|

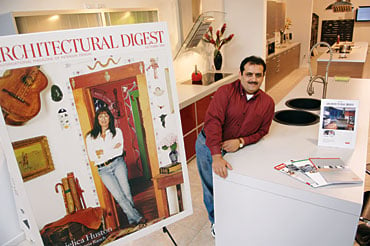

Loay is pursuing a dream: sleek kitchens. He recently left a position as assistant vice presi-dent of Compass Bank to open his own high-end kitchen design center. Jocular and easygoing, Loay has the promotional zeal of a new business owner, mixed with the incredulity of a kid who has been handed the keys to his own candy store. A native of Iraq, Loay emigrated to Canada in 1983, and then moved to Birmingham one year later to attend school. “Why Alabama?” He shrugs with his easygoing smile. “I applied to 20 to 30 colleges. I got accepted to Alabama.” He is married, and has two children, ages nine and 10.

I was a banker, a systems analyst, for 15 years. Four years ago, when I was building my first house and I wanted a slick, European-style kitchen, I had to go to Atlanta because we couldn’t find what I was looking for in Birmingham. The idea crossed my mind—why don’t we have something here? We’re a big city; a lot of people want this, with a lot of downtown buildings being converted into lofts.

I was going to do it as an investment. Then I decided to quit my job and do it full-time. People ask me, you’re doing what now!? Because they’ve always known me as a computer banking person working with numbers.

I’d always had a dream of having my own business, set my own hours. Now we’re open 10 to four. That’s a big difference. And sometimes if I feel like it, I go home during the day. [Laughs.]

You gain more freedom, more control over your time, your destiny. I thought, if it doesn’t work out, I’ll go back to the bank and be an employee again.

It was a big career change. I have a master’s in business, but I have so many different certificates. A lot of people put them all on the wall, but if I’d put mine, the whole wall would be full and be ugly. Now they’re all in a cheap folder.

I’ve always enjoyed designing since I was a little boy—Legos, I was addicted to it. In the old country, in Iraq, they offer vocational classes in the summer time. I did wood lathe creation, electrical wiring. These are the only diplomas I have framed. I designed my second house that I just moved into.

When we design a kitchen, we first consult with a client, work with them from A to Z to customize and personalize it to fit their lifestyle, from the height of the cabinets to everything else they need. The cooktop, we do it lower, so you can see what’s inside the pots and pans. We have a lot of pullout drawers. I like to have everything behind closed doors, have it very slick and clean, but also very functional and elegant. So if I want something, I have very easy access to it. I’m a big-time cook. I always have gatherings in my house—it’s part of life. We have a few Iraqis here; we get together and cook. Have Arabic food, speak Arabic. Very loud, of course. [Laughs.] I miss [Iraq].

People in Alabama haven’t seen this. People in Alabama aren’t like the people in Atlanta or Houston, who travel a lot. Some come in here and ask, “What is this, laminate?” Because they think a kitchen has to be oak, wood, stained. They come in and see a red kitchen, and they say, what is this?! But another group knows about this design. When they come in here, they say they love this. There was a woman architect. She called and said, “You’re kidding, where are you?! I’ve been wanting to find something like this. I’ll be there in 30 minutes!” |