n the late 15th century, just as the last Islamic kingdom in Spain was giving way to the Christian reconquista, new Muslim rulers were emerging in the Malay Archipelago halfway around the world. The Kingdom of Granada in al-Andalus—Arab Spain—differed in almost every respect from the Sultanate of Sulu in the southern Philippines, but they shared a religion that shaped their culture. Islam not only determined such quotidian details as what Muslims ate and drank—or didn’t drink—it also encouraged a distinctive approach to art.

n the late 15th century, just as the last Islamic kingdom in Spain was giving way to the Christian reconquista, new Muslim rulers were emerging in the Malay Archipelago halfway around the world. The Kingdom of Granada in al-Andalus—Arab Spain—differed in almost every respect from the Sultanate of Sulu in the southern Philippines, but they shared a religion that shaped their culture. Islam not only determined such quotidian details as what Muslims ate and drank—or didn’t drink—it also encouraged a distinctive approach to art.

The contribution of al-Andalus to Spanish art is inescapable. Whether describing Washington Irving’s “dreamy palace,” the Alhambra, or the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the words “Spanish” and “Muslim” fit comfortably together. At the other end of the Muslim world, the Islamic content of Southeast Asian art is much less appreciated.

The exhibition The Message & the Monsoon: Islamic Art of Southeast Asia, held at the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia in 2005, thus blazed a new trail. As the show’s title suggests, there was a close connection between the arrival of Islam in the Malay Archipelago and the archipelago’s posi-tion on the monsoon route. In the age before steamships, wind power was the engine of seaborne trade—trade in ideas as well as goods—and the Asian monsoons were among the most spectacular means of propulsion on any ocean. They remain highly dependable today, though these days they are more likely to carry smoke from Indonesian forest fires than cargoes of goods and ideas.

The Muslim merchants who began visiting Southeast Asia in the seventh century came from India, China and Arabia. They found a wide variety of communities holding an array of beliefs. These societies ranged from the sophisticated Hindu–Buddhist Srivijayan Empire, which, at its height in the ninth century, controlled most of the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra and West Java, to animist hunter-gatherer hill tribes in the upland areas of Borneo, the smaller islands of the archipelago and the interior of the Malay Peninsula.

Most traders conducted their business in the coastal areas. They impressed local rulers with their learning and their economic power; over time, many of these rulers embraced Islam. Once the elite had converted, the rest of the society soon followed.

The first Muslim sultanate in the archipelago was established in the 13th century at its most westerly point, Aceh, which became known as the “verandah of Makkah,” and by the 15th century Islam was the religion of much of maritime Southeast Asia. In parts of the region, inhabitants became Christian in the 15th and 16th centuries. In remote inland areas, meanwhile, some of the old rock-worshiping ways have endured into the 21st century. The last outpost of Hinduism is Bali, and Buddhism exists in the region thanks to a 20th-century influx of emigrants from China.

The Islamic nature of Malay art is usually easier to see when it is compared with the art of these other communities. In many cases, its most obvious feature is an absence of what the others have in abundance. Hindus, Buddhists and Christians have religious images; animist societies have a complex pantheon that is often expressed in a highly figural manner. Islam’s most obvious contribution was to raise calligraphy to the highest art form. At the same time, Islamic art does not make the obvious distinction between the sacred and the secular that is so evident in other communities. Because Islam has so few objects that are specifically religious, there is room for many other items to acquire a spiritual dimension.

Catholicism made a more immediately visible artistic impact in the areas where it took root, mainly in the Philippines, beginning in the 1500’s, and nowhere is it more obvious where the two great monotheistic religions of Southeast Asia differ. The line that divides the Muslim south of the Philippines from the rest of the island group is still apparent. Apart from where Protestant evangelical Christianity has made inroads into Catholic territory, this is a land in which the religious icon is supreme. In the southern Philippines, the aniconic Muslim approach prevails.

The people of Southeast Asia who embraced Islam adopted changes in their lifestyles, including a new approach to the arts. The images of deities that filled the Malay Archipelago were soon replaced by a new esthetic: the word of God. Figural imagery, whether of people or animals, disappeared almost entirely—to a far greater extent than in many other Islamic societies.

Despite this, some images of God’s creatures persisted in cultural expressions such as circumcision ceremonies, when depictions of such Hindu– Buddhist deities as Garuda were used. These could be as large as the six-meter-high (20') palanquins in the shape of a bird known as the burung petala indra that carried newly circumcised princes through the crowded streets of Kota Baru on the east coast of Malaysia until the 1930’s.

The bird is one of the few living creatures that turns up regularly in Malay Islamic art. Its most surprising manifestation is on calligraphic batik cloths. Resembling a dove, this representation is composed of letters from Qur’anic verses or from pseudo-calligraphy intended to resemble holy words. The bird has none of the fearsome aspects of Garuda. It looks well-fed and friendly, a symbol of good fortune. This is exactly the role that birds generally play in Islam, although they are seldom depicted as charmingly as in the Malay world. They also appear in the Qur’an. In one reference (Chapter 3, Verse 49), the annunciation to Mary includes the future words of the Prophet Jesus:

The cultures that brought Islam to Southeast Asia made changes to religious life without denting the old concept of divine kingship. Nor did they affect all the art created by the region’s recently converted. The mosques that were built to replace temples as places of worship usually looked very much as the temples had. Indeed, until the colonial era in the 19th century, the region’s mosques— built on stilts and with square, stupa-like roofs—were quite different from what is now considered “Islamic architecture.”

In another link to the past, yellow remains a symbol of kingship. Today, it is still a matter of etiquette to avoid wearing yellow in the presence of royalty in countries such as Malaysia. In fact, rulers retained much of the reli- gious influence they had previously enjoyed, having moved from the priestly caste to become the local representatives of Islam. The hierarchical structure of Hindu society was maintained to a much greater extent in the Malay Archipelago than in some other parts of the Islamic world. Among the Malay sultanates there was less of the egalitarianism of tribal societies that we know from the Arabian Peninsula.

A sense of hierarchy is also present in the art of the Malay world. Although it was never officially spelled out—as it was in China, where books of connoisseurship were always in demand—there was a clear sense of which objects occupied the higher rungs of the esthetic ladder.

s in every Muslim society, the word of God surpassed everything else. At the apex was the Qur’an. While it is possible to write its 114 chapters on anything from a wall-hanging to a talismanic shirt, the calligrapher’s preferred form was a book. Malay copies of the Qur’an are among the least appreciated of Southeast Asian contributions to Islamic art, perhaps because they are not as dazzling to the eye as Ottoman, Iranian or Mughal manuscripts. It is rare, for example, to see a Southeast Asian copy of the Qur’an with a profusion of gold illumination. Nor do these books tend to last very long: The climate of tropical Southeast Asia is not kind to any artifact, and works on paper are the first victims of humidity and insect infestation.

s in every Muslim society, the word of God surpassed everything else. At the apex was the Qur’an. While it is possible to write its 114 chapters on anything from a wall-hanging to a talismanic shirt, the calligrapher’s preferred form was a book. Malay copies of the Qur’an are among the least appreciated of Southeast Asian contributions to Islamic art, perhaps because they are not as dazzling to the eye as Ottoman, Iranian or Mughal manuscripts. It is rare, for example, to see a Southeast Asian copy of the Qur’an with a profusion of gold illumination. Nor do these books tend to last very long: The climate of tropical Southeast Asia is not kind to any artifact, and works on paper are the first victims of humidity and insect infestation.

There is another element that has been especially damag-ing to Southeast Asian manuscripts: iron-gall ink. Easily made from inexpensive, readily available ingredients (vegetable tannin from oak galls or other sources, iron sulphate, gum arabic and water), iron-gall ink is indelible and stable in light. Over time, however, especially in a damp environment, chemical processes result in deterioration of the ink. It turns from a velvety blue-black to dark brown and the calligraphers’ work starts to look smudged. Ultimately, the ink can actively eat through the paper it is written on and can corrode an entire book.

There is another element that has been especially damag-ing to Southeast Asian manuscripts: iron-gall ink. Easily made from inexpensive, readily available ingredients (vegetable tannin from oak galls or other sources, iron sulphate, gum arabic and water), iron-gall ink is indelible and stable in light. Over time, however, especially in a damp environment, chemical processes result in deterioration of the ink. It turns from a velvety blue-black to dark brown and the calligraphers’ work starts to look smudged. Ultimately, the ink can actively eat through the paper it is written on and can corrode an entire book.

As with all the finer works of the Malay world, manuscripts were a product of royal court culture which was also the center of religious scholarship. As well as commissioning books, rulers often took part in court discourse, debating with their own scholars and welcoming foreign visitors. In the 14th century, the North African traveler Ibn Battuta wrote of his time at the court of the Sumatran king, “Al-Malik Al-Zahir Jamal al-Din, one of the most eminent and generous of princes, of the sect of Shafia, and a lover of the professors of Muslim law. The learned are admitted to his society, and hold free converse with him, while he proposes questions for their discussion.” The “Shafia” school he refers to is one of the four schools of jurisprudence that comprise Sunni Islam.

The writing itself is usually not the most distinctive aspect of a manuscript. Although calligraphers in Southeast Asia were given the same honored position as elsewhere in the Islamic world, none seems to have achieved celebrity status. The absence of a colophon, or calligrapher’s “credit,” on most of their works means that we know even less about Malay calligraphers than their counterparts elsewhere. This is very much in keeping with regional culture, in which artisans worked with more anonymity than in the Islamic heartlands.

A key feature that Malay manuscripts share is the inspiration of the natural world. This is not surprising in an environment where nature’s bounty imposes itself so vigorously. In Southeast Asia there is a profusion of greenery that has made its way into every art form. Tendrils meander through manuscripts, metalwork, woodwork and textiles. Stylized fruits and flowers are never far away.

Other striking features of Malay manuscripts are their geometry and colors. Red, blue and black are combined to extraordinary effect. The designs often have pronounced triangular features that are similarly eye-catching.

With the demise of royal patronage in the 20th century, calligraphy and manuscript illumination went the same way as every other court art. Western luxury goods have since proved to be a more tempting prospect for those who can afford them.

alligraphy was also the supreme art in many media unrelated to books: textiles, for example. This is the field of Southeast Asian art that excites collectors as much today as it has in centuries past, and one in which the most outstanding Islamic element is calligraphy.

alligraphy was also the supreme art in many media unrelated to books: textiles, for example. This is the field of Southeast Asian art that excites collectors as much today as it has in centuries past, and one in which the most outstanding Islamic element is calligraphy.

Southeast Asian textiles are rarely viewed as “Islamic art,” however. They tend to be secular in appearance and are often similar to the works of neighboring non-Muslim societies. Their most Islamic aspect is a negative: the absence of the figural imagery that forms a vital category of subject matter for the region’s other communities.

Cloth, either as clothing or as lengths of material hung on a wall or draped across furniture, was among the most highly valued of all regional heirlooms. While many rulers around the world have emphasized personal fashion, their garments were never their greatest financial asset. In the Malay world, a man’s worth might truly have been measured by the shirt on his back, or more likely the sarong around his waist. As Ma Huan, a Muslim member of Chinese admiral Zheng He’s legendary 15th-century armadas, noted of a Javanese Muslim king,“He has no robe on his person; around the lower part he has one or two embroidered kerchiefs of silk. In addition, he uses a figured silk-gauze or silk-hemp to bind the kerchiefs around his waist.”

Cloth, either as clothing or as lengths of material hung on a wall or draped across furniture, was among the most highly valued of all regional heirlooms. While many rulers around the world have emphasized personal fashion, their garments were never their greatest financial asset. In the Malay world, a man’s worth might truly have been measured by the shirt on his back, or more likely the sarong around his waist. As Ma Huan, a Muslim member of Chinese admiral Zheng He’s legendary 15th-century armadas, noted of a Javanese Muslim king,“He has no robe on his person; around the lower part he has one or two embroidered kerchiefs of silk. In addition, he uses a figured silk-gauze or silk-hemp to bind the kerchiefs around his waist.”

While luxury batik and songket textiles popular in the past are still produced in Southeast Asia, their significance is not what it was a hundred years ago, and certainly not what it was 500 years ago. The widespread adoption of western clothing in the 20th century undercut the need to express one’s status with locally made textiles, nearly putting an end to a weaving tradition that was extremely labor intensive.

The most prized of all Malay textiles today are songket weavings—a shiny form of brocade—whose gold threads give them an air of unsurpassed luxury. This is achieved by the addition of extra weft threads wrapped in gold. In the past, the top of the textile tree was occupied by ikat weavings with religious inscriptions. The ikat tie-dye process, perfected in the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra, is now almost extinct, especially in its calligraphic form, and few examples have survived. Their inscriptions are uncompromisingly religious: usually the word Allah or the Muslim profession of faith, “There is no god but God; Muhammad is the Messenger of God.”

The other calligraphic textiles of Southeast Asia had a lower status than the songkets or ikats. They were usually made of batik, a simpler wax-resist process that was less closely associated with royal courts. Though in Java and Sumatra some batik designs were considered so special that only rulers could wear them, calligraphic cloth was not in this category. Batiks with writing served purposes that are not clearly understood. Many were used as coffin covers. Others were turned into headdresses. Their talismanic value was paramount and they would never have been used as a sarong or any other sort of clothing that would come in contact with parts of the human body considered impure.

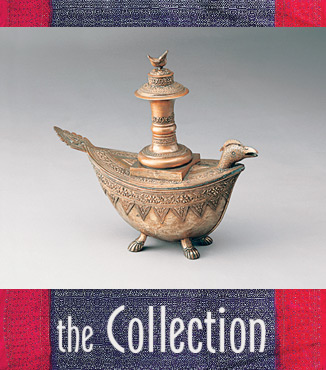

he supreme expression of mystical power in the Malay world is the distinctive dagger with a wavy blade known as a keris. It is inseparable from Southeast Asian his-tory. In addition to being a weapon, a talisman and a symbol of manhood, it is also regarded as a work of art. Examples of early keris exist in numerous European royal collections. In Islamic Southeast Asia they appear in every royal arsenal and remain part of the regalia in royal courts of Indonesia and Malaysia.

he supreme expression of mystical power in the Malay world is the distinctive dagger with a wavy blade known as a keris. It is inseparable from Southeast Asian his-tory. In addition to being a weapon, a talisman and a symbol of manhood, it is also regarded as a work of art. Examples of early keris exist in numerous European royal collections. In Islamic Southeast Asia they appear in every royal arsenal and remain part of the regalia in royal courts of Indonesia and Malaysia.

Tales of the supernatural strength of the keris are so common that it is impossible to go far into any Malay account of the occult without finding a reference to this weapon. In almost every case, the keris serves the forces of righteousness and saves the day, though occasionally the confidence of its user is misplaced. The 1857 edition of the Journal of the Indian Archipelago examined the case of a “very old and decrepit villager” in possession of a magic keris who attempted to kill a tiger that had been ravaging his neighborhood. “The astonished beast immediately struck him down and would have killed him on the spot had not one of a band of youths who had followed at some distance behind the old man, shot it,” reported the Journal.

Such incidents are extremely rare in Malay literature, where the keris is a weapon closely linked to Islam as well as to vestiges of pre-Islamic superstition in the region. Its origins are hotly debated. Although the earliest examples are from the time when Islam became a major force in Southeast Asia, it is acknowledged that this is a weapon with a Hindu–Buddhist past.

By the 14th century, the keris had become a ubiquitous feature of Muslim communities throughout Southeast Asia. Few non-Muslims adopted it, apart from the Hindu inhabitants of Bali, whose keris were distinguished only by hilts with figural carving. In most cases, the development of the keris shows how effectively Islam had taken root in its new Southeast Asian home. The hilt in particular went through an iconoclastic evolution. In idol-worshiping times, the figures of Vishnu, Shiva and other members of the Hindu pantheon predominated. The most famous type of hilt, known as jawa demam (“feverish Javanese”), was transformed from a distinctly anthropomorphic design to an abstract birdlike figure that looks very distant from the Hindu divinity Garuda.

Although the blade of a keris provides its mystical value, it is the hilt that reveals its origins. The difference between a Javanese, Sumatran and Malay Peninsular keris is most apparent in the hilt. The most common form in the southern Thai area of Patani is the keris tajong, a vestigial face with a very long nose; in Java it is the kraton type with an upright figure that no longer bears any resemblance to the Hindu deity it once represented.

The hilt material itself is less indicative of a keris’s origins: wood, metal and ivory are found throughout the region, while more exotic substances, such as rhinoceros horn and hippopotamus teeth, turn up less regularly. Some materials were reserved for the highest levels of society, including gold in many places. Wood, despite its ubiquity in the region, was held in very high regard, for magical properties are ascribed to many types of trees. The kayu hujan panas (“hot rain wood”), for example, might be found at the end of the rainbow; it can only be cut when it is raining and the sun is shining simultaneously.

The keris blade is forged in a manner similar to many other pattern-welded swords of the Islamic world. The first recognizable feature is the shape, which can be anything from straight to having up to 25 “waves” in it. In all cases, the blade flares dramatically toward the hilt. Like the superbly damascened swords found elsewhere in the Islamic world, the keris blade features a variety of patterns (pamor). The most prestigious pamor relates to the Prophet Muhammad; it is a repetition of vertical marks called “Muhammad’s ladder.”

Much has been written about pamor and their significance, but little attention has been given to Islamic calligraphic inscriptions. As with most other art forms, blades had previously featured images of Hindu deities. After the new faith’s acceptance, the word of God was sometimes incorporated to dramatic effect on the blade of the keris and, more often, on larger daggers.

Spears are another neglected feature of the Malay armorer’s art. Any weapon made of steel or high-quality iron was prized in the region, especially in Java, where supplies of iron ore have always been negligible. This esteem continued into the Islamic era. A steel spearhead with the words “Allah” and “Muhammad” in silver inlay must have been a treasured item. With the arrival of the British in the 19th century came regulations for weapons. The spears and keris that have been made since the 20th century are purely ceremonial.

s they did with the adornment of their weapons, the Muslims of Southeast Asia also expressed their faith in the decoration of their homes. Typical of Islamic communities everywhere, their whole way of life was viewed as an expression of devotion. There was an emphasis on nature’s bounty—most obviously wood. It was the closest to primordial clay an artisan could get; all he needed to work it were simple tools.

s they did with the adornment of their weapons, the Muslims of Southeast Asia also expressed their faith in the decoration of their homes. Typical of Islamic communities everywhere, their whole way of life was viewed as an expression of devotion. There was an emphasis on nature’s bounty—most obviously wood. It was the closest to primordial clay an artisan could get; all he needed to work it were simple tools.

Wood abounds in the Malay Archipelago, although previously in larger quantities than in the chainsaw-wielding present. Every sort of building, from an animal enclosure to a mosque, was once made of wood. In pre-Islamic times, the priestly class favored stone. With the arrival of Islam, wood became the supreme building material.

Much of the elite woodwork of the Malay world is a canvas for the application of paint and gilding, often on a spectacular scale. Huge, elaborately carved doorways were created for royal residences, and usually covered with red and gold. These two closely connected colors are manifestations of wealth for the Chinese, a preoccupation that may have influenced their neighbors in the “Southern Sea.” But it is more likely that gold and associated colors are a reference to the sun as the giver of life—symbolized in the Hindu swastika.

The advent of Islam in the region did not diminish the use of gold as a decoration on wood or as an adornment. While Muslim rulers elsewhere avoided wearing gold in excess, their Malay counterparts had no such reticence. A representative of the British East India Company wrote in 1823 about a Sumatran sultan, “He was dressed in a superb suit of gold thread cloth.” The theme was maintained in his jewelry, belt buckle and weapons. Objects made of wood were also likely to have a liberal application of decorative gold, especially where this helped verses from the Qur’an stand out. Many wooden artifacts have strong religious associations. These include boxes for storing the Qur’an and prayer screens that separated male and female Muslims in mosques without solid partitions. Many humbler wooden pieces also exist, including fishermen’s lunchboxes decorated with elaborate patterns.