ome and sit by the fire.” Fatima Yussif, my hostess, pushes a few small goats aside and points invitingly at a stool. Milk simmers in a pot above the flames. It will be breakfast for the several children who are still asleep in the large family bed in her tent.

ome and sit by the fire.” Fatima Yussif, my hostess, pushes a few small goats aside and points invitingly at a stool. Milk simmers in a pot above the flames. It will be breakfast for the several children who are still asleep in the large family bed in her tent.

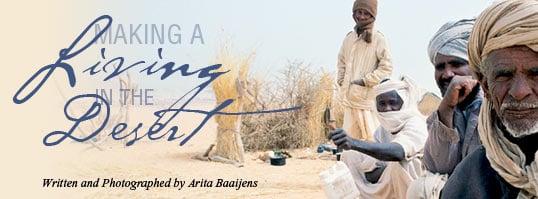

The wind blows relentlessly across the savannah. It is bitterly cold as the winter dawn shimmers through gray clouds of dust. The men, shepherds of the Shanabla tribe, return shivering from their nocturnal rambles. They wear thick overcoats with extra blankets wrapped around their shoulders. They guide the flocks along to their farig, or family camp, where I’ve become a temporary live- in relative. Fatima’s small tent is pitched next to that of her favorite son.

A nomad’s tent is almost always a woman’s property and responsibility. Usually it is richly adorned with colored cloth and plaited leather bags, but Fatima has furnished hers sparingly. There is a roll-up bed made of dried palm fronds, and next to it an utfa, a woman’s camel saddle, which is stuffed with leather bags and gourds. The wall behind the bed is covered with dark brown cowhides. There is a wooden trough, several stools and a few cooking utensils. That’s all.

Fatima runs the household mostly on her own. Her husband, Mohamed Nur, works in the camel market of El Obeid, the capital of Sudan’s Northern Kordofan province, about 40 kilometers (25 mi) northwest. During the great drought of 1984 and 1985, which affected some 4.5 million people from Chad to the Red Sea, the family lost much of its livestock, and Mohamed was forced to go to town to look for work. He ended up building a house there, marrying a second wife and starting a second family. Now, he visits the farig once a week.

Area: 2.5 million square kilometers (965,000 sq mi), 1/4 the size of the United States.

Estimated population (2004): 40 million

Estimated percentage of North Sudanese who are full-time pastoralists: 7 to 15

Estimated percentage who are part-time pastoralists: about 50

Estimated number of tribes in Sudan: 500

National population of camels: 3 million (world’'92s second largest, after Somalia)

Population of other livestock: 113 million

Percentage of livestock owned by nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralists: 90

Percentage of land that is arable: 5

Percentage that is “'93permanent pasture”: 46

Area of North Kordofan Province: 185,000 square kilometers (71,400 sq mi)

Major tribes of North Kordofan: Kababish, Hawawir, Kawahla and Shanabla are herders; Gawaama and Dar Hamid are agro-pastoralists; Bederia are farmers.

|

Among the nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes in northern Sudan, wives enjoy a great deal of freedom because the male head of the family spends much time away from home traveling with camels or, as Mohamed does, working in town to supplement the income the family gets from livestock. When the husband is absent, women run their lives independently, although they will often consult male relatives on important decisions. In terms of a woman’s workload, a husband’s presence does not make much difference: Fetching water and firewood, cleaning, looking after children and small animals, cooking, washing, mending clothes, weaving mats, selling milk and setting up and breaking down the tent are all women’s jobs. (See page 41.) Although family life without a husband’s consistent presence has disadvantages, it lightens a wife’s load in one respect: It means a greatly reduced stream of visitors for whom tea, coffee and meals must be prepared.

The bleak sun hovers above the treetops as Fatima’s daughter Aisha carries two jerry cans to the paved road. The plastic containers are filled with goat’s milk, and she will sell them to the wholesale buyer who passes by at eight every morning. He will sell the milk in the market in El Obeid. Other tribes frown on this practice because the custom of the region demands that milk be distributed free, not for profit.

Aisha and Fatima, however, have more basic issues to worry about. The Shanabla tribe (pronounced sha-NA-bla) is unique among the major tribes of North Kordofan because the Shanabla have no dar, or government- recognized homeland. As a result, the tribe leads an entirely nomadic existence. Until recently, this was easy because there were enough communal grazing grounds to accommodate the Shanabla’s camels, cattle, sheep and goats. Farmers, who are mainly from the Bederia and Gawaama tribes, were usually pleased when Shanabla arrived on their lands: After all, animal dung is excellent fertilizer, and it came free of charge.

But times have been changing. Since the 1970’s, government-supported, investment-driven agriculture has put vast areas of formerly pastoral land to the plow throughout the White Nile region. In the last decade, Sudan’s agricultural area has grown by about 30 percent, much of it on land that the Shanabla used during the dry season, from October to May. But without a dar, Shanabla have been powerless to check this encroachment on their resources. Now, many of their wells lie inaccessible on farmland that also often blocks traditional migration routes. As a result, the tribe has been forced to spend less time in more fertile regions and more in the drier lands, where grazing can be scarce and where long-term desert climate cycles have made droughts worse.

All of this means that Shanabla livestock have less to eat, and many Shanabla are struggling to maintain their subsistence livelihoods. Industrial-farm landowners are not generally among the farmers that host the Shanabla, and the small-time tribal farmers who remain are increasingly likely to object to the arrival of itinerant Shanabla.

This is exactly the situation at Fatima’s farig. After hearing about a neighboring farmer’s complaint that Shanabla sheep and camels had once again eaten into his harvest, Fatima’s brother Ibrahim, who has joined her by the fire, comments flatly, “Our animals have to eat.” To prevent trouble, Ibrahim says, he and his brothers have taken to letting their flock browse at night.

As we sit chatting around the fire, a farmer’s wife rides by on a donkey. As one of the family’s guard dogs begins to bark, she shouts, “This is our land! It would be better if that dog looked after your herd!”

Ibrahim sighs. “A farmer can stick his spade into the ground anywhere he wants,” he complains, “but nobody seems to care about the needs of nomads. It’s all one big headache. If he loses sight of his animals, even for the short- est time, he will be in trouble with a farmer.”

Ibrahim has a point: As untilled pastureland shrinks, crop damage by livestock is on the rise. If a farmer is not pleased with the compensation settlement he is then offered by a Shanabla shaykh, the farmer can take his case to court, where nomads have no say in the assessment of damages nor any right of appeal. As one Shanabla shaykh put it dryly, “Conflicts between herders and farmers are as old as Cain and Abel.”

Pastoralism in the Sudan is a centuries-old form of natural resource use and management. It entails varied types of movement, ranging from pure nomadism, typically characterized by camel breeding and long-distance, year-round movement, to periodic, seasonal (“transhumant”) movement over shorter distances. Some pastoralists are “agro-pastoralists,” which means that they combine seasonal farming with livestock-raising and

varying degrees of nomadism.

|

After the herdsmen have breakfast and a few hours’ sleep, it is time for the camels to graze. Ibrahim has grown-up sons who help him with these tasks. His younger boys take care of the sheep and goats. Girls do some of the domestic chores. “It’s a hard life,” both Ibrahim and Fatima agree, “but don’t forget that in the rainy season, our lives are a lot happier. During the wet summers there is grass everywhere. No trouble with angry farmers then!” they say cheerfully.

Omar Egemi is an assistant professor of geography at the University of Khartoum, and he is also employed by the United Nations Development Program (undp) to study ways to reduce resource-based conflicts between farmers and nomads. When he was young, his father was a Nile Valley trader who bartered with the Beja, a camel-herding tribe that lives in eastern Sudan and southeastern Egypt. As a child, Omar was fascinated by the Beja’s stories and lifestyle. Later, he traveled with them and wrote a master’s thesis about subsistence economics in the Red Sea hills. He confirms what Fatima and Ibrahim say. “Half of Sudan consists of land that is not suitable for agriculture. Only nomads know what to do with these areas. The fattest sheep and camels for the market are reared in marginal areas where no human being wants to live. The livestock sector annually contributes $140 million to the national economy. That is 23 percent of total [national] exports,” Egemi exclaims, adding that this income from the nomadic sector is second only to that of the oil sector.

But in spite of this statistic, Egemi asserts that scientists, development workers, policy makers and politicians have all tended to “favor agricultural development at the expense of pastoralism.” This, he says, leads to fewer people taking part in livestock raising, food insecurity among nomads, increased farmer–nomad conflicts and the concentration of livestock in fewer hands. Egemi can only shake his head at all this.

“Pastoral movement is an efficient adaptation to non-equilibrium ecologies,” he explains. “Mobility is the only way to rear animals in marginal areas on a sustainable basis.” In addition, it is essential to maintain—as the Shanabla and others do—a diversity of livestock, to split large units into smaller ones in times of drought and to use regional, non-hierarchical decision-making systems that respond efficiently to changing conditions.

Judiya is the Arabic word for the traditional means of reconciling tribal conflicts. It is based on mediation, forgiveness and agreement on fines, rewards and restitution. When there is resolution, it is then formalized with a recitation from the Qur’an.

Better than reconciliation, of course, is conflict prevention. Shanabla will often donate small goats and firewood to farmers, and they will also buy sesame oil, soap and grain from them. Most significantly, they will intermarry with farmers. And for any Shanabla festivity, farmers in the area are always invited. Many farmers are among the guests at a marriage celebration taking place in the Shanabla camp of Shaykh Abdel Bagi, a prominent livestock trader. For him, good relations with the people on whose land he and his clan are staying is a matter of good business.

In North Kordofan, 70 percent of the soil is sandy and supports only annual grasses and acacia trees. The other 30 percent, found in the central and southern districts of the province, is clay and heavy clay, which supports a richer cover of vegetation. Most of the nomads’ wet-season grazing areas are located in these regions.

North Kordofan is a dry zone. Rainfall varies from none at all in the far north to little in the southern savannah. Droughts occur every four to five years, and severe, multi-year droughts take place about once a decade. This complex ecosystem is well suited to pastoralists, who follow the rains with their herds. Scouts select sites with good grazing, and the poorer sites are left to regenerate.

|

“Is the meat ready yet?” Abdel Bagi rushes into the rakuba, a hut used as kitchen, that belongs to the groom’s mother, Bakheita Hamid. The rakuba is jammed with women stooped over the fires on which large pans of camel meat and onions in gravy are simmering. Abdel Bagi tastes it. “Very good,” he declares. He has a reputation at stake: His guests must be completely satisfied.

The groom’s friends arrive, sweeping through the farig on racing camels. Clouds of dust rise everywhere, whips crack, and women turn to shout encouragement. “It will be our turn later,” a girl says with a smile. She is busy adorning her braids with shining beads. In the afternoon, her golden jewelry and headdress will shine during the dance party for the young.

Later, when the celebration is in full swing, a colorful caravan of camels passes the camp—Shanabla enroute from one place to another. “This is how we arrived here, one week ago,” says Bakheita, pointing her wooden spoon at the tall utfas hung with pieces of flapping cloth that protect mothers and children against sun and wind. Beds, stools, sticks and canvas all sway to the rhythm of the baggage camels. Bright-eyed, the women in the rakuba watch the grand procession disappear. The horizon beckons.

nlike the Shanabla, the Kababish (pronounced ka-ba-beesh) are the tribe with the largest dar in all of Sudan. At the beginning of the 20th century, their paramount chief and modern founder, nazir Ali Al Tum, with British assistance, allied several tribes into a confederation that took on the name Kababish, and under his leadership the Kababish lay claim to most of the vast territory between the Nile and Darfur—much of modern North Kordofan province, an area approximately the size of North Dakota or Syria.

nlike the Shanabla, the Kababish (pronounced ka-ba-beesh) are the tribe with the largest dar in all of Sudan. At the beginning of the 20th century, their paramount chief and modern founder, nazir Ali Al Tum, with British assistance, allied several tribes into a confederation that took on the name Kababish, and under his leadership the Kababish lay claim to most of the vast territory between the Nile and Darfur—much of modern North Kordofan province, an area approximately the size of North Dakota or Syria.

“That was a phone call from Saudi Arabia.” Nazir Al Tum Hassan puts his satellite phone back on the dashboard of his Toyota Land Cruiser. It’s very late at night, and he is driving to his headquarters in Umm Sunta, 360 kilometers (220 mi) northwest of El Obeid.

“I would not be able to do this work without a car,” he says, explaining that he is constantly driving to meetings and conflict-resolution sessions to administer the affairs of the tribe’s estimated 70,000 members. He says he sees too little of his immediate family, but such are the burdens of a nazir, a near-royal title he has held for 15 years.

“We’re home.” The nazir is tired. He steers his car onto the hosh, the courtyard, where growling dogs jump on the vehicle. “As long as you stay close to me, they will not hurt you,” he grins.

I first met the leader of the Kababish several years ago in El Obeid, at the home of his cousin Nahid Fadlallah. Everybody rose when Al Tum Hassan entered. They remained silent when he spoke. A few weeks later, we met again in the Kababish capital of Hamrat Al Shaikh, a four-hour drive east of Umm Sunta. Again, everyone bowed deeply before him.

Now at home, he wants only peace and quiet. His shoes are off, the turban leaves his head, and he lets out a sigh of relief as he drops heavily onto one of the beds along the walls of the richly decorated tent.

“Make yourself at home,” he chokes as his two little daughters smother him playfully. His teenage son Hassan has more interest in the machine gun the guards bring inside than in his father’s return. Fatma, his 40-year-old wife, looks at the family scene and smiles. Self-confident, she addresses her husband with a tone of friendship and partnership. Both were raised in the ruling family of the Kababish, and both studied at Omdurman University.

“You met my eldest daughters in El Obeid?” Fatma asks me the next day, incredulous. She looks up from a large pot where mutton is simmering. I reply that I met the two students when I visited Fatma’s sister, who lives with her family near the university. In fact, the house was full of nephews and nieces—and all were at the university. There were boys who would have much preferred to go traveling with the camels, but in the nazir families, university study is now an obligatory part of growing up.

Al Tum Hassan’s mother clacks her tongue. “When I was young, studying was unthinkable for girls. Not that my childhood was boring.” Then, she says, the ruling family traveled throughout the land, living in tents, and she believes she saw far more of the country than do the nazir family girls growing up in Umm Sunta today.

For Al Tum’s family, the nomadic life ended when the need for education increased with the burden of administration. The lives of the other Kababish families have changed as well: In the thorny acacia forest of Umm Sunta stand several thousand permanent dwellings built of wood and sturdy white tenting cloth. All belong to sedentarized families who have moved from camel and sheep herding to vegetable farming, truck driving and wage labor on mechanized farms.

“Almost all Kababish lost their cattle in the catastrophic drought of 1984 and 1985,” explains Hassan’s cousin, Salim Musa Ali Al Tum. Then, he says, he watched destitute nomads leaving for the cities in search of food and work. Many invested whatever money they were able to save in new livestock, and a large number of families returned to the rural areas. But not all women, he says, were prepared to carry on where they had left off. Many preferred to stay with the children in the summer camps near the cities, where there were wells, a school and a small hospital. It’s the elder boys and the men, who look after the sheep and the camels, who enjoy roaming the land and who pushed for return to nomadic life after the drought.

Salim Musa says thoughtfully, “It is a good development that children are going to school. But as a result, a lot of nomad knowledge is lost. The teachers do not teach anything about plants, trees, animals, wells and grazing areas.” He says he would love to accompany me on the next leg of my travels among the tribes, but he is a government official now, he says, and he also has family obligations.

Women—Daily: Morning milking; making tea, cooking breakfast and feeding family members; cleaning; collecting water and wood; marketing milk; making cheese and butter; evening milking; cooking supper and feeding family members; handicrafts. Occasional: Nursing young animals; making or preparing mats and poles, pegs and ropes for tent. Women—Daily: Morning milking; making tea, cooking breakfast and feeding family members; cleaning; collecting water and wood; marketing milk; making cheese and butter; evening milking; cooking supper and feeding family members; handicrafts. Occasional: Nursing young animals; making or preparing mats and poles, pegs and ropes for tent.

Men—Daily: Morning milking; herding and rearing livestock. Occasional: Marketing livestock; wage labor in towns or abroad.

Children—Daily: Herding and rearing small livestock.

Source: Study of Pastoralists Seasonal Settlement Areas at Sheikan and Um Rawaba Localities. 2002, The Reduction of Natural Resources-Based Conflicts Among Pastoralists and Farmers Project, North Kordofan, SOS Sahel International UK.

|

But Juma Sineen says he will go with me. Juma is one of those Kababish who never fully recovered from the 1984–1985 drought. He lost all his animals and moved to El Obeid, where he found work as a guard. As soon as he had assembled another herd of sheep and goats, he left for Umm Sunta, where he still lives with his wife and two of his children. His eldest daughter has married and lives in Debba, near the Nile. One of his sons works as a driver in Omdurman, and every now and then sends some money back to the family. Juma no longer owns camels, but he has not forgotten how to put on a saddle. We agree to go into the dry northern and western part of the Kababish dar. We attach our bags of provisions and water cans to the saddle pommels: Time to leave.

“This reminds me of old times,” Juma beams as we leave Umm Sunta. He is more than 70 years old, and he speaks nostalgically about his past. Before the drought, he used to accompany young Al Tum Hassan as the nazir made his annual inspection round. Now, as then, Juma has his Kalashnikov handy: In this country, no one travels unarmed, mostly as a precaution against bandits.

Our first destination is Shaykh Hamid’s camp, near the border of North Kordofan and Darfur, the far western province where war has taken tens of thousands of lives in the past two years. I met Shaykh Hamid four years ago, and I am looking forward to seeing him again. We follow a dry river bed, where acacia trees and baobabs abound.

“Agul. Markh. Kitir. Sayal.” Effortlessly, Juma lists the names of the grasses, plants and shrubs we pass. His intimate knowledge of vegetation means survival for a herdsman. One grass has higher nutritional value; another is poisonous; still others provide essential minerals for the digestive systems of camels and sheep.

Along the way, Shaykh Fadlallah Salih Mohamed Al Tum and his guard join us. The month is January, when the tulba, or “herd tax,” is collected for the government by the nazir’s representative. Fadlallah knows all the families in the area, and he knows approximately how large their herds are. Although this is information a nomad will never volunteer, Fadlallah knows that wells are ideal places to estimate the sizes of herds.

The shaykh is certainly not universally welcome at this time of year, but you would never suspect that from the receptions we receive. “Welcome, welcome,” we hear everywhere we go. Unfailingly, by the time we have unloaded our camels, our host has already made a fire and brought tea; later, he will slaughter a goat. I find the jubilant hospitality difficult to accept, for a goat has considerable value. But refusing the gift is inconceivable in a land where a man is judged by his generosity to guests.

(March to June) Saif: Hot and dry—Families stay in camps with permanent water wells.

(June): Early rains—Young men move with the herd according to rains.

(July to October) Kharif: Cool and rainy—Families join the herders and follow the rains.

(November to February) Shita: Cold and dry—Depending on grazing, families may remain together or split into smaller units. Kababish men take camels to the winter grazing areas on the waterless sand plains in the far north (gizzu), while most families stay behind near seasonal water wells. Shanabla stay in the southern regions of North Kordofan and move camp every six weeks or so, depending on the hospitality—or lack of hospitality—of local farmers.

|

In Shaykh Hamid’s farig, it turned out he had been informed days ago about our impending arrival. He greets us with a warm embrace and quickly takes us to where a large white tent shelters us from the biting wind. Our stiff hands and faces warm up in the bright winter sun, and hot tea takes care of the rest.

In the evening, Hamid and his wife announce that I will sleep inside their house, for “it is too cold outside.” The tent is surprisingly warm and bright. Large discarded shawls cover the ceiling. Bags of grain and salt have been stowed behind pieces of canvas. Tooled and decorated leather storage bags adorn the walls. There is a fire burning in an iron basin, and the youngest grandchild gently sways in a hammock-like cot above the bed. She is crying. Her grandfather puts the little one on his lap and comforts her until she is asleep again.

In the days that follow, days are spent with the neighbors and relatives constantly drifting in and out for chats, and evenings are for the entertainment of gossip and stories around the fire. This easygoing family life is in stark contrast to the tension in which the Shanabla live. These Kababish do not depend on a farmers’ charity, for their dar is immense, and, in addition, this part of it is too remote and insufficiently arable to attract the eyes of even the irrigated-agriculture developers. Here, the nomads can still go where they please.

From Shaykh Hamid’s farig I spend several more weeks traveling through the desert in the company of Juma, and we encounter enormous diversity. We meet nomads who have become farmers. We meet families who make long journeys with hundreds of camels. Sometimes we find a woman at home alone, out in the middle of nowhere, because her husband is working in Libya. There are days we travel entirely alone. Sometimes we share a meal with a lone herdsman who looks after his sheep, or we drink tea with camel drivers who transport cut slabs of salt. And every now and then we come across nomads who have started a little shop and have placed the camels in the care of relatives. All of this makes it almost impossible to describe what Salim Musa calls “real nomad life.”

“Don’t bother!” smiles anthropologist Salah el Shazali of the University of Khartoum. “A nomad fits no label. He has too many roles. The key word is flexibility. It all depends on circumstances whether a herdsman will look for work in town or abroad, or become a farmer and subcontract his herd. Nomads minimize their risks by spreading them out, and the possibilities of doing this are endless.

“Nomad life is under pressure,” he adds, “but it will not disappear from Sudan.” Like Egemi, he points out the contribution of livestock-raising to the economy. “This is one solid support pillar for the future. The other is the age-old ability of the nomads to adapt.”

As far as the nomads themselves are concerned, there is not even a hint of hesitation when I ask elderly Juma what he would do with a million dollars.

“Buy camels and start again,” he says.

|

Arita Baaijens (www.arita.baaijens.com) lives in Amsterdam, where she is a writer and photographer and a former environmental biologist. For the past 15 years, she has trekked each winter through the Egyptian and Sudanese deserts with her camels. Photo by Erik Buis.

|