|

|

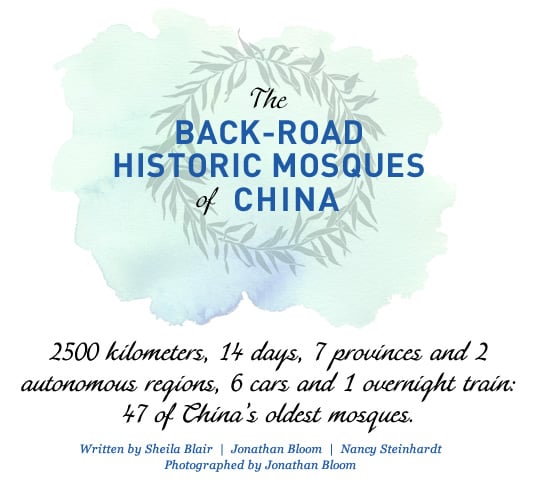

| Paint on wood decorates the entrance to the Great East Mosque at Kaifeng, in Henan province, where Arabic calligraphy appears amid Chinese motifs including dragons, fish, birds, peony and lotus flowers, and symbols for good luck; a string of led lights winds around the rafters that support the tile roof. |

In a country known for large numbers, it was a modest, round number that grabbed our attention: 100. That is the approximate number of mosques built before 1700 that are estimated to remain throughout central and northern China—out of some 30,000 mosques over an area larger than either Texas or France. We set out, traveling highways and back roads, in search of the oldest, least well known among them.

|

| Offering both an entry and a frame for the view beyond it, a circular opening in a wall is known in China as a moon gate. A common feature in gardens, it was also used in religious architecture and, as we see here, in the wall at the Great Mosque of Xian. |

o prepare, we briefed ourselves with more numbers. Of China’s more than 1.3 billion citizens, some 1.8 percent, or 23 million, are Muslims. This Muslim population comprises 10 major ethnic and language groups including 10 million Chinese-speaking Hui and 8.4 million Turkic-speaking Uighurs. The rest are Kazaks, Kyrgyz, Salars, Tatars and Uzbeks, who all speak Turkic languages, as well as Mongolian-speaking Dongxiang and Bao’an, and Farsi-speaking Tajiks.

o prepare, we briefed ourselves with more numbers. Of China’s more than 1.3 billion citizens, some 1.8 percent, or 23 million, are Muslims. This Muslim population comprises 10 major ethnic and language groups including 10 million Chinese-speaking Hui and 8.4 million Turkic-speaking Uighurs. The rest are Kazaks, Kyrgyz, Salars, Tatars and Uzbeks, who all speak Turkic languages, as well as Mongolian-speaking Dongxiang and Bao’an, and Farsi-speaking Tajiks.

We did not want to cover, in the short time available to us, China’s well-known historic mosques. These include Beijing’s Ox Street Mosque, so named for its Muslim neighborhood where oxen—not pigs—were butchered, and the Great Mosque of Xian, both of which are whistle-stops on tourist itineraries. We also avoided tourist favorites in the old port cities along China’s southeastern coast, including the “Cherishing the Sage” Mosque in Guangzhou (formerly Canton); the “Sacred Friendship” Mosque in Quanzhou; the “Phoenix” Mosque in Hangzhou; and the “Transcendent Crane” Mosque in Yangzhou. All of these were bestowed Chinese names that reflected Chinese tenets and myths by their Muslim founders, who arrived in China via the maritime Silk Road. Finally, we excluded a third group of well-known mosques, which serve the Uighur population of Kashgar and other cities of far-western China and whose architecture has much in common with mosques in nearby Uzbekistan and other countries to the west.

|

|

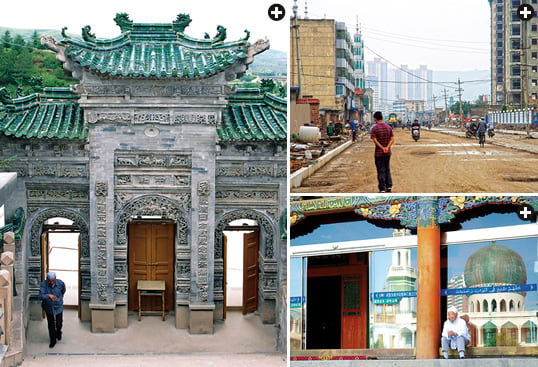

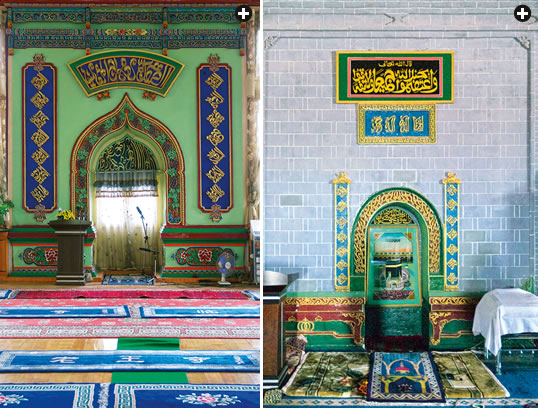

| Top: The first mosque we visited, the Xuanhua North Mosque in northwest Hebei province, shows much that typifies not only the historic mosques we saw, but also other traditional secular and religious complexes in this part of China: A central courtyard surrrounded by low halls and rooms; timber framing; a slightly raised main prayer hall; and perimeter walls of stone or brick. Above: Many historic mosques have undergone renovation in recent years, such as the Beiguan Mosque in Tianshui in Gansu province, where Arabic calligraphy has been left intact above the mihrab or prayer niche, background center. |

Far more intriguing to us were the less-well-known, off-the-beaten-track historic mosques of central and northern China that adopted, adapted and built upon traditional Chinese building designs to meet Islamic needs.

Soon after we met in Beijing, a driver whisked us off for the western Hebei province, northwest of Beijing. Along the three-hour trip, we caught a passing glimpse of the Great Wall before stopping in the city of Zhangjiakou (jang-jea-koo) to visit the Xuanhua (shwen-hwua) North Mosque. There, outside a nearby bookshop, a casual greeting of “as salamu alaykum”—“Peace be with you” in Arabic—was understood with a smile, and it led to an invitation inside: The place was filled with Qur’ans, books and calligraphic inscriptions, in Arabic and Chinese, penned by our host. It was clear this would be a richly fascinating trip.

Indeed, traveling exclusively overland for the next two weeks, we exhausted six different drivers and cars, and rode one overnight train to climb up through the Yellow River Valley from Guyuan to Xining (shee-ning) on the Tibetan Plateau. (See map below) In all, we traversed the seven provinces of Hebei, Shanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Hubei and Henan as well as the two autonomous regions of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia—all areas in central, north and northwestern China with significant Hui populations.

|

|

| The burial sites of men who did much to introduce Islam to central China in the 18th century are marked by pagoda-like structures, such as this one at left, surrounded by buildings for worship and teaching, in Linxia, Gansu province. Little on the exteriors indicates they are historic centers of learning and scholarship. Right: A bas-relief fresco depicts the traditional central Chinese walled building complex. |

Many of China’s mosques are said to have long histories, but it is often difficult to ascertain just how old the edifices are. Nobody likes to talk about what transpired during the Cultural Revolution, which lasted the decade until the 1976 death of Chairman Mao Zedong. During that time, the practice of religion was curtailed, and many religious buildings were appropriated and repurposed. In some places, inscribed stele (upright flat stones), often inscribed in Arabic on one side and Chinese on the other, tell the stories of mosques back through the centuries, but much of what remains dates back no further than the 1700s, and it is often overlaid with modern reconstructions, repairs and repainting, all of greatly varying fidelity to older designs. Indeed, in Tianshui in Gansu province the Beiguan Mosque was in the midst of just such a renovation.

|

| Left: The gateway to the complex at Guyuan in Ningxia Autonomous Region combines typical features of Islamic and Chinese architectural decoration: The exterior ornamentation juxtaposes Arabic and Chinese texts and motifs, incorporating flowers, fruit, birds and real and mythical animals, topped with traditionally Chinese, green-tiled roofs with curling finials shaped as fantastic beasts. Top-right: Minarets of a recently built and stylistically non-Chinese mosque appear down the street, visible at the left, in Linxia, which once thrived on trans-Asian Silk Road trade, and which today hosts the largest number of mosques of any city in China—more than 70, both old and new. Bottom-right: Reflected in plate-glass windows retrofitted onto the porch of the traditional Chinese-style mosque in Xining, capital of Qinghai province and the largest city on the Tibetan Plateau, are the domes and minarets of the nearby, much newer mosque built in "International Islamic” style. |

It was soon after the rise of Islam in the seventh century that Muslims came to China, mainly as ambassadors or merchants. They came both by land, along the Silk Roads through Central Asia, and by sea, over the Indian Ocean via the Straits of Malacca. Historical sources claim that in 651, an envoy representing the third caliph, Uthman, came to the Tang court at Chang’an in central China. With the spread of Islam into Central Asia and the conversion of the Turks to Islam, cities in the western province of Xinjiang (sheen-jee-ahn) became important centers of Muslim culture as early as the 10th century. Apart from some 12th-century tombstones found in coastal cities, however, the first physical evidence for the presence of Muslims in China dates to several 14th-century mosques in the southeast that today are much reconstructed.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, followers of Afak Khoja, who was buried in 1693 or 1694 outside Kashgar in Xinjiang province, brought a wave of Islam east into Gansu, Ningxia and other regions of central China. The disciples’ tombs became the centers of religious complexes that also included rooms for worship and teaching. These buildings adapted traditional Chinese forms and motifs to meet the needs of Islam, but they did so in ways that might surprise visitors from western Islamic lands. For example, many are decorated not only with Arabic calligraphy, but also with traditional Chinese figural and representational scenes. The city of Linxia (lin-shee-a) in Gansu province is home to many such complexes, which serve not only as centers of Muslim scholarship, but as oases of quiet amid urban life.

|

| The gateway to the new Hui Culture Park, bottom-right, stands only a short distance from the Na Family Mosque (left), but is 3000 kilometers (1865 mi) and four centuries from its architectural model, the Taj Mahal, built in Agra, India, by the Mughal emperor Jahangir in the 17th century. This cultural park reflects both new wealth in China and the globalization of Islamic culture. Top-right: The Na Family Mosque at Yongning in the Ningxia Autonomous Region reflects traditional Chinese architecture with its balconies and upturned tile roofs, but the recently restored arched gateway and the two flanking, gray brick towers evoke the later influence of Middle-Eastern mosques with the symmetry of a main entrance flanked by minarets. The mosque's stepped minbar, or pulpit, is another Chinese adaptation of a traditional Islamic form. Behind it, the wall is painted with a medallion similarly combining Chinese motifs and Arabic calligraphy. |

Along with the old, we also discovered much that is new. In earlier centuries, it was particularly arduous for Muslims in China to make the long journeys to centers of Muslim learning to the west, most notably the Hajj, or pilgrimage, to Makkah, which might have taken as long as two years. Today, China’s Muslims, with the rest of the nation, are more connected to the rest of the world than ever, and the architectural consequences of this are increasingly apparent: Many old mosques are now paired with gleaming new ones, often funded from abroad and often designed in what may be called “International Islamic” style marked by pointed green domes and slender, tall minarets—neither of which have any roots in China. We saw one particularly striking example of such indigenous-Chinese and imported design juxtaposition in Yongning in Ningxia, where the traditional Na Family Mosque (also called Naijahu Mosque) stands near the Hui Culture Park, whose designers appear to have been inspired mostly by India’s Taj Mahal.

|

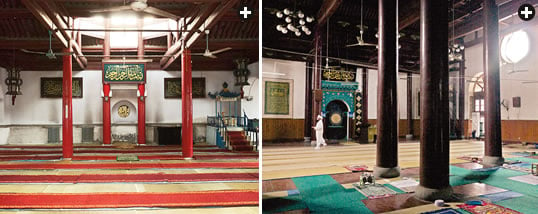

| A rectangular, wooden post-and-beam structure raised on a platform with outer walls of brick and a tile roof, the Zhuxian Mosque in Kaifeng, Henan province, left, differs little from the worship hall at the Buddhist monastery at Ledu, on the Tibetan Plateau near Xining, right. At the mosque, the two small pavilions on either side of the path—which in a Buddhist setting might be drum and bell towers—here contain stelae, or upright stone slabs, chronicling the history of the mosque. |

|

These new mosques using non-Chinese designs are dramatic examples of change within a deeply traditional architectural culture that has applied common design principles consistently to all kinds of secular and religious buildings over several millennia. The palaces of rulers and other elites, which are really just very big houses, served as models first for Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian temples and later for mosques. As a result, a surprising number of Chinese buildings resemble one another closely. For example, a ninth-century Buddhist temple, a 13th-century Daoist temple, a 15th-century mosque, a 16th-century funerary hall, a 17th-century Confucian hall and a 19th-century residence may all exhibit unmistakable similarities. Why Chinese architecture has so many shared features among such varied purposes, across so many geographic and ecological regions, over millennia, was a question that framed our journey from city to city, mosque to mosque. While the size of the buildings and the quality of the materials showed differences in the status and patronage of the structure, they did not often point to any difference in purpose.

One simple answer to the question, which is exemplified by mosque architecture from the 14th to the 20th centuries, is flexibility. They were all built using timber framing braced by sets of wooden brackets; roofed in ceramic tile; grouped in complexes arranged symmetrically along horizontal axes around rectangular courtyards; and set behind walls, usually of brick, with a main gate to the south.

One simple answer to the question, which is exemplified by mosque architecture from the 14th to the 20th centuries, is flexibility. They were all built using timber framing braced by sets of wooden brackets; roofed in ceramic tile; grouped in complexes arranged symmetrically along horizontal axes around rectangular courtyards; and set behind walls, usually of brick, with a main gate to the south.

|

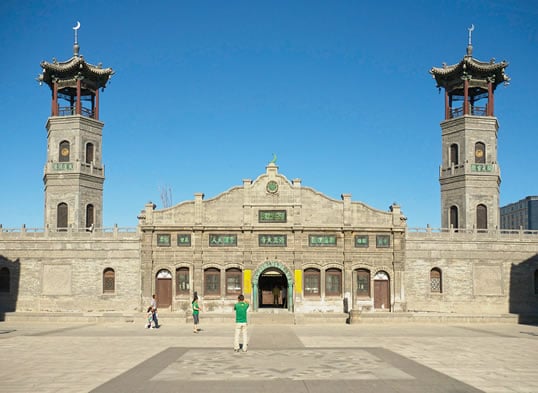

| The two three-story towers flanking the portal to the recently restored 18th-century mosque at Datong in northern Shanxi province are local interpretations of a recently universalized, non-Chinese symbol of Islam. The crescent finials at the top of the towers are complemented by Chinese bells hanging from the eaves. |

Therefore, to turn a traditional Chinese palace or temple plan into a mosque was often as straightforward as orienting the complex to face Makkah, which in China was long understood to be due west. The prayer hall is generally the main building, and it sits in the center of the complex on a platform or plinth as a show of its importance—a practice unique to China. Along the courtyard walls gather auxiliary structures for classrooms, offices and ablutions, as well as residences for the staff, students and travelers—all functions that in some Islamic lands are frequently accommodated in separate or adjacent buildings such as the madrassah (religious school), kuttab (elementary school), khanaqah (hospice), imaret (soup kitchen) and the like. Most of these functions—education, administration, living quarters for religious leaders and visitors—appear no less in Chinese Buddhist and Taoist complexes.

|

| Set within a traditional Chinese frame, Arabic calligraphy, left, is often used to decorate the walls of mosques, as here at the entrance to the Great East Mosque at Kaifeng. The fluid line is typical of Chinese calligraphy, which is normally executed with a brush, rather than the reed pen used elsewhere in Islamic lands. Center: Usually located in the middle of a mosque's courtyard, the pagoda-like wangyuelou, or “moon-watching tower,” is not a minaret, although today loudspeakers mounted on this one at Xunhua in Qinghai province show that it has been adapted to that purpose. Right: The roofs of traditional buildings in China are normally covered with glazed ceramic tiles, some of which are decorated along the ends and ridge lines with vegetal and floral motifs as well as with fantastic beasts, such as dragons and phoenixes. The ends of some of the cylindrical tiles are molded with Arabic inscriptions, while others are stamped with dragons. All of these features combine here on the roof of the Great Northern Mosque in Qinyang, Henan province. |

|

| At a sweet shop outside the mosque at Hohhot, capital of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, the signs are mainly in Chinese characters, but the Arabic in the small oval shows that the food is halal, or permissible for Muslims. However, the Arabic letters in the oval are written incorrectly as separate characters, like Chinese. |

This traditional Chinese architectural system is furthermore generally low in profile, apart from the pagoda, which is the Chinese version of the Indian Buddhist stupa, a symbolic mountain containing Buddhist relics. The minaret, the tower adjacent to a mosque from which the call to prayer is given, was not necessarily part of the traditional Chinese mosque, although in some places Chinese builders transformed the pagoda into the wangyuelou, or “moon-watching tower,” which was located in the middle of the mosque’s courtyard. It was not used for the call to prayer; that function was, and still often is, performed from the doorway of the mosque, now with electronic amplification.

|

| Chinese traditional architecture is generally based on timber posts and beams, and it does not normally use arches. An exception is the long association of the arch with the mihrab, the niche in the Makkah-facing wall of a mosque, which introduced this otherwise novel shape into Chinese mosques. Left to right: Mihrabs in Linxia (Old Wang Mosque), Tongxin and, below left, Dingxiang. Below right: Painted timber beams in Dingxiang. |

|

| Baoding and Kaifeng (Zhuxian Mosque). |

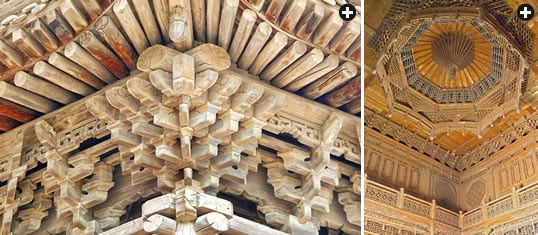

While in most of the dry-climate Muslim world, builders favored brick and stone due to the scarcity of wood, in China timber has always been abundantly available. Traditional Chinese timber-frame construction, whether for palaces, temples or mosques, relied on wooden posts to hold horizontal beams that in turn supported the rafters and roof. These elements were joined using a pegged mortise-and-tenon system with braces, known as bracket sets: No nails, no screws.

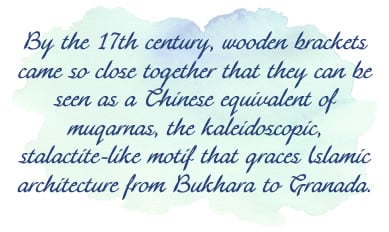

This craftsmanship grew in complexity from the 14th to the 17th centuries. Simple bracket sets with two or three layers of “arms” in 14th-century buildings become bracket sets that clustered in five to seven layers, along nine different angles, by the 17th century. Eventually, the brackets came so close together that it can be seen as a Chinese equivalent of muqarnas, the kaleidoscopic, stalactite-like motif that graces Islamic architecture from Bukhara to Granada.

|

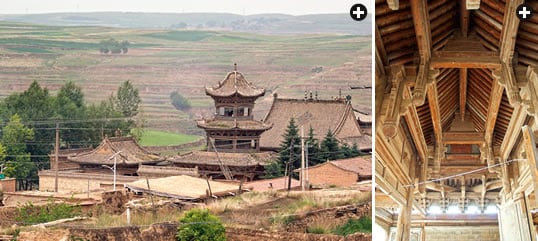

| On the upper reaches of the Yellow River, in Qinghai, the Hongshuiquan mosque is one of the best-preserved, most evocative mosques in central China. Its entrance hall, right, displays an extraordinarily clear example of a traditional Chinese timber-frame construction, in which all the posts, beams and supporting brackets are slotted together with mortise-and-tenon joints that use no metal nails or screws. |

While wood was the most important material for construction, brick was characteristically used for the outer, dividing walls of buildings, and ceramic tile was used for roofing. Although traditional Chinese builders did know and use both arches and vaults, they did so mostly for underground tombs, not for aboveground architecture.

For Muslims, however, the arch has a particularly religious significance: Since its introduction in early Islamic times, the mihrab, or niche in the Makkah-facing wall of a mosque (qibla), has invariably taken an arched form that appears, with variations, to this day. Again owing to the dearth of timber in North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia, the common technique for covering a space became the vault of brick or stone—vaults being no more than arches rotated and, for length, extended in space. Chinese Muslims, too, seem to have at times associated vaults with Islam, since some of the timber-frame mosques we saw showed arched and vaulted spaces made of brick in the most important part of the building: the bays in front of the mihrab. This kind of construction is known in Chinese as a “beamless hall.” And at other times, the wood construction actually imitated a domed space without relinquishing its structural reliance on posts and beams.

|

| Because Chinese architecture has been so consistent over millennia, one way of dating a building is to look at the complexity of the “bracket sets,” the wooden braces that support the roof: The more complicated the bracket sets, the later the building. These at the Hongshuiquan mosque point toward the 18th or 19th centuries. Right: At the Hongshuiquan mosque, the mihrab stands in this small square room covered by exquisite carved paneling and this elaborate wooden ceiling that evokes a dome. |

The decoration of the mosques we saw similarly combined traditional Islamic motifs of calligraphy, and geometric and vegetal ornament with traditional Chinese ones of peonies, lotus flowers, dragons and phoenixes. The use of Arabic script is the most obvious difference between Muslims and others in China, whether in the mosque or in the marketplace.

Arabic calligraphy in China often displays an exceptionally fluid line that reflects the long Chinese tradition of writing with brushes rather than the reed pens of other Islamic lands. In the case of vegetal and floral ornament, there is much overlap between the two traditions, but it is uniquely Chinese to depict mythical beasts in Islamic religious settings, where figural representation is normally avoided. Sometimes these beasts are set like guardian figures flanking doorways or decorating roofs; at other times they integrate into the carved and painted decoration. In a similar way, in some mosques Muslims adopted the traditional Chinese use of incense, and in some courtyards one can find large bronze or ceramic vessels, inscribed in Arabic and Chinese, filled with sand that holds smoldering sticks of incense.

Arabic calligraphy in China often displays an exceptionally fluid line that reflects the long Chinese tradition of writing with brushes rather than the reed pens of other Islamic lands. In the case of vegetal and floral ornament, there is much overlap between the two traditions, but it is uniquely Chinese to depict mythical beasts in Islamic religious settings, where figural representation is normally avoided. Sometimes these beasts are set like guardian figures flanking doorways or decorating roofs; at other times they integrate into the carved and painted decoration. In a similar way, in some mosques Muslims adopted the traditional Chinese use of incense, and in some courtyards one can find large bronze or ceramic vessels, inscribed in Arabic and Chinese, filled with sand that holds smoldering sticks of incense.

Perhaps the greatest surprise of our trip was the charming Hongshuiquan (hung-shwee-chew-ahn) or “Vast Spring” mosque at Ping’an, which we reached after several hours’ drive from the city of Xining, high on the loess plateau in Qinghai province, along the upper reaches of the Yellow River. We didn’t quite know what to expect as we wended our way through small agricultural villages built atop millennia of loess deposited by the winds off the deserts of Central Asia.

|

| The custodian of the Hongshuiquan mosque welcomed us. The unusual absence of paint emphasizes the purity of its preservation. |

To our surprise, this remote mosque showed little evidence of restoration, yet its condition was good. As we closed our eyes and listened to a cuckoo serenade us in the stillness so rare in modern China, we were transported back into the 18th or 19th century, when this exquisitely elaborate wooden mosque was constructed.

|

Sheila Blair (sheila.blair@bc.edu) and Jonathan Bloom (jonathan.bloom@bc.edu) share the Norma Jean Calderwood University Professorship of Islamic and Asian Art at Boston College and the Hamad bin Khalifa Endowed Chair of Islamic Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. |

|

Nancy Steinhardt (nssteinh@sas.upenn.edu) serves as department chair and professor of East Asian art at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of China’s Early Mosques, forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. |