raise be to God, who has made the port of Jiddah the best of ports….” So wrote the Hijazi chronicler Ahmad ibn Faraj in his 16th-century history of his native city. Of more than a dozen ports that have served merchants, pilgrims and navies all along the 2300-kilometer (1400-mi) Red Sea route linking Asia and Europe, it is Jiddah that has best stood the test of time.

raise be to God, who has made the port of Jiddah the best of ports….” So wrote the Hijazi chronicler Ahmad ibn Faraj in his 16th-century history of his native city. Of more than a dozen ports that have served merchants, pilgrims and navies all along the 2300-kilometer (1400-mi) Red Sea route linking Asia and Europe, it is Jiddah that has best stood the test of time.

|

Jiddah is today the second-largest city in Saudi Arabia, and the busiest port. In 2004, it handled some 33 million tons of cargo, and one million passengers passed through it. Top: This engraving is based on a mid-19th-century sketch by a British naval captain. The mountains are slightly exaggerated. Note the fortifications at both left and right, as well as the desert encampments, far right. Until modern times, the loading and unloading of cargoes was still done using lightering craft. The Scottish explorer James Bruce summed up Jiddah’s advantages after his visit in 1769: “The port of Jiddah is a very extensive one, consisting of numberless shoals, small islands, and sunken rocks, with channels, however, between them, and deep water. You are very safe in Jiddah harbour, whatever wind blows, as there are numberless shoals, which prevent the water from ever being put into one general motion; and you may moor head and stern, with twenty anchors out if you please.”

PHOTO: KARIM SAHIB / AFP / GETTY IMAGES; ENGRAVING: NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM |

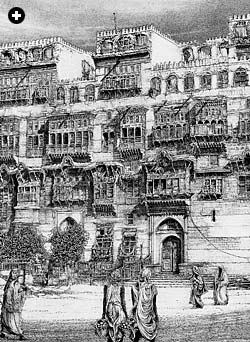

Jiddah’s city center still contains the multistoried houses of coral stone and plaster, adorned with teak doorways and latticework balconies, that typified the architecture in ports on both sides of the Red Sea until the last century. Some 400 to 500 buildings, dating from the 18th and 19th centuries—even some entire streets—testify to long-term investment and prosperity, a pattern that continues today in Saudi Arabia’s second-largest city and one of the largest modern container ports in the Middle East.

|

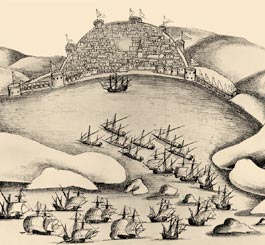

The earliest known depiction of Jiddah shows the unsuccessful Portuguese raid of 1517. They never reached Jiddah again.

GASPAR CORREA / LISBON GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY |

Ibn Faraj goes on to say that Jiddah is “attached to the Ka’bah,” and indeed the city was and is known throughout the Muslim world as the port of Makkah, which lies inland some 75 kilometers—48 miles, only a day and a night by camel. It is easy to take for granted that Jiddah’s economy depended on the pilgrimage to Makkah and the mercantile activity that came with it.

There is only limited truth in that view. Pilgrims did go in for a good deal of buying and exchange all along their routes and at Makkah itself, and rulers from Egypt to Muslim India often sent food subsidies and other gifts of pious patronage to the Holy Cities. Ship captains from India also sometimes combined their cargo-carrying with pilgrim traffic. However, the pilgrimage takes place only during one month of the year. Furthermore, the Islamic calendar is a lunar one, so the time of the pilgrimage advances by 11 days each solar year. (See "Patterns of Moon, Patterns of Sun") As a result, about half of the pilgrimages in any 33-year period fall outside the months of the northeast monsoon, which blows from October to March—and it was only during the latter part of that season that ships regularly sailed north into the Red Sea, in order to reduce their wait for the northerlies of early summer that could carry them home. These facts decouple the pilgrimage from the India trade, and they mean that historians must regard the two activities separately.

|

| JEAN BAPTISTE NICOLAS DENIS / NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM; EARTHSAT / DIGITAL GLOBE / GOOGLE EARTH |

|

|

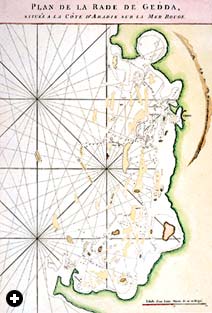

| Left: A 1775 chart of Jiddah harbor details soundings and the contours of the coastline. Above: A digital image from nearly 50 kilometers’ altitude (30 mi) shows both continuity and change along the coastline, as well as the vast, post-1980’s sprawl of Saudi Arabia’s second-largest city northward and inland from the original harbor. Near the top, King ‘Abd al-’Aziz International Airport is visible. |

|

Moreover, the vast majority of pilgrims traveled to the Holy Cities not by sea but overland, with the great caravans from Cairo, Istanbul, Damascus, Baghdad and southern Arabia. The general rule was that only pilgrims from sub-Saharan Africa, India and Malaysia arrived in Jiddah by boat.

Historical statistics are few, but travelers’ and officials’ reports indicate widely varying pilgrim numbers. One of the highest was 100,000, recorded in the year 1279. In 1383, some 17,000 pilgrims crossed Sinai in the Egyptian caravan, and in 1503 the Italian traveler di Varthema estimated about 40,000 in the Damascus caravan. In 1814, during the Ottoman campaign against the Al Sa‘ud, Jacob Burckhardt reported that only 500 pilgrims arrived from Africa via Sawakin (in today’s Sudan). In 1831, a British report estimated 120,000 pilgrims in total, about 20,000 of whom arrived at Jiddah by sea from India, Malaya, the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea ports of Suez, Qusair, Sawakin and elsewhere—and that seems to have been the best year for half a century or more. What is striking is how small overall pilgrim numbers were. They cannot have contributed a very great deal to the prosperity of Jiddah.

Things changed only with the introduction of steamships, which became common in the Red Sea after the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal. Although steam dealt a blow to the overland pilgrim routes, it proved a boon to the maritime ones: In 1893, 96,000 pilgrims were registered arriving in Jiddah by steamship, and figures of that scale were commonplace into the 1920’s. Change came again with international air travel: Today, some two million pilgrims pass annually through Jiddah’s King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz International Airport—80 percent of the total number.

|

|

| Driven by warming and cooling of the Asian landmass, monsoon winds blow seasonally throughout the Indian Ocean region, from the Red Sea in the west to the South China Sea in the east. In the Red Sea, the monsoon’s influence stops at 21 to 22 degrees north latitude—about where Jiddah lies. In the northern Red Sea, where the winds are unaffected by the monsoon, the wind is from the north year-round. The Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt wrote in 1814: “The fleets, principally from Calcutta, Surat and Bombay, reach Djidda in the beginning of May … The India fleets return in June or July.” |

o for the 1200 years before the arrival of steam, something more than Ibn Faraj’s reference to Makkah is needed to account for Jiddah’s prosperity and endurance as an entrepôt. That factor is the sea trade between India (and points east) and the Mediterranean. The English explorer and hydrographer James Wellsted, who surveyed the Hijaz coast in 1831, was struck by Jiddah’s supremacy in commerce. He listed the goods brought there from India: rice, sugar, fine muslin, cashmere shawls, other coarse and fine cloths, indigo, teak, coconut oil, coconuts, pepper, ginger, turmeric, other spices from the Far East and coffee from Yemen. The greater part of these goods, he reported, were purchased by the Jiddah merchants for transshipment to agents in Cairo, who in turn sold both locally and for export to the Mediterranean and Europe. In addition, wheat, tobacco, Persian rugs and dates were imported to Jiddah from Iraq and the Gulf for local consumption. Wellsted wrote:

o for the 1200 years before the arrival of steam, something more than Ibn Faraj’s reference to Makkah is needed to account for Jiddah’s prosperity and endurance as an entrepôt. That factor is the sea trade between India (and points east) and the Mediterranean. The English explorer and hydrographer James Wellsted, who surveyed the Hijaz coast in 1831, was struck by Jiddah’s supremacy in commerce. He listed the goods brought there from India: rice, sugar, fine muslin, cashmere shawls, other coarse and fine cloths, indigo, teak, coconut oil, coconuts, pepper, ginger, turmeric, other spices from the Far East and coffee from Yemen. The greater part of these goods, he reported, were purchased by the Jiddah merchants for transshipment to agents in Cairo, who in turn sold both locally and for export to the Mediterranean and Europe. In addition, wheat, tobacco, Persian rugs and dates were imported to Jiddah from Iraq and the Gulf for local consumption. Wellsted wrote:

Jiddah, from its critical situation, is well adapted as a commercial depôt for the productions of the upper and lower parts of the [Red] sea. Boats from Yemen, or the southern part of the sea, are not permitted to pass this port without entering to pay a heavy duty, the consequence of which is, that they prefer landing their cargoes there, a part of which being required for the Egyptian market, is re-shipped from thence in vessels belonging to the Jiddah merchants.

|

The view, taken in 1938, looks northwest over the old city. Still visible is the wall along the southern side, which stood until 1947.

COURTESY WILLIAM FACEY |

Before Wellsted, both the German explorer Carsten Niebuhr, in 1762, and the Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt, in 1814, had remarked on Jiddah’s pivotal role in the Red Sea trade. They both make it clear that Jiddah’s prosperity was based on its role as the exclusive Red Sea entrepôt between India and Egypt. According to Niebuhr, Jiddah was “no more than a mart between Egypt and India. The ships from Suez seldom proceed further [south] than this port; and those from India are not suffered to advance [north] to Suez.”

Burckhardt was equally emphatic: The fleets, principally from Calcutta, Surat and Bombay, reach Djidda in the beginning of May, when they find the merchants already prepared for them…. Large sums are also sent hither by the Cairo merchants to purchase goods on their account; but the cargoes for the greater part are bought up by the merchants of Djidda, who afterwards send them to Cairo to be sold for their own advantage. The India fleets return in June or July…. It is the nature of this commerce that renders Djidda so crowded during the stay of the fleet. People repair thither from every port on the Red Sea.

Their comments illuminate one of the central rules of Red Sea commerce, formalized by a pact between shipmasters and port authorities: Customs dues on the India–Egypt trade were to be paid at Jiddah. Over the centuries, control of Jiddah oscillated mostly between the Sharif of Makkah and governors appointed from Egypt; the latter would have run it as an Egyptian port with some split of revenues to local authorities to reflect the delicate, uneasy balance of power between Cairo and Makkah. Regardless of who was uppermost, however, it seems to have become compulsory for ships to call at Jiddah and declare themselves. In part, this reflected the political reality that control of Jiddah was key to the control of Islam’s two holy cities, Makkah and Madinah, and, from there, of the whole of the Hijaz. Thus favor shown toward Jiddah—whether, on the one hand, by the Sharifs of Makkah or, on the other, by the Ayyubid and Mamluk sultans of Egypt from the 12th to the 16th centuries and their Ottoman successors after 1517—reflects the desire to maintain a hold over the heartland of Islam.

|

Pilgrims debark from a steamer in the 1940's. Pilgrim traffic through Jiddah grew dramatically in the mid-19th century as steamships replaced the traditional overland caravan routes.

MAX STEINEKE / SAUDI ARAMCO |

Jiddah was founded sometime around AD 646, when the Caliph ‘Uthman decided that al-Shu‘aybah, to the north, should be abandoned because Jiddah offered a safer harbor. Jiddah’s role remained minor until the 10th century, when Fatimid-ruled Cairo eclipsed Abbasid Baghdad. The India trade followed the shift in regional power: The Arabian Gulf gradually ceased to be the main artery of commerce from the Indian Ocean into the Islamic lands and the Red Sea took its place. In response, some wealthy Persian merchant families abandoned Siraf, on the Gulf, and migrated to Jiddah, and from this point Jiddah begins to figure in historical accounts as a prosperous Red Sea port with a city wall and water cisterns.

During the centuries that followed, Jiddah seems to have experienced at least three periods of decline, generally attributable to misrule, but in the main its trajectory was upward. Both the celebrated Persian traveler Nasir-i Khusraw, in 1050, and Ibn Battuta, in 1330, found the city flourishing. Prosperity continued into the 15th century, driven by ever-growing demand in Renaissance Europe for luxury goods, the trade of which was controlled by the Mamluk rulers of Egypt and the Serene Republic of Venice.

With the Portuguese discovery in 1498 of the route into the Indian Ocean around the Cape of Good Hope, Jiddah took on a new strategic significance. The Mamluk rulers of Egypt were keenly aware of the threat to their control of the India trade that the Portuguese represented. It was vital to prevent the Portuguese from seizing Aden, because from there, they could control the Red Sea. Jiddah was reinforced, its wall rebuilt, and in 1517 the only Portuguese raid on Jiddah failed.

After 1517, when the Ottoman Turks took control of Egypt, the Hijaz and Yemen, they maintained the same vigilance; in 1538, a large Ottoman fleet sailed down the Red Sea and all the way to Gujarat in India, where it confronted the Portuguese. As a result, the Portuguese never managed to gain a foothold in the Red Sea. Ottoman security policy ensured that Egypt’s grip on Jiddah remained tight—a state of affairs that maintained the city’s economic prosperity while depriving it of political autonomy.

In 1700 a French doctor, Charles Jacques Poncet, visited Jiddah and observed that “there is great trading thither, for all the vessels which return from the Indies come to anchor there. The Grand Seignior [i.e., the Ottoman Sultan] does usually employ 30 great vessels in those seas for the transportation of merchandizes.”

The English traveler William Daniel, in the same year, is more detailed in his description of trade at Suez, which he says had:

about 40 sail of ships, who trade every year between that place and Judda; their outward merchandise being little or nothing but provisions and pieces of eight, and their return all sorts of spices, muslins, silks, precious stones, pearls and amber-grease, musk, coffee and many other druggs; which are brought by the trading vessels which come yearly from India to Mocha and Judda, and transported by land [from Suez] to Cairo and Alexandria.

By the time of Niebuhr’s visit in 1762, Britain had established the basis of its trading empire in India, and Jiddah was increasingly frequented by ships of the British East India Company, which had a “factory,” or depot, in the town. Whoever’s writ ran in Jiddah, and whatever rules applied, the port’s role in the India trade seems to have been a well-established feature, and the foundation of its commercial position.

iddah’s pivotal role in the India trade thus owed much to political factors. But a close look at records of Red Sea voyages reveals a deeper reason than politics for its commercial success: the wind pattern of the Red Sea.

iddah’s pivotal role in the India trade thus owed much to political factors. But a close look at records of Red Sea voyages reveals a deeper reason than politics for its commercial success: the wind pattern of the Red Sea.

It is quickly apparent from those records that the half of the Red Sea north of Jiddah presented a serious obstacle to sailing vessels. The great navigator Ahmad ibn Majid, who lived in the last decades of the 15th century, gave comprehensive sailing instructions in his navigation manuals for all the coasts of the western Indian Ocean, the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea. As a virtuoso long-distance navigator himself, Ibn Majid took pains to record everything he knew for his fellow practitioners in the India trade. How significant it is, then, that he covers the southern half of the Red Sea in detail, but the northernmost point that he describes is Jiddah. Oceangoing seamen of the India trade never went beyond Jiddah. Ibn Majid and his contemporaries were experts in the monsoon sailing regime, and he makes it clear by omission that the northern Red Sea fell outside it.

This is because in the northern half of the Red Sea above Jiddah, the prevailing wind blows from the north the whole year-round. Even in the southern half, the wind blows from the north for most of the year. It is only during a relatively short time between October and March or April that a southerly wind blows, and it blows reliably only as far north as the latitude of Jiddah and, on the African side, ‘Aydhab.

|

Today, about two million pilgrims from around the world pass annually through the Jiddah's King 'Abd al-'Aziz International Airport.

SAMIA EL-MOSLIMANY / SAUDI ARAMCO WORLD / PADIA |

That left sailing in the northern part of the Red Sea to smaller coasting vessels, which could take advantage of on- and offshore breezes at most times of the year, provided they were not in too much of a hurry. (Fleets of Ottoman galleys could, and did, make their way from Suez all the way down the Red Sea and back again, but galleys can be rowed.) One such voyage was recorded in 1541 by the Portuguese João de Castro, mathematician and future viceroy of the Indies, who conducted the first European scientific exploration of the Red Sea coast of Africa. It took him and his men 66 days to go from Massawa north to Suez, and they got there mostly by rowing into contrary breezes. Only twice did they get a day of sailing. On seeing the size of the Ottoman fleet at Suez (“41 ‘royal ships’ and five large vessels”) and the defenses, they decided that discretion was the better part of valor and they prepared to return south. On leaving Suez, de Castro sighs: “We were at death’s door in our ships from exhaustion.” By contrast, the return voyage to Massawa took them a mere 25 days.

|

In the early 20th century, some of Jiddah’s most ornate rawasheen, or bay windows with turned-wood screens, adorned “Bayt Baghdadi” (“Baghdad House”). Notable residents have included the Ottoman governor, Harry St. John Philby and, in the 1930’s, the offices of Standard Oil of California (SOCAL), the founding partner of what later became the Arabian American Oil Company, forerunner of today’s Saudi Aramco.

PETER FACEY (AFTER A PHOTOGRAPH BY FLOYD OHLIGER)

|

This natural fact of Red Sea winds is a constant in the history of those waters. It provides some explanation why, both far back in antiquity and in Islamic times, ports on the Egyptian side show a tendency to be some way down the coast and not at Suez, at the farthest north. Suez might look on the map as if it were in an obvious position geographically, but in navigational terms it was inaccessible. That is why we find, under the Ptolemies and Romans, Myos Hormos (Qusair) and Berenike (Ras Banas)—both quite a way down the African coast of the Red Sea—developed as ports and served by well-maintained land routes from the Nile Valley. Only with the coming of steam in the 19th century did the wind regime of the Red Sea become irrelevant to the location of ports, and it is only then that Suez rose to preeminence.

The Jiddah–‘Aydhab latitude—the northern limit of southerly winds—was thus always the limit of sail-powered direct trade bound for Alexandria or Cairo. But after Roman times, why did the major commercial port of the Red Sea develop on the Arabian, and not on the African or Egyptian, coast? Only the pilgrimage to Makkah explains that: Islam changed the pattern of the centuries-old India trade by making the Hijaz coast of the Red Sea a destination for the first time. And on the Hijaz coast, there was no better-placed port than Jiddah.

The beauty of Jiddah’s traditional Red Sea architecture is a living memorial not just of its unique role as the port of Makkah, but also of the central part it played in the sailing commerce between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean. The teak for the ornate filigree screens on the rawasheen balconies of Jiddah’s old houses symbolizes both the trade with India and the cooling breezes that once blew that trade to its harbor—and blew it no farther.

|

A publisher, historian and museum consultant, William Facey has studied the countries of the Arabian Peninsula for more than 30 years. His main focus has been Saudi Arabia, and he is the author of Riyadh: The Old City, Back to Earth: Adobe Building in Saudi Arabia and Saudi Arabia By the First Photographers. He is director of Arabian Publishing Ltd., London.

|

This article appeared on pages 10-16 of the November/December 2005 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

See Also: IBN MAJID, SHIHAB AL-DIN AHMAD IBN MAJID IBN MUHAMMAD AL-NAJDI, INDIAN OCEAN, SAUDI ARABIA- DESCRIPTION AND TRAVEL, SAUDI ARABIA- PORTS

Check the Public Affairs Digital Image Archive for November/December 2005 images.