hen Tamerlane fell ill in 1404, his armies had already destroyed cities from Moscow to Delhi, as well as the principal centers of the Islamic heartlands. The Ottoman sultan Bayazid had been defeated; Mamluk Egypt had been granted a humiliating peace. Only China remained to be conquered.

hen Tamerlane fell ill in 1404, his armies had already destroyed cities from Moscow to Delhi, as well as the principal centers of the Islamic heartlands. The Ottoman sultan Bayazid had been defeated; Mamluk Egypt had been granted a humiliating peace. Only China remained to be conquered.

|

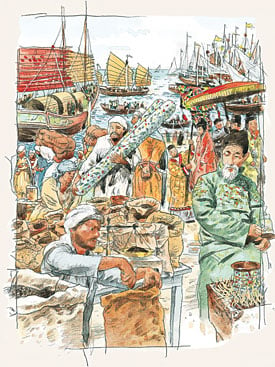

| A modern illustration shows Zheng He and one of the giant, nine-masted “treasure ships” in which he made seven voyages around the Indian Ocean, traveling as far west as Jiddah, trading and collecting tribute. Had the voyages not been abruptly curtailed by a change of government policy, Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean might have countered that of Portugal. YU ZHENG / CHINA STOCK |

But Tamerlane died in January 1405, on the eve of his long-planned invasion of China. The destruction of so many cities on the overland East–West trade routes —especially Isfahan, Baghdad, Damascus, Aleppo and Smyrna—and the slaughter of their populations had been a terrible blow to the Asian economy. The political instability following Tamerlane’s death made the search for a sea route to India imperative, both for Europeans and for the Chinese.

As Tamerlane lay dying, the Yongle emperor of the Ming was already assembling an Indian Ocean fleet so large it would not be surpassed until World War II. And in 1405 the first of what would become seven major Chinese naval expeditions set sail to explore the Indian Ocean.

The admiral of all seven fleets was Zheng He, the great-grandson of a Mongol warrior. His original name was Ma Ho, the Chinese version of Muhammad, for his father was a Muslim who had made the pilgrimage to Makkah. In 1404, the emperor conferred on him the honorific Zheng, and he was appointed Grand Eunuch, thenceforth to be known as Zheng He.

The figures given for the size of Zheng He’s first fleet seem incredible, but there is no doubting them. There were 317 ships of different sizes, 62 of them “treasure ships” loaded with silks, porcelains and other precious things as gifts for rulers and to trade for the exotic products of the Indian Ocean. The ships were manned by a total of 27,870 men, including soldiers, merchants, civilians and clerks—equivalent to the population of a large town.

Perhaps most astonishing are the dimensions given in later Chinese sources for the treasure ships: They were said to be some 140 meters (450') long by 57 meters (185') wide, carrying nine masts. This is twice the length of the first transatlantic steamer, which then lay four centuries in the future! Admitting the impossibility of these dimensions, it still seems certain that these were very big ships. Marco Polo voyaged to India in 1292 in a junk with a crew of 300, and Nicolò dei Conti mentions five-masted junks of perhaps 2000 tons.

The bow and stern of these junks were almost square and heavily reinforced, as was the hull, which had bulkheads that formed self-contained, watertight holds. The largest ships had as many as 50 cabins. The sails were made of bamboo matting, slung fore and aft. The mainsail was raised with a windlass; on the larger junks, it weighed five tons. They ships were slow-moving, making about four and a half knots, but they could sail close to the wind. They were perfectly suited to deep-sea sailing; however, as Ibn Battuta’s disaster in Calicut showed, they were vulnerable in shallow water.

Each ship had an official whose job it was to take compass readings. It is hard to know how accurate these could have been, though Chinese navigators, like the Arabs, corrected their compass readings by celestial observation, using the cross-staff or the kamal. They found their latitude from the stars and had stellar charts to help them do so. Speed was measured by dropping a floating object over the side and timing its passage along the length of the ship. Watches were timed by burning an incense stick of standard length. Charts were used, but surviving examples are schematic representations of coastal features as seen from offshore, located by elevation of the Pole Star, rather than marine charts with compass bearings like European portulans.

|

| In 1432, Zheng He detached two ships to Aden, but political tensions in Yemen forced them north to Jiddah, where they offloaded silk, porcelain, musk and other goods. NORMAN MACDONALD |

Zeng He’s first argosy called at Java, Sumatra, Aceh, Sri Lanka, Calicut, Champa, Malacca, Quilon and other ports. It brought so many goods to Indian ports that pricing them took three months. His second expedition, said to have set off in 1407 and returned in 1409, consisted of 249 ships; it visited Thailand, Java, Aru, Aceh, Coimbatore, Kayal, Cochin and Calicut, where it spent four months. The third expedition sailed in 1409 and returned in 1411, and although it was composed of only 48 ships, it allegedly carried 30,000 troops, stopping at Champa, Java, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Quilon, Cochin and Calicut.

These first expeditions were motivated above all by the desire of the Ming to display their power and gain token allegiance from the rulers of Indian Ocean emporia. If this submission was not forthcoming, Zheng He did not hesitate to intervene militarily: The ruler of Sri Lanka refused to recognize the emperor and was taken to China as a prisoner. The same fate befell two rulers in Sumatra. Some 37 countries and principalities sent representatives to China to make formal obeisance.

Zheng He’s latter four expeditions were recorded by a Muslim Chinese named Ma Huan, who was attached as a translator to the fourth armada, which sailed in 1413 with 63 ships and 28,560 men. Born near Hangzhou, he had learned Arabic and perhaps Persian, probably from Muslim merchants.

This was the first of the seven expeditions to go west of India, and its objective was Hormuz. Ma Huan’s notes on the ports visited on this and the three later expeditions were published in 1433, the year the final fleet returned, under the title The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shore (Ying-yai Sheng-tan). He wrote, “I collected notes about the appearance of the people in each country, the variations of the local customs, the differences in the natural products and the boundary limits.” In the Chinese court, the expense of these extraordinary expeditions proved controversial, especially at a time when the Chinese army was in disarray following its defeat in Vietnam. Six years passed between the sixth and the final seventh expedition.

Ma Huan’s survey is systematic. It contains 20 chapters of varying lengths, each dedicated to a specific place, beginning in the east with Champa in Vietnam and ending in the west with “The Country of the Heavenly Square”—Makkah. The principal entries are on Champa, Palembang, Thailand, Malacca, Sri Lanka, Quilon, Cochin, Calicut, Dhufar, Aden, Hormuz, Makkah, Sumatra, Bengal, the Maldives and Laccadives, Mogadishu, Brava and Malindi. Each entry gives the essentials, in extremely concise form, of the political, military, religious and economic background of each port. Ethnographic information is included, particularly observations on dress and food and exhaustive lists of the trade goods available. Unfortunately, Ma Huan typically did not distinguish between the products of a particular country and the goods it merely transshipped. Giraffes, he noted, were available in Aden: Though the Chinese bought one as a gift for the emperor, it was of course not indigenous.

Ma Huan’s survey is systematic. It contains 20 chapters of varying lengths, each dedicated to a specific place, beginning in the east with Champa in Vietnam and ending in the west with “The Country of the Heavenly Square”—Makkah. The principal entries are on Champa, Palembang, Thailand, Malacca, Sri Lanka, Quilon, Cochin, Calicut, Dhufar, Aden, Hormuz, Makkah, Sumatra, Bengal, the Maldives and Laccadives, Mogadishu, Brava and Malindi. Each entry gives the essentials, in extremely concise form, of the political, military, religious and economic background of each port. Ethnographic information is included, particularly observations on dress and food and exhaustive lists of the trade goods available. Unfortunately, Ma Huan typically did not distinguish between the products of a particular country and the goods it merely transshipped. Giraffes, he noted, were available in Aden: Though the Chinese bought one as a gift for the emperor, it was of course not indigenous.

Though Ma Huan’s little book has some curious mistakes and omissions, these are minor compared with the wealth of other detail. As a visitor from a different civilization, he noticed things unremarkable to more local visitors. For example, he compares the women’s clothing to that of the Chinese goddess of mercy, Kuan Yin: “Over the body they put on a long garment; round the shoulders and neck they set a fringe of gemstones and pearls…. In the ears they wear four pairs of gold rings inlaid with gems; on the arms they bind armlets and bracelets of gold and jewels; on the toes they also wear toe-rings; moreover, they cover the top of the head with an embroidered kerchief of silk.” This sort of information is all the more valuable because of the general lack of iconographic evidence in the Arab world until the 16th century, when the first illustrated European travel accounts began to be published.

|

| Forty maps illustrating Zheng He’s voyages were preserved by the 16th-century scholar Mao K’un and first published in 1628. The top map shows the stars to steer by between Rajasthan and Hormuz; center and lower segments show the coast of Persia and, in the foreground across the Gulf, Arabia. HSIANG TA, CHENG HO HANG-HAI T’U, BEIJING, 1961 (3) |

In Yemen, Ma Huan seems to have been shown one of manuals on agriculture and agricultural calendars that were compiled under the Rasulid sultans, who encouraged agriculture and the introduction of new crops and techniques. “They will fix a certain day as the beginning of spring,” wrote Ma Huan, “and the flowers will in truth bloom after that day; they will fix a certain day as the commencement of autumn, and the leaves of the trees will in truth fall; so too as regards eclipses of the sun and moon, the varying times of the spring tides, wind and rain, cold and warmth.”

Like Ibn Battuta, Ma Huan carefully listed the foodstuffs available in the markets: “Husked and unhusked rice, beans, cereals, barley, wheat, sesame and all kinds of vegetables…. For fruits they have…Persian dates, pinenuts, almonds, dried grapes, walnuts, apples, pomegranates, peaches and apricots.” Of pastry, absent in Chinese cuisine, Ma Huan could only say that “many of the people make up a mixture of milk, cream, butter, sugar and honey to eat.”

He was impressed by the quality of craftsmanship in Aden. This is remarkable, because it was a commonplace of Arab accounts of China that it was Chinese craftsmanship that exceeded that of all other peoples. “All the people in the country who make and inlay fine gold and silver ornaments and other such articles as their occupation produce the most refined and ingenious things, which certainly surpass anything in the world.” He mentions the markets, the bath houses, the shops selling cooked food and even the bookshops.

When the time came for the Chinese ships to depart, the ruler of Yemen, al-Malik al-Zahir, gave Zheng He gifts for the emperor, among them two gold belts inlaid with jewels, a letter written on gold leaf and a number of exotic African animals. The animals were a tremendous hit in the Ming court, and paintings of zebras and giraffes by court artists have survived. As usual, the Chinese interpreted these gifts as tribute; indeed, they carefully noted every place from which they received goods as a tributary nation to China. We know from Yemeni chronicles that the locals regarded this with great amusement: “The Chinese seem to think everyone is their subject,” said one Yemeni writer, “showing complete ignorance of political reality.”

Zheng He visited Hormuz again on his seventh and final expedition, which lasted from 1431 to 1433. This time the fleet consisted of 100 ships and 27,500 men. He arrived when Hormuz was at the peak of its prosperity. “The king of the country,” says Ma Huan, “and the people…all profess the Muslim religion; they are reverent, meticulous and sincere believers; every day they pray five times; they bathe and practice abstinence. The customs are pure and honest. There are no poor families; if a family meets with misfortune resulting in poverty, everyone gives them clothes and food and capital and relieves their distress…. The limbs and faces of the people are refined and fair; they are stalwart and fine-looking.”

Hormuz was linked by overland routes to the major cities of Iran, Central Asia and Iraq. “Foreign ships from every place,” says Ma Huan, “and foreign merchants traveling by land all come to this country to attend the market and trade; hence the people of the country are all rich.” He describes the local marriage customs, funerary practices and diet.

This same expedition detached two junks to revisit Aden, but when they arrived in 1432, the political situation was tense in Yemen, and the captains of the junks, through a lengthy bureaucratic process, secured permission from the Mamluk sultan to offload their cargo of chinaware, silk, musk and other goods farther north, in Jiddah. Ma Huan disembarked there, at the city he called Chih-ta, and made his way inland to Makkah. He described the Ka‘bah and the rites of the pilgrimage. He apparently had a painter do a painting of the Ka‘bah, which on his return was presented to the emperor.

|

| This Chinese plan of Makkah dates from the early 19th century, and it was probably produced for the use of Chinese pilgrims. With buildings carefully drawn and major sites labeled in both Chinese and Arabic, it is a valuable rendering of the pre modern city. ISAAC, THE ARABIAN PROPHET…, SHANGHAI, 1921 |

The Ming expeditions overawed many local rulers and established a long-lasting relationship between China and the key port of Malacca. They might well have led to a permanent Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean. Yet when the Hung-hsi emperor came to the throne in 1433, he put an end to the official voyages: Senior mandarins were complaining about the expense, pointing out that profits to the state were almost nonexistent, and that the money could be better spent patrolling eastern coastal waters against the menace of Japanese pirates. A Chinese state monopoly of Indian Ocean trade thus gave way to private enterprise, which the Ming had vainly tried to stamp out. It is probable that leading merchants in China used their wealth to support the court faction opposed to state-sponsored trade.

The memory of Zheng He’s voyages lingered in Indian Ocean ports like Calicut and Malacca until the coming of the Portuguese in the early 16th century. When elderly inhabitants saw the bearded, light-skinned foreigners, they thought at first that the Chinese had returned. In China itself, the thousands of tons of pepper brought back by Zheng He’s treasure ships were used for years as currency, particularly to pay the army, in lieu of the traditional silk.

Had the Ming maintained their naval presence in the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese would have been faced with a formidable rival. In fact, their withdrawal helped make it relatively easy for the Portuguese, who made up in armaments what they lacked in numbers, to impose their will on the monsoon ports.

From the point of view of geographical discovery, the Ming voyages must rank as the earliest state-sponsored effort to seek out new lands, markets and spheres of political influence. That the same idea occurred to the rulers of both the Far East and the “Far West” almost simultaneously is intriguing, and it shows that—long before the emergence of a “global economy” in the late 20th century—East and West were responding to the same rhythms of political and economic change.

|

Historian and Arabist Paul Lunde studied at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies and specializes in Islamic history and literature. He is the author of Islam: Culture, Faith and History. With Caroline Stone, he has translated Mas‘udi’s Meadows of Gold and—forthcoming this fall from Penguin—Travellers From the Arab World to the Lands of the North, a collection of travel accounts. Lunde is a longtime contributor to this magazine, with some 60 articles to his credit over the past 33 years, including special multi-article sections on Arabic-language printing and the history of the Silk Roads, and the theme issue “The Middle East and the Age of Discovery” (M/J 92). He lives in Seville and Cambridge, England, and is working on an Internet project to map pre-modern Eurasian cultural and intellectual exchanges. He can be reached at paullunde@hotmail.com. |

< Previous Story | Next Story >