|

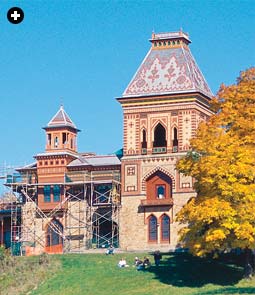

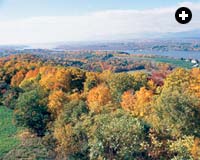

| Above: A portrait of Church by Charles Loring Elliot, painted in 1865, hangs in Olana. Below: Built on the 18-acre estate that Frederic Edwin Church purchased in 1860, Olana, in its original design, was based on a French manor. Today the house is a National Historic Landmark visited by some 150,000 people each year. |

|

n a hill overlooking New York’s Hudson River, and nearly in the shadow of the Catskill Mountains, stands Olana, a home built by one of the 19th century’s most celebrated American painters, Frederic Edwin Church. An orientalist confection in the eyes of many visitors today, Olana in fact traces its inspiration, design and furnishings back to Church’s three-month trip to the Levant in 1868. The resulting tug-of-war between Church’s careful observation and his personal artistic invention makes Olana an architectural landmark of Middle Eastern vernacular set in a New World landscape.

n a hill overlooking New York’s Hudson River, and nearly in the shadow of the Catskill Mountains, stands Olana, a home built by one of the 19th century’s most celebrated American painters, Frederic Edwin Church. An orientalist confection in the eyes of many visitors today, Olana in fact traces its inspiration, design and furnishings back to Church’s three-month trip to the Levant in 1868. The resulting tug-of-war between Church’s careful observation and his personal artistic invention makes Olana an architectural landmark of Middle Eastern vernacular set in a New World landscape.

The name “Olana” comes from Strabo’s Geography, in which the Greek historian named a fortified treasure house on the Araxes River that flows from Turkey into the Caspian Sea.

(Today the river is known as the Aras.) There is nothing in Church’s papers to suggest why he chose the name, but there is no doubt the place recreated a certain fantasy for both Church and his wife, Isabel. She wrote about a particularly sublime moment they had shared in the mountains of Lebanon: “We came upon an Arabian Nights looking house…. The most beautiful verdure surrounded the enchanted spot, …glimpses of the river and mountains one caught over and over.” She may as well have been describing Olana.

Church made the trip to Alexandria, Beirut, Damascus, Jerusalem, Petra and Baalbek—regretting having missed only the Giza pyramids—in the company of Isabel and their young son Frederic Jr. from December 1867 to February 1868. The voyage served as a getaway from the family’s grief over the deaths of the Churches’ two older children, and for him as an artist, it was an opportunity to go beyond his preoccupation with the American ethos of wilderness. Church had made his name and fortune in the 1850’s with such oversize paintings as “Niagara” and “Heart of the Andes,” which captured nature’s raw power so spectacularly that crowds paid admission to see them. Darwin’s theory of evolution had recently put into scientific words the feelings, as poet and art critic John Ashbery writes, of the “grander spectacle that inspired Church and his fellow artists in the halcyon days when nature could still be read as a message of hope set down in God’s cursive unfaltering hand.”

For a deeply religious man like Church, the Holy Land represented just the opposite of nature, a place of unchanging tradition and fixed belief. There, Church was struck by the stratigraphy of human existence: It was a place where the mark of human presence appeared everywhere. This newfound appreciation of the man-made landscape informed his subsequent paintings, which were often of classical ruins and other long-settled places. One of the greatest of these is of the “Treasury” at Petra, titled “El Khasne,” which still hangs over Olana’s sitting room fireplace—the only major work he never sold.

Before Church departed on his trip, he had commissioned the design of a French manor from a conventionally trained New York architect. But in the Middle East, he gained more than a philosophical appreciation for the antique: He also learned the more practical lessons of household esthetics, of how to create domestic comfort. Upon his return, he cancelled the manor and set about planning a house that would reflect his new thinking. The main wing of Olana was completed by 1872, and an attached studio was added in 1888.

|

Above: For Church and his wife, Isabel, Olana’s vistas of the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains recalled their views of the Barada River in Syria.

|

A careful reading of his wife’s trip diary and the popular Middle Eastern pattern books of the time helps a visitor to Olana see precisely how Church’s design choices were made and from where they came. For example, he chose some interior colors to evoke the ceiling of a specific Damascus home, while some masonry motifs he lifted from designs in his library’s books, which themselves were copied from known buildings.

Olana’s furnishings and carpets, seemingly thrown helter-skelter throughout the house, evoked his desert camps. “I for one was fascinated with tent life,” wrote his wife, probably echoing Church’s feelings as well. He plotted the curves of Olana’s carriageways so as to capture the same vistas of water and mountains he remembered seeing on the Barada River that flows through the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. That he should have sent home from Syria three white donkeys to pull a cart from which he could take in these views only confirms his eagerness to relive that experience every day.

|

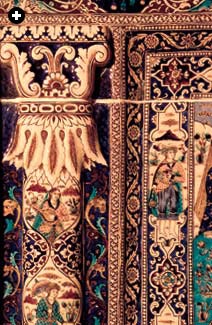

| Church designed Olana’s exteriors with an eye not only to decorative patterns, but also to the effects of sunlight on stone that had so profoundly impressed his painter’s esthetic. Of his visit to the Nabataean ruins of Petra, in Jordan, he wrote: “I never beheld anything so beautiful in rocks.” |

Church himself was overly modest in specifying the sources of Olana’s inspiration. In a letter to a friend, he wrote, “Having undertaken to get my architecture from Persia, where I have never been—nor any of my friends either—I am obliged to imagine Persian architecture—to embody it on paper.” Elsewhere he wrote, “I made it out of my own head.”

Church himself was overly modest in specifying the sources of Olana’s inspiration. In a letter to a friend, he wrote, “Having undertaken to get my architecture from Persia, where I have never been—nor any of my friends either—I am obliged to imagine Persian architecture—to embody it on paper.” Elsewhere he wrote, “I made it out of my own head.”

But Holly Edwards, curator of a recent exhibition on American orientalism at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, corrects such understatement, writing in the exhibit’s catalogue that “this modest description conveys Olana’s unique character but makes light of the voracious study and extensive travel that went into it…. A visit to this extraordinary house leaves little doubt that the real and imagined orient was the most important province in Church’s empire of the eye.” She called Church “the archetypal figure” among American orientalists because he found no artificial divisions among Middle Eastern-inspired painting, designing, collecting and decorating, all of which drew from a common well of pattern.

Church enlisted the technical help of Calvert Vaux, codesigner of New York City’s Central Park, to get his floor plans onto paper, but he himself took over the myriad designs for Olana’s painted wall stencils and polychrome masonry, architectural woodwork and even the decorative calligraphy—whose spelling he was able to check from a dictionary of Arabic and Persian in his library.

|

| Several of Church’s paintings still hang in Olana, where a pointed-arch window gives a view of the Hudson. |

Into Olana’s layout he translated the plan of a traditional Damascene house, with a central courtyard and radiating rooms. He added a Moorish arch spanning an exterior alcove leading to the front door. The entry hall, called the Court Hall, was adjoined by smaller rooms left and right and a grand staircase straight ahead, set on a broad, four-step dais.

“I have got new and excellent ideas about house building since I came abroad,” he had written from Beirut to a friend, then describing just such a floor plan. His plan for a dome on the Court Hall was not to be, however, so he chose to evoke the sky with a light blue ceiling paint instead.

In her diary, Isabel Church expressed her admiration for the concept of a hidden inner elegance entered through an unassuming portal. The interior of Damascus houses, she wrote, is “a great contrast to exterior…. Enter by a low narrow door, even I had to stoop, to go through, and thereafter passing through a small courtyard, find yourself in a large court paved with marble, white, mosaiced with colored marble, with fountains playing and flowers and orange and lemon trees making a pleasant shade and perfume, on one side a room entirely open with raised dais, divan, and decorated, then many other rooms [accessible] by smallish door on court.”

Olana’s rooms are stenciled in colors, some metallic and some pastel, that evoke both the reflectivity of mirrored ceilings in traditional rooms and the soft matte tones playing on the rocks at Petra that so impressed Church. “All the rooms have…mirrors on walls and ceiling,” wrote Isabel of Damascus, “highly and gorgeously decorated, and mirrors everywhere, amid the decorations little bits of mirror, and all woodwork inlaid with ivory and mother of pearl. At night by candlelight the effect must be quite splendid.”

Of the fine gradations of sunlight on sandstone, Church himself wrote in notes of his visit to Petra, “The tombs, many of them, were cut in a rich orange-red rock full of waving shades. Sometimes the rock was of a lovely dove tint also full of graded tints. I never beheld anything so beautiful in rocks.”

On February 25, at Petra’s “Treasury,” or khazna, Church wrote, “This wonderful temple is cut in the face of a tremendous precipice which is of a black color with an olive tinge in it. The rock when freshly exposed is of a beautiful reddish salmon color miscalled pink by some travelers. It is wonderful to see so lovely and luminous a color blazing out of black stern frightful rocks….”

|

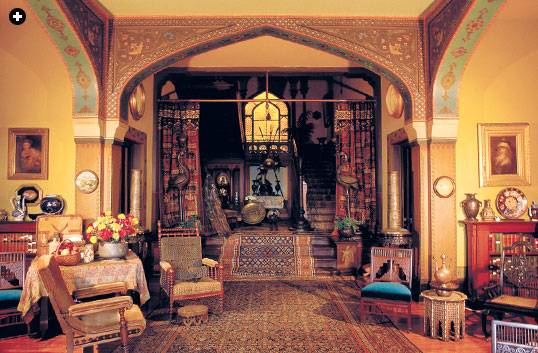

| In the Court Hall, the grandest of Olana’s rooms, Church drew the archway stencils based on Persian patterns from Isfahan’s Chehel Sutun (Forty Columns) pavilion and the Masjid-e Shah (Royal Mosque). He and Isabel furnished the room with “rugs, armour, stuffs, curiosities, etc. etc…old Turkish clothes, stones from a house in Damascus, Arab spears, beads from Jerusalem, stones from Petra, and 10,000 other things.” A

light blue ceiling evoked the sky. |

|

Surrounding two of Olana's fireplaces are painted tiles by Ali Muhammad al-Isfahani, a leading ceramic artist of Tehran and contemporary of Church.

|

The iterative color changes in Church’s sketches for the stencils that were later used at Olana—mauves, olives, salmons and, yes, dove tints—show just how painstakingly he worked to capture the mood of Petra’s stone on Olana’s walls. Six years after his travels, transforming this passage almost word-for-word into oil paint, he also completed the most important painting originating from this trip: a view of the khazna spied through the shadowy narrows of the siq, the rock passageway that leads to it. This is by far more personal than his other paintings, which include a panoramic “Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives” and a now-lost “Damascus from the Heights of Salihye.”

That Church should have so fully captured the details of the khazna’s façade is remarkable, given the rush he was in to sketch it. At all times afraid of bandits, he wrote of his working method, “I flung open my pocket sketchbook and drew the scene roughly, we then dashed down the path and seized another view, and so on, sketching and running until we reached the narrow plain below where the camels had long preceded us.”

When not “sketching and running,” he worked on camelback. “About twelve days of nodding on a camel ought to loosen a man’s spine into chronic politeness,” he wrote in a letter to a friend. The jagged lines in his sketch-filled Petra notebook, still in Olana’s collection, attest to this.

John Ashbery believes that Church felt that the coldness of northern light contradicted Olana’s warmhearted spirit and its origins under a desert sun, even though most artists prefer northern light to paint by. This, he writes, was likely the reason Church softened the light in his studio with amber-tinted glass and a latticed shade that resembles a mashrabiyyah, the turned-wood lattice panels whose varieties are common throughout the Middle East.

Pattern books of Middle Eastern motifs were also important sources for the expression of 19th-century Europeans’ and Americans’ taste for orientalism. Prisse d’Avennes’ L’Art Arabe d’apres les monuments du Kaire is perhaps the best known, but those by Jules Bourgoin (Les Arts Arabes, 1868), Pascal-Xavier Coste (Monuments modernes de la Perse, 1867) and Eugene Collinot (Les Ornements de la Perse, 1882) were of equal renown. The latter three were Church’s ready references.

The vase-and-tendril stencils on Olana’s interior doors and a six-pointed masonry star under a second-floor window were borrowed, via Bourgoin, from a Jerusalem church and an Alexandrine mosque, respectively. Illustrations from Coste, who was Ottoman governor Mehmet Ali Pasha’s architect in Egypt for 10 years, were the basis for the piazza’s columns. The Court Hall archway stencils were drawn from Isfahan’s Chehel Sutun (Pavilion of the Forty Columns), Masjid-e Shah (Royal Mosque) and Mader-e Sultan Islamic school. Tiled panels (zillij) in the brickwork above three windows are said to be patterned after motifs in the Alhambra.

At times, Church’s studied eclecticism went farther afield than the Middle East and the Islamic period. The mantelpieces and the studio wing balustrade were both designed by Church’s student Lakewood de Forest and executed at a woodcarving studio de Forest had established in Ahmedabad, India. The Court Hall stencils of winged Assyrian gods at the foot of the main stair originate in the pre-Islamic Near East.

Church was also the first American collector of neo-Safavid Persian tile work by the ceramist Ali Muhammad al-Isfahani, who was active in Tehran in the 1870’s and 1880’s. Two fireplace surrounds, signed by the artist, two figurative panels in relief and several vases by al-Isfahani were sent to Olana by W. L. Whipple, an American missionary friend of Church’s stationed in Tabriz. Whipple also provided Church with carpets, metalware and Persian paintings.

|

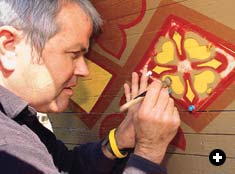

Restoration specialist Robert Hills applies a fresh coat of paint to a stenciled design. Today, Olana is maintaind by the New York State Historical Society. |

More than 2500 travel photographs were in Church’s collection, many bought or made in the Middle East. Among them were a picture of Church and his son on a camel, some 70 architectural images from the Palestine Exploration Fund and design studies from the Alhambra by Juan Laurent. Olana’s library also contained the standard orientalist literature of the time: Washington Irving’s life of the Prophet Muhammad, Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, Firdausi’s Shahnamah and Sir Richard Burton’s Arabian Nights, in addition to guidebooks and monographs on Persian art, Indian architecture and Arabian topography.

The most unmistakably Middle Eastern elements in the house are the Arabic calligraphy over the front door (which reads marhaba, “welcome”) and in the stenciled cartouches in the sitting room. Church was much taken with a verse in the Bible’s 39th Psalm—“While I was musing, the fire burned:…”—and he asked Whipple for an approximate translation into Arabic, which was then inscribed over the sitting-room fireplace.

Olana’s furnishings are a no less idiosyncratic meld of East and West. Church sent at least 15 crates of goods home from his trip, which he described as “rugs, armour, stuffs, curiosities, etc. etc…old Turkish clothes, stones from a house in Damascus, Arab spears, beads from Jerusalem, stones from Petra, and 10,000 other things.” Spears still lie about the Court Hall, and the studio’s curio cabinet still contains frankincense and stones Church collected at Petra.

The interior’s studied clutter was perhaps also inspired by the Churches’ visit to the Damascus home of Lady Jane Digby, who had scandalized Victorian values by marrying a Syrian and living independently. “Of somewhat disgraceful notoriety,” Isabel Church sniffed, but she found Lady Jane’s taste impeccable and inspiring nevertheless. “Her rooms were furnished semi-oriental, semi-European, forming a very agreeable and pretty coordination,” she wrote.

|

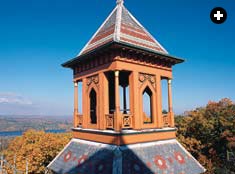

Olana's bright red cupola offers another view of the Hudson. The years before and after his Middle Eastern travels marked the pinnacle of Church's fame. In later years, his desire for travel waned — "with the exception of Syria," he wrote. He died in 1900. |

After returning from the Levant, Church lived another 30 years. He traveled in Mexico and painted throughout New York state, all the while watching his popularity and health slowly decline. Tastes in art were changing fast, with the Barbizon school leading the gradual extirpation of the large studio paintings typical of Church’s work.

With evident nostalgia, Church wrote in a letter to a friend, “With the exception of Syria, I think I will never desire ardently to revisit the Old World.”

Upon Church’s death in 1900, his son Louis took over Olana’s management. When Louis’s daughter-in-law died in 1965, Olana came within weeks of being sold at auction and its contents dispersed. Quick action by architectural preservationists saw that it was transferred intact to state ownership. Today it is a state historic site, open to the public under the trusteeship of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

Unlike other great orientalist homes in the United States—Longwood Plantation in Natchez, Mississippi (unfinished), P. T. Barnum’s “Iranistan” mansion in Bridgeport, Connecticut (burned), and Doris Duke’s fantastical Shangri La in Honolulu—Olana’s esthetic lineage reaches back to real sources and real places. With Isabel’s diary in one hand and Church’s Middle Eastern pattern books in the other, a visitor to their house today can almost follow their footsteps through the Levant and realize that, for them, it truly was a treasure house and, as Church called it, “the center of the world.”

www.olana.org

Exhibition: Treasures from Olana, www.treasuresfromolana.org

Saudi Aramco World thanks Olana Associate Curator Valerie Balint for her assistance in this article.