|

Written by Frank L. Holt

Illustrated by Norman MacDonald

|

|

| In his article “Stealing Zeus’s Thunder,” published in the May/June 2005 issue of Saudi Aramco World, historian Frank L. Holt reported that a fresh discovery might add another chapter to the story of Alexander the Great and his elephant medallions—and indeed, it has—THE EDITORS. Here is his account of the new evidence. |

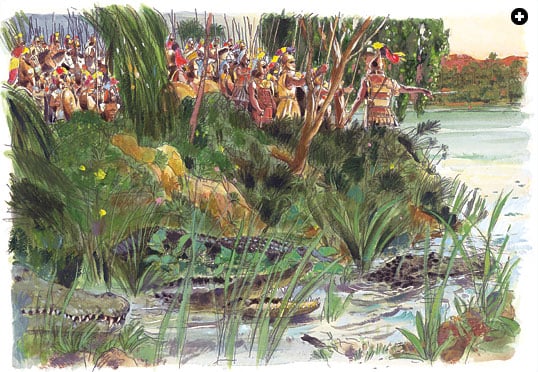

ne afternoon in 320 BC, a bask of crocodiles bloodied the Nile with the gore of a calamitous feast. More than 2000 men perished, far from the homes they had left behind many years before to conquer the world with Alexander the Great. Those veterans had survived epic battles, blizzards, disease and deprivation. More than once they had crossed the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates, Oxus and Indus Rivers on their way to the end of the world and back. They had outlived as many as six Macedonian kings, including Alexander himself, who had died in Babylon three years earlier.

ne afternoon in 320 BC, a bask of crocodiles bloodied the Nile with the gore of a calamitous feast. More than 2000 men perished, far from the homes they had left behind many years before to conquer the world with Alexander the Great. Those veterans had survived epic battles, blizzards, disease and deprivation. More than once they had crossed the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates, Oxus and Indus Rivers on their way to the end of the world and back. They had outlived as many as six Macedonian kings, including Alexander himself, who had died in Babylon three years earlier.

It was the demise of Alexander at that time and place that delivered these hapless victims to the waiting jaws of patient crocodiles. First, Alexander died without a competent heir, which prompted his grasping generals to fight for all or parts of his realm. Among the contenders were Alexander’s close friends Perdiccas and Ptolemy. The latter based his hopes on building an independent state in Egypt; the former (to whom Alexander had allegedly entrusted his signet ring) aimed to rule the whole empire. In the wars that followed, some of the conqueror’s old soldiers served Ptolemy, while others sided with Perdiccas.

It was the demise of Alexander at that time and place that delivered these hapless victims to the waiting jaws of patient crocodiles. First, Alexander died without a competent heir, which prompted his grasping generals to fight for all or parts of his realm. Among the contenders were Alexander’s close friends Perdiccas and Ptolemy. The latter based his hopes on building an independent state in Egypt; the former (to whom Alexander had allegedly entrusted his signet ring) aimed to rule the whole empire. In the wars that followed, some of the conqueror’s old soldiers served Ptolemy, while others sided with Perdiccas.

Thousands of the soldiers loyal to Perdiccas would eventually wade into the Nile and never walk out. They did so because of the second contingency of Alexander’s death: The king was to be mummified and ceremoniously transported from Babylon to a burial place in Macedonia, all under the direction of Perdiccas. In a daring act of piracy, however, Ptolemy stole his friend’s body and carried it off to Memphis in Egypt. This hijacking was more than just grand political theater: possession of Alexander was nine-tenths of the law in the competition for legitimacy, and Ptolemy had lofty plans for Alexander’s remains. Perdiccas therefore responded in force, leading into Egypt the luckless force that became a crocodilian repast.

In Alexander’s last great battle, he had crossed the Hydaspes River in India by outmaneuvering the forces of Rajah Porus. Now, the clash between Ptolemy and Perdiccas would also be decided by a cat-and-mouse game along the banks of a major river. As Ptolemy strengthened the defenses along his side of the Nile, Perdiccas on the opposite embankment probed for a weakness that would allow his army to cross. After failing near Pelusium, on the far eastern edge of the Nile Delta, Perdiccas tried to slip his troops across the river at the so-called Fort of Camels. Ptolemy was caught off- guard by this nighttime flanking maneuver, but rallied his men and reached the fort in time to save it. Perdiccas sent across successive waves of attackers, led by his corps of Indian elephants, but Ptolemy repulsed the pachyderms with Alexander-like élan, personally blinding the lead beast with a long spear and wounding its mahout. As the attackers faltered, Ptolemy fought conspicuously and inspired his Macedonian veterans to drive Perdiccas back across the river to the eastern bank. The demoralized invaders realized too late that Perdiccas at the Nile would not be able to emulate Alexander at the Hydaspes.

Still, Perdiccas convinced many of the survivors to make another night march upstream where they might sneak across the Nile above the Delta, near Memphis. This time it was nature, not Ptolemy, that crushed Perdiccas’s dreams.

As the first of his weary troops forded the river, the water came up to their chins, and a strong current tugged at their legs. Perdiccas therefore posted a line of elephants to their left in order to break the Nile’s flow. A corresponding file of cavalry waited to their right, downstream, to catch any man swept off his feet. All went well until, without any warning, the river inexplicably rose and desperate soldiers began to drown. The safety net of cavalry was insufficient to rescue the perishing, and soon crocodiles were seen gorging themselves on the weakest swimmers. A thousand men were killed by the beasts, and as many more were devoured after they drowned. The debacle shocked even the most callous veterans of a violent age of conquest. Alexander’s signet ring could no longer save poor Perdiccas, whose remaining troops stabbed him to death within hours of the catastrophe. The course of history had been decided in Ptolemy’s favor by a river and its dreaded carnivores.

With his victory clear, Ptolemy gave the vanquished invaders as much aid as possible, and he allowed the stunned survivors to leave Egypt at their leisure. What remained of the dead was gathered and solemnly cremated, and Ptolemy shipped the bones of the victims back to their grieving families in Macedonia. Enjoying great acclaim for his good fortune and generous spirit, Ptolemy’s reputation soared.

n the first years following Alexander’s death, Ptolemy (like the other so-called Successors) continued to mint the traditional coinage that had been issued by his hero. The main type of coin had shown Alexander’s putative ancestor Herakles (Hercules) wearing on his head the lion scalp that commemorated one of his legendary labors. It was, after all, normal Greek practice to reserve the “heads” side of a coin for the portrait of just such a god or goddess: Athena at Athens, Persephone at Syracuse, Helios at Rhodes and so forth. Then Ptolemy dared take a step that has stirred no end of debate among scholars—one that, in essence, threw a rock into the still waters of Greek art and religion, sending great ripples outward through time and place to Sicily, Syria, Rome and beyond: Ptolemy replaced the portrait of Herakles

on Alexander’s posthumous coinage with a stunning image of another god—Alexander himself.

n the first years following Alexander’s death, Ptolemy (like the other so-called Successors) continued to mint the traditional coinage that had been issued by his hero. The main type of coin had shown Alexander’s putative ancestor Herakles (Hercules) wearing on his head the lion scalp that commemorated one of his legendary labors. It was, after all, normal Greek practice to reserve the “heads” side of a coin for the portrait of just such a god or goddess: Athena at Athens, Persephone at Syracuse, Helios at Rhodes and so forth. Then Ptolemy dared take a step that has stirred no end of debate among scholars—one that, in essence, threw a rock into the still waters of Greek art and religion, sending great ripples outward through time and place to Sicily, Syria, Rome and beyond: Ptolemy replaced the portrait of Herakles

on Alexander’s posthumous coinage with a stunning image of another god—Alexander himself.

On these new coins, Alexander wears the scalp of an Indian elephant in the same way Herakles wore the lion pelt. Alexander also sports the aegis of Zeus, a scaly bib that could create thunder and ward off enemies. The aegis appears around Alexander’s neck, tied in place by the knotted bodies of two writhing snakes. In addition, these coins show above Alexander’s ear the unmistakable ram’s horn of the Egyptian deity Ammon (identified as Zeus by the Greeks). It was a conspicuous case of identity theft, as Ptolemy appropriated for Alexander the singular characteristics of the Graeco-Egyptian god. Ptolemy’s Alexander is Zeus/Ammon.

According to experts, Ptolemy thus not only exalted his hero but, by doing so, also elevated his own status as the caretaker of that hero’s corpse—now not just the body of a great leader, but of a god. A legitimizing cult of Alexander could thereby be established at Memphis and later moved to Alexandria, along with the mummy itself. In the reflected glory of the conqueror, Ptolemy could found the independent Egyptian state that he yearned to rule as king.

Ptolemy’s portrait of Alexander deified proved to be so potent that rivals such as Lysimachus in Thrace and Seleucus in Syria soon imitated its main features: ram’s horn, aegis and elephant scalp. Only the popularity of the elephant head-dress has puzzled scholars, since it had no obvious connection to the iconography of Zeus/Ammon. Why Ptolemy dressed Alexander in this fashion, calling attention to India rather than Egypt, has remained a mystery until a recent dazzling discovery from Afghanistan yielded up a single artifact that changes all of our assumptions about Ptolemy’s famous Alexander portrait.

|

| Ptolemy’s coin showed Alexander as Zeus, with the ram’s horn of Amon curving subtly above his ear. Scholars have wondered why Ptolemy showed him with an elephant scalp rather than the traditional lion scalp of earlier coins depicting Herakles. |

Imagine for a moment a treasure chest groaning under the weight of a thousand pounds of jewels, silver goblets, gold statuettes and the rarest of royal coins. Now picture a stash of nine such coffers—not merely a king’s ransom, but a whole dynasty’s—all rising from watery depths to sparkle in daylight for the first time in centuries. These are neither the spoils of Spanish galleons nor the sunken trove of a lost Sindbad. They are the equivalent mass of a single hoard hauled from a nondescript Afghan well in 1992. (See The Marvels of Mir Zakah, page 7.] Among its massive contents lay a lump of gold no larger than a humble us penny. Out of tons of treasure, it weighs less than an ounce, and yet it tips the balance of history in a new way.

On one side of the coin-like artifact can be seen a beautiful rendition of the same portrait that Ptolemy put on his money: Alexander gazes upward with large expressive eyes and pursed lips, his head covered in the scalp of an elephant. The aegis drapes around his neck, and the ram’s horn curls from his temple. A hint of Alexander’s wild mane manages to escape the edges of the headdress, while several longer strands drift down around his ear. A beaded circle frames the image. This portrait is a masterpiece, a treasure one might easily attribute to the same workshops in Egypt that produced the coins of Ptolemy. But turn the artifact over—and nothing less than an elephant stands in the way of any such attribution.

The Indian elephant appearing on the reverse, along with the same set of distinctive Greek monograms, identify this as a unique new variety of elephant medallion issued by Alexander himself to commemorate his campaigns in India. (The silver specimens of this series tell the story of the battle against Rajah Porus along the banks of the Hydaspes River in 326 BC, as reported in “Stealing Zeus’s Thunder.”) On each medallion, an Indian elephant provides the subtext for the numismatic narrative, and on one small variety, the pose of the pachyderm closely resembles that on the Mir Zakah gold artifact. The other sides of each silver piece feature, in sequence, the main Indian units overcome by Alexander’s army: the four-horse chariots and the native archers with their huge, powerful bows. Finally, on the large silver medallions, the desperate flight of Porus on one side is capped on the other by the compelling image of Alexander being crowned victorious by the goddess Nike. In Alexander’s right hand rests a thunderbolt, the divine weapon of Zeus, symbolizing the supernatural power wielded that day by Alexander. Since monsoon storms played a pivotal role in the defeat of Porus’s chariots and archers, Alexander takes full credit for them on these medallions.

|

| The Mir Zakah coin, believed to be the only lifetime portrait of Alexander the Great, clearly shows both the horn of Amon—indicating his status as a god—and the elephant scalp and the aegis that symbolized the divine intervention that won him victory at the Hydaspes River. With this artifact, for the very first time, we in the modern world can see Alexander as he saw himself. Ptolemy merely copied what his former sovereign had already coined. |

That alone would stand as one of the most audacious claims of any leader in history, but the gold medallion shows us that Alexander actually went further by commissioning an image that unequivocally identified him not just as god-like in his exercise of power, but as a deity in his own right. Thus, the portrait style that experts believed was Ptolemy’s innovation proves to be a bolder one still by Alexander himself. Ptolemy merely copied what his former sovereign had already conceived and coined.

For the very first time, we in the modern world can see Alexander as he saw himself. This is the only official lifetime portrait of the conqueror that has survived the ages, though just barely. It is, as well, the actual “rock” whose religious and artistic splash has rippled across the centuries—and now we know it was thrown not by Ptolemy, but by Alexander himself. This fact also explains at last the elephant scalp on the coins issued by Ptolemy, who faithfully rendered the prototype.

The larger question is why Ptolemy chose to imitate a gold medallion so closely tied to a particular battle in far-off India, and not some other. Certainly, the theological implications of the portrait provide one answer, especially in the context of Ptolemy’s struggle for Alexander’s relics. The peculiar circumstances of that conflict may give us another clue. The elephant medallions copied by Ptolemy had been designed to give Alexander credit for the fortuitous storms that gave one army advantage over the other. In the campaign of Ptolemy against Perdiccas, too, it was not only crocodiles, but also a strange meteorological phenomenon that decided the issue. Many of those who witnessed the sudden rise of the Nile wondered if a fateful thunderstorm somewhere in Upper Egypt had surreptitiously dumped enough rain into the river to trap Perdiccas’s troops in the deadly surge that swept them into the reptilian maws. From Ptolemy’s vantage point, the same divine hand may have been at work in both miracles, as if the man-god copied from the elephant medallions had personally intervened on Ptolemy’s behalf. That’s a message that would make much sense on the coinage of Egypt. Perdiccas had lost both Alexander’s body and his divine favor, much to the delight of the man who would be king —and of the crocodiles of his nascent realm.

|

The tiny village of Mir Zakah lies about 50 kilometers (30 mi) northeast of Gardez along the ancient trail from Ghazni (in today’s Afghanistan) to Gandhara (Pakistan). Countless pilgrims, criminals, warlords and refugees have passed through these badlands from Alexander’s era till today. In the third century, one or more such travelers—for reasons still unknown—dumped into a roadside watering hole what can only be described as the most amazing hoard in history. The tiny village of Mir Zakah lies about 50 kilometers (30 mi) northeast of Gardez along the ancient trail from Ghazni (in today’s Afghanistan) to Gandhara (Pakistan). Countless pilgrims, criminals, warlords and refugees have passed through these badlands from Alexander’s era till today. In the third century, one or more such travelers—for reasons still unknown—dumped into a roadside watering hole what can only be described as the most amazing hoard in history.

The first inkling of the old well’s secret came in 1947, when a villager spied something interesting at the bottom of her water bucket. Fingering an ancient gold coin, she screamed out “Zarin! Zarin! (Gold! Gold!)” to her startled neighbors. In response to her cries, a crowd of local diggers soon fetched about 13,000 more coins from the well. Eventually satisfied that everything of value had been salvaged, the residents of Mir Zakah returned to the routines of daily life.

A heavy spring rain 45 years later stirred up another gold coin. Word of the discovery traveled quickly to area warlords desperate for money to finance the long and dismal civil war. Rumors of treasure then reached the Kissakhani Bazaar along the border in Peshawar, touching off an international competition to purchase whatever the villagers of Mir Zakah could find and smuggle into Pakistan. A rough alliance of warlords, gangsters, antiquities dealers and greedy collectors converged in a well-equipped treasure hunt using generators, water pumps and large levies of workmen with shovels and pickaxes. One ancient coin became a hundred, then a thousand, later a hundred thousand—and finally more than a half-million. In the end, the Mir Zakah well yielded more than four tons of coins and 770 pounds of other gold and silver artworks. The finds included a variety of Greek, Persian and Indian artifacts. Nothing quite like this hoard had ever been seen before, and nothing like it may ever be seen again. It was as if someone had found a world-class museum at the bottom of a hole—only to sell off the contents without a moment’s regard for its value to the common heritages of history and humanity.

In 1993, a Pakistani journalist with a collector’s eye spotted the gold elephant medallion in a potato sack bulging with treasures from Mir Zakah. Initial efforts to purchase the medallion failed, but over time, an agreement was reached, and the Pakistani buyer carried off his prize to London. There, from the relatively safe haven of a private collection, the unique artifact cast into history by Alexander the Great himself continues to send ripples through time. |

|

Frank L. Holt (fholt@uh.edu) is a professor of history at the University of Houston and most recently author of Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan (2005) and Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions (2003), both published by the University of California Press. |

|

Norman MacDonald (kingmacdonald@wxs.nl) is a Canadian free-lance artist who lives in Amsterdam. His work can be viewed at www.macdonaldart.net. |