|

Written by David W. Tschanz

Illustration by Hamra Abbas

Before him and his generals stood four emissaries from the Mongol ruler Hülegü Khan. They handed Qutuz a letter. It was not couched in the diplomatic tone usually adopted by one head of state when addressing another. Before him and his generals stood four emissaries from the Mongol ruler Hülegü Khan. They handed Qutuz a letter. It was not couched in the diplomatic tone usually adopted by one head of state when addressing another.

From the King of Kings of the East and West, the Great Khan. To Qutuz the Mamluk, who fled to escape our swords.

You should think of what happened to other countries…and submit to us. You have heard how we have conquered a vast empire and have purified the earth of the disorders that tainted it. We have conquered vast areas, massacring all the people. You cannot escape from the terror of our armies.

Where can you flee? What road will you use to escape us? Our horses are swift, our arrows sharp, our swords like thunderbolts, our hearts as hard as the mountains, our soldiers as numerous as the sand. Fortresses will not detain us, nor arms stop us. Your prayers to God will not avail against us. We are not moved by tears nor touched by lamentations. Only those who beg our protection will be safe.

Hasten your reply before the fire of war is kindled…. Resist and you will suffer the most terrible catastrophes. We will shatter your mosques and reveal the weakness of your God, and then we will kill your children and your old men together.

At present you are the only enemy against whom we have to march.

|

Qutuz withdrew, commanding his generals to follow him. Their impromptu council of war was held in light of chilling facts.

even years earlier, in 1253, Hülegü Khan (“khan” derives from the Turkic han, “prince”), brother of the Great Khan Möngke and a grandson of Genghis Khan, had been told to gather his forces and move into Syria “as far as the borders of Egypt.” His mission was to conquer those lands as a step toward Genghis Khan’s unabashed goal: world Mongol rule.

even years earlier, in 1253, Hülegü Khan (“khan” derives from the Turkic han, “prince”), brother of the Great Khan Möngke and a grandson of Genghis Khan, had been told to gather his forces and move into Syria “as far as the borders of Egypt.” His mission was to conquer those lands as a step toward Genghis Khan’s unabashed goal: world Mongol rule.

|

| MAPPING SPECIALISTS |

Scholars debate the exact size of Hülegü’s force, but it was enormous by the standards of the time. The ordu (“army” in Turkic, from which comes the English “horde”) comprised approximately 300,000 warriors, all master horsemen and archers. Their training, discipline, reconnaissance, mobility and communications far surpassed those of any contemporary force. Organized in units based on factors of 10, they could cover 100 miles in a day. Including women, children and other noncombatants, the entire host numbered, by conservative estimates, about two million.

The Mongols arrived in Persia from the east in 1256 to settle an old score with the formidable Assassins, who had plotted to murder the Great Khan. Their revenge was a two-year campaign of conquest against 200 fortresses scattered across northern Iran, Syria and Lebanon. Located atop mountains and considered impregnable, they were known as “eagles’ nests,” after the name of the main Assassin redoubt at Alamut.

|

| JOHN FEENEY / SAUDI ARAMCO WORLD / PADIA |

| In Cairo, not far from the palace where Sultan Qutuz received the Mongol messengers, the fortified city gate Bab Zuwayla stands today. |

Yet the Mongols moved out from the Elbruz Mountains of northeastern Iran, reducing fortress after fortress with workmanlike efficiency. Chinese engineers set up siege engines, and one by one the eagles’ nests fell, and the Assassins were destroyed.

Hülegü then turned his attention to Mesopotamia and the Abbasid capital, Baghdad. Though no longer the center of political power in the Islamic world—that now lay in Cairo—it remained the intellectual heart of Islam. No longer: In February 1258 it was sacked and burnt in one of the most brutal conquests of the age. More than any other Mongol act, Baghdad’s conquest shook the entire Islamic world. Hülegü fell back to Tabriz in northern Iran, while lesser potentates along the Mongols’ line of travel came and did him homage.

Among those offering an alliance to Hülegü was Hayton, the Christian king of Armenia. Hayton regarded the Mongols’ invasion as a new crusade to free Jerusalem from the Muslims, who had retaken the city from the Crusaders only recently, in 1244. His perception was encouraged by Hülegü’s chief lieutenant, Kitbuqa, who was not only a Christian, but also claimed to be a direct descendant of one of the three Magi who had brought gifts to the infant Jesus. Following his visit to the Mongol leader, Hayton sent messages to his Crusader neighbors that Hülegü was about to be baptized a Christian, and strongly urged that they too ally themselves with this new force, and turn it to the Crusader cause.

|

| BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE, PARIS / ART RESOURCE |

| This 14th-century Persian manuscript shows Genghis Khan and three of his four sons. The youngest, Tolui, fathered Möngke and Hülegü; it was the death of Möngke in early 1260 that prompted the pullback of Hülegü’s army, leaving a much smaller Mongol force to advance on Egypt. |

In September 1259, Hülegü moved his army again, quickly subduing all of Mesopotamia east of the Tigris. Then he crossed the Euphrates on a pontoon bridge at Manbij, in present-day Syria. The Ayyubid sultan of Syria, Al-Malik al-Nasir, offered to submit, but he was rebuffed. He organized the defense of Aleppo, then fell back to prepare Damascus. The Mongol army, now 300,000 strong, arrived at Aleppo on January 13, 1260. Engineers deployed catapults, and the city fell in a matter of days. Aleppo suffered Baghdad’s fate. This had the desired effect on the citizens of Damascus, who drove Al-Nasir from the city and sent an unconditional surrender. Hülegü entered the city accompanied by Kitbuqa, Hayton and Bohemond IV, the Crusader prince of Antioch who had heeded Hayton’s advice. Al-Nasir fled toward Egypt, but Mongol soldiers caught up with him near Gaza, and he was taken to Hülegü’s court in chains.

|

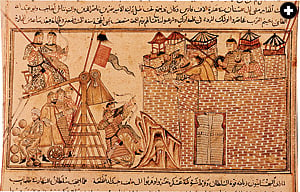

| EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY LIBRARY |

| From 1256 to 1258, the Mongol forces deployed an estimated 300,000 warriors as well as siege engines, like the trebuchet being prepared for use above, to subdue more than 200 fortresses in northern Iran and the Levant. |

It was at this time that Hülegü dispatched his emissaries to spread fear in Cairo.

utuz was a Mamluk, raised and educated as a warrior. As distasteful as an ultimatum might be, he was also a realist: To his generals, he admitted that the Mamluks were probably no match for the Mongols. The commanders agreed, and they recommended capitulation.

utuz was a Mamluk, raised and educated as a warrior. As distasteful as an ultimatum might be, he was also a realist: To his generals, he admitted that the Mamluks were probably no match for the Mongols. The commanders agreed, and they recommended capitulation.

But that was not Qutuz’s decision. He had come to power by knowing when to take decisive action: Observing the weak character of the 15-year-old sultan Nur al-Din ‘Ali, Qutuz had deposed him four months earlier. He was not about to surrender without a fight. Qutuz ordered his guards to execute the envoys, and his generals he ordered to prepare to defend the city.

Hülegü’s vast army made ready for the long-awaited march on Egypt. It outnumbered the 20,000-man Mamluk army 15 to 1. The survival of Cairo—and perhaps the fate of Islamic civilization—hung in the balance.

Then fate intervened.

|

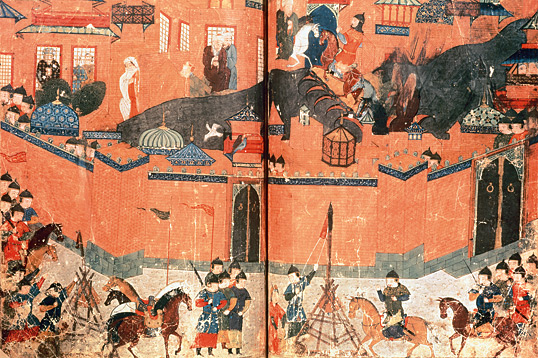

| BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE, PARIS / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| A 14th-century Persian depiction of the February 1258 sack of Baghdad. |

A messenger came to Hülegü with word that the Great Khan, Möngke, had died in Karakoram and, in keeping with Mongol tradition, all the princes, including Hülegü, were summoned there at once to elect his successor. Hülegü pulled his main army back to Maragheh and, apparently confident of victory, he ordered Kitbuqa, camped in Syria with 20,000 men, to press on to Egypt.

A messenger came to Hülegü with word that the Great Khan, Möngke, had died in Karakoram and, in keeping with Mongol tradition, all the princes, including Hülegü, were summoned there at once to elect his successor. Hülegü pulled his main army back to Maragheh and, apparently confident of victory, he ordered Kitbuqa, camped in Syria with 20,000 men, to press on to Egypt.

A few weeks later, Qutuz picked up an unexpected ally in Baybars, the leader of a rival Mamluk group that had been offended by Qutuz’s rise to power. Baybars and his supporters were based in Syria, from where he had been launching raids on Egypt, but Baybars realized that the fall of Qutuz would also crush his own aspirations, and so when Damascus fell, Baybars offered Qutuz his support.

Kitbuqa sent a raiding party into Palestine, cutting a swath of destruction through Nablus all the way to Gaza, but it avoided attacking the narrow strip of Crusader-held territory along the coast. The Crusaders, too weak to provide any significant resistance to the Mongols on their own, became further embroiled in the debate over whether or not to ally themselves with the invaders. Kitbuqa hoped his show of relative restraint would sway the argument in his favor. He was wrong.

Two Crusader leaders, John of Beirut and Julian of Sidon, launched retaliatory raids on the new Mongol-held territories. Kitbuqa, in turn, sent a punitive expedition against Sidon, which was plundered and its citizens massacred. Christian ardor for the Mongol cause cooled considerably, and turned colder still when news reached the Crusaders that another Mongol army had invaded Poland.

|

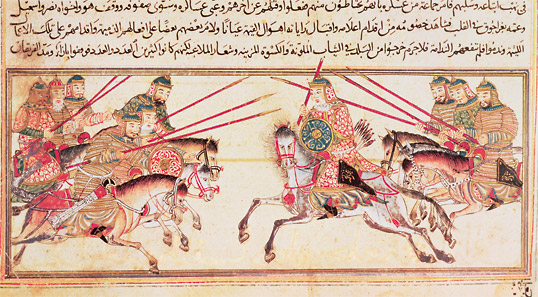

| CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY |

| Mamluk cavalrymen canter around a pool in this page from the Compendium of Military Arts, written in Cairo and dated 1366. |

The word mamluk means “one who is owned.” The term was originally applied to boys from Central Asian tribes who were bought by the Abbasid caliphs and raised to be soldiers. The same practice was adopted by the Fatimids, an Ismaili dynasty based in Tunisia that conquered Egypt in 969 and founded Cairo as its new capital.

When Salah ad-Din (Saladin to the West), the son of a Kurdish general, supplanted the Fatimids and founded the Ayyubid dynasty in 1174, he formed the Mamluks into a distinct military body. Since the Ayyubids were strangers in Egypt, they likely felt more comfortable with the support of their fellow foreigners.

Slave traders bought the children of conquered tribes in Central Asia, promising them security, discipline and the possibility of great fortunes. Mamluk boys then endured several years of rigorous training in horsemanship and archery. They were used both as royal bodyguards and to offset the dominating influence of the Arab military in the state. Not to be confused with ordinary slaves, the Mamluks were members of an elite military corps—a kind of proto-Foreign Legion or a knighthood of Islam. In 1254, the Mamluks revolted against the Ayyubid ruler and one of their own—a Turk named Aybak—married Shagar al-Durr, the wife of the murdered sultan: The Mamluks had accomplished the rare feat of transforming themselves from slaves to masters.

Power in the Mamluk realm was not based on heredity. Every Mamluk arrived in Egypt or Syria as a slave- soldier. The young men were converted to Islam and worked their way up the ranks on merit alone. Every commander of the army and nearly all of the Mamuk sultans started life in this way. The result was a succession of rulers of unbounded ambition, courage and ruthlessness.

After the Mamluks made themselves masters of Egypt and Syria, they continued the tradition of recruiting foreigners for their military. Agents were sent to buy and import boys from Central Asian tribes, chiefly Circassians, Turkomans and Mongols. Mamluks looked on their Egyptian-born sons as socially inferior and would not recruit them into regular Mamluk units, which only admitted boys born on the steppes.

This constant influx of new blood prevented the dynasty from decaying from within as a result of less-capable princes ascending to the throne, but it also made for turmoil at the top: While some Mamluk sultans ruled for a decade or more, the average length of rule was only five years. As an autocratic military caste, the Mamluks ruled with considerable harshness, imposing heavy taxes and holding all political and military power. They did employ the native-born population in civil posts; such persons often achieved high rank and honors in the civil administration. In contrast to their harsh reputation as rulers, the Mamluks also bequeathed an astonishing legacy of artistic achievement. Much of the glory of medieval Cairo still visible today is the result of Mamluk patronage.

The Mamluks ruled Egypt until 1517, when Cairo fell to the Ottoman Turks whose artillery and firearm skills far surpassed that of the Mamluks who, as consummate horsemen, disdained such novelties. The Ottoman ruler, Selim i, ended the Mamluk sultanate but did not destroy the Mamluks as a class; they kept their lands, and Mamluk governors retained control of the provinces and were even allowed to keep private armies.

In the 18th century, when Ottoman power began to decline, the Mamluks were able to win back an increasing amount of self-rule. In 1769 a Mamluk leader, Ali Bey, proclaimed himself sultan and declared independence from the Ottomans. Although his reign collapsed in 1772, the Ottoman Turks still felt compelled to concede increasing measures of autonomy to the Mamluks and appointed a series of them as governors of Egypt. The last great charge of the fabled Mamluk horsemen took place on July 17, 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte’s modern army shattered the Egyptian cavalry at the Battle of the Pyramids. Their power as an elite class ended in 1811 when Muhammad Ali, an Albanian Turk who had wrested control of Egypt from the Ottomans in 1805, invited several hundred prominent Mamluks to dinner in the Cairo Citadel. After diner, as the Mamluk notables and their entourages made their way to one of the fortress’s lower gates, Muhammad Ali’s troops massacred them all, a violent final chapter for a dynasty whose rulers rose from slavery to control much of the Middle East. |

|

| There are three enlargeable segments to this photo.PRIVATE COLLECTION / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| A Chinese painting shows a small Mongol convoy. Mongol cavalrymen each had three mounts and traveled very light: Each man wore a silk shirt under a tunic, and heavy cavalry also wore chain mail and a leather cuirass. Each carried a leather-covered wicker shield and a helmet of either leather or iron, depending on rank, and was armed with two composite bows and 60 arrows. Soldiers also carried clothing, cooking pots, dried meat and water in a saddlebag made from a cow’s stomach, which, being waterproof and inflatable, could also be used as a float to cross rivers. Thus equipped, the cavalry could travel up to 160 kilometers (100 mi) a day. |

Almost simultaneously, William of Rubruck, the envoy to the Mongols from the French Crusader king Louis IX, returned from Mongolia with a complete report. After reading it, Pope Alexander IV sent word throughout Christendom that anyone making an alliance with them would be excommunicated. This deprived the Mongols of any Christian support.

When news reached Qutuz of Hülegü’s withdrawal to Karakoram, he realized at once that the military situation had been transformed to his advantage. He ordered a halt to defensive preparations and commanded his men instead to prepare to advance against the Mongols. In another audacious move, he sent envoys to the Crusader leaders in Acre asking for safe passage and the right to purchase supplies.

For the surprised Franks, the request presented a dilemma. To cooperate with Qutuz would mark the Crusaders clearly as enemies of the Mongols, exposing them to the notorious Mongol wrath; on the other hand, Qutuz was their only hope of ridding the region of them. After a lengthy debate, they acceded.

On July 26, 1260, the Egyptian army began its march northeast. Near Gaza, Baybars’s vanguard destroyed a small Mongol force on long-range patrol. Kitbuqa, from his base at Baalbek (today in central Lebanon), assembled his army and began a march to the south, down the eastern side of Lake Tiberias.

On July 26, 1260, the Egyptian army began its march northeast. Near Gaza, Baybars’s vanguard destroyed a small Mongol force on long-range patrol. Kitbuqa, from his base at Baalbek (today in central Lebanon), assembled his army and began a march to the south, down the eastern side of Lake Tiberias.

On the outskirts of Acre, while the nervous Crusader leaders watched the Mamluk army pitch its tents in the shadow of their city, Qutuz purchased supplies and planned his next move. Word soon arrived that the Mongols, and a large contingent of Syrian conscripts, had circled Lake Tiberias, and they were approaching the Jordan River along the same invasion route used by Saladin in 1183. Qutuz moved his army southeast to meet them.

On September 3, Kitbuqa turned west across the Jordan and up into the hills to the Plain of Esdraelon. Qutuz established positions at ‘Ain Jalut (“the Spring of Goliath”). There, the plain narrowed to just under five kilometers (3 mi), protected on the south by the steep slope of Mount Gilboa and on the north by the hills of Galilee. Qutuz concealed units of Mamluk cavalry in the surrounding hills, and ordered Baybars and the vanguard forward against an enemy who had never tasted defeat.

aybars quickly made contact with Kitbuqa’s force as it came toward ‘Ain Jalut. As Qutuz hoped, Kitbuqa mistook it for the whole of the Mamluk army, and Kitbuqa ordered a charge, leading the attack himself. The forces collided and seemed to check each other in the fierce clash that followed; then Baybars ordered a retreat. The Mongols rode confidently in pursuit, victory seemingly in their grasp.

aybars quickly made contact with Kitbuqa’s force as it came toward ‘Ain Jalut. As Qutuz hoped, Kitbuqa mistook it for the whole of the Mamluk army, and Kitbuqa ordered a charge, leading the attack himself. The forces collided and seemed to check each other in the fierce clash that followed; then Baybars ordered a retreat. The Mongols rode confidently in pursuit, victory seemingly in their grasp.

|

| PRIVATE COLLECTION / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| In the late 13th century, Mongol rulers in Iran, the Levant and Central Asia became increasingly embroiled in internecine conflicts, and they were never again strong enough to threaten Egypt. |

When they reached the springs, Baybars ordered his army to wheel and face the enemy. Only then did the Mongols realize they had been tricked by one of their own favorite tactics: the feigned retreat. As Baybars reengaged the Mongols, Qutuz ordered the reserve cavalries to sweep out from the foothills to attack the Mongol flanks.

Kitbuqa ordered a charge to the Mamluk left flank. It held, wavered, held again and then was turned, cracking under the ferocity of the Mongol assault.

As the Mamluk wing threatened to dissolve and it appeared the army might be routed, Qutuz rode to the site of the fiercest fighting and threw his helmet to the ground so the entire army could recognize his face. “O Muslims!” he shouted three times. His shaken troops rallied, and the flank held. As the line solidified, Qutuz led a countercharge that swept the Mongols back.

As the Mamluk wing threatened to dissolve and it appeared the army might be routed, Qutuz rode to the site of the fiercest fighting and threw his helmet to the ground so the entire army could recognize his face. “O Muslims!” he shouted three times. His shaken troops rallied, and the flank held. As the line solidified, Qutuz led a countercharge that swept the Mongols back.

Despite the Mamluk pressure, Kitbuqa too continued to rally. Then his horse took an arrow, and he was thrown to the ground. Captured by nearby Mamluk soldiers, he was taken to Qutuz and executed.

With their leader gone, the remaining Mongols fled 12 kilometers (7 1¼2 mi) to the town of Beisan, the Mamluks in pursuit. The survivors fled far to the east, across the Euphrates. Within days, the victorious Qutuz reentered Damascus in triumph, and the Mamluks moved on to liberate Aleppo and the other major cities of Syria.

he clash of Mamluk and Mongol at ‘Ain Jalut was one of the most significant battles of world history —comparable to Marathon, Salamis, Lepanto, Chalons and Tours—in that it set the future course of both Islamic and western civilization. Had the Mongols succeeded in conquering Egypt, they might have been able, following the return of Hülegü, to carry on across North Africa to the Straits of Gibraltar. Europe would have been surrounded from Poland to Spain. Under such circumstances, would the European Renaissance have occurred? Its foundations would certainly have been far weaker. The world today might have been a considerably different place.

he clash of Mamluk and Mongol at ‘Ain Jalut was one of the most significant battles of world history —comparable to Marathon, Salamis, Lepanto, Chalons and Tours—in that it set the future course of both Islamic and western civilization. Had the Mongols succeeded in conquering Egypt, they might have been able, following the return of Hülegü, to carry on across North Africa to the Straits of Gibraltar. Europe would have been surrounded from Poland to Spain. Under such circumstances, would the European Renaissance have occurred? Its foundations would certainly have been far weaker. The world today might have been a considerably different place.

|

| TOPKAPI PALACE MUSEUM / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| A Mongol herdsman stands with his grazing horse. Behind the mobile Mongol warriors was a host of men, women and children who maintained the fighters’ weapons and other material, cooked, ensured water supplies and tended herds. |

As it was, the Mamluks not only stopped the Mongols’ westward advance, but—just as important— they also smashed the myth of Mongol invincibility. The Mongols’ belief in themselves was never quite the same, and ‘Ain Jalut marked the end of any concerted campaign by the Mongols in the Levant.

In saving Cairo from the fate of Baghdad, the battle of ‘Ain Jalut also sealed the doom of the relatively weaker remaining Crusader states. Mamluk Egypt rose to the pinnacle of Islamic political, military and cultural power, a position it maintained until the rise of the Ottomans some 200 years later.

As for Qutuz himself, however, the fruits of victory were snatched quickly from his hand. After Aleppo was retaken, Baybars suggested that, in recognition of his contributions to the campaign, he himself be given command of the region. Qutuz refused. When the Mamluk army was only a few days from its triumphal return to Cairo, Baybars went to see Qutuz on the pretense of a matter of state. Reaching out as if in greeting, he drew a dagger and drove it into Qutuz’s heart. Qutuz had ridden out of Cairo to meet the Mongol challenge, but it was Baybars who rode home triumphant as sultan, and to this day, his story can be heard in the shadow-plays in the back streets of old Cairo.

|

| STAATLICHE MUSEEN ZU BERLIN / PREUßISCHER KULTURBESITZ / MUSEUM FÜR ISLAMISCHE KUNST |

| Baybars, Qutuz’s ally and assassin, is remembered less for perfidy and more for his many achievements following the victory at ‘Ain Jalut: 17 years of largely successful military campaigns against other Mongol forces, and more than 20 victories against Crusaders. This leather silhouette, from a Cairo shadow-play, depicts his army at sea en route to attack a Crusader port. |

|

David W. Tschanz (desertwriter1121@yahoo.com) has degrees in history and epidemiology and works for Saudi Aramco Medical Services in Dhahran. He is the editor of the military history journal Cry “Havoc!” and was contributing editor of COMMAND magazine, specializing in medical military history. He is currently at work on his seventh book. |

|

Painter and sculptor Hamra Abbas (hamraabbas@yahoo.com) was born in Kuwait in 1976. She lives and works in Berlin and Lahore. |