|

| BRITISH LIBRARY / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES (DETAIL) |

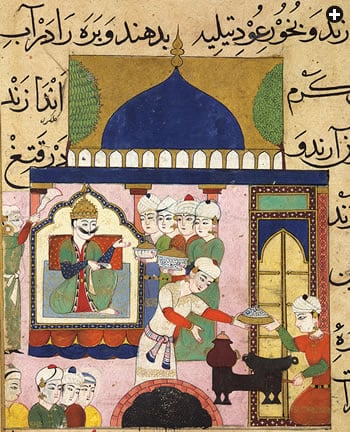

| An illustrated chronicle of recipes called the Book of Delights from the late 1400s from Mandu, India, shows Sultan Ghiyath al-Din receiving dishes prepared by his royal kitchen. Later, the Mughals created their cuisine from a confluence of Persian, Turkic and Indian elements. |

aghdad was the “crossroads of the universe,” said the first caliph of the Abbasid Empire when he founded a circular city in 762. And so it was at the time: 5000 kilometers (3000 mi) to the borders of China in the east and another 5000 to the Pillars of Gibraltar at the entrance to the Atlantic in the west. By a couple of hundred years later, a single high cuisine had been created in Baghdad, and following the intertwined Silk Roads and the sea lanes of the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, conquerors, merchants, pilgrims, religious orders and cooks had spread it across this hemispheric space. Everywhere the cuisine rested on advances in farming and food preparation and was enjoyed by the elite in prosperous cities. Never static, never homogeneous, always absorbing from and contributing to other culinary traditions, the earliest Islamic high cuisine was given coherence by a culinary philosophy that integrated religious belief with political and dietary theory. Four snapshots of the globalization of the cuisine over the past thousand years show how it spread in waves from its heartland, gaining from and giving to other cuisines of city dwellers, nomads and those of different faiths until today, when its ripples have touched almost every corner of the inhabited globe.

aghdad was the “crossroads of the universe,” said the first caliph of the Abbasid Empire when he founded a circular city in 762. And so it was at the time: 5000 kilometers (3000 mi) to the borders of China in the east and another 5000 to the Pillars of Gibraltar at the entrance to the Atlantic in the west. By a couple of hundred years later, a single high cuisine had been created in Baghdad, and following the intertwined Silk Roads and the sea lanes of the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, conquerors, merchants, pilgrims, religious orders and cooks had spread it across this hemispheric space. Everywhere the cuisine rested on advances in farming and food preparation and was enjoyed by the elite in prosperous cities. Never static, never homogeneous, always absorbing from and contributing to other culinary traditions, the earliest Islamic high cuisine was given coherence by a culinary philosophy that integrated religious belief with political and dietary theory. Four snapshots of the globalization of the cuisine over the past thousand years show how it spread in waves from its heartland, gaining from and giving to other cuisines of city dwellers, nomads and those of different faiths until today, when its ripples have touched almost every corner of the inhabited globe.

|

| Left: TODD COLEMAN; RIGHT: IGNACIO URQUIZA |

| One of many dishes that evoke the historic reach of Islamic cuisine is tharid, or bread moistened with broth, left (shown here in a modern variant with potatoes). By tradition a dish favored by the Prophet Muhammad, it became part of the first Islamic high cuisine in Baghdad, and also in Muslim Iberia (al-Andalus), where Christians replaced the broth with syrup and carried the dish they called capirotada to the New World, where it remains popular today in Mexico, right. |

1000 ce: The high cuisine of the Abbasid Caliphate

The first Islamic high cuisine, the high cuisine of the caliphate, was well established by 1000. To refine the simple cuisine of the Arabs, based on dates, milk and barley, the cooks of the court in Baghdad profited from a continuous tradition of high cuisines stretching back through a succession of Persian imperial kitchens to those of ancient Mesopotamia. Its physicians drew on the most advanced dietary theories, those of Galen in the Roman Empire and Caraka and Susruta in India. Healthful eating was one and the same as delicious eating. High cuisines were right and proper for rulers who cared for their realms as gardeners cared for their domains. Food, like the other worldly pleasures, drink, clothes, sex, scent and sound, was believed to be a foreshadowing of Paradise. It was the greatest of them all, said the author who at the end of the 13th century compiled the collection of recipes now known as the Baghdad cookbook, because, he asserted, without food none of the other pleasures could be enjoyed.

The high cuisine was enjoyed in Damascus, Aleppo, Cairo, Palermo in Sicily, and Córdoba, Seville and Granada in Spain—all Muslim by 1000. At the end of the 10th century, the first surviving cookbook in Arabic, the Kitab al-Tabikh (Book of Dishes), had been compiled by Ibn Sayyan al-Warraq as a record of the cuisine of the Caliph of Baghdad and his courtiers. Five others remain from the 13th century, and yet others are attested to, more cookbooks than anywhere else in the world at that time.

In the cities, watermills ground wheat into flour. Sugar refineries evaporated the juice of sugarcane, a plant introduced from India, to make several grades of sugar. New methods of distillation created aromatic essences of rose petals and orange blossoms. Oil was pressed from olives, as well as from sesame and poppy seeds. Egg production, sausage and preserved meat preparation, butter (samn), cheese, bread and confectionery were all in the hands of skilled specialists.

|

| top-Left: topkapi palace museum / bridgeman images; british library / bridgeman images (3) (details) |

| Clockwise from top-left, from top: A detail from a 15th-century page of sketches of a nomadic Mongol encampment shows a man cooking; Mongol rulers adopted much in Muslim cuisine, creating a kind of pragmatic—and tasty—“culinary diplomacy” in the lands they overtook. Three details from Sultan Ghiyath al-Din's Book of Delights illustrate other kitchen scenes: male cooks mincing meat, and female cooks using a variety of cookware and serving food onto a platter. |

In the geometrically laid-out irrigated gardens, herbs such as mint, cilantro, parsley, basil and tarragon; fruits including dates, pomegranates, grapes and several varieties of citrus; nuts such as pistachios and almonds; and vegetables including carrots, spinach, turnips and eggplant were cultivated. Farther off, farmers toiled in fields of wheat and cane. Where they did not already flourish, dates and pomegranates, rice and sugar were introduced as climates allowed, along with irrigation systems and techniques to process them.

Exotic goods were brought in by camel or by ship. Honey from northern forests was carried south by Vikings who returned with spices. Spices such as cinnamon, fenugreek seeds, turmeric, asafetida and black pepper came from India and Southeast Asia. Going beyond earlier limits, merchants sailed down the east coast of Africa as far as Madagascar, settling in the islands of Pemba and Zanzibar.

|

| national library of austria / alnari / bridgeman images |

| The fine, somewhat fanciful “Eastern” dress of the man on the left side of this 14th-century Italian illustration of sugarcane cultivation suggests the extent Europeans, up through the 1600s, experienced sugar as a luxury product of Islamic lands. |

The staple of Islamic cuisine was wheat bread baked in a pottery oven, above or below ground, called tannur, best known now by the cognate name “tandoori.” By tradition, tharid—bread moistened with broth and layered with meat—was the favorite dish of the Prophet. Flour was used in multiple other ways: mixed with water and used fresh or dried as pasta; rolled into dough to stuff with meat; mixed with water to make a soothing drink; or, in North Africa and al-Andalus, in coarse form rolled into tiny balls that became known as couscous.

Rich sauces accompanied roasts or bathed stews of lamb, mutton, goat, game and poultry, or, in al-Andalus, rabbit. Often these were sour or sweet-sour. Usually they were aromatized with spices, herbs and essences, seasoned with murri (a condiment made of fermented barley), colored with turmeric and saffron, pomegranate seeds and spinach, or strewn with sugar crystals that sparkled in the light. Sikbaj, which appears in all the cookbooks, was meat of some kind (and later fish) soured with vinegar; harisa (not to be confused with the Moroccan spice mix) was a puree of grains and meat; and in al-Andalus, meatballs and stews of mixed meats were popular. Most prestigious was chicken roasted over a pudding that caught the rich drippings.

High, Low and Middling Cuisines

Sweet dishes were made with honey where its flavor added to the dish. Where its aroma and color were not required, sugar was used, retaining the taste of fruit preserves, letting the rose, green or orange tints of fruit sherbets shine, keeping sweet starch or ground-nut drinks dazzling white. All could be scented with rose petals and orange blossoms. Confectioners discovered that when boiled for varying lengths of time and then cooled, sugar became successively clear and pliable, then transparent and hard, and then brown aromatic caramel, opening a myriad of culinary possibilities. Al-Warraq’s cookbook included recipes for 50 sweets, including pulled sugar, marzipan in a pastry shell (lanzinaj), syrup-soaked pastry fritters or fine white noodles, and pancakes filled with nuts and clotted cream. Jams, jellies, boiled-down fruit juices (rubb) and syrups (julab) straddled the boundary between cuisine and medicine, as did cooling drinks of sweetened diluted fruit juices (sherbet) and ground starches or nuts suspended in water (sawiq), later called horchata in Spanish. Prepared in extensive kitchens, the elegant meals were taken by caliphs and other dignitaries in shaded gardens where channels of water irrigated trees, flowers, fruits and vegetables.

1300: To the far reaches of Eurasia

In 1258, the Mongols conquered Baghdad and toppled the Abbasid Dynasty while in Iberia Christians pushed back the Muslim realm to the southern region of al-Andalus. Yet Islamic cuisines continued to expand their spheres of influence. By 1300, they were established in Central Asian cities such as Samarkand, Bukhara and Merv, as well as in the Delhi Sultanates in India, and they had made their mark in the Mongol Empire in China as well as in Christian Europe.

In central India, the illustrated Book of Delights, written in the late 15th century, shows Ghiyath al-Din, the Sultan of Mandu, in gardens with his female cooks. Recipes for stuffed pastries (samosa), skewered meats, tender meatballs and refreshing sherbets jostle with others for perfumes and aromatics, aphrodisiacs and medicines.

|

| stockfood / cps |

| By the 1600s, Ottoman cuisine in Turkey contributed its partiality for grilled lamb and mutton as well as the novel, ultra-thin dough phyllo, while drawing also on the older traditions of meat dumplings or pastries. This produced the savory borek, which remains popular, in many varieties, in Turkish cuisine today. |

In China, a handsomely illustrated cookbook and dietary manual, Proper and Essential Things for the Emperor’s Food and Drink, compiled in 1330 by Hu Szu-hui, the emperor’s physician in the Bureau of Imperial Household Provisioning, reveals how the Mongols adopted elements of the high cuisines of their vast empire as a form of culinary diplomacy. Cooks added an Islamic touch to traditional Mongol soups, thickening them with aromatic rice or chickpeas, or seasoning them with cinnamon, fenugreek seeds, saffron, turmeric, asafetida, attar of roses or black pepper, and finishing them with a touch of vinegar. They prepared noodle dishes in a creamy yogurt garlic sauce, similar to those still prepared in Turkey, and stuffed dumplings like the borek still found in the Middle East. They made Islamic-style sweets and drinks, including fruit punches, jams, jellies, julabs and rubbs.

To create this cuisine, the Mongols drafted Muslims (among others) to supply the court with everything necessary. Muslims milled wheat flour and oil, ran sugar refineries, prepared sweet drinks and sherbets, and (in the Persian khanate) worked in the kitchens and experimented with new varieties of rice. Blue-and-white porcelain became an export, setting off a craze for the product across the Old World.

To create this cuisine, the Mongols drafted Muslims (among others) to supply the court with everything necessary. Muslims milled wheat flour and oil, ran sugar refineries, prepared sweet drinks and sherbets, and (in the Persian khanate) worked in the kitchens and experimented with new varieties of rice. Blue-and-white porcelain became an export, setting off a craze for the product across the Old World.

Diplomats and cooks moved among the series of khanates in China, Central Asia, Persia and Russia interconnecting the cuisines. Then in 1368, their Chinese empire threatened by unrest that rebels had been fomenting for several decades and plague in the southwest, the Mongols went back to the steppes. In China, the new Ming Dynasty retained little of high Mongol cuisine except techniques for candying and sugaring foods, though Muslims, particularly in northwest China, continued to prepare a humbler Islamic cuisine. Yet round the fringes of the Mongol empires, from Russia in the west in a great sweep through to Iran and Central Asia, steamed stuffed dumplings still tell of the convergence of Islamic and Chinese cuisine in Mongol times.

To the west, Europe was prospering, cities were flourishing, and great cathedrals were pointing their spires into the sky. Dietary theory incorporating Islamic advances reentered Europe in the late 10th century in Salerno, a small town outside Naples with a famed medical school, when Constantine the African, a convert from Islam, translated Arabic versions of Galen. The Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum (Salernitan Health Regimen), a translation into doggerel verses of an 11th-century Arabic medical treatise by Ibn Butl of Baghdad, became widely disseminated. The Crusades of the 11th century offered Europeans glimpses of the glories of Islamic cuisine. Traders in Genoa, Barcelona and Venice made fortunes trading with Muslims and further disseminated their dishes. Merchants bought cooking pots in North Africa and sold them in southern Europe.

|

| national library of austria / alnari / bridgeman images; the stapleton collection / bridgeman images |

| Left: From the 1600s on, both Ottoman elements and New World vegetables entered Europe through the Balkans and Hungary and began to trickle down the social scale. Right: In Istanbul, the center of Ottoman high cuisine was the kitchen complex at Topkapı Palace, which employed as many as 1500 specialists. |

The nobility hankered after the scented, colored and spiced cuisine. Unsure where spices originated, they believed they hinted of Paradise itself. Although Christians distinguished their cuisine by the use of pork and the introduction of meatless dishes for the many fast days, they also adapted much of Islamic high cuisine. In Spain, the meat-and-broth dish tharid became capirotada, and in Sicily, dried pasta was prepared and traded around the Genoa-Barcelona network, while couscous remained on the menu in both Sicily and Spain. The pottage of mixed meats, grains and beans became the olla podrida (literally “rotten pot”) of Spain. Sikbaj took one of two forms: either fried fish, often subsequently bathed in vinegar, or poached fish (or chicken, rabbit or pork) in an acid marinade of vinegar or orange (escbeche and ceviche). Deep-fried doughs drenched in honey or sprinkled with sugar became the family of buñuelos, beignets and doughnuts eaten on Catholic festive days, particularly before the Lenten fast. Marzipan became so popular that it was claimed by several cities, including Toledo and Lübeck.

1600: Transformations in the Heartlands and the New World

By 1600, the culinary scene had changed once more. In the Middle East and India, Turkic peoples of steppe origin created the cuisines of the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires, based respectively in Anatolia, Persia and India. Much of Southeast Asia was now Islamic, as were the great cities of the African Sahel—Timbuktu, Gao and Djenné—on the southern border of the Sahara. The Spanish and Portuguese sailed across the Atlantic and the Pacific, establishing empires in the Americas and trading posts in the Indian Ocean, respectively, where they introduced their cuisine with its many Islamic elements.

|

| british library / bridgeman images (detail) |

| The sweet, cooling drink sherbet, shown served to the Sultan in this Book of Delights detail, left, was made with ice brought from distant mountains. |

In 1453, the Ottoman sultan Mehmed ii took Constantinople from the Byzantine Christians. By the following century it had a million people, more than any European city, and the empire stretched across North Africa, Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, Greece and the Balkans. In the kitchens of Topkapı Palace, a staff of as many as 1500 included specialists in baking, desserts, halvah, pickles and yogurt.

The Turkic heritage contributed a complex array of breads, a fondness for soups, a partiality to lamb and mutton that was often skewered and grilled, meats marinated in yogurt, stuffed vegetables and yogurt drinks. From the older tradition were meat dumplings or pastries, ground meat with spices, sugar confections in wide variety and sherbets. Salt and sour tastes were now separate from sweet ones; fewer fruits, less sugar and less vinegar appeared in savory dishes; spices were reduced and murri disappeared. Pilau rice, perhaps foreshadowed in the Mongol period, was not a staple like Asian steamed rice but an elaborate dish in its own right. Rice was washed, soaked, often sautéed, then boiled, drained and steamed so that the grains remained separate. Meat, nuts, dried fruits, vegetables and colorings were frequently added before steaming, and the steaming liquid was likely to be a broth enriched with fat. Other novelties included paper-thin, layered pastry now known as phyllo, and its associated savory and sweet dishes borek, baklava and kunafa, as well as sponge cakes made from semolina (coarse ground wheat) soaked in syrup. Extravagantly large, brightly colored sugar-candy figures of exotic animals such as giraffes and elephants or structures such as castles and fountains were carried by bearers or by wheeled carts on public occasions, tangible symbols of the vast wealth commanded by the Sultan.

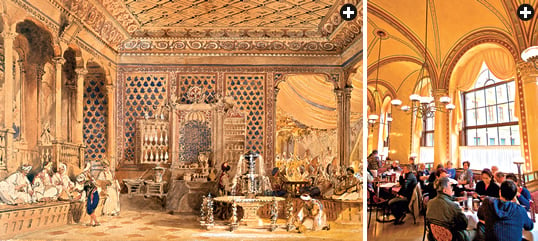

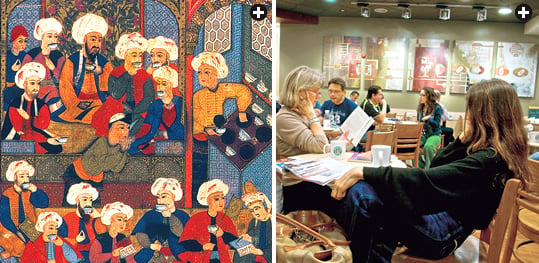

In the 16th century, coffeehouses became a place where the literati played chess and talked politics, in spite of the efforts of the authorities to suppress what they feared were centers of sedition. Coffee became the drink of the Arabic-speaking part of the Ottoman Empire: Egypt, Syria and Iraq in the east, Libya and Algeria in the West.

|

|

| arturo pena romano medina / thinkstock / getty images; kimberlee reimer / thinkstock / getty images |

| Top: Aguas frescas, popular today in Latin America, are among its close descendants. Above: Islamic nut and grain drinks became sweet horchata, widely enjoyed in Spain and Nigeria and, made with rice, in Mexico. |

Islamic elements and New World plants entered Europe through the Balkans and Hungary. Rice pilau, pita bread (lángos), phyllo (strudel), honeyed drinks and stuffed vegetables all became common in Central Europe. Turkish Hungary quickly adopted the coffee shop. Bulgarian gardeners set up on the outskirts of European cities, introducing new vegetables such as green beans, onion, chiles, cucumbers and cabbage to the townsfolk.

To the east, in 1523 Babur, a soldier of fortune of Turkic descent, led his men from Central Asia to conquer the North India plain. At its height, the Mughal Dynasty ruled about one-seventh of the world’s population. In the 16th century, Abu al-Fazl, advisor to the Emperor Akbar and steward of the imperial kitchens, described the high cuisine as part of imperial administration in the Ain-i-Akbari (Constitution of Akbar): Puffy naan flatbread was the staple, elaborate pilaus were garnished with nuts and pomegranate seeds, and meat was served grilled on skewers, in delicate meatballs and in delicately spiced stews such as lamb korma that became known collectively by the British term “curry.” Typical Islamic sweets such as fine noodles cooked in sweetened milk and deep-fried dough sprinkled with rosewater were introduced, the latter being known as gulab jamun. Ice, harvested from distant mountains and kept in ingenious icehouses, served to cool sherbets or even turn them into slushes. Other Indian courts adopted Mughal cuisine, and some of it later seeped into British cookery.

To the west in Spain, cookbooks such as the late 15th-century Libre del coch by Ruperto de Nola included recipes and ingredients that derived from Islam such as thin noodles (now called fideos), bitter oranges, fried fish, escabeche, almond sauces and almond confections. The Arte de Cocina, Pastelería, Bizcochería y Conservería (Art of Cooking, Cake Making, Biscuit Making, and Conserving) produced in 1611 by Francisco Martínez Montiño, master cook to several kings of Spain, most notably Phillip iii, contained several recipes for meatballs (albóndigas), and capirotada, and one for couscous.

The sugar cookery of Islam, introduced to Europe in the 12th century by a physician known in the literary record as Pseudo-Messue, was further developed in the mid-16th century by works such as De Secreti by Alexis of Piedmont and the Traité des Fardemens et Confitures (Treatise on Cosmetics and Conserves) of the French physician and astrologer Nostradamus. “Sherbet,” “candy” and “syrup”—the last another way of translating “sherbet” —all have Arabic roots. Comfits (sugarcoated spices) and electuaries (pastes of spices and drugs) were the distant forerunners of modern candy. Nuns created Islamic-style confectionery to sell to eager customers. Islamic fruit pastes became the Portuguese quince paste and later evolved into citrus preserves such as marmalade.

|

| thomas allom / the stapleton collection / bridgeman images; imageimage / alamy |

| English artist Thomas Allom depicted this Istanbul coffeehouse, left, in 1838, by which time coffee had grown popular throughout Europe, including Vienna, where today's Cafe Central, right, evokes a similar elegance. |

In the Americas, the Spanish vice-regal courts consulted Martínez Montiño’s cookbook. Couscous from his recipe was made at least until the 19th century in Mexico, as well as a substitute made by crumbling tamale-like steamed ground maize. A press for making thin noodles was carried to the Augustinian fortress monastery in Yuriria on what was then the frontier and is now central Mexico. Pilau rice and noodles cooked pilau style became known as dry soups (soups from which all the water had evaporated). Spicy stews and albóndigas remained popular while capirotada lost its meats and became a sweet Lenten dish. Local fruits, such as guavas, cherimoyas and mamey sapote were substituted in fruit pastes and sherbets. Housewives reproduced the soothing grain and nut drinks, now known as horchata, with rice or a variety of local alternatives.

From Mexico and from Portuguese Goa in India, nuns introduced confectionery techniques to the Philippines and South and Southeast Asia. When Jesuit missionaries entered Japan, they used the savory and many of the sweet dishes of southern Europe—and thus of Islam—as enticements to and evidence of conversion. In the Southern Barbarian’s Cookbook, a Japanese manuscript compiled in the early 17th century, a recipe for fried fish appears that would eventually evolve to become tempura, as well as confections that became known in Japanese as kompeito from the Portuguese comfeito (comfit).

Back in Europe, cooks from the south, such as the Portuguese “chief counsellor” to ladies-in-waiting who wanted to make “delicate dishes” at the court of Queen Elizabeth i of England, introduced elaborate confectionery to the north. Expensive sugar work, some of it designed to look like savory food, such as marzipan hams, sugar-paste bacon, and eggs of yellow and white jelly became fashionable, served in special “banqueting houses” on the grounds of noble mansions.

|

| chester beatty library / bridgeman images; geraint lewis / alamy |

| The bustle of another Ottoman coffeehouse, left, echoes in today’s global coffee franchises, right, which carry not only the beverage but also the original cultural associations with an urban, educated intelligentsia. |

Other Islamic elements took on their own life. Fried fish preserved in vinegar appears in the 1796 edition of Hannah Glasse’s Art of Cookery, popular in England and the us. As for the gelled juices that surrounded cold fish in vinegar, they entered European languages as aspic, still the word for a savory gelatin to encase cold dishes in high French cuisine. And julep, which the English had used for a medicinal syrup since the Middle Ages, became the “mint julep” of the American south.

More recent elements appeared too. In the 18th century, coffee vendors, often kitted out in Turkish garb, offered their wares, and coffeehouses became important centers of commerce and politics. Travelers to the Middle East returned with packages of the new starch-based sweet that they called Turkish delight.

2000: Islamic cuisines in a globalizing world

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the expansion of the British, French and Russian empires, the contraction of the Ottoman and Mughal empires, and the subsequent breakup of the European empires rewrote political boundaries across Islamic lands more than once. The globalizations of high French cuisine among the international elite and of middling Anglo cuisine among the urban middle class—the latter much influenced by the new principles of home economics—were deeply felt.

As new nations were created, many households were acquiring gas or electric stoves and, later, electric gadgets that reduced the time and labor required for complex dishes. Although many still ate (and eat) humble cuisines that depend on bread for most of their calories, middling cuisines were on an unprecedented rise. Muslims continued to be united by Ramadan and by the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Makkah. Newspapers, magazines and radio programs began to offer suggestions for dishes for Ramadan and other important festivals. Inexpensive air transport made Hajj easier. New cookbooks were written, earmarking dishes that once had been common across the broader region as more narrowly “national,” and introducing western dishes as well as the writing of recipes to reflect the scientific precision advocated by the home-economics movement, such as Ayşe Fahriye’s 1882 Ev Kadini (Housewife) in Turkey or the Usul al-Tahi (Principles of Cookery) of the early 1940s in Egypt by Nazira Nikola and Bahiya Othman, which published its 18th edition in 1988.

|

|

| CARLOS MORA / ALAMY; FOTOMATON / ALAMY; HAYTHAM PICTURES / ALAMY |

| The Abbasid vinegared fish dish sikbaj continued to evolve through medieval Spain into modern times, where it appears in varieties as distinct as cebiche, top-left, the signature dish of Peru and also popular throughout Latin America, and fish and chips, top-right, the signature dish of working-class Britain. Both are examples of high cuisine that was adapted by local tastes and resources to become popular, commonly available, middling cuisine. Above: On the other hand, aspic maintains haute cuisine status. Its name probably evolved from the Arabic word for the jelly that sets around vinegared fish, and today it is a flavored gelatin used to coat either fish or meat in French cooking. |

By the 1980s, the emphasis had shifted to the preservation of traditional dishes. In 1980 a group of professional cooks and housewives authored the Qamus al-Tabkh al-Sahih, offering traditional recipes of the region. Others followed, such as the 1990 Dalil al-Tabkh wa’l-Aghdhiya (Guide for Iraqi Cooking and Baghdadi Dishes) by Naziha Adib and Firdaws al-Mukhtar, and the Min Fann al-Tabkh al-Sa’di by Zubayda Mawsili, Safiyya al-Sulayman and Samiyya al-Harakan, which was designed to preserve traditional Saudi cuisine in the face of an influx of foreign dishes. Similarly, where once it had seemed that a tide of hamburger joints would sweep all before them, new outlets for traditional foods appeared and elegant confectionery shops held their own.

Farther afield, Latin American cuisines still show signs of the cuisine of medieval al-Andalus in their rice, their fruit drinks, their sweets and their complex spicy stews such as mole poblano, now widely taken to be one of the national dishes of Mexico. The similarities among Mexican rice, albondigas and mole poblano and Indian pilaus, meatballs and curries are clear signs that point toward common roots.

Farther afield, Latin American cuisines still show signs of the cuisine of medieval al-Andalus in their rice, their fruit drinks, their sweets and their complex spicy stews such as mole poblano, now widely taken to be one of the national dishes of Mexico. The similarities among Mexican rice, albondigas and mole poblano and Indian pilaus, meatballs and curries are clear signs that point toward common roots.

Centuries-long influences continue in other parts of the world, often unrecognized. In the late 19th century, the distant descendant of the fried version of sikbaj became the fish and chips that sustained the British working classes and became regarded by the rest of the world as Britain’s national dish. In the 20th century, the vinegared version of cebiche became the signature dish of Peru. The starch- or nut-thickened drink remains popular among Spaniards in horchaterias in Spain, is prepared in households in Nigeria and is popular across Latin America. Coffee shops, now often run as global brand franchises, continue to be places for economic and political discussion from Japan to Brazil, and everywhere they carry a connotation linking them to their roots among the intelligentsia.

Migrations at the turn of the 20th century and more recently have added newer Islamic dishes to the older medieval ones. Street stands selling meat from rotating spits served with bread and yogurt sauce are rife in Europe as döner kebab and are generally associated with the Middle East, while in Mexico, without the yogurt sauce, they have become assimilated as shepherd’s tacos (tacos al pastor). Kebabs on a skewer and stuffed vegetables both carry the same message, as does Turkish Delight, baklava and the proliferation of the date industry. Couscous has become a staple in France; yogurt, in sweetened form, has become a standard breakfast or snack in Europe and across the Americas.

|

| KEVIN BUBRISKI / SAWDIA; STOCKFOOD / LIP |

| Flavorful global Islamic influences appear also on tables as distant as those in Puebla, Mexico, famous for its mole sauce, left, and others in India—and restaurants worldwide—where chicken curry is one of India's most popular dishes derived from the Mughal-style cuisine that has roots reaching back to Persia and Baghdad. |

In Europe and the Americas, restaurants feature Lebanese, Persian, Mediterranean or “Indian” (where Indian should more properly be understood as referring to the subcontinent rather than the nation) food with dishes from the Islamic tradition. In China, where Muslims, although found in all regions, are clustered in the northwest, migrants to other cities offer street stalls selling noodle dishes. Cookbooks in many languages, often written by migrants, teach readers how to prepare Middle Eastern, Turkish, Persian, Arabian, North African and Mughal cuisines—or at least a version the authors believe will appeal to their audience.

In the 1930s, Maxime Rodinson, Daub Chelebi and A. J. Arberry directed the first serious scholarly attention to medieval Islamic cuisines. Since then, scholars have traced the origins and development of Islamic cuisines, reprinted cookbooks in Arabic, translated them into English and Spanish and offered modern versions of recipes that date back to medieval times. It is thanks to these scholars, and evidence of the public interest that the long history of Islamic cuisines evokes, that it is now possible to write this brief overview of Islamic cuisines and their global role. And to recognize this: that the mint julep of the American south and the gulab jamun of India; the curries of Mughal India and the mole of Mexico; and the glittering aspic of French haute cuisine, the tart cebiche of Peru, and the humble fish and chips of England all share a thousand-year-old taproot.

|

Rachel Laudan (rachel@rachellaudan.com) is a visiting scholar in the Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin and author of Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History (University of California Press, 2013). |