hen Ibn Battuta returned to Morocco toward the end of the year 1349, after nearly 20 years spent touring some 40 lands of the Middle and Far East, the stories he told were received with incredulity. Above all, it was his stories of the wealth of India that his listeners could not credit. Even the famous historian Ibn Khaldun, a man of great culture and experience, was sceptical:

hen Ibn Battuta returned to Morocco toward the end of the year 1349, after nearly 20 years spent touring some 40 lands of the Middle and Far East, the stories he told were received with incredulity. Above all, it was his stories of the wealth of India that his listeners could not credit. Even the famous historian Ibn Khaldun, a man of great culture and experience, was sceptical:

Most of all, [Ibn Khaldun wrote,] he talked of the ruler of India, saying things that were hard to believe. For example, he said that before going on a trip, the ruler would have a census made of every man, woman and child in the capital. Then he would give orders that all their needs for the next six months be paid out of his own personal income. The day of his return was a holiday and all the people went out into the countryside around the city and strolled about. Mangonels [catapults] fastened to the backs of elephants flung bags of silver and gold coins into the crowds until the ruler entered his audience hall. Ibn Battuta told a number of such stories, and court officials started to whisper that he was a liar.

It was at this time that I ran into Faris ibn Wadrar, the sultan’s well-known wazir. I told him I didn’t believe the man’s stories, especially since the court was generally agreed that he was a liar. But Faris said, “Don’t refuse to believe things about other dynasties just because you have not seen them for yourself. That would be like the son of the wazir who grew up in captivity…. When the boy attained the age of reason, he asked his father what kind of meat they had been eating. His father told him it was mutton. The boy asked what mutton was and his father described a sheep. ‘You mean, father,’ said the boy, ‘that it looks just like a rat?’ The same thing happened when they later ate beef and camel. Since the only animal the boy had seen in prison was a rat, he believed that all animals were like rats.”

It was at this time that I ran into Faris ibn Wadrar, the sultan’s well-known wazir. I told him I didn’t believe the man’s stories, especially since the court was generally agreed that he was a liar. But Faris said, “Don’t refuse to believe things about other dynasties just because you have not seen them for yourself. That would be like the son of the wazir who grew up in captivity…. When the boy attained the age of reason, he asked his father what kind of meat they had been eating. His father told him it was mutton. The boy asked what mutton was and his father described a sheep. ‘You mean, father,’ said the boy, ‘that it looks just like a rat?’ The same thing happened when they later ate beef and camel. Since the only animal the boy had seen in prison was a rat, he believed that all animals were like rats.”

Here, in the form of a fable that itself probably originated in India, is neatly encapsulated one of the major stumbling blocks to historical understanding. We are all prisoners of our own time and place, and we inevitably judge the new and strange in terms of the old and familiar. Thus, when Vasco da Gama returned to Lisbon in 1499, having discovered the sea route around Africa to India, he jubilantly announced to King Manuel that the inhabitants of the west coast of India were Christians: After all, he had visited their churches in Calicut and witnessed their devotion to the image of the Virgin Mary.

|

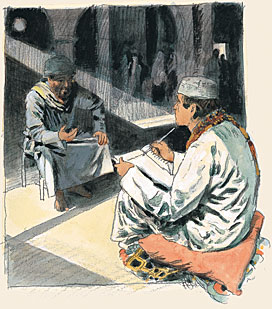

Ibn Battuta dictated his Rihla, the account of his 20 years of travels, in 1354 and 1355. Some of his stories went far beyond what even his sophisticated listeners could believe.

NORMAN MACDONALD |

We may smile at Vasco da Gama’s enthusiastic identification of the Hindu goddess Durga with the Virgin Mary, but errors are inevitable when dealing with cultures remote from our own. Ma Huan, Arabic interpreter to the Chinese admiral Zheng He on his remarkable voyages to the Indian Ocean in the early years of the 15th century, says the ruler of Calicut was a Buddhist. There is no doubt that Ma Huan, a careful and reliable observer in other respects, witnessed the king at his devotions. He knew that, in the distant past, Chinese pilgrims had visited India to study Buddhism and, unaware that Buddhism had long since ceased to be practiced in India, Ma Huan simply confused an image of Vishnu with that of Buddha.

The chances of misinterpretation are even greater when to geographical, cultural, religious and linguistic remoteness, we add remoteness in time. We are separated by 500 years from Vasco da Gama and Ma Huan, and by almost 2000 years from the Greeks, the earliest Europeans to trade in the Indian Ocean. We are almost unimaginably more distant from the men who first sailed these waters, the speakers of Austronesian languages who, beginning around 5000 years ago, populated Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, the Indonesian islands, Madagascar and the islands of the remote Pacific.

The past is like a long archipelago that recedes over the horizon. The nearest islands are mapped, those in the middle distance are partially explored, and the farthest are known only by hearsay. The sea that divides island from island corresponds to the intervals of our ignorance, which are plentiful, for the historical record is anything but continuous,

and the majority of the islands lie beyond the horizon

and beyond our ken, shrouded in the mists of prehistory.

To avoid mistaking a sheep for a rat, like the son of

the wazir in the fable, we must bear in mind that the very diverse inhabitants of these metaphorical islands were quite unlike us, the men and women who inhabit the mainland of the early 21st century. It is true that we have something in common with the inhabitants of the nearest islands, corresponding to the 20th, 19th and 18th centuries, for

we are still affected by the political and economic consequences of their activities.

But as we voyage farther into the past, to the 15th century—the age that produced men like Zheng He, Ahmad ibn Majid, Vasco

da Gama and Columbus—there are fewer familiar landmarks. They are at the edge of our understanding, their minds difficult to grasp and the worlds they moved in not like ours. They have all acquired a mythic dimension that makes their true character and achievements hard to assess. For example, Chinese legend credits Zheng He, admiral of the Ming fleets that explored the waters of the Indian Ocean, with being some three meters (10') tall and possessing superhuman strength. He was venerated as a god, and his life was made the subject of an adventure novel filled with wonders. The Arab navigator Ahmad ibn Majid was thought by some to have been the pilot who single-handedly unlocked the secrets of the monsoon for Vasco da Gama, guiding him from the coast of East Africa to Calicut. Later generations of Arab seamen remembered Ibn Majid as the greatest navigator of them all, and invoked his name before making the perilous crossing of the Red Sea between Aden and the Horn of Africa.

Vasco da Gama and Columbus too are culture heroes, having in common obscure early lives and extraordinary later achievements. The blank spaces in their biographies have been filled by generations of ingenious historians, each transferring his national and personal predilections to his subjects. Thus Samuel Elliot Morrison portrayed Columbus as a hard-headed, practical mariner, impatient of authority, his aims misunderstood by uncomprehending bureaucrats:

a kind of proto-Yankee—a man, one feels, very like Samuel Elliot Morrison. Yet Columbus, as we know from the version of his logbook that has come down to us, from his occasional letters and from the marginalia in his surviving books, avidly read prophecies, hourly expected the end of the world, sought the Earthly Paradise and was convinced to the end of his days that he had discovered not a new world, but Marco Polo’s Cathay. The European search

for a sea route to India was the working out of a medieval dream, with its roots in biblical and classical tradition, and the men who carried it out were only chronologically men of the Renaissance.

As we move a little deeper into time, things become stranger still. The map begins to blur. It is no longer easy to match the places named in the fragmentary texts we possess to the places we know. Yet these islands of our imaginary archipelago correspond to the period of Islamic expansion into the waters of the Indian Ocean, roughly the years AD 750 to 1500. This era of intense maritime activity saw the establishment of Muslim communities in China,

India, Southeast Asia, East

Africa, Madagascar and

the Philippines. Muslim merchants and shipowners held a virtual monopoly of the maritime transport trade in the western reaches of the Indian Ocean, trading in spices, aromatic gums, dye woods, tortoiseshell, precious gems, textiles, silk, timber, horses, rice, coir, metals and pharmaceuticals, as well as such bulk cargoes as grains, vegetable oils and dried fish. Muslim traders established merchant colonies in Chinese ports like Canton and Hangzhou. A complex system of Asian trading networks gradually developed on sea and land, one that involved merchants of many different faiths—Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, Jews, Muslims—and a bewildering variety of ethnic and linguistic groups, including not only Arabs and Persians and Chinese but also Gujaratis, Malabaris, Cholas, Kelings, Bengalis, Malays, Indonesians, Bugis and East Africans.

Yet this extraordinary process of development is but poorly documented. It was the work of generations of private individuals of the most varied origins and motives, all of whom were governed, nonetheless, not by any one state or ruler, but by the iron regime of the monsoon.

|

Historian and Arabist Paul Lunde studied at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies and specializes in Islamic history and literature. He is the author of Islam: Culture, Faith and History. With Caroline Stone, he has translated Mas‘udi’s Meadows of Gold and—forthcoming this fall from Penguin—Travellers From the Arab World to the Lands of the North, a collection of travel accounts. Lunde is a longtime contributor to this magazine, with some 60 articles to his credit over the past 33 years, including special multi-article sections on Arabic-language printing and the history

of the Silk Roads, and the theme issue “The Middle East and the Age of Discovery” (M/J 92). He lives in Seville and Cambridge, England, and is working on an Internet project to map pre-modern Eurasian cultural and intellectual exchanges. He can be reached at paullunde@hotmail.com. |

Next Story >