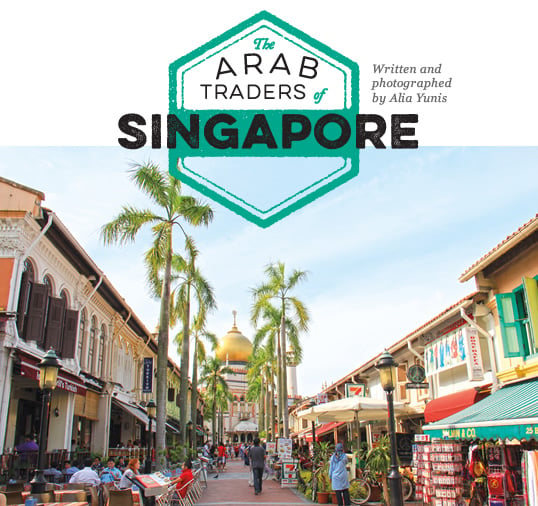

| Restaurants and traditional shophouses line Boussora Street in Singapore’s Arab Quarter, anchored by the Sultan Mosque. |

The World Bank ranks Singapore as the easiest country in the world in which to do business. Indeed, business is what brought the Alattas, Aljunied, Alsagoff, Alkaff and Ibn Talib families here in the early 1800’s, in one of history’s most successful Arab Diasporas.

|

| Just down the street, members of the Arab Network of Singapore meet at Zac’s Cafe. Alwi Abu Baker Alkaff sits center, a picture of his community’s Hadhramaut homeland in Yemen behind him. |

For much of the 19th century and into the 20th, the Arabs of Singapore owned more than 50 percent of the 710-square-kilometer (275-sq-mi) island territory. But that was a long time ago, before Singapore became the second-most densely populated country in the world and the one with the highest per capita percentage of millionaires: 15.5 percent of its 5.4 million inhabitants—837,000 people. Before it evolved from a backwater trading post into the most technologically advanced country on the map, a gleaming city-state metropolis of skyscrapers and upscale shopping centers. And before its Kampong Glam district (sometimes called the Arab Quarter) metamorphosed into the trendy, hipster place to hang out that it is today.

Five and six generations after their ancestors arrived, there are many Arabs who haven’t forgotten their roots. Quite the opposite: Their forebears came from Hadhramaut, in southern Yemen, and the members of this tight-knit community still identify themselves as Hadhramis, Arabs and Muslims—but firmly placed in Singapore.

“When we were children, my father used to say, if we were naughty, ‘I’ll send you to Hadhramaut,’”recalls Khadijah Alattas, a soft-spoken businesswoman, at a Saturday afternoon gathering of several women and a few men who belong to the Arab Network of Singapore (ans), a group formed a few years ago to develop cultural events to benefit local charities.

The others at the table laugh and nod at Alattas’s comment. Yet their pride in their heritage shows as they compete to tell each other the stories of their own families. Most would like to visit Hadhramaut one day, although none wants to go back permanently. The young women vigorously shake their heads and say “no” with a smile when asked if they would marry someone living in Hadhramaut. Still, by family pressure in the past and by choice today, they rarely marry outside Singapore’s Arab community.

|

| Mary Evans Picture Library / AlamY |

| This engraving of Singapore Harbor was made around 1870, when Singapore’s Arabs owned more than half the island’s territory. They began arriving in the early 19th century, and they have not forgotten their families’ roots in southern Yemen. |

The group is meeting in the Arab Quarter at Zac’s Café, several metro stops away from the city’s financial district where Alattas, the de facto ans leader, works. Zac’s is a Middle Eastern restaurant decorated with wall-sized photos of Hadhramaut’s mountainous landscape. From its open windows, the café offers a good view of the Sultan Mosque, Singapore’s largest and the only one with a call to prayer that can be heard outside its walls.

Near the mosque runs Muscat Street. Two years ago, the ans took part in its grand reopening that celebrated the completion of a joint project by the governments of Singapore and Oman to revitalize the thoroughfare, which now includes two ornate archways and a series of four murals depicting Singapore’s Arab heritage.

Zac’s Café is one of many “shophouses” in Kampong Glam. Shophouses were once the domain of Arab merchants and traders, structures in which the bottom half was reserved for retail commerce and the top half was the family abode. Today they are a prime destination for tourists looking for batiks, fabrics and perfumes or a sidewalk café to smoke shisha day or night in the steamy outdoors. But only four of the shophouses on Arab Street are still owned by Arab families.

|

One of them, Aljunied Brothers, is a Chinese and Malay clothing-and-tailoring shop still run by Zahra Aljunied’s 85-year-old father, Junied. Zahra Aljunied is a fast-talking librarian with more stories than time to tell them, and she is well known for organizing the first exhibit about the Singapore Arabs, which opened at the National Library in 2010 and included personal papers, photos and artifacts. Keeping family trees is traditional in the Hadramaut community, and she has continued the work of her grandfather, whom she calls “the Aljunied genealogist.” Unlike others in the community, she has visited Yemen twice with her father, mostly to work on her collection.

At Zac’s, the women crowd around Aljunied’s computer as she shows old photos she has collected. Many are surprised by the pictures. When she pulls up a black-and-white photo from the early 1950’s of several women in glamorous evening gowns, one of them shouts: “That’s my grandmother!” Her grandmother, it turns out, is also an aunt to one of the other women, and the cousin of another. But there are no striking family resemblances among them. Hadhrami traders traveled far and wide in Southeast Asia starting in the 1500’s, and they married members of other ethnic groups over the centuries. Many of their descendants’ features reflect the mix of the other communities that make up Singapore, particularly the native Malay.

The Aljunieds and other major Arab business families had a large presence in Southeast Asia for nearly 300 years before they came to Singapore, from their base in Palembang, Indonesia.

Legend has it that Singapore got its name from a Malay prince who landed here in the 13th century and saw a lion: in Malay, Singapoura means “Lion City.” When Britain colonized the “Lion City” in 1819, there were already some Arabs here. But it was Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, the designer of “modern” 19th-century Singapore, who encouraged many more to come, the better to fulfill his ambition to make the island a major regional trading hub. The Arabs made their homes in the then-Malay fishing neighborhood called Kampong Glam: Kampong means “village” in Malay and Glam is a local tree that once grew there.

|

| Arab Street, a popular venue for tourists, offers sidewalk cafés with shishas and shops with a variety of locally made products. |

“The way Singapore history is written, [the authors] give the impression that Raffles liked the Arabs,” says Syed Farid Alatas, a professor of sociology at the National University of Singapore and the ans authority on the history of the Hadhramis. “Actually, Raffles didn’t like the Arabs. He had nasty things to say about them. But he looked to the Arabs to bring this strategic location to life.

“When Raffles came, there wasn’t much going on here. He wanted to create trade networks, and the Arabs were already known throughout the region for having good trade networks. He found them useful. So he facilitated them coming to Singapore…. He used them to his advantage—like any good colonial ruler would do.”

Singapore’s most iconic building is the colonial-era Raffles Hotel, which rose on land leased originally from the estate of Syed Mohammed Alsagoff in 1887. Indeed, property-leasing was the biggest business of the Arabs until the 1950’s. But that changed when the government instituted policies that still cast a shadow over the community’s conversations.

Most of the Arab properties were traditionally held in Muslim trusts called waqfs. Under the Rent Control Act in 1947, however, the owners of all pre-World War ii buildings—and thus most waqf properties—were barred by the government from raising rents to keep up with inflation. Consequently, the value of the trusts diminished significantly. But the biggest blow came with the 1967 Land Acquisition Act.

As Singapore’s government began to envision the island’s further transformation into a global business center, the shortage of land for urban development became acute. The act allowed the government to aquire any property—particularly prewar property—for urban renewal at whatever price it determined.

|

| John Harper / Corbis |

| In Singapore in the early 1800’s, the British aimed to make the island a strategic hub for commerce; their success carries on at Singapore’s vast container ports today. |

That meant the Arabs, who owned much real estate in central Singapore, had to give up properties at prices much below market value. Indeed, only one major property remains in Singaporean Arab hands: the Treetops Executive Residences, a luxury apartment complex on the outskirts of the city center where a private villa of the Talib family once stood. It was converted to apartments in 1953 and then demolished to make way for Treetops in 2000.

Khaled Talib, a journalist and author whose grandfather bought the Treetops land with his brothers in the 1800’s, notes that his family also suffered losses of land due to the Land Acquisition Act. “We had more than 600 shophouses in Singapore, and today we only have about 40,” he says. “Some we sold [at market value], but many were acquired.”

In addition, he explains, “most of the land in Singapore owned by the Arab families came under mandatory legal-trust management, which has now expired. As a result, the properties were sold and shares of inheritance divided, apart from being subject to land acquisition. Our trust, on the other hand, is ongoing. We were also quick to adapt to changing times by ensuring that our properties were refurbished in order to match the changing landscape of Singapore.”

|

| The bride’s accessories highlight her Arab heritage in this Singapore wedding photo from the 1930’s. A member of the Alsagoff family, she hailed from Makkah, where it is likely that her father was a trader. |

Many Arabs also did a poor job of record-keeping, as Zahra Aljunied knows only too well. “I found a letter dated 1954 from the British Government to my father telling him it needed a piece of his land to build a religious house, and promised him a 100-year lease,” she says. “He assumed it was a mosque, but they built a church there.” Worse than that misunderstanding, she says, she cannot find the lease he signed—no one can—so the land has been permanently lost to the family.

These stories are not part of the general conversation in Singapore, however. Tan Pin Pin, a local filmmaker who explores the less-flattering sides of Singapore, including a short film on the complications of land shortages, knows little about the Singapore Arabs, but she is part of a younger generation that is interested in knowing more about the country’s heritage.

“My great-grandfather came here from China in the late 1890’s,” she says. She pulls out her national id card, which shows she is ethnically Chinese. (The categories on the card are Chinese, Malay, Indian and Other.) “These categories make it easy for the administration to control business and to keep the [ethnic] proportions in place for stability,” she says.

|

| The Aljunied Brothers parfumerie on Arab Street is one of the few remaining Arab-owned stores in the Arab Quarter. Their shop also features batik clothing and accessories. |

The Arabs, who estimate their numbers at between 7,000 and 10,000, fall under “Other.” But Alatas says their actual numbers would be higher if many hadn’t chosen to call themselves Malay when the government started giving education subsidies to Malays, who are considered the official native people.

“In the 1980’s, the government actually began to encourage the different ethnicities to develop their own identities,” he says. “I suppose it’s because the government thought it was a good sell for tourism. It’s part of developing the multicultural side of Singapore, and that also has had an effect on the different ethnic groups becoming more interested in their heritage.”

That kind of encouragement helped spur the founding of the ans. A gala dinner it hosted last November to support local charities received media coverage that inspired the group to do more. “We want to showcase our culture and at the same time prove that we are an effective and productive part of Singapore,” says Khadijah Alattas.

By the 1980’s, Singapore Arabs were rarely going back to visit Yemen. Homecomings had already begun dropping off in the 1960’s as Yemen became more politically turbulent. In addition, in 1967 Singapore instituted mandatory military service, with the result that young men who traditionally would visit Yemen in their late teens no longer could. If Singapore Arabs leave today, it is mostly to immigrate to Australia to work.

By the 1980’s, Singapore Arabs were rarely going back to visit Yemen. Homecomings had already begun dropping off in the 1960’s as Yemen became more politically turbulent. In addition, in 1967 Singapore instituted mandatory military service, with the result that young men who traditionally would visit Yemen in their late teens no longer could. If Singapore Arabs leave today, it is mostly to immigrate to Australia to work.

Nor can the Hadhramaut region count any longer on remittances from Singapore-based relatives, who once built grand homes there. Still, the Singapore community enjoys the little ways in which its members have influenced Yemen’s culture: For example, the prawn crackers and fish paste that are common in Yemeni cuisine came from Singapore’s Malay cooking.

On the other hand, as Singapore itself has become an international foodie haven, its Arabs have done little to promote their traditional cuisine outside their homes, as Arab immigrants have done in the West. Few of them speak Arabic either, aside from endearing traditions like still calling women sharifa—a name meaning “noble.”

Their strongest bonds are genealogy and religion. Many families trace their lineage back to Mohamad bin Isa Al Muhajir, a 10th-generation descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, who moved from Baghdad to Hadhramaut in 956 ce. Today, most of the families in the community help their children with religious studies at family gatherings on Friday evenings.

|

| Simon Reddy / Alamy |

| This statue of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, framed by the skyscrapers of Raffles Place across the Singapore River, is believed to stand at the spot where he landed in 1819, going on to establish the British settlement on the island. “He looked to the Arabs to bring this strategic location to life,” says Syed Farid Alatas. |

Imam Hassan Al-Attas comes from a long line of spiritual leaders. Over dinner at his house, where he and his wife live with their extended family, he and Syed Farid Alatas talk about the history and faith of their ancestors. “Many people say the Hadhramis came to spread Islam, but, of course, the majority of them were not doing that,” Alatas says. “There were a lot of push factors—instability, infighting and one of the most driving forces: famine.

“A thousand years ago, Hadhramaut was very fertile, but in the last 500 years it has become less and less fertile, so people began to leave to look for jobs to support themselves. Since the education in Hadhramaut was basically religious, they might be traders, they might be property owners, but when they were going out and about in other countries for their work, they converted people through various ways, particularly intermarriage.”

“At the same time, there were some real scholars that came over,” adds Imam Hassan, whose family is a living example. “They came because they were being called to take certain positions as the community grew. And sometimes they were doing both—you would be a preacher, but you would supplement that with trade.”

Imam Hassan and Alatas say Singapore’s Middle Eastern street names have more to do with its strategic location than any other factor. Just as Singapore was a central spot for trade, it was also a good stopping-off point for pilgrims from Indonesia and elsewhere to the east to get supplies on the way to the Hajj in Makkah.

|

| Singapore’s Arab Quarter draws an eclectic mix of visitors and locals, day and night. The descendants of its original Arab residents still celebrate their heritage, but mostly live elsewhere in the city. |

Hassan notes that his father built his own mosque here in 1952, before the government rationalized mosque construction by regulating funding and issuing building permits based on neighborhood populations.

“Singapore changed so much in my father’s lifetime,” he says. “He had three passports—British, then Malaysian and then, when Singapore separated from Malaysia [in 1963], a Singapore one. The only thing that didn’t change was that he was Hadhrami. I remember that my father would give his sermons in Arabic. And there would be Malays there, especially during the Friday prayers, who wouldn’t know Arabic.”

Since the 1970’s, after the formation of the Muslim Religious Council, every Muslim employee automatically donates one Singapore dollar from his or her salary every month to pay for mosque construction. “When there is enough money, the government gives it to the religious council for one of the Muslim communities, could be Indian or Malay, to build their own mosque,” Imam Hassan says. “Some of the mosques in the old days were made of wood. Now they are more beautiful and have all the modern facilities.”

Nearly everything about Singapore is very modern, even the relatively old. Ethnic enclaves like the Arab Quarter are neat and orderly, just like the rest of the city. It is a diverse tourist spot from morning to night, but the descendants of the original inhabitants of this neighborhood mostly live somewhere else among the shiny towers and pristine, tree-lined streets and gardens of modern Singapore.

They work in professions that define the country’s business image, as professors, diplomats, bankers, writers, secretaries and, yes, still occasionally shophouse owners. They are as comfortable walking along Orchard Road and Singapore’s other sleek boulevards or strolling near Marina Bay—where the city’s Merlion (half lion-half mermaid) statue serves as a mascot and tourist attraction—as they are listening to the call to prayer on Arab Street.

“There is no such thing as a Singaporean wholesale,” says Khaled Talib, summing up the complexity of the Singaporean identity. “I was once in the uae for a year, and I tried to join the Singapore Club. When I spoke to the head of the club on the phone, a Chinese person, he didn’t believe that I was from Singapore. As you can see, his version of a Singaporean differs from mine. So I like to classify myself as a Singapore-born Arab, a houseguest of the Malay people, the original owners of the land.

“And at home, we still make halwa and muhalabiyyah for dessert. Some things have not changed.”

|

Alia Yunis (www.aliayunis.com) is a writer and filmmaker based in Abu Dhabi. She is the author of the critically acclaimed novel The Night Counter (Random House, 2010). |