|

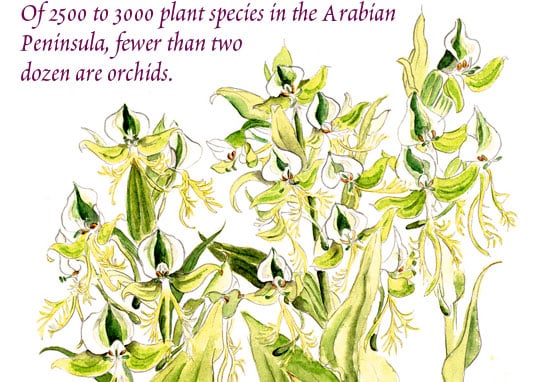

| Eulophia petersii is the most common of the Arabian Peninsula’s orchids. It flowers year-round and adapts to drought better than any other local orchid species. |

|

| Epipactis veratrifolia prefers wet habitats, such as dripping rock faces; it can be found from Turkey to Somalia to the Himalayas. |

Written by Eric Hansen

Illustrated by Barbara Evans

wasn’t looking for orchids when my driver, Abdul Ali, pulled to the side of the road at the top of the Summarah Pass between Ta’izz and Jiblah in Yemen. For a better view and to stretch our legs after a long morning in the car, we decided to hike up a grassy slope to a spot where, at around 2500 meters’ (8000') elevation, we came upon a population of unusually beautiful flowers. At the time, I didn’t I suspect that the plant was an orchid—Habenaria macanthra, to be exact—or that orchids grew anywhere in the Arabian Peninsula. I thought orchids were just exotic tropical plants that produced showy flowers for ladies’ ball gowns or the lobbies of five-star hotels. So limited was my knowledge at the time, in fact, that I assumed orchids grew only in humid jungles.

wasn’t looking for orchids when my driver, Abdul Ali, pulled to the side of the road at the top of the Summarah Pass between Ta’izz and Jiblah in Yemen. For a better view and to stretch our legs after a long morning in the car, we decided to hike up a grassy slope to a spot where, at around 2500 meters’ (8000') elevation, we came upon a population of unusually beautiful flowers. At the time, I didn’t I suspect that the plant was an orchid—Habenaria macanthra, to be exact—or that orchids grew anywhere in the Arabian Peninsula. I thought orchids were just exotic tropical plants that produced showy flowers for ladies’ ball gowns or the lobbies of five-star hotels. So limited was my knowledge at the time, in fact, that I assumed orchids grew only in humid jungles.

|

| ERIC HANSEN |

| From the tip of Yemen to southern Saudi Arabia, the western escarpments of the Arabian Peninsula catch monsoon winds carrying moisture from Central Africa eastward toward Asia. The resulting rainfall makes for the wettest environment in the Arabian Peninsula. |

As I later discovered while writing my book Orchid Fever (2001), the family Orchidaceae is an adaptable and opportunistic one with worldwide distribution over a wide range of ecological niches. Orchids are a highly evolved—and still very much evolving—group of plants. According to recent estimates, there are approximately 25,000 naturally occurring orchid species in the wild, and artificial orchid hybrids, developed for the horticultural trade, now number in the hundreds of thousands. To give an idea of their range, orchid species grow from just below the Arctic Circle southward on all continents except Antarctica. In addition to this distribution, orchids have adapted to habitats as diverse as peat bogs, forests, mountain tops, deserts and coastal areas. They grow in soil, sand, trees and rock cliffs; Rizanthella gardneri, an Australian species, spends its entire life underground, and even flowers there.

Orchids are generally classified as either lithophytes (growing on bare rock), epiphytes (growing on supporting plants, usually trees) or terrestrials (growing in the ground). All of the approximately two dozen species found in the Arabian Peninsula are terrestrials. They are characterized by their adaptations to arid conditions, including underground tubers, pseudobulbs and rhizomes that store water and nutrients. The orchids of the Arabian Peninsula occupy nine genera: Bonatea, Disa, Epipactis, Eulophia, Habenaria, Holothrix, Orchis, Satyrium and Nervilia. About two years after my walk on the Summarah Pass, at a reception at the British Embassy in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen,I met John and Barbara Evans, long-term British residents whose interest in natural history extended to orchids. As a testimony to their perseverance and good luck as amateur botanists, of the 22 reported orchid species in the Arabian Peninsula, they found nine growing in the wild in Yemen between 1981 and 1989.

|

| Habenaria macrantha is the most common of the eight known Habenaria orchids in the Peninsula, and it can grow in stony as well as grassy areas. It flowers in summer. |

They told me that to the west of Sana’a, on the terraced slopes of Jabal al-Nabi Shu‘ayb, they had even found the orchid Epipactis veratrifolia growing by a tree-shaded irrigation channel. Surprisingly enough, this orchid species, with its distinctive greenish-yellow flowers with bands of reddish purple, growing from creeping rhizomes, has a wide distribution that ranges from the mountains of Ethiopia and Somalia to the Himalayas.

|

| Tor Eigeland / Saudi Aramco World / PADIA |

| In Saudi Arabia, the ‘Asir mountains mark the northern boundary of orchid habitats. |

In our discussion that night, I mentioned the flowering plants on Summarah Pass and wondered if they might be terrestrial orchids. Barbara later sent me a copy of one of her illustrations (at right), which I compared with a photograph I had taken and a botanical illustration from the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew. I identified the plant as Habenaria macrantha—my first confirmed orchid sighting in the Peninsula. Others soon followed.

Reading up on the botany of the region, I quickly came across the account of Carsten Niebuhr’s ill-fated Danish-sponsored expedition to Yemen in 1762–1763. One of the six members of the expedition was the Swedish botanist Pehr Forsskål, who had been a student of Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy. Toward the end of the expedition, Forsskål had also crossed the Summarah Pass headed toward Sana’a, but this was 315 years before Abdul Ali and I stumbled upon our botanical discovery. At the time Forsskål crossed the pass, he was so stricken with malarial fever that he had to be tied to his camel so he wouldn’t fall off. Forsskål never saw Habenaria macrantha, and died a few days later in Yarim. His notes and specimens were transported to Copenhagen, with great difficulty, by Niebuhr—the sole survivor of the expedition—who in 1775 published Forsskål’s research as Flora Aegyptiaco–Arabica. Among the plants mentioned are three orchids: Holothrix aphylla, Eulophia streptopetala var. rueppelii and Eulophia petersii.

As a frequent visitor to Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula, I wanted to find Forsskål’s orchids for myself, and search for the Evanses’ species too. And so on my subsequent trips to the region I made a point of looking for orchids when I was out in the field, with the assistance of amateur botanists and local farmers. I also sought out historical accounts and pre-Linnaean plant studies by Arab writers, such as Kitab al-Nabat (The Book of Plants) by Abu Hanifa al-Dinawari (about 895), and Bughyat al Fallahin (partly translated as The Cultivation of Cereals in Mediaeval Yemen), compiled about 1370 for the Rasulid Sultan al-Malik al-Afdal al-‘Abbas ibn ‘Ali. As it turned out, these earlier works concentrated on cultivated crops and the economic and medicinal uses of plants, so orchids were neither collected nor identified. I then turned my attention to more contemporary accounts, written mostly by European botanists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In Saudi Arabia, my leads to orchid habitats were primarily based on the recent field work of Shaukat Chaudhary and on Sheilah Collenette’s 1985 book An Illustrated Guide to the Flowers of Saudi Arabia. In Yemen, I made good use of John Wood’s excellent 1997 Handbook of the Yemen Flora. White and Leonard’s work on the phytogeographical links between Africa and Southwest Asia was useful in determining the wider geographical range of orchid species found in the region, and P. J. Cribb’s article “The Orchids of Arabia,” published in Volume 33 of Kew Bulletin, provided a list of species and a historical overview based on the work of other botanists and taxonomists.

|

| Flowering only in March and April, Holothrix aphylla was one of three orchid species found by botanist Pehr Forsskål in 1763. Below: Clouds gather amid the mountains of central Yemen. |

|

| ERIC HANSEN |

The primary concentrations of orchid species on the Arabian Peninsula are located along the mountainous western escarpment that faces the Red Sea, starting in the ‘Asir Mountains of Saudi Arabia and extending south into Yemen. It contains the type of dense, drought-deciduous cloud forest that provides suitable habitat for terrestrial orchids. Today, these habitats have been greatly reduced and often exist as isolated pockets. They’ve been affected by thousands of years of human activity, including extensive terracing, irrigation, deforestation caused by wood collecting for cooking and building material, grazing of livestock and the introduction of imported species of plants—especially sorghum, vegetables, fruit trees, coffee and qat. But orchid habitat is also found along the northeast coast of the Arabian Peninsula, from al-Hasa Oasis near the east coast of Saudi Arabia southeast to the mountains in the Dofar region of Oman. The interior of the Arabian Peninsula, however, is too dry for orchids: It consists largely of parched rocky desert or vast seas of sand hills, both entirely unsuitable to even the most adaptable orchid species.

The majority of orchids found in the Arabian Peninsula are also found in East Africa. This close floristic relationship within what is known variously as the Saharo-Arabian Region, the Eritreo-Arabian Province or the Sudanian Region is clearly delineated on plant geographical maps of the area. Running across the bottom corner of the Arabian Peninsula to the northeast of the mountain range that faces the Red Sea is the dividing line between two major plant regions: To the south is the Paleotropic Kingdom, and to the north, the Holarctic Kingdom. This is the reason why many of the same tropical plant families and genera are found in Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and Southwest Asia. According to experts, including Al-Hubaishi and Müller-Hohenstein in An Introduction to the Vegetation of Yemen, this shared botanical history predates the rifting and creation of the Red Sea during the Tertiary period.

But getting back to my search for Forsskål’s orchids: To date, I have only located two of the three species. Holothrix aphylla remains elusive despite the Evanses’ directions to an abandoned cemetery north of Sana’a.

I searched that area on two occasions before deciding that the discovery of these 10-centimeter-tall (4") plants with three-millimeter-wide (1⁄8") flowers in that stony wasteland of gnarly scrub, dried up irrigation channels, intense heat and blinding dust storms was beyond my abilities. I fared better with the other two. By dumb luck I literally trod upon a Eulophia streptopetala var. rueppelii in flower during a walk on Jabal Milhan in 1990. A year later, while I was working on a rocky hillside near the town of al-Mahwit, a little boy handed me a meter-long (39") stem covered with amazing flowers. I asked him to show me where he had collected the flowers, and found Eulophia petersii growing in a most unlikely habitat.

Of all the orchids found in the Arabian Peninsula, Eulophia petersii is arguably one of the most robust and interesting in terms of its ability to adapt to a harsh environment, where it grows on a thin layer of soil in open, stony scrubland. Oddly enough, this plant also has one of the most beautiful blooms of all the Arabian orchids. Despite such an unforgiving habitat, the flower stem grows anywhere from 1.5 to two meters high (58–78") with large, oval, cream-colored pseudobulbs at ground level. Thick, fleshy leaves help the plant retain moisture. The showy, olive-green, brown or reddish flower petals and sepals are veined with purple, and the white, three-lobed lip has a flush of pink. In suitable habitats along the western escarpment of the Arabian Peninsula, the plant remains in flower for most of the year, and for this reason it is also one of the easiest orchids to identify.

|

| Habenaria cultrata is restricted to a narrow range of habitats in the mountains of central Yemen and Ethiopia. |

Later, in 1996, while on an assignment for this magazine to write about the history of Yemeni coffee, I visited the mountain village of al-‘Udayn, at the end of a long dusty road west of Jiblah. The area is considered prime coffee-growing country, with narrow terraced fields that climb from the riverbeds to high up on the mountains. Rich volcanic soil and steady breezes bringing moisture off the Red Sea have created a habitat ideal not only for coffee, but also for orchids.

Following the Evanses’ directions and clues from Wood’s handbook, I explored nearby Jabal al-Ta’kar, where the intrepid British ornithologist and botanist Martin Plimsole joined me in a search for the tiny flowers of the 15-centimeter-high (6") Habenaria lefebureana. Evans had described its floral scent as resembling almonds and chocolate, but unfortunately it was not the flowering season for the plant during our visit. When we returned empty-handed to al-‘Udayn late that afternoon, a sympathetic coffee grower took me to look at a flowering plant that he had recently discovered on a steep hillside of shaded scrub not far from the al-‘Udayn suq, at an elevation of approximately 1400 meters (4550').

|

| Habenaria lefebureana is "localy abundant" in upland grasslands between 2500 and 3000 meters, according to botanist J.R.I. Wood. |

The plant turned out to be an orchid, but I wasn’t immediately sure which one. It had multiple flowering stems that emerged from a mass of pyramidal pseudobulbs at the base of the plant. Each stem was arrayed with a dozen or more very attractive flowers. They had erect brownish petals, a white throat and a pinkish lip veined with lines of violet-purple. It took me almost two years to identify the plant, but eventually, thanks to the help of German orchid taxonomist Guido Braem, we confirmed it was Eulophia guineensis—one of the rarest.

My final orchid discovery, and the most unexpected, came in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, at the Date Palm Research Center near al-Hasa, which I visited while researching an article—also for this magazine—on dates. The ancient oasis is home to an estimated three million date palms. I was in the midst of discussing the technique of tissue-culturing different varieties of date palms with Abdullatif Alkhateeb, director of the center, when out of the corner of my eye I noticed a potted plant that looked nothing like a date-palm seedling. It was not in flower and it seemed half-dead, but the identification tag read: “Orchis laxiflora/ subspecies palustris.”

“Recently collected from al-Hasa oasis,” Alkhateeb told me in an offhand manner. “Collected and described in Flora Arabica by the botanist Blatter in 1919. It was the first orchid species discovered in Saudi Arabia.”

We went back to looking at the expanse of tissue-cultured date-palm seedlings, but I couldn’t help wondering how a specimen of a non-African terrestrial orchid, more commonly found in the meadows and marshlands of Europe and far across the Gulf in Iraq and Iran, had ended up living with three million irrigated date palms in al-Hasa—and to what other unexpected location it and its fellow orchid species might next adapt.

|

Eric Hansen (ekhansen@ix.netcom.com) is a free-lance photographer and the author of numerous books, including Orchid Fever (2001) and Motoring with Mohammed (1992). |

|

Barbara Evans lived in Yemen in the 1980’s while her husband served in a British government posting. Having searched out orchids earlier in East Africa, the couple took numerous walks in the mountains of Yemen, and the illustrations produced here represent only the orchid species they actually found. Now retired and living in Wales, she says, “The challenge remains to discover the rest.” |