|

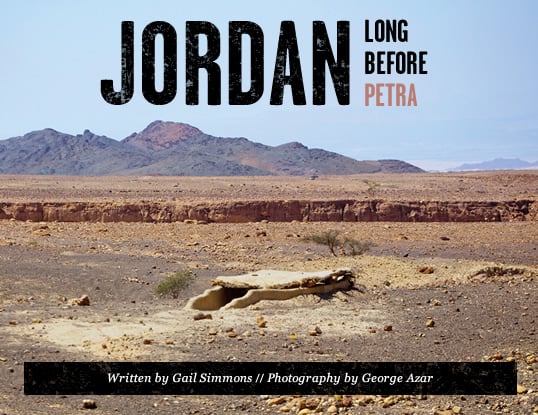

| Looking out over the nearly 12,000-year-old Neolithic site in southern Jordan called WF16, it is hard to imagine that the people who lived here—some in partly subterranean huts like this reconstructed one—were likely on the cutting edge of an agricultural revolution. |

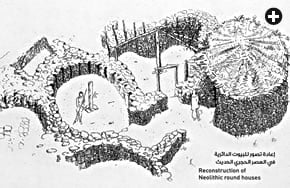

It is late afternoon in Wadi Faynan, an arid, tributary valley that opens into Wadi Araba, the long, broad segment of the Great Rift Valley that links the Dead Sea to the north with the Gulf of Aqaba to the south. I’m crouching inside an oval-shaped, mostly underground hut. It’s a cozy place, one that would provide some shelter from rain, sun and cold—though add a few more people, and it would quickly feel cramped. It is roofed with mud-covered branches. Through window-like openings near the low ceiling, I can see the sun begin its descent behind the serrated silhouette of the surrounding Sharah Mountains as it rakes the sky with rose and apricot.

utside I hear only wind and birdsong, but in my imagination I can travel back nearly 12,000 years to when this was a small but thriving community, occupied most likely for only parts of each year. Then, there would have been voices, people calling out to each other, the patter of children running about; perhaps the rasp of flint against bone as animal carcasses were cleaned; and—most significantly to archeologists today—the thumps and scrapes of pestles against mortars as cereals were ground into a rough flour.

utside I hear only wind and birdsong, but in my imagination I can travel back nearly 12,000 years to when this was a small but thriving community, occupied most likely for only parts of each year. Then, there would have been voices, people calling out to each other, the patter of children running about; perhaps the rasp of flint against bone as animal carcasses were cleaned; and—most significantly to archeologists today—the thumps and scrapes of pestles against mortars as cereals were ground into a rough flour.

It’s not only my imagination that has conjured this scene. On this spot, one of just a few identified to date in southwestern Asia, archeologists have evidence of what were likely some of the first experiments in communal living and farming. Here, discoveries of plant remains indicate that Neolithic (“New Stone Age”) people gathered and processed wild barley, and then they possibly began sowing, nurturing and harvesting it, a practice that in time domesticated the plant and transformed history.

The landscape near my shelter is littered with fragments of knapped flint—remnants of the former inhabitants’ hand tools—as well as lumps of hollowed-out stone that were used to laboriously pulverize grain by the handful. A few meters away are the telltale bumps and contours of at least 30 round structures that may have been storage buildings, with floors aboveground and with multiple chambers, some like the one I am sitting in now.

|

| Excavated remains of stone-wall structures dating to 8500-6250 bce—before the development of pottery—lie along Wadi Ghuwayr, uphill about 15 minutes’ walk from the older site of WF16. These show evolution in architecture from WF16’s mud walls, and here archeologists have also uncovered evidence of the cultivation of cereals. |

Although radiocarbon dating of charcoal deposits suggest that this place was inhabited first more than 100 centuries ago, my hut is a replica, constructed a few years back on the one-hectare (2-ac) site that archeologists have been excavating on and off for nearly 20 years.

It’s beginning to grow dark outside. Mohammed Defallah, a local Bedouin goat herder turned travel guide, calls. I emerge from the shelter and my reverie. He’s brought me here from nearby Faynan village. Earlier, he’d also baked some bread for lunch here, mixing a ball of flour with water, then kneading the lump of dough and forming it into a perfect flatbread on an ancient mortar stone he found nearby. Sweeping aside the embers of an acacia-wood fire, he placed the dough under the fire-hot sand, and minutes later it was some of the freshest bread I’d ever tasted. It struck me that I had just witnessed a scene that may have been little changed since bread was first baked here thousands of years ago.

his site at Faynan is just one of the dozens of Neolithic settlements discovered in the southern Levant, but it is proving one of the most significant. Faynan shows evidence that the great shift from hunting and gathering to crop-raising—the “agricultural revolution”—took place not only widely across the region, but also much farther south than previously believed, and it offers clues to how that change took place.

his site at Faynan is just one of the dozens of Neolithic settlements discovered in the southern Levant, but it is proving one of the most significant. Faynan shows evidence that the great shift from hunting and gathering to crop-raising—the “agricultural revolution”—took place not only widely across the region, but also much farther south than previously believed, and it offers clues to how that change took place.

Dating to between 10,000 and 8500 bce, Faynan is one of the earliest of the Neolithic sites discovered in the entire Middle East, which in turn means “it’s one of the earliest in the whole world,” says Steven Mithen, an archeologist from University of Reading, uk. An expert in the origins and spread of farming, Mithen first visited Faynan in 1996, and he has been working here since 1997 alongside both Bill Finlayson, regional director of the London-based Council for British Research in the Levant (cbrl), and Mohammed Najjar, former director of excavations at Jordan’s Department of Antiquities. “It’s an especially well-preserved site, probably used by people who were just experimenting with the cultivating of plants,” Mithen says.

|

| bill finlayson / wadi faynan project |

| In 2010, the team working at WF16 unearthed remains of what is now Wadi Faynan’s most astonishing discovery: an amphitheater-like building that dates to 9700 bce, prior to known agriculture. It calls into question the assumption that agriculture brought on higher social organization: Was it the other way around? The structure has been covered over to protect it against weathering until it can be studied further. |

Beyond this, one particular discovery makes Faynan even more significant: In 2010, the archeological team, which included university students and local Bedouin, unearthed—to their astonishment—an amphitheater-like structure measuring 22 by 19 meters (70 x 61'), or roughly the size of two tennis courts. It dates to about 9700 bce—before any known agriculture. It is the largest known building of its era.

A meter-wide bench runs around about half its circumference, decorated with a wave pattern like that found on stone artifacts from the site and partly backed by another tier of seats. A 1.2-meter-deep (4') channel runs its length, flanked at one end by two stone platforms containing cup-shaped mortars. Close by, archeologists uncovered broken pieces of stone bowls. There are also postholes in the floor that they say are likely to have held wooden pillars.

“Whether [the structure] was used for a functional activity like grinding grain, or some ceremonial purpose such as feasting or sacrifice, we don’t yet understand,” says Mithen. “But what is really striking is its age, representing the very earliest period of the Neolithic.” Although now backfilled for protection from the elements, the building is still discernible from the depressions just beneath the surface of the ground where I stand.

|

| This artist’s depiction of the round, stone houses at Wadi Faynan in its Neolithic heyday appears on a sign at the site. |

“When we first came here hoping to find a prehistoric site, ideally of the Neolithic period, other archeologists told us there was no chance,” Mithen recalls. “They said this region of the Levant, at the very southern tip of the Fertile Crescent, was a backwater. They argued that it was all happening in the Mediterranean lands in the other side of the Jordan Valley near Jericho, or hundreds of kilometers north in Turkey where Göbeklı Tepe had just been discovered.”

Jericho and Göbeklı Tepe are two of the most important previously known early Neolithic sites in the wider region. Jericho, 125 kilometers (75 mi) north of Faynan in the West Bank, was excavated first in the 1950s by British archeologist Kathleen Kenyon. Discoveries there include an 8.5-meter (28') tower, a massive stone wall and a number of round structures similar to those now known at Wadi Faynan. Göbeklı Tepe, in southeastern Turkey, is unique for its elaborately decorated, rectangular stone pillars—some standing three meters (10') tall—excavated beginning in the 1990s by the late German archeologist Klaus Schmidt.

“What we see now is that in the Levant, human development was not happening in just one place,” says Mithen. “There were contemporary developments in many different areas.”

|

| Pink oleanders track the trickle of water in Wadi Faynan, which today runs much drier than in Neolithic and earlier times. Indeed, discoveries in the vicinity trace human history back a million years, almost without a break. |

he early Neolithic site at Wadi Faynan now carries the prosaic name WF16, which distinguishes it by number from other nearby sites that together, along this mostly desiccated watercourse, comprise a million years of human records. It starts with the discovery of Lower Paleolithic (“early Old Stone Age”) hand axes, and it shows a nearly continuous progression to the present.

he early Neolithic site at Wadi Faynan now carries the prosaic name WF16, which distinguishes it by number from other nearby sites that together, along this mostly desiccated watercourse, comprise a million years of human records. It starts with the discovery of Lower Paleolithic (“early Old Stone Age”) hand axes, and it shows a nearly continuous progression to the present.

Half a kilometer east (1/3 mi) of WF16, at the entrance to Wadi Ghuwayr, is a site dating to 8500-6250 bce, a later Neolithic period, before the development of pottery. Five kilometers (3 mi) down Wadi Faynan, a large tell, or mounded former habitation site, shows signs both of farming and of copper mining and smelting. It dates to 5500 years ago—around the beginning of the Bronze Age.

And then there are Roman, Byzantine and Islamic sites: Faynan was the greatest copper mine in the Roman Empire, and later, during the Byzantine era, it was known as Phaenon, home to the bishopric of Palaestina Tertia. Islamic ruins include a Mamluk-era caravanserai. This immense timescale prompts archeologists working at Wadi Faynan to contend that few, if any, places in the world can claim such a long record of continuous human activity.

|

| A desert lark sits atop a stone at Wadi Faynan, where communal life may have set in motion the first steps toward the domestication of wild plants—and civilization as we know it. |

But it is WF16, with its mysteriously ancient amphitheater and the questions it raises about the story of mankind’s development, that excites Neolithic experts like Mithen. “It may not look as spectacular as Göbeklı Tepe,” he tells me, explaining that the postholes at WF16 “may well have held [wooden] totem poles which haven’t survived,” or maybe they held up a roof. “If there was ever a roof over that structure, it would have been a very spectacular one,” he says.

Whatever the purpose of the building, it was apparently a focal point for the community. Archeologists still don’t yet know how sedentary the people who gathered here actually were: They may have assembled only at certain times of the year, perhaps to process or celebrate the harvest of wild plants. And because the structure predates farming, which began around 8000 bce, some 10,000 years ago, it raises a compelling question of human social development: Did gathering for communal activity help people launch agriculture? To date, archeology generally has assumed that it worked the other way around: The rise of agriculture facilitated communal, sedentary living. But now, maybe not.

|

| Before the discovery of WF16 in the mid-1990s, Beidha was the best-known Neolithic site in Jordan. It lies on the route of the Neolithic Heritage Trail, south of Wadi Faynan and just a few kilometers north of world-renowned Petra, the monumental Nabataean trading city built around the beginning of the fourth century bce. |

The hypothesis that WF16 was a seasonal rather than a permanent meeting place has the support of Gary Rollefson, an archeologist from Whitman College in Washington state who has worked on Neolithic projects in Jordan’s Eastern Desert for many years. WF16 appears to be a place “for temporary social activities centered around possible harvest and hunting,” he says. Marriages, gift exchanges and communal work at those same times would have fostered “social identity and solidarity,” he adds. This could have been helpful in organizing early plantings and harvests.

Similar questions of purpose have arisen from Göbeklı Tepe, although no apparent storage or workshop structures have been located there. “Göbeklı Tepe is not as representative of the ‘normal’ Neolithic world as somewhere like Faynan,” Mithen says, adding that, in addition, Faynan’s architectural remains are more precisely dated and better preserved than those at Jericho.

WF16 is also currently among the region’s most accessible Neolithic sites. Jerf el-Ahmar, in northern Syria, disappeared in 1999 under waters retained by the Tishrin Dam, says Finlayson, who discovered WF16 and has spent many seasons working in southern Jordan. He notes that political upheaval has curtailed access in northern Iraq, and that sites in Iran excavated in the 1950s and ’60s have been hard to reach since the 1979 revolution.

Here in Wadi Faynan, the climate, too, favored its preservation. Situated at the southern tip of the area in which cereals could grow wild, it was always a marginal place subject to less intensive agricultural and urban development than the better-watered areas to the north and west—activities that tend to degrade and erase delicate Neolithic remains.

tanding on a mound at WF16 today, it’s hard to see how this waterless, rock-strewn terrain could have supported an otherwise unassuming community that happened to be on the cutting edge of an agricultural revolution. But then, the climate was wetter, and both hunter-gatherers and early farmers would have been within easy reach of the nearby upland plateau rich with woodlands of oak, fig and pistachio. Today, only a few patches of evergreen oak forest remain there, along with some protected woodland at the southern end of the Dead Sea, to hint at the far more verdant, Neolithic world.

tanding on a mound at WF16 today, it’s hard to see how this waterless, rock-strewn terrain could have supported an otherwise unassuming community that happened to be on the cutting edge of an agricultural revolution. But then, the climate was wetter, and both hunter-gatherers and early farmers would have been within easy reach of the nearby upland plateau rich with woodlands of oak, fig and pistachio. Today, only a few patches of evergreen oak forest remain there, along with some protected woodland at the southern end of the Dead Sea, to hint at the far more verdant, Neolithic world.

|

| For nearly a million years until relatively recent times, Wadi Faynan and environs were attractive places for making a living and trading. With several Neolithic sites, its importance as a commercial thoroughfare is shown by finds of seashells from the Mediterranean and the Red seas as well as bitumen, used to cover baskets, from the Dead Sea to the north. |

Mithen hopes that new work at WF16, scheduled for 2017, may reveal evidence of “when it actually started, and whether we see a long-term transition from very mobile hunter-gatherers to more sedentary hunter-gatherers to completely sedentary farmers.”

What the archeologists do know is that WF16 was abandoned around 10,500 years ago. Its most likely successor site is the nearby, 1.2-hectare (3 ac) area on a steep hillside at the entrance to Wadi Ghuwayr, which was excavated in the 1980s. Its small, rectangular buildings, with interior plastered walls and adjacent passageways, date to the period when villages were known to be forming, and farming was well under way.

What impresses a visitor to Ghuwayr is the sense of shared purpose, visible even in the ruins, represented by the walls, stairs and windows visible in these more complex buildings. People were making big advances living together, forming long-lasting communities and organizing large-scale cooperative projects here, the archeologists explain. And they were probably cooperating not only internally, but also with others throughout this region and the wider Levant, in areas such as Jericho.

From Ghuwayr, I can see far down Wadi Faynan to the flat haze of Wadi Araba, which served as an obstacle-free, north-south thoroughfare enabling hardy people to share trade, technologies, ideas and discoveries. Finds at Wadi Faynan include seashells from the Mediterranean and Red Sea coasts (some made into beads) and raw materials such as bitumen from the Dead Sea (probably used to cover baskets). These and other finds help archeologists believe that there is now enough evidence to begin to piece together patterns of the region’s earliest commerce.

“There’s obviously contact—though not necessarily everyday contact,” says Finlayson. “We now realize this was a massively networked world, with no one place acting as the ‘origin point’ of agriculture. It’s as if people were all exploring the same idea, but expressing it differently.”

Or, as Rollefson puts it, “religion, ritual, and social interaction were not genetically programmed in these populations; instead, such activities were very different, locally developed variable solutions to problems that affected all human societies in that revolutionary period.”

In addition to Wadi Araba, there was also Wadi Namla, which links Faynan to the world-famous site of Petra, 50 kilometers (30 mi) to the south. That famous trading city was established by the Nabataeans around the fourth century bce, but millennia before Petra there was a road linking Neolithic sites along it, including Shkarat Msaied, Ba’ja and Beidha, excavated in the 1950s and, until Faynan, the most prominent Neolithic site in southern Jordan.

am heading to Beidha now, along the Wadi Namla road, which winds through the granite and sandstone of the Sharah Mountains. As it descends toward Beidha, the rugged scenery gives way to valleys planted with barley, temporarily lush after spring rains. Unlike at parched Faynan, here it’s not hard to imagine the region as it may have been in the Neolithic period.

am heading to Beidha now, along the Wadi Namla road, which winds through the granite and sandstone of the Sharah Mountains. As it descends toward Beidha, the rugged scenery gives way to valleys planted with barley, temporarily lush after spring rains. Unlike at parched Faynan, here it’s not hard to imagine the region as it may have been in the Neolithic period.

What’s visible of Beidha dates mostly from the later pre-pottery Neolithic, after Faynan. I rendezvous with Finlayson and his colleagues Mohammed Najjar and Cheryl Makarewicz, an archeologist from Kiel University in Germany. Finlayson, who arrived at Beidha in 2000 and has been digging here intermittently ever since, shows me around its complex of circular and rectangular houses. Two buildings have been reconstructed nearby, partly so archeologists can test hypotheses about building techniques, and partly to give curious visitors from Petra, just a few kilometers to the south, something to see, much as with the reconstruction at WF16.

|

| Posing amid the dig site in Beidha, from left, are archeologists Mohammed Najjar, former director of excavations at Jordan’s Department of Antiquities, Cheryl Makarewicz of Kiel University in Germany, and Bill Finlayson, regional director of the Council for British Research in the Levant. |

Unlike Wadi Faynan, where there is evidence stretching almost seamlessly back to the early Neolithic and before, here the archeological record shows that the immediate area lay abandoned from around 6500 bce until the early Nabataean period some 6000 years later.

“There’s something that happens at the end of this early Neolithic period when people begin to gather together in a large scale,” says Finlayson. “Beidha may have been too small to be part of that process, and may have been absorbed into a much bigger community. Or maybe they just exhausted the soil, or the local springs dried up.”

Beidha and its great Nabataean neighbor Petra flourished in a far more water-rich environment than today. Indeed, much of what’s known about Petra’s extensive and sophisticated water-management system probably applied to Beidha. But Finlayson is wary of too many analogies to Petra.

|

| Ba’ja, the second-to-last stop on the 50-kilometer (31 mi) Neolithic Heritage Trail, under development and linking Wadi Faynan to Beidha, is reached through the spectacular, rock-strewn obstacle course called Siq’ al-Ba’ja. While drivers can traverse the trail in a single day, hikers can savor it over four or five days with a local guide. |

“Beidha is definitely not a ‘pre-Petra,’” he says. “The problem is, every site around Petra tends to be seen through a Nabataean lens.”

Now, as Finlayson resumes his work on the excavation beneath the unrelenting sun, I cast my mind back to Faynan, pondering how long it might be until people begin to see the rest of southern Jordan through a Neolithic lens, too.

|

Historian and travel writer Gail Simmons (www.travelscribe.co.uk) surveyed historic buildings and led hikes in Italy and the Middle East before becoming a full-time travel writer for uk and international publications. She holds a master’s degree in medieval history from the University of York and is currently earning her Ph.D. She lives in Oxford, England. |

|

Photojournalist and filmmaker George Azar (george_azar@me.com) is co-author of Palestine: A Guide (Interlink, 2005), author of Palestine: A Photographic Journey (University of California, 1991) and director of the film Gaza Fixer (2007). He lives in Jordan. |