|

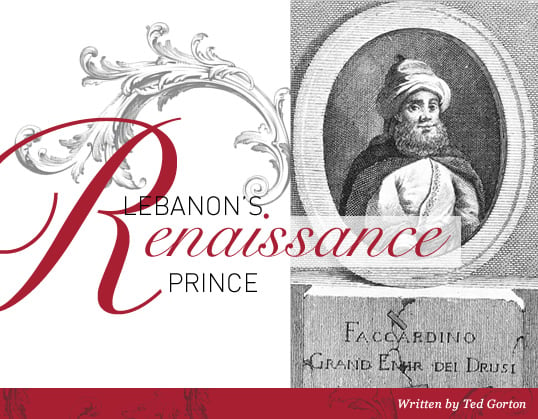

| giovanni mariti, istoria di faccardino, grand-emir dei drusi (frontispiece). |

| This 1787 engraving is the only known portrait of Amir Fakhr al-Din Ma’n that appears to agree with written descriptions of him. |

Like all countries, Lebanon has national stories about its origins. In them, Amir (Prince) Fakhr al-Din Ma’n is both colorful and controversial. Born in 1572 and executed for treason in 1635, he is a “father of the nation” to generations of schoolchildren, even “founder of the modern Lebanese state” to one writer (Aziz al-Ahdab), while, more recently, historian Kamal Salibi downgraded him to a mere “strongman” whose contributions to the modern state were incidental to his dynastic concerns. But both views underplay the role of his travels to the West in a time when few Arabs did so—-even if forced by circumstance.

is early life was marked by trauma: In 1585, when he was 13, the Ottoman governor of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha, led an army to the Shouf Mountains of southern Lebanon, where his forebears of the Druze house of Ma’n had ruled since before the 1516 Ottoman conquest of Syria. Ibrahim’s orders were to punish the frequently rebellious Druze, who by that time were chafing at Ottoman control. Fakhr al-Din’s father, Amir Qurqmaz, was killed, along with hundreds of others. The boy found himself a sudden heir to the leadership of a devastated realm, surrounded by hostility.

is early life was marked by trauma: In 1585, when he was 13, the Ottoman governor of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha, led an army to the Shouf Mountains of southern Lebanon, where his forebears of the Druze house of Ma’n had ruled since before the 1516 Ottoman conquest of Syria. Ibrahim’s orders were to punish the frequently rebellious Druze, who by that time were chafing at Ottoman control. Fakhr al-Din’s father, Amir Qurqmaz, was killed, along with hundreds of others. The boy found himself a sudden heir to the leadership of a devastated realm, surrounded by hostility.

Against the odds, and with help from his mother and younger brother Yunus, he gradually restored his family’s power through commerce, warfare, marriage, tributes and other means. By the time he was a young adult, the Ma’n had reasserted control from Beirut east to Palmyra and south as far as Galilee.

Throughout these years, England, France and Spain, as well as principalities of the Netherlands, Genoa, Venice and Tuscany, competed for eastern Mediterranean trade while the Ma’n and others in Lebanon and Syria competed with each other and their Ottoman overlords. It was this network of competition that in 1608 led Ferdinando i de’ Medici, grand duke of Tuscany, to sign a treaty with Fakhr al-Din. For Tuscany, it strengthened its hand against rivals Venice and Genoa, and for Fakhr al-Din, it strengthened his position under Istanbul—which had granted the French “Concessions” that gave them exclusive rights to trade in Ottoman ports. Keenly aware of the treaty’s potential to rankle, it included a provision assuring Fakhr al-Din asylum at the house of de’ Medici should Istanbul come to object too strongly.

In 1610, Oxford scholar George Sandys visited Lebanon and wrote the first known personal description of Fakhr al-Din, whose fortunes were rising:

Small of stature, but great in courage and achievements: about the age of forty [he was 38]; subtill as a foxe, and not a little inclining to the Tyrant. He never commenceth battell, nor executeth any notable designe, without the consent of his mother.

Other sources during his lifetime also noted that he was short, stocky, strong, cheerful and noble but unpretentious; with clear, bright eyes, a pug (or at least non-aquiline) nose and a dusky complexion; an accomplished chess-player and horseman with interests in botany and astronomy. (He was so small that his archenemies in Tripoli, the Sayfas, were said to joke that “an egg could fall from his pocket without breaking.”) Fakhr al-Din was furthermore unanimously portrayed as fearless in battle; generous to all and merciful toward vanquished enemies; true in friendship; popular with the common people; just in government but implacable and even harsh in justice.

The banu Ma’n & the Druze

Three years after Sandys visited, Fakhr al-Din pushed Istanbul too far. His son ‘Ali defeated a troop of elite, Damascus-based Janissaries at Muzayrib, near the modern Syria-Jordan border. To the Ottomans, it signaled an unacceptable expansion of Ma’n influence. At the same time, a lull in conflicts with Persia allowed the Sultan to dispatch an army to retaliate—and probably more.

Recalling the punitive expedition that killed his father in 1585, Fakhr al-Din held a council meeting in Sidon in mid-September 1613: The choice was to fight to an almost certain death or flee, in the hope that Tuscany would honor the terms of the five-year-old treaty. Just before the Ottoman army closed in, Fakhr al-Din and a hundred or so followers took to three ships, one Dutch and two French. The companions he chose were a remarkably mixed group for the times: Druze, Sunni Muslims (including his chief counsellor, Hajj Kiwan), Maronite Christians and two Jews (including Isaac Caro, his friend and secretary). Also aboard was his wife Khasikiya and their infant daughter.

Their destination: Livorno, principal port of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, on the northwest side of the Italian peninsula. Ferdinando i had died a year after the treaty, and he had been succeeded by his son, Cosimo ii.

|

| bridgeman images (detail) |

| Though he died a year after signing his treaty with Fakhr al-Din in 1608, Grand Duke Ferdinando i de’ Medici of Tuscany saw the Amir as an ally in maritime commerce that bypassed Turkey. |

The voyage took more than 50 days, and it was imperiled by storms that caused the French ships to arrive three days after Fakhr al-Din’s, as well as by pirates whom the crews dissuaded with threats of “cannonballs and fight.”

On Fakhr al-Din’s arrival, the 23-year-old Grand Duke Cosimo ii was in Florence, attending one of the earliest performances of what we now call opera. Fortunately, his mother and Ferdinando’s widow, the Archduchess Cristina di Lorena, was there. A few days later, Fakhr al-Din and his entourage were accorded a royal reception at the Palazzo Pitti, hailed by the Archduchess as “beloved of my late husband.”

And so began an extraordinary, five-year sojourn. The de’ Medici were pleased to host an exile who offered a prospect of lucrative markets should his restoration to power be made possible. Fakhr al-Din and his companions were thus among the very few non-Christians from the Ottoman Empire to voluntarily reside in the Christian lands of Europe. The rarity of such contacts was a product of the times, for the Ottoman-controlled Levant tended to be more welcoming to Christian travelers, traders and pilgrims than was Europe to Muslims and Arabs.

Much of what we know of this part of Fakhr al-Din’s life comes from the chronicle of Ahmad al-Khalidi al-Safadi, who may have accompanied the Amir in exile or, more likely, took dictation from him after his return to the Shouf in 1618. It is a unique view of Renaissance Europe through a Levantine lens, a mix of practical and social observation:

We were told that the Duke’s daily income was eighty thousand scudi, but others said that was the gross revenue of his country, not all of which belonged to him. We also heard that he had annual revenues of [a million gold piasters]. Apparently his dynasty is not very old, dating back a century or so to the year 900 of the hijra [October 1494; the Florentine Republic was founded in 1532]. Their family were originally physicians [“Medici” means “doctors”]….

Fakhr aL-Din on the Stage

In the heights above Florence, the Duke has a vast and imposing villa surrounded by gardens and water.… There are iron water-pipes buried in places under the garden, and whenever they wish to play a joke on someone entering it, they turn the water on suddenly so that it squirts on him from top to toe.… Their purpose in building such palaces with their gardens is to have different places to spend about three months at a time, along with their families. Thus they spend the three winter months on the coast, the three summer months in the hill-country; the three months of spring are spent in-between, where the hunting is good, and so it goes for the autumn as well.

Their domains are orderly, prosperous and disciplined; the title Gran Duca means in Arabic the “Great Amir” or “Prince,” for in the lands of the Christians there are many principalities. This Duke is said to be greater than any of the others, for all the kings and Sultans of the Christian lands write to him and show him all due respect.

Indeed, there was time for leisure as well as business. This is how al-Safadi described Florence on the eve of Carnival, 1614:

At that time began the feast of Carnival which falls just before their long period of fasting [Lent]. They celebrate it with various games and amusements, covering their faces with masks dyed in different colours. They fill hollowed-out eggs with rose-water if they are rich, plain water otherwise, and throw these at each other; grown-up men do this with each other and even with women. They attach a helmet to a stake; the horsemen have to gallop by at full speed and strike it with a lance, which they hold from the bottom since there is a pennant on the tip—which has no sharp point, but a piece of lead which is used to mark the place of impact on the helmet. The clever horseman who strikes the helmet on the eyepiece gets the prize….

At night they have other games and dancing for men and women together, in a huge hall, with the far wall decorated with tapestries of landscapes that look very far away, with the sky red as sunset and figures passing across it like angels. On the floor there are rollers underneath sea-blue cloth that move up and down, imitating the waves of the sea, while a skiff sails quickly across it; about fifteen handsome youths jump out, dancing and reciting speeches….

|

| abraham storck / rafael valls gallery / bridgeman images |

| This view of the harbor at Livorno, the main port of Tuscany, was painted a few decades after Fakhr al-Din’s exile. |

De’ Medici accounts of the Amir are less vivid, although the de’ Medici agent who received Fakhr al-Din for a visit to Pisa said he was “exceedingly curious about all the customs and practices found in Christendom.” As his daily business, Fakhr al-Din tried to drum up European support for his return to power, even going so far as to propose an invasion of the Levant, with him at the head of an army backed up by European naval and logistical support. His meetings with the Grand Duke, the French ambassador and indeed Pope Paul v Borghese were attended by de’ Medici translators. The most tantalizing political prize of all for his Christian allies would have been no less than the recovery of Jerusalem from Ottoman control. But he was too late by at least a century: European enthusiasm for crusading had given way to commerce and the tensions that would bring on the Thirty Years’ War.

After two years in Tuscany, he accepted an invitation from the Spanish Viceroy of Sicily—the Duke of Osuna—to come to Messina. Like the de’ Medicis, Osuna hoped the Amir could be useful in furthering his commercial ambitions in the Levant; the Amir hoped the Spanish would be more effective at securing his return to power than the de’ Medicis had proved to be. A year later, Osuna was promoted to Viceroy of Naples; again, Fakhr al-Din and his suite tagged along, unable to return home while his enemies held sway in Istanbul. He stayed there the better part of two further long years, dreaming of—and lobbying for—a grand invasion that would put him on the throne of Syria.

He became homesick, notably for his aging mother, who with his brother Yunus had successfully managed the home front, protecting the Ma’n family and supporters from reprisals.

|

| left: jacopo da empoli / palazzo comunale / bridgeman images (detail); right: justus sustermans / galleria degli uffizi / bridgeman images (detail) |

| Left: Cosimo ii de’ Medici was 18 years old when he succeeded his father as grand duke; his tutor was Galileo (who later, like Fakhr al-Din, received sanctuary at the House of de’ Medici). Right: Cosimo ii appears at center between his wife, Marie Madeleine of Austria and his son Ferdinando ii. |

In late 1618, his fortunes brightened with the execution of his archenemy, grand vizir Nasuh Pasha, which was followed by a letter from rising star Ali Pasha, a longtime personal ally who became grand vizier a year later. Ali invited the Amir to return and receive the title of Governor of Sidon, Beirut and Jubeil. Fakhr al-Din set about to depart at once, as related by al-Safadi:

Some counsellors of the Duke told him that it was unwise to let Ibn Ma’n return to his country, having observed and learned so much about the Christian lands. So the Duke hesitated to provide the ship with written permission to sail, it being their custom that no ship may sail without one.

All the Emir’s family and his followers and possessions were on the ship, and this situation continued for eight days. Finally the Emir invited the Duke’s interpreter, one Carlo, onboard the vessel. While he was onboard, the Emir had a barrel of gunpowder which he had purchased brought up, had his wife sit on it, and told the interpreter: “If the Duke obliges us to disembark, meaning that we shall have no hope of returning home with our women and children, if we despair of the Duke’s decision, we will set fire to the gunpowder and blow ourselves up, women and children and all.” The Emir then went ashore and told the Duke his last word, as follows: “It was with your permission that we embarked on this boat, along with our families and possessions. Now we have been there for eight days, suffering from the heat at a time of Ramadhan fasting. I demand a permit to sail!” When the Duke’s wife heard this, she told her husband, “Since you gave them permission to embark, you gave them your word, you must give them permission to sail, along with their families, who are already onboard the ship.” The Duke said, “All right, come tomorrow and receive the permit…” The Emir came to see the Duke to thank him before they sailed, which they did in the middle of Ramadhan, in the year one thousand and twenty-seven of the Hijra [September 6, 1618].

Fakhr al-Din spent the decade or so after his return consolidating the power of the Ma’n, building and repairing defensive and civil structures and working for the economic growth of his realm that by 1625 included most of the Levant outside Anatolia, the cities of Aleppo and Damascus, and the coast from Beirut to Gaza. He had learned Italian and used that knowledge to translate treatises on botany, one of his hobbies.

Fakhr al-Din spent the decade or so after his return consolidating the power of the Ma’n, building and repairing defensive and civil structures and working for the economic growth of his realm that by 1625 included most of the Levant outside Anatolia, the cities of Aleppo and Damascus, and the coast from Beirut to Gaza. He had learned Italian and used that knowledge to translate treatises on botany, one of his hobbies.

As trade grew, despite the official monopoly granted by the Sultan to France, Fakhr al-Din continued to receive gifts from the de’ Medicis. The choice of gifts reflects more than mere political intent: the Medici Archives in Florence mention much silverware, jewelry and, perhaps most notably of all, “a telescope of Galileo, long, with its wooden case.” These were the years during which Galileo was resident in Tuscany under the protection of the de’ Medicis, at Villa Bellosguardo.

Fakhr al-Din and the Historians

Fakhr al-Din built a palace in Beirut and another in Deir al-Qamar, a castle at Palmyra and a khan (market-hostel) that still stands in Sidon. He restored the castle of the Knights of Saint John in Akka (Acre) and fortified Crusader and Mamluk forts ringing his domain from Qa’a in the northern Bekaa to Baniyas in the Golan Heights.

Nevertheless, in pursuing expansionist policies and—worse—stinting on bribes to the officials of the Porte, he eventually again pushed his Ottoman masters too far. Chronicler al-Safadi died in 1624, and most of what we know about the remainder of the Amir’s life comes from Ottoman historians such as al-Burini, al-Qaramani and Shams ad-Din ibn Tulun, all of whom took the official line that Fakhr al-Din was both a traitor and a heretic.

The tipping point came in late 1632, when an Ottoman army that had just failed to take Baghdad from the Persians sent word that it intended to spend the winter in the Bekaa Valley. Fakhr al-Din reportedly was furious at being merely informed rather than asked for that privilege—and possibly wary of having an Ottoman army wintering in his backyard. He sent a detachment of soldiers and forced the battle-weary troops to withdraw to much less hospitable winter quarters farther north, on the other side of Aleppo. Unsurprisingly, the commander complained to Istanbul, and this must have been judged a last straw. If Sultan Murad iv could not have Baghdad, he would have at least the head of an upstart Druze.

|

| ted gorton |

| This idealized wax effigy of Fakhr al-Din is on display in Fakhr al-Din’s historic palace in Deir al-Qamar, Lebanon. |

In 1633, the Sultan ordered the governor of Damascus to lead 20,000 soldiers against the Amir’s 8000. It seems that Fakhr al-Din sent his son ‘Ali north to prevent the Sayfas, his enemies in Tripoli, from linking up with the Damascus troops, but ‘Ali was killed on the mission. There was no flight to Tuscany this time: Fakhr al-Din’s troops were routed; his younger brother Yunus was captured and executed. The Amir fled to a cave, but he was captured with his sons Ma’sud and Hussein and taken to Istanbul. There, on April 13, 1635, Fakhr al-Din and Mas’ud were strangled and beheaded. Hussein was spared, having not yet reached puberty. He grew up in the Saray (Palace) and eventually became Ottoman ambassador to India.

Fakhr al-Din’s legacies are not simple ones. Ev-erything about him speaks to an absence of vindictive sectarianism: There is no evidence that he ever harmed or persecuted anyone simply because of religious beliefs or ethnic origin. He was a pragmatist whose supporters and confidants came from a mix of ethnic-religious groups that united under him in an effort to achieve a measure of local autonomy that demonstrated the potential for different communities to work together.

|

| museum of turkish and islamic art, istanbul / bridgeman images |

| By 1633, Ottoman Sultan Murad iv could no longer tolerate Fakhr al-Din’s expanding power—and the growth of European trade that went with it. |

Fakhr al-Din worked hard to introduce cultural and economic improvements based on his experience in Europe. The Italianate buildings in Beirut’s much battered Sursock Quarter and elsewhere in Lebanon owe something (though not everything) of their style to the de’ Medici palaces he had known. In a 17th-century type of technology transfer, he hired Florentines to assist with civil construction, medicine, baking and farming.

Today, a Virgin Megastore and a parking lot stand on the site of his Beirut palace that for more than two centuries was a landmark. Sixty years after his death, a touring Englishman, Henry Maundrell, described it:

The emir Faccardine had his chief residence in this place. … At the entrance of it is a marble fountain, of greater beauty than is usually seen in Turkey. The palace within consists of several courts, all now run much to ruin; or rather perhaps never finish’d. The stables, yards for horses, dens for lions and other savage creatures, gardens, &c. are such as would not be unworthy of the quality of a prince in Christendom … but the best sight that this palace affords, and the worthiest to be remember’d, is the orange garden…. One cannot imagine any thing more perfect in this kind.

The Lebanese government erected an equestrian statue of the Amir in 1974 in Baakline, his birthplace, but two years later, during the Lebanese Civil War, it was dynamited. From a “Father of the Nation” he had become a political football, revered by those anxious to emphasize Lebanese particularism and denigrated by those who see the country as part of a larger Arab nation. Yet to all, he set an example of tolerance and pragmatic cultural receptivity that is perhaps his most enduring legacy.

|

| Above, right: de agostini picture library / g. dagli orti / bridgeman images; above, left: ted gorton; Top, right: manuel cohen / the art archive at art resource; lower: museum of turkish and islamic art, istanbul / bridgeman images |

| After his return from exile in 1618, Fakhr al-Din expanded Ma’n influence. In Sidon, he commissioned the Khan al-Franj (Caravansarai of the Foreigners), above, right; in his family’s historic home in Deir al-Qamar, his palace, above, left, is a historic building. Top, right: This 12th-century citadel near Palmyra, Syria, was among several Fakhr al-Din had renovated throughout the region. |

|

Ted Gorton (www.tjgorton.wordpress.com) is an American-born writer who lives in London and the south of France. This article is based on his latest book, Renaissance Emir: a Druze Warlord at the Court of the Medici (UK: Quartet Books, 2013; North America: Olive Branch Press, 2014). |