went down to Basra with a group of merchants and companions, and we set sail in a ship upon the sea, and at first I was seasick because of the waves and the motion of the vessel, but soon I came to myself and we went about among the islands, buying and selling.”

went down to Basra with a group of merchants and companions, and we set sail in a ship upon the sea, and at first I was seasick because of the waves and the motion of the vessel, but soon I came to myself and we went about among the islands, buying and selling.”

—The Tale of Sindbad the Sailor, from The 1001 Nights

|

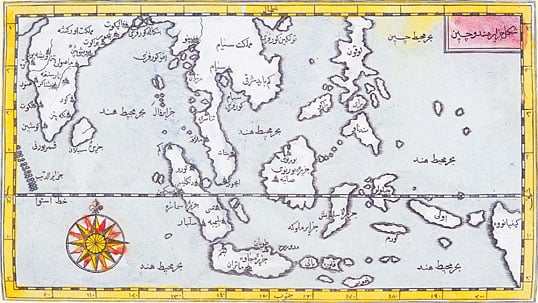

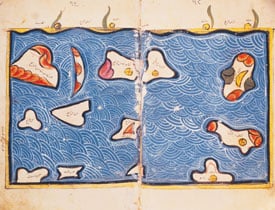

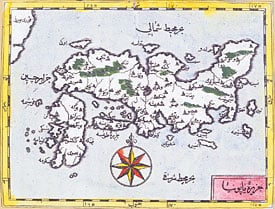

| This map of the Indian Ocean and the China Sea was engraved in 1728 by the Hungarian-born Ottoman cartographer and publisher Ibrahim Müteferrika; it is one of a series that illustrated Kâtib Çelebi’s Cihannuma (Universal Geography), the first printed book of maps and drawings to appear in the Islamic world. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY |

Besides sailing across the Indian Ocean, there was another sea route from Arabia to India, the oldest of them all. It was not dependent on the monsoon and could be sailed without knowledge of the stars. The Arabian Gulf was the natural corridor between Mesopotamia and India, and the voyage could be made in small boats simply by hugging the coast, always keeping land in sight. Maritime contacts between Mesopotamia and India through Gulf waters go back to the very beginnings of urban civilization in the third millennium BC, when Sumer on the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers was in touch with Harappa on the Indus.

Unlike the Red Sea, whose reef-filled waters and complex wind regime required skilled pilotage, the Arabian Gulf was relatively easy to navigate. While the shores of the Red Sea were sparsely inhabited and almost waterless, the headwaters and eastern shore of the Gulf were home to ancient civilizations. Along its coasts have been found the scattered evidence of some five millennia of trade: fragments of pre-Sumerian al-‘Ubaid pottery from the third millennium BC, Chinese celadon and early Islamic glazed jars, Indian bangles, Gujarati carnelian beads, 19th-century coffee cups, Roman coins and the occasional Chinese cash.

On the western shore, in the second century BC, at around the time that Hippalos discovered the secret of the monsoon, the caravan city of Gerrha flourished in what is now the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Strabo, quoting a source named Artemidorus, says: “From their trafficking both the Sabaeans and the Gerrhaeans have become richest of all; and they have a vast equipment of both gold and silver articles, such as couches and tripods and bowls, together with drinking vessels and very costly houses; for doors and walls and ceilings are variegated with ivory and gold and silver set with precious stones.”

|

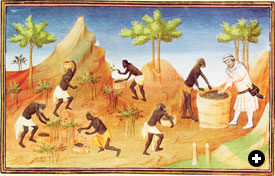

| The city of Cambay was an important Indian manufacturing and trading center noted by Marco Polo and illustrated here in the 15th century. BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE / ARCHIVES CHARMET / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY (BOUCICAUT MASTER) |

Although no certain traces of Gerrha have yet been found, it has been identified tentatively with the site known as Thaj, while its name may be preserved in that of the little port of al-‘Uqair not far away.

At the head of the Gulf was the port the Greeks called Apologos and the Arabs called al-Ubulla; it was conquered in the year 636 by ‘Utba ibn Ghazwan, who, in a letter to the Caliph ‘Umar informing him of his victory, called it “the port of Bahrain, Oman and China.” We see that in the five hundred or so years since the composition of the Periplus, a significant change had taken place: The sea route to China, a country known to the classical world only by hearsay, had been discovered.

Basra, a military camp near al-Ubulla in 638, quickly grew into the largest and most ebullient city in the Islamic world, its population exploding from zero to 200,000 in three decades. The streets were thronged with Arabs, East Africans, Persians, Indians and Malay-speakers from “Zabaj” (Indonesia). A clearinghouse for information, it was here that practical knowledge of Southeast Asia and China began to reach the Arabic-speaking peoples and gradually find its way into both sober works of geography and entertaining wonder books. Basra’s most famous writer, the ninth-century polymath al-Jahiz, reflected the excitement of the city’s intellectual world: “Our sea is worth all the others put together,” he wrote, “for there is no other into which God has poured so many blessings. It flows into the Indian Ocean, which extends for an unknown distance.”

During the half millennium between the Periplus and the founding of Basra, most of the references to trade with the Far East emanate from Nestorian Christian sources. Persecuted in Byzantine lands for their unorthodox beliefs, the Nestorians took refuge in Sasanian Persia, where the Sasanians, inveterate enemies of the Byzantines, welcomed them. The Nestorians were active proselytizers, and, like other marginalized minorities in largely agrarian Asian states, they turned to trade. They followed the overland Silk Roads from Persia into Central Asia and ultimately to China. Nestorian communities were established on the west coast of India—where they were encountered by the Portuguese a millennium later—as well as in Sri Lanka, Socotra and Yemen.

During the half millennium between the Periplus and the founding of Basra, most of the references to trade with the Far East emanate from Nestorian Christian sources. Persecuted in Byzantine lands for their unorthodox beliefs, the Nestorians took refuge in Sasanian Persia, where the Sasanians, inveterate enemies of the Byzantines, welcomed them. The Nestorians were active proselytizers, and, like other marginalized minorities in largely agrarian Asian states, they turned to trade. They followed the overland Silk Roads from Persia into Central Asia and ultimately to China. Nestorian communities were established on the west coast of India—where they were encountered by the Portuguese a millennium later—as well as in Sri Lanka, Socotra and Yemen.

To the southwest of the Arabian Peninsula, across the Red Sea, lay the Ethiopian Christian kingdom of Aksum, with its port of Adulis. Aksum exported gems, spices—including cassia—incense and gold to Byzantium, India, Sri Lanka and Persia. The gold came from the African interior and the incense was grown in Aksumite territory, but the cassia and other spices almost certainly came from India and what is now the Indonesian archipelago.

The Ethiopic liturgical language, Ge’ez, was derived from one of the non-Arabic Semitic languages of South Arabia. Its alphabet is the only Semitic alphabet to indicate vowels, and the system by which it does this is elsewhere found only in the various writing systems of India—further evidence of the extent to which ideas as well as spices were trafficked across the Indian Ocean.

Between 540 and 570, two events occurred that had profound effects on Arabian society. The great dam of Ma’rib in Yemen, which had supported the South Arabian agrarian kingdoms of Saba and Himyar, burst, either through neglect or because of some unrecorded natural disaster. The huge area it had irrigated was laid waste. The fall of these South Arabian kingdoms was to Arab tradition what the fall of Rome was to the early Christians: the end of an old era and the beginning of a new one.

The other important event was the Sasanian Persian invasion of Yemen, which was at that time ruled by Ethiopia. At the request of Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan, scion of an old Yemeni aristocratic house, the Sasanian fleet landed at Aden and the Ethiopians were exterminated. The fabulous palace of Ghumdan at San‘a, with its ceilings of translucent alabaster so thin that the shapes of flying birds could be discerned through it, was destroyed. The historic connection between the African and Arabian shores of the Red Sea was severed, and the wealth of Aksum was no more. The port of Adulis vanished. The Christians of Ethiopia withdrew to the highlands, where they preserved their distinctive culture in isolation, inadvertently giving rise to the legend of the kingdom of Prester John.

Shortly after the death of the Prophet in 632, the Islamic conquests put an end to the Sasanian dynasty. In the year 711, Muslim armies invaded both Spain in the far West and the province of Sind, roughly corresponding to modern Pakistan, in the East. In 751 the Muslims defeated a Chinese army at Talas, north of the Oxus River, in what is now Kyrgyzstan. The Byzantine Empire, too, suffered: It lost its provinces in Syria, Egypt and North Africa to the Muslims.

Byzantium, India and China were suddenly neighbors of a new world empire, with a new religion—Islam—and a unifying language—Arabic. Persia, the historic enemy of Greece and Rome, was reduced to a province of an Arab empire.

|

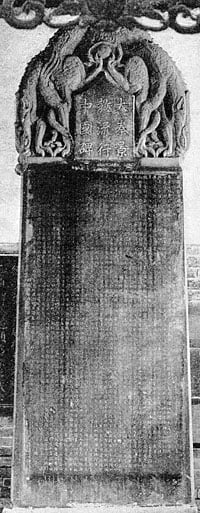

| This stele, erected in 781 in Xi’an, includes a list of 70 Nestorians who, with Arabs and Persians, were active traders in China during Umayyad and Abbasid times. FRITS HOLM / PAUL CARIS, ED.: THE NESTORIAN MONUMENT, CHICAGO, 1909 / COURTESY DANIEL WAUGH, SILK ROAD SEATTLE |

In pre-Islamic times, Sasanian Persia had blocked direct contact between China and the Byzantine empires. Chinese silks and ceramics had reached the West overland almost exclusively through Persia. Exactly when maritime trade with China began is unknown. A Chinese work called the Chhien Han Shu mentions trade with the “South Seas” in the first century BC and speaks of voyages lasting a year. Whether these voyages terminated in India or crossed the Indian Ocean to the Arabian Gulf or Red Sea is unknown, but there is little doubt that Chinese ships at this time reached Malaya, the traditional halfway house between what was in pre-Islamic times the Chinese-dominated Pacific and the Indian-dominated Indian Ocean.

That there were Arab and Persian merchants domiciled in Chinese ports in the immediately pre-Islamic period is indicated by the words used to refer to them in Chinese annals. Persians were called Po-ssu, Arabs Ta-shih. Po-ssu is obviously an attempt to render the word Pars, which gave rise to the Greek Perses, the Latin Parthia and the Arabic Fars. Ta-shih is derived from the Aramaic name of the Arab tribe of Tayy, which must have reached China via Aramaic-speaking Nestorian merchants from the region of al-Hira, where this tribe was dominant.

The traditional date for the introduction of Nestorian Christianity to China is 636, the date given on the beautiful black stone stele erected in 781 at the Tang capital of Xi’an in central China. The text consists of 1900 Chinese characters that give an account of the event, while a short inscription in Syriac, the language used by the Nestorians, gives a list of 70 Nestorian missionaries. Only a few years after the stele was raised, the Tang annals speak of 2000 Arab and Persian merchants trading in Canton: Clearly, the sea route between the Middle East and China was wide open.

The discovery of the sea route between the Arabian Gulf and China was an event equal in importance to the discovery by the Portuguese of the sea route to India. It was one thing to cross the Indian Ocean with the monsoon to Gujarat or the Malabar coast, or even to sail south of Sri Lanka and turn north to the Bay of Bengal or east to Malaya—but it was quite another to make the far longer voyage to Canton through a lesser-known sea with its own pattern of winds, to say nothing of the perpetual danger of piracy and the typhoons of the South China Sea. Yet in early Islamic times, direct sailing to Canton via the Gulf seems to have been common practice.

|

| Pepper, shown here being harvested in Coilum in southern India, was one of the most profitable trade items shipped to Europe. However, the romance of the spice trade makes it easy to forget that the bulk of Indian Ocean shipping was devoted to cargoes like rice, hardwoods, tin, iron ore, horses, rope, textiles and other daily essentials. BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE / ARCHIVES CHARMET / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY (BOUCICAUT MASTER) |

The bahr al-hind, the “Sea of India,” or the bahr al-sin, the “Sea of China,” as the Indian Ocean was often called, was not a single entity. Those who sailed it said it was made up of seven different seas, each with its own characteristics—the traditional division from which we derive our expression for far-ranging travel, “to sail the seven seas.”

Here is how al-Ya’qubi, who died in 897, describes it, obviously following oral tradition:

Whoever wants to go to China must cross seven seas, each one with its own color and wind and fish and breeze, completely unlike the sea that lies beside it. The first of them is the Sea of Fars, which men sail setting out from Siraf. It ends at Ra’s al-Jumha; it is a strait where pearls are fished. The second sea begins at Ra’s al-Jumha and is called Larwi. It is a big sea, and in it is the island of Waqwaq and others that belong to the Zanj. These islands have kings. One can only sail this sea by the stars. It contains huge fish, and in it are many wonders and things that pass description. The third sea is called Harkand, and in it lies the island of Sarandib, in which are precious stones and rubies. Here are islands with kings, but there is one king over them. In the islands of this sea grow bamboo and rattan. The fourth sea is called Kalah-bar and is shallow and filled with huge serpents. Sometimes they ride the wind and smash ships. Here are islands where the camphor tree grows. The fifth sea is called Salahit and is very large and filled with wonders. The sixth sea is called Kardanj; it is very rainy. The seventh sea is called the sea of Sanji also known as Kanjli. It is the sea of China; one is driven by the south wind until one reaches a freshwater bay, along which are fortified places and cities, until one reaches Khanfu [Canton].

The names of these seven seas derive from the languages of the peoples who lived on their shores. The names preserve, as if in amber, the varied linguistic and cultural backgrounds of the seafarers who first explored these waters, and they sounded just as exotic to Arabic-speakers in the ninth and 10th centuries. These are the seas sailed by Sindbad in The 1001 Nights, for the stories of his adventures almost certainly date from the ninth or 10th century; they give a vivid picture of the dangerous and mysterious world of these early mariners. The little book by Buzurgh ibn Shahriyar, ‘Aja ’ib al-Hind (The Wonders of India), written in the 10th century, is a compendium of seafaring tales remarkably similar in tone to the adventures of Sindbad.

|

| This 12th-century map of the Indian Ocean by al-Idrisi is so obviously imprecise as to seem almost decorative. (Note its similarity to the islands of the Indian Ocean in his world map) But don’t fault him for trying: It was one thing to be able to sail all the way to China and quite another to explain to a stay-at-home scholar where one had been. It is easy to forget what an achievement even a simple map represented. Until the 15th century, mariners knew maps could indicate relative shapes and sizes, but they were nearly useless for navigation. NATIONAL LIBRARY, CAIRO / GIRAUDON / ART RESOURCE |

The most important surviving document on international trade in the ninth century is a brief account by Ibn Khurradadhbih, a director of the government postal service in Baghdad, called Kitab al-Masalik wa ’l-Mamalik (Book of Roads and Kingdoms). It describes the overland and maritime routes that linked the Abbasid Empire to the world, including a description of the sea routes to India, Malaya, Indonesia and China. Most interestingly, Ibn Khurradadhbih’s account describes regular, organized long-distance trade between western Europe and China long before the days of Marco Polo.

One of his most interesting passages describes a group of international traders called the Radhaniyya, who were Jewish merchants from the “land of the Franks,” that is, the Carolingian Empire. Their name may be derived from the Latin name of the river Rhône, and their most probable home port is Venice:

These merchants speak Arabic, Persian, Greek, Latin, Frankish, Spanish and Slavic, [Ibn Khurradadhbih wrote.] They travel from West to East and from East to West, sometimes by land, sometimes by sea. From the West they bring eunuchs, female slaves, young boys, brocades, beaver, marten and other furs and swords. They set sail from the land of the Franks, on the Western Sea [the Mediterranean], and make for al-Farama [on the Isthmus of Suez]. There they transfer their merchandise to camels and go overland to [the Red Sea port of] Qulzum, a distance of 25 farsakhs. From there they set sail on the [Red Sea] and make for al-Jar and Jiddah. Then they sail to Sind, India and China. On their return from China, they bring musk, aloeswood, camphor, cinnamon and other products of the East. They return to Qulzum, then back to al-Farama, where they take ship once again on the [Mediterranean] Sea. Some sail to Constantinople, to sell their merchandise to the Greeks; others go to the capital of the king of the Franks to sell their goods. Occasionally these Jewish merchants sail from the land of the Franks to Antioch. From there they go to al-Jabiyah, three days overland. There they embark on the Euphrates, making for Baghdad. Then they go down the Tigris to al-Ubulla. From al-Ubulla they set sail for Oman, Sind, India and China.

Of the four routes of the Radhaniyya merchants he mentions, two are overland and two are maritime. They coincide with trade routes described in other Arabic sources.

But some scholars have been skeptical about the existence of a “Radhaniyya network.” Other sources, most notably the correspondence of Jewish merchants from Egypt preserved in the Cairo Genizah, a fundamental source for our knowledge of medieval commerce, show that the great majority of merchants confined their activities to their own regions, seldom making long journeys themselves. Long-distance trade consisted of a chain of interregional trips rather than the long and inevitably perilous journeys described by Ibn Khurradadhbih. This is certainly true for the period after about 1000, when the trade networks were denser and more organized; however, we have already seen that earlier maritime trade with China was indeed direct. The Wonders of India tells of a ship’s captain from Siraf who made seven voyages to Canton and back, all before the middle of the 10th century.

|

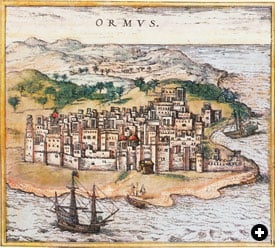

| The position of the city of Hormuz, set on the strait at the bottom of the Arabian Gulf, was no less strategic in the days of Indian Ocean sailing, when it controlled traffic between Gulf ports and the East, than it is today. BRAUN AND HOGENBERG, CIVITATES ORBIS TERRARUM, 1572 (2) |

The 10th-century Baghdadi historian al-Mas‘udi, in his Muruj al-Dhahab (Meadows of Gold), explains how direct voyages to China were replaced with a system in which merchants stopped at a halfway house in either Sri Lanka or Malaya, where they purchased goods brought there from China:

China was prosperous because of the justice with which the country was administered, as it always had been under its former kings, until the year 878. From that year until our own days [943], events have occurred which upset order and overturned the authority of the law. A rebel named Huang Ch’ao…ravaged the cultivated lands of the kingdom and set up his camp before Canton an important city situated on a river larger and more important than the Tigris. This river flows into the Sea of China, six or seven days’ journey from Canton. Ships from Basra, Siraf and Oman and other kingdoms sail up it with their merchandise and cargoes. Huang Ch’ao besieged Canton and chopped down the mulberry groves which surrounded the city and had fed the silkworms that produced the silk that was exported to Islamic countries. Silk production and export came to a halt. He took Canton and slaughtered 200,000 Muslims, Christians, Jews and Mazdaeans. This estimate could not have been made except for the custom of Chinese kings of keeping census lists of their subjects and neighboring nations tributary to them. They have officials charged with making the census, for they wish to have an up-to-date idea of the number of their subjects.

Everything in al-Mas‘udi’s account is confirmed by Chinese annals—though the number of casualties among the merchants is clearly much exaggerated—and it serves to give an idea of the importance of Canton in international trade at the time. Its note of Jews among the merchants killed gives credence to Ibn Khurradadhbih’s account of the Radhaniyya.

As a result of Huang Ch’ao’s sack of Canton and the political uncertainty in southern China in the wake of his rebellion, the pattern of maritime trade changed. Al-Mas‘udi’s informant on Chinese affairs, the Sirafi merchant Abu Zayd, told him, “Today the city of Kalah [in Malaya] is the terminus for Muslim vessels from Siraf and Oman. Here they meet the ships from China. But this was not so in the past. Formerly, ships from China sailed directly to Oman, Siraf, the coast of Persia and Bahrain, al-Ubulla and Basra, and ships from these places sailed directly to China. It is only since people could no longer trust in the justice of governments and in their good intentions and since the state of China has become what we have described that merchants meet at this intermediate point.”

|

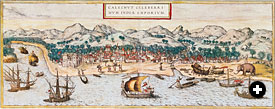

| A panorama of Calicut, on the Malabar coast, shows several types of ships, shipbuilding, net fishing, dinghy traffic and a rugged, sparsely populated interior. BRAUN AND HOGENBERG, CIVITATES ORBIS TERRARUM, 1572 (2) |

These political events in China reverberated in the Arabian Gulf. The sack of Canton occurred in the very years that all of lower Iraq was in the throes of the Zanj Rebellion, the 20-year insurgency of slaves from East Africa who worked in the nitrate beds in the marshes of Lower Iraq. During this period, Basra, al-Ubulla and Abadan were dangerous places. Just as traders had moved away from Canton, so they moved south down the Gulf out of harm’s way. They settled in Siraf, a small town on the Persian side controlled by men from Oman. Siraf became the main port for the eastern trade, and Basra never reclaimed its former position.

The classical pattern of Asian maritime trade was now set. First Siraf, then a series of other Gulf ports on both the Persian and Arabian sides, ending with Hormuz, became major emporia. The Malay-speaking peoples of Malaya and the Indonesian archipelago became the intermediaries between Islam and China, as Kalah and other ports became the nuclei of local dynasties that in time became Muslim. East of the Strait of Malacca, the seas were dominated by Chinese shipping. Indian shipping continued to play a most important role, and ships from Gujarat, Malabar and Bengal plied the waters of the Indian Ocean. But the days of direct sailing between China and the Arabian Gulf were over.

The new system lasted for nearly five centuries, until the coming of the Portuguese. Although it began as a reaction to unstable political situations, other factors were at work as well. One was speed: Moving ports ever closer to the margins of the monsoon winds reduced sailing time, diminished the ever-present danger of shipwreck and allowed more goods to flow. By establishing emporia halfway to China, in ports like Kalah and later Malacca, the year-long voyage to China could be halved. Reducing the turnaround time made it possible to meet increasing demand, as markets expanded in both the Muslim world and in Europe. These emporia often enjoyed semi-independent or even fully independent status, also a major attraction to merchants.

The key figure in the system remained the small trader who, like Sindbad, risked his life and capital to set sail upon the Indian Ocean, to “go about among the islands, buying and selling.”

In a passage about the sea route to China in his Kitab al-Masalik wa ’l-Mamalik (Book of Roads and Kingdoms), Ibn Khurradadhbih gives an estimate of the size of the Indian Ocean: “The length of this sea, from Qulzum [at the head of the Red Sea] to Waqwaq, is 4500 farsakhs.” He also states that the distance from Qulzum to the Mediterranean port of Farama is 25 farsakhs. The latter distance, he writes, corresponds to the length of one degree on the meridian; thus, the 4500-farsakh distance to Waqwaq corresponds to 180 degrees. Therefore Waqwaq lies exactly halfway around the world from Qulzum. With its outlandish name and incredible distance eastward, Waqwaq seems to belong to legend rather than commercial geography.

Yet Ibn Khurradadhbih clearly thought Waqwaq was a real place. He mentions it twice more: “East of China are the lands of Waqwaq, which are so rich in gold that the inhabitants make the chains for their dogs and the collars for their monkeys of this metal. They manufacture tunics woven with gold. Excellent ebony wood is found there.” And again: “Gold and ebony are exported from Waqwaq.”

So where was Waqwaq?

Ibn Khurradadhbih’s first European editor, the Dutch scholar Michael Jan de Goeje, noted that one of the Chinese names for Japan was wo-kuo, “the country of Wo.” In the Cantonese dialect, which Arab merchants would have heard, this is pronounced wo-kwok. The mystery was solved: “Waqwaq” was an almost perfect rendering of a Chinese name for Japan.

|

| Was “Waqwaq” Japan? Ibn Khurradadhbih mentions it as lying “east of China,” but nothing else in his description seems to apply to Japan, and no other early Muslim geographer mentions the country. By Müteferrika’s time, however, Japan was well enough knows for a tolerable depiction of it to appear in the Cihannuma. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY |

This solution was doubly satisfying, for it solved the mystery of Waqwaq and proved, for the first time, that the Arabs knew of Japan. The trouble with de Goeje’s identification, however, is that nothing Ibn Khurradadhbih says about Waqwaq seems to have anything to do with Japan. Although “tunics woven with gold” are barely possible, it is difficult to imagine monkeys and dogs with golden collars in the sophisticated, austere society of ninth-century Japan. Nor does Japan export ebony.

“Waqwaq” was also the name of an unusual tree. The earliest reference to it (though without the name) occurs in a Chinese source, the T’ung-tien of Ta Huan, written before 801. Ta Huan was told the story by his father, who had lived in Baghdad for 11 years as a prisoner of war after the Battle of Talas. He claimed to have heard the following story from Arab sailors:

The king of the Arabs had dispatched men who boarded a ship, taking with them their clothes and food, and went to sea. They sailed for eight years without coming to the far shore of the ocean. In the middle of the sea, they saw a square rock; on this rock was a tree with red branches and green leaves. On the tree had grown a number of little children; they were six or seven thumbs in length. When they saw the men, they did not speak, but they could all laugh and move. Their hands, feet and heads were fixed to the branches of the trees.

The same story occurs repeatedly in Arabic sources, where the tree is identified as “the waqwaq tree,” and is later embellished by turning the little children into beautiful young women, suspended from the branches by their hair. The classic account, written in 12th- century al-Andalus, says the women “are more beautiful than words can describe, but are without life or soul…. This is a wonder of the land of China. The island is at the end of the inhabited world….”

Two accounts, however, do not fit with the others. One describes a fairly advanced culture: “I have been told by some people that they met a man who had traveled to Waqwaq and traded there. He described the large size of their towns and their islands. I do not mean by this their area, but the size of their population. They look like Turks. They are very industrious in their arts and everywhere in their country they try to improve their ability.”

The other is much more intriguing:

In the year 945 the people of Waqwaq sailed with 1000 ships to attack Qanbaluh [on the coast of East Africa, opposite Zanzibar]…. When asked why they attacked them, rather than some other city, they answered that it had things needed in their own country and also in China, such as ivory, tortoiseshell, panther skins and ambergris; besides, they wanted to capture men of Zanj, who are strong and able to stand hard labor. They said their voyage lasted a year…. If these men were telling the truth when they said they had sailed for a year, then Ibn Lakis was right when he says the islands of Waqwaq are opposite China.

De Goeje, who knew this text and was still convinced that Waqwaq was Japan, tried without success to find historical evidence of a Japanese naval assault on East Africa in 945. The French scholar Gabriel Ferrand, who first identified Waqwaq with Madagascar, then with Sumatra, wondered with more reason if this were not an account of an Indonesian attack on Madagascar and the East African coast, or even a memory of the aggressive migration of speakers of Austronesian languages from the Indonesian archipelago to Madagascar. (See page 16, “The Question of Madagascar.”)

Al-Biruni, who wrote his wonderful book Kitab al-Hind (The Book of India) in AD 1000 based largely on Sanskrit sources, mentions a country where people are born from trees and hang suspended from the branches by their navels. Perhaps the waqwaq tree too goes back to a Sanskrit source, and the Arab tales of Waqwaq are themselves a faint memory of a time when the Indonesian archipelago was in the cultural orbit of Hindu–Buddhist culture.

The story of the waqwaq tree traveled westward, like many other oriental stories, appearing in at least one of the surviving manuscripts of the 14th-century traveler Friar Odoric and in one of the many medieval French romances of Alexander the Great. Its final appearance dates from 1685, when all the mysteries of the Indian Ocean had long faded in the light of pragmatic European accounts. It occurs in the Safinat Sulayman (The Ship of Solomon), an account of a Persian embassy to Siam (now Thailand) written by a scribe who accompanied the mission. He says he heard it from a Dutch captain:

Once on our way to China we dropped anchor in the bay of an island to avoid a heavy storm. There was a strange collection of people inhabiting the island who only barely resembled human beings. Their feet were three cubits long and just as wide and they were completely nude and had very long hair. At night they all climbed to the top of their own trees in the jungle, even the women, who bore their children with them under their arms. Once up in the tree they would tie their hair to a branch and hang there all night resting.

Nothing shows the medley of cultures of the Indian Ocean so well as the story of the waqwaq tree: It probably originated in a Sanskrit Hindu text, was told in the eighth century to a Chinese envoy by an Arab sailor, was brought to Europe by a Franciscan friar and was retold by a Dutch sea captain to a Persian envoy to the king of Siam. |

Beyond the mouth of the Gulf, past Ra’s al-Hadd, the Sea of Larwi begins. Beware, the way is barred by sea monsters upon whose backs grass and seashells grow. Mariners have taken them for islands and come to grief. They blow water into the air, high as a minaret, and when the sea is calm, sweep whole schools of unwary fish into their gaping mouths with their tails. Sailors beat wooden clappers at night to keep them at bay.

These monsters are not the same as the wal, which is 20 cubits long. When caught and slit open, a smaller version of itself is found inside, and this in turn contains another. Despite its size, the wal is preyed upon by a fish called laskh, no more that a cubit long. When the wal misbehaves, maltreating smaller fish, the laskh penetrates its ear and kills it. The laskh attaches itself to the hulls of ships; such ships are safe, for no wal dares approach. Then there are the flying fish with human faces, called mij. When they fall back into the sea, they are devoured by the fish called ‘anqatus. For all fish eat each other.

|

| Above: Cowry shells were harvested by the hundreds of thousands in the Maldives. Below: Coir was prized by mariners because it resisted salt and sun better than any other cordage. ABOVE: RONALD SHERIDAN / ANCIENT ART & ARCHITECTURE COLLECTION; BELOW: JOSEPH E. ARMSTRONG |

|

The Sea of Larwi is separated from the Sea of Harqand by an archipelago of 1900 islands. They are closely spaced, the distance between islands being two, three or four farsakhs. They are small, but inhabited and ruled by a queen. The coconut palm thrives; pieces of ambergris the size of a house are thrown up on shore from the bottom of the sea. Wealth is measured in cowry shells, which are stored up in the royal treasury. The local name for them is kastaj. The people of these islands are expert weavers. They make long chemises with sleeves, side panels and pockets, all woven in a single piece. Their houses, boats and other things are made with equal skill.

This is a paraphrase from the oldest firsthand Arabic account of India, island Southeast Asia and China, Akhbar al-Sin wa ’l-Hind (Notes on China and India), which dates from 851.

The ninth-century reader would have been struck no less than we are by the number of outlandish words in these three short paragraphs, and the use of all these exotic words is the author’s literary device to prefigure the unfamiliarity of the region he was describing.

The voyage described in the Notes begins in the mysteriously named Sea of Larwi and immediately enters a stranger and more threatening environment than the familiar waters of the Arabian Gulf. The first landfall is an archipelago—its name is later given as Dibajat—that is ruled by a woman, where wealth is counted not in gold or silver but in cowry shells, a gift of the sea. Just as Dibajat is outside the patriarchal system of Islamic lands, it is outside the bimetallic monetary system. Yet the inhabitants are far from primitive; they are skilled craftsmen and weavers, though they flourish far from cities. A civilization without cities is a contradiction in terms, and the author is warning the reader that his mental categories must be adjusted.

Even the naïve anecdotes about sea monsters make a point about appearance and reality, warning us not to accept a foreign environment at face value: What appears to be an island may turn out to be the back of a sea monster. The story of the wal, that when opened contains smaller replicas of itself, illustrates a different point of the author’s: We are continually faced with reflections of our own beliefs. The vulnerability of the wal to the little lashk shows the fragility of power—something to be borne in mind when considering the vulnerability of the small trading emporia perched along the coasts of the great land-based, agricultural empires of India and China.

With the force and simplicity of a proverb, a predator-prey model of marine life is presented: “For all fish eat each other.” The reader would have been expected to draw the parallel with human society.

The writer’s “archipelago of 1900 islands” is in fact the Laccadives and Maldives, 10 days’ sail west of Calicut; their actual 2000-plus coral atolls stretch 1500 kilometers (900 mi) north to south, like a net deployed to catch ships. Five hundred years after the author of the Notes wrote down his metaphorical and fantastic tale, the Maldives and their waters were well integrated into the system of Indian Ocean trade. Ibn Battuta called them “one of the wonders of the world,” and remarked on their annular form and proximity to each other: “A hundred or so are arranged in a circle like a ring, with an opening at one point to form a passage; ships may reach the islands only through this passage…. They are so close together that when leaving one, the tops of the palm trees on the next are visible.”

|

| This detail from an 18th-century map by Pierre Mortier of The Netherlands names several dozen of the Maldive Islands off the southwestern coast of India. BUKHARI COLLECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS OF ARABIA |

In historical times, the Maldives have successively been Hindu, Buddhist and Muslim. Unusually, we have a precise date for the introduction of Islam there—July 1153—confirmed by an inscription in the Friday Mosque on Male, the principal island, and by an 18th-century Arabic history of the Maldives, the Ta’rikh Islam Diba Mahal by the jurist Hasan Taj al-Din. The latter states that the Buddhist ruler, Siri Bavanaditta Maha Radun, embraced Islam as the result of a miracle performed by a pious Muslim who was visiting the islands.

“A strange thing about these islands,” wrote Ibn Battuta, “is that their ruler is a woman.” So by a curious chance, a queen held power there again, 500 years after the Akhbar al-Sin wa ’l-Hind was written. Ibn Battuta calls her Sultana Khadija, but her Maldivian name was Rehendi Kambadikilage; she was 19th in the line of the ruling Theemuge dynasty. She ruled from 1347 to 1362, and her grandfather was Sultan of Bengal, the huge province in northeast India that stretched from the foothills of the Himalayas to the Ganges delta. This connection was of great importance: Bengal, until well into the 19th century, used cowry shells for its currency, and the leading exporter of cowries in the Indian Ocean was the Maldives. In exchange for their cowries, the Maldives imported their staple food, Bengali rice.

The Maldivians farmed their cowries by floating branches of coconut palms in the sea, to which the shells attached themselves. Ibn Battuta described the next step: “They gather this animal in the sea and then put them in holes in the ground until the flesh rots, leaving the white shell…. They exchange [the shells] for rice with the people of Bengal, who also use them as currency. They also sell them to the people of Yemen, who ballast their ships with them instead of with sand. These cowries are also used in the lands of the blacks. I saw them being sold in Mali and Gawgaw at a rate of 1150 per dinar.”

In the Maldives, the exchange rate at that time was 400,000 cowries to the dinar, or more when the cowry was weak. This was 1/350 of the Malian rate, a proportion that gives an idea of the profits possible in the cowry trade if the shells could be transported far enough from their place of origin. And they were transported great distances: After Yemeni ships, Portuguese, Dutch and English ships also carried them as ballast, and huge quantities were auctioned to slavers in Amsterdam and London in the 18th century.

|

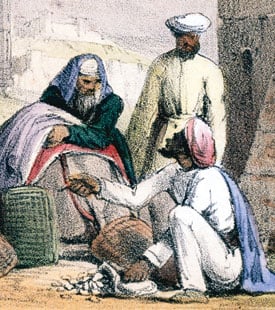

| A print from 1845 shows cowry shells being used as money by an Arab trader. BENJAMIN WATERHOUSE HAWKINS / SSPL / THE IMAGE WORKS |

The other essential product of the Maldives was coir, the fiber of the dried coconut husk. Cured in pits, beaten, spun and then twisted into cordage and ropes, coir’s salient quality is that it is resistant to saltwater. It stitched and rigged the ships that plied the Indian Ocean. Maldivian coir was exported to India, China, Yemen and the Gulf.

“It is stronger than hemp,” wrote Ibn Battuta, “and is used to sew together the planks of Indian and Yemeni boats, for this sea abounds in reefs, and if the planks were fastened with iron nails, they would break into pieces when the vessel hit a rock. The coir gives the boat greater elasticity, so that it doesn’t break up.”

The Maldives were the first landfall for traders sailing to India from the Arabian Gulf, South Arabia or the Red Sea. In the Maldives, ships could take on fresh water, fruit and the delicious, basket-smoked red flesh of the black bonito, a delicacy exported to India and China and Yemen. The people of the archipelago were gentle, civilized and hospitable. They produced brass utensils as well as fine cotton textiles, exported in the form of sarongs and turban lengths. These local industries must have depended on imported raw materials, although it is possible cotton was grown on some of the islands.

Although the archipelago produced not a single spice or exotic wood, nor any of the precious things commonly associated with the eastern trade, the inhabitants generated considerable wealth for themselves by developing their own resources. |

|

Historian and Arabist Paul Lunde studied at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies and specializes in Islamic history and literature. He is the author of Islam: Culture, Faith and History. With Caroline Stone, he has translated Mas‘udi’s Meadows of Gold and—forthcoming this fall from Penguin—Travellers From the Arab World to the Lands of the North, a collection of travel accounts. Lunde is a longtime contributor to this magazine, with some 60 articles to his credit over the past 33 years, including special multi-article sections on Arabic-language printing and the history of the Silk Roads, and the theme issue “The Middle East and the Age of Discovery” (M/J 92). He lives in Seville and Cambridge, England, and is working on an Internet project to map pre-modern Eurasian cultural and intellectual exchanges. He can be reached at paullunde@hotmail.com. |

< Previous Story | Next Story >