Written by Piney Kesting

Photographs courtesy of the

John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

|

| CAROL PRATT |

| Headlining the three-week festival’s

opening with Byzantine, Muslim and

Arab songs, children of the Joqat

al-Farah (“Choir of Joy”) filled the

Eisenhower Theater with their voices. |

s the lights dimmed and the

crowd hushed, not a seat was empty in the

Opera House of the John F. Kennedy Center

for the Performing Arts in Washington,

D.C. Honored guests included officials of

the Obama administration, the secretarygeneral

of the Arab

League, ambassadors,

cultural ministers and

diplomats from 22 Arab

nations. As Arab music

began to play, the doors

of the hall opened and

140 children of the

Al-Farah Choir of

Damascus, Syria ran

singing down the aisles.

Dressed in long, colorful robes, they waved

red and green scarves above their heads and

spilled onto the stage to provide an exuberant

opening for “Arabesque: Arts of the

Arab World,” the three-week festival of arts

and culture that brought 800 performers

from all 22 Arab nations to the United

States capital.

s the lights dimmed and the

crowd hushed, not a seat was empty in the

Opera House of the John F. Kennedy Center

for the Performing Arts in Washington,

D.C. Honored guests included officials of

the Obama administration, the secretarygeneral

of the Arab

League, ambassadors,

cultural ministers and

diplomats from 22 Arab

nations. As Arab music

began to play, the doors

of the hall opened and

140 children of the

Al-Farah Choir of

Damascus, Syria ran

singing down the aisles.

Dressed in long, colorful robes, they waved

red and green scarves above their heads and

spilled onto the stage to provide an exuberant

opening for “Arabesque: Arts of the

Arab World,” the three-week festival of arts

and culture that brought 800 performers

from all 22 Arab nations to the United

States capital.

“I found myself tearing up when these

children performed,” confesses James

Zogby, president of the Washington, D.C.-

based Arab American Institute. “I never

expected to see the day when every single Arab country would be represented in

America’s premier institution for the

performing arts.”

“I found myself tearing up when these

children performed,” confesses James

Zogby, president of the Washington, D.C.-

based Arab American Institute. “I never

expected to see the day when every single Arab country would be represented in

America’s premier institution for the

performing arts.”

Oman’s ambassador to the United States,

Hunaina Sultan Al-Mughairy, echoes

Zogby. “I don’t think one can overestimate

the positive impact

of this event,

which celebrates

Arab culture,

being held in the

United States.”

After the

Al-Farah Choir’s

songs, the rest of

the opening-night

program delighted

the audience with a classical performance

by the Qatar Philharmonic Orchestra and

a performance by contemporary Lebanese

composer Marcel Khalifé and his sons.

There was a preview of Debbie Allen’s

“Oman…O Man!” commissioned especially

for “Arabesque,” and the finale came from

the keepers of one of the world’s oldest

musical traditions, the Moroccan Master

Musicians of Jajouka. In all, the February 23

opening was a “mezza”—a sampler—of the

musical cultures that would reverberate

throughout the center until March 15.

|

| CAROL PRATT |

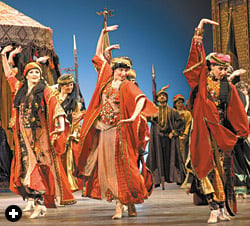

| The Caracalla Dance Theatre, founded in

1968 in Lebanon, blended traditional

costumes, an original score and modern

choreography in “Knights of the Moon.” |

“When people talk about the Middle

East, they tend to think of one ‘Arab culture,’”

comments Nail Al-Jubeir, director of

information and congressional affairs at the

Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia. Admitting

that he himself had never heard of Syria’s

Al-Farah Choir, Al-Jubeir emphasizes that

the festival exposed not only westerners

but also Arabs themselves to this diversity.

“Isn’t it ironic that the performers had to

come to Washington for us to get to know

each other?” he adds, laughing.

The seeds for “Arabesque” were planted

more than four years ago. “I believe the arts

create peace and provide a window onto

understanding people,” says Michael Kaiser,

president of the Kennedy Center. He explains

that since 2004, the Center has sponsored

festivals focused on France, China

and Japan; for 2009, he says, he wanted a

larger festival focused on regions about

which Americans have little cultural

knowledge. “In the Arab world, we know

only about politics and oil,” Kaiser comments.

“We have no knowledge of Arabs as

human beings. I felt it was important for us

to dispel this ignorance, and also to show

the immense beauty that has been created

by Arab people throughout the centuries.”

|

| CAROL PRATT |

| K’Naan (left) grew up in Mogadishu during

the Somali civil war. Grandson of a

renowned Somali poet, he brought

his high-energy hope and protest

to “Arabesque.” |

Kaiser is the first to admit how little he

himself knew about Arab cultures before

the “Arabesque” project. “I knew what I read

in the newspapers,” he explains, adding that

the past four years have taken him and his

small staff on a “remarkable and challenging

journey.”

For the festival’s 21 days, visitors found

an open passport to the Arab world—no

visas required. There were daily performances

on several of the Center’s nine

stages; discussions of Arab literature with

more than 30 authors; Arab films; an exhibition

of 40 wedding dresses from all of the

22 Arab nations; contemporary art exhibits;

shopping in “The Souk” (“Marketplace”)

and learning about the Islamic world’s contributions to science

in the “Exploratorium.”

“Arabesque” is “an

idea that’s been a long

time coming,” says

Alicia Adams, vice president

of the Kennedy

Center’s international

programming and

“Arabesque” curator.

After 9/11, she explains,

the Kennedy Center

kept waiting for the

political situation to

improve. Arguing that

perhaps the best time to act is when things

are at their worst, Kaiser’s first step was

to reach out to the Arab nation ambassadors

in Washington and to the League of

Arab States.

“This has been a long and fruitful relationship,”

comments Dr. Hussein Hassouna,

the League of Arab States’ ambassador to

the US. Ambassadors from Arab countries

gave the project unanimous early support,

he says. Bader bin Saeed, head of the media

|

| Above: Lining up before show time,

some of the 4000 who filled the

Millennium Stage wait to hear the

free concert by hip-hop artist

K’Naan. Below: “Brides of the Arab

World” exhibited more than 40

masterpiece wedding dresses from

all 22 member nations of the

League of Arab States. |

|

| CAROL PRATT(2) |

|

section of the embassy of the United Arab

Emirates, emphasizes that his country

believes that “the best vehicles for crossing

borders are arts and culture.” The festival,

he explains, “represents one of our first

opportunities to display our culture to this

wide an audience in the US.” Jordanian

ambassador Zeid Al-Hussein notes that the

festival “not only showcases samples

of Arab art and culture to Americans, but is

also about emphasizing our humanity and

shared values.”

For its part, the League of Arab States

served as the liaison between Kaiser and the Arab diplomatic community, and

League secretary-general Amre Moussa

signed the sponsoring agreement between

the Kennedy Center and the Arab League.

While Adams wore out her passport

traveling to more than 15 countries as she

scoured the region for artists, performers

and co-sponsors, Kaiser reached out to the

leaders of Arab organizations that, like the

Kennedy Center, promote the arts. In 2007,

the League of Arab States helped arrange a

two-day workshop in Cairo, taught by Kaiser,

for Arab arts

managers. (See sidebar below, “Exporting Expertise, Importing Art”) Some 140 arts

leaders from 17

Arab countries

attended.

During the

workshop,

George Ibrahim,

director of the

Al-Kasaba

Theatre and Cinematheque in the West Bank city of

Ramallah, invited Kaiser to view firsthand

the challenges in promoting arts in

Palestine. Kaiser visited Ramallah twice.

“I have developed a great affection for

Arab culture over these past few years,” he

explains. “I spend a lot of time in Palestine,

and I feel very much at home there.”

|

| MARGOT SCHULMAN |

| French exhibit designer Adrien

Gardère used architectural motifs

associated with the Arab world to frame

exhibits including “Breaking the Veils:

Women Artists From the Islamic

World.” |

|

At “Arabesque,” Al-Kasaba performed

“Alive from Palestine: Stories Under Occupation,”

both times to full houses and standing

ovations. Ibrahim explains that the play

is quietly powerful because each of the five

actors has written a monologue based on

his or her own real-life story. It changes

the way the audience looks at Palestinians,

he says: “We are not ‘news,’ we are human

beings like you.” Ibrahim feels that “Arabesque”

will be a success if people come

not to reinforce stereotypes “but to open

their hearts.”

|

| MARGOT SCHULMAN |

| A 3-D film highlighting

Arab contributions to science played in

the Exploratorium. |

|

For her part, Adams discovered as she

traveled that despite—or at times perhaps

because of—the fraught climate between

Washington and the Arab countries, “everybody

was delighted to have an opportunity

to tell a different story and to put a new

face on the region.” Finding the right mix

between traditional and contemporary

performances and art for the exhibits was

essential. “Generally, I try to focus on the

contemporary, because I think it’s very

important for our audiences to see living,

breathing countries of the 21st century,”

she explains.

Once the performers were selected,

festival coordinator Gilda Almeida and her

two-person staff stepped up to arrange entry

visas, air tickets, ground transport, hotels,

chaperones, translators, identification

badges, insurance, instrument transport,

contracts and security—for all 800 performers.

“People come and buy tickets to the

events and they have no idea how much

work went into this,” she exclaims. “But

that’s the magic!”

Add to that effort the exhibits and the

market: Two tons of cargo shipped in,

including more than 60 delicately handcrafted

wooden mashrabiyyah screens from

Egypt, the 40 wedding dresses and designer

Azza Fahmy’s jewelry collection. “It’s

like pushing a hundred elephants every

day at the same time,” jokes Almeida. “But

when you see the looks on the artists’ faces,

and realize how important it is to them,

somehow you make it happen!”

|

| REGIS VOGT |

| Above: Poet Suheir Hammad

performed “An Evening of

Breaking Poems” as part

of the festival’s literary program.

Below: Egyptian jewelry

designer Azza Fahmy brought

her blend of tradition and

innovation to the exhibit hall. |

|

| MARGOT SCHULMAN |

|

The difficulty with exhibits that involve

22 countries, explains “Arabesque” exhibit

designer Adrien Gardère, is finding “a

common thread that emphasizes the legacy

and the roots that link the artists.” In

the case of the Kennedy Center, which is

neither a museum nor an exhibition hall,

“you want the exhibits to enhance the performing

arts and to capture the attention

of a public that has come primarily for the

performances,” he says. In less than eight

months, Gardère produced exhibits that used Islamic architectural elements and

proved as fascinating and provocative as

the artworks themselves.

Visitors entering the Kennedy Center

were captivated by a row of traditional

wedding dresses in the “Brides of the Arab

World” exhibit. Upstairs, Egyptian sound

engineer Alaa El Kashef ’s “Soundscape:

Souk” evoked a busy Cairo street. Nearby,

the exhibit of Azza Fahmy’s jewelry, a blend

of traditional and modern design, was displayed

nestled in stacks of unglazed clay

pots. Women’s art from throughout the

Middle East appeared in a room constructed

of mashrabiyyah windows—the traditional turned-wood screens that

allow in exterior light while

preserving interior privacy.

In the Exploratorium, visitors

lay back and watched a 3-D film on the golden

age of Islam, projected onto the ceiling.

By the end of the festival’s first week, ticket

sales for “Arabesque” stood 33 percent above the

Kennedy Center’s projections. Every performance

was either sold out or nearly so. The

daily free performances drew overflow crowds

that waited in line sometimes more than an

hour; in particular, Somalian hip-hop artist

K’naan drew a standing-room-only audience

of more than 4000 fans.

Caracalla, Lebanon’s first and most

prominent dance theater, was among those

performing to full houses. Director Ivan

Caracalla called “Arabesque” “a turning point. This is a history-making event

which will open up a new dimension,

both for Arabs and the American public.”

|

| CAROL PRATT |

| Jordan-based fusion ensemble “RUM

– Tareq Al Nasser Musical Group” has

offered up its explorations of Arab and

western sounds to audiences in more

than 40 countries. |

|

Ethnomusicologist Kay Campbell, who

in 1997 co-founded the annual Massachusetts-based Arabic Music Retreat, is more

cautious. She questions whether “Arabesque”

can singlehandedly reinvigorate

an East–West creative fusion that was

beginning to flourish before 9/11. “Miracles

happen in quiet connections that people

make when the spotlight isn’t on,” notes

Campbell. She adds that the numerous

Arab and Arab–American cultural festivals

that began more than 20 years ago (see sidebar below, “Building Bridges”) remain critical to the ongoing

effort in the US to build bridges among

cultures. “The Kennedy Center festival is

important because it serves up the arts of

the Arab world on a silver platter, which,

in a way, gives the culture credibility,” says

Campbell. Her hope is that, with the Kennedy

Center’s imprimatur, the success of

“Arabesque” will encourage other presenters

to bring Arab culture to American

audiences nationwide.

|

| MARGOT SCHULMAN |

| On the opening night of “Arabesque,” Andreas S. Wiser conducted the

Qatar Philharmonic. |

|

David Hamod, president and CEO of the

National US–Arab Chamber of Commerce,

agrees. “‘Arabesque’ represents a beginning,

not an end,” he says. “The next step is to

‘take the show on the road’ to communities

around the United States.

|

| CAROL PRATT |

| From the Comoros Islands off east Africa,

singer/songwriter Nawal blended Indian, Persian and Arab traditions with

east African Bantu polyphonies. She is the first woman musician from the

islands to give performances in public. |

|

If we hope to

improve the image of the Arab world in

the US, it will take a sustained, multi-year

commitment that will reach all walks of

American life.”

Kaiser notes that “Arabesque” is indeed

just the first of many steps. “We will be

bringing Arab culture here forever,” he

affirms. Kaiser explains that large festivals

attract much more attention from both the

public and the press. “We are not just trying to educate those who come: We are also

trying to educate those who don’t. This is

an important part of our strategy,” he notes.

“Twenty years from now, people will

look back at this event and say, ‘I remember

going to that,’” comments Arab American

Institute president Zogby. “Good seeds have

been planted, and they will grow.”

he Kennedy Center probably has one of

the largest arts-education departments

of any performing-arts center in the United

States. We spend $25 million a year on arts

education, out of a $150-million budget,” says

Darrell M. Ayers, vice president of education at

the Kennedy Center. ”Arabesque” has given

quite a boost to the Center’s ability to offer

educators resources about the Arab world.

According to Ayers, teacher workshops

conducted in conjunction with the festival all

sold out. Renowned musician and composer

Simon Shaheen led two sessions that introduced

teachers to Arab music, and Zeina

Seikaly, director of educational outreach at the

Center for Contemporary Studies at Georgetown

University, guided three sessions titled

“Taste of the Arab World,” each focused

on the cuisine of a different country. Ayers

explains that “the objective is for all of these

resources to be used long after the festival

is over.”

he Kennedy Center probably has one of

the largest arts-education departments

of any performing-arts center in the United

States. We spend $25 million a year on arts

education, out of a $150-million budget,” says

Darrell M. Ayers, vice president of education at

the Kennedy Center. ”Arabesque” has given

quite a boost to the Center’s ability to offer

educators resources about the Arab world.

According to Ayers, teacher workshops

conducted in conjunction with the festival all

sold out. Renowned musician and composer

Simon Shaheen led two sessions that introduced

teachers to Arab music, and Zeina

Seikaly, director of educational outreach at the

Center for Contemporary Studies at Georgetown

University, guided three sessions titled

“Taste of the Arab World,” each focused

on the cuisine of a different country. Ayers

explains that “the objective is for all of these

resources to be used long after the festival

is over.”

|

| ILAN MIZRAHI |

| “We can’t be a national leader without

being an international player,” says

Kennedy Center president Michael Kaiser. |

|

The part of the Kennedy Center’s education

department that looks outside the US is the

International Arts Management Program, initiated in 2001 by Kennedy Center president

Michael Kaiser when he stepped up

to the post. “We can’t be a national leader

without being an international player,”

he comments.

One aspect of the international program

is a nine-month fellowship that exposes 10

curators and directors of museums and performing-

arts programs abroad to the methods

of successful US arts organizations. There are

seminars with senior Kennedy Center staff,

three-month practical work rotations at the

Kennedy Center and a weekly strategic

planning seminar with Kaiser.

For Mohammed Abdallah, a program

coordinator at the Mawred Foundation, a

non-profit cultural organization in Cairo, the

fellowship was “an excellent opportunity to

be exposed to the American model of running

arts organizations.” Abdallah spent two work

rotations helping the Kennedy Center with

“Arabesque.”

Last year, the Center launched a subsequent,

four-week international summer

fellowship program with four of that year’s 10 fellows, from Egypt, Kuwait, Lebanon and

Palestine. This year, the summer program will

include eight from Arab League countries.

Kaiser devotes much of his time to teaching

arts leaders in the US and around the world how

to improve their organizations. “If you say

we need to use the arts to learn about other

people, you can’t then add ‘but not the Arab

people,’” says Kaiser. “There is tremendous

value to be gained from Arab and American

arts leaders working together. We hope to be

teaching in the Arab world forever, and we

hope American artists will find a home working

in the Arab world as well.”

n March 13, 500 Girl Scouts from

the Washington, D.C. area were

in the audience for the world premiere of Oman...O Man! Written and choreographed

for “Arabesque” by Emmy Award winner

Debbie Allen, the production features 37

young dancers from Los Angeles, Washington,

D.C. and Oman who discover each

others’ cultures through dance and music.

n March 13, 500 Girl Scouts from

the Washington, D.C. area were

in the audience for the world premiere of Oman...O Man! Written and choreographed

for “Arabesque” by Emmy Award winner

Debbie Allen, the production features 37

young dancers from Los Angeles, Washington,

D.C. and Oman who discover each

others’ cultures through dance and music.

“One of the goals of the Girl Scouts is

to make our girls citizens of a multi-cultural,

international world,” explains Sabrina

McMillan, co-service unit manager for Girl

Scout Unit 42-1. “Leadership training, especially

for this generation, needs to focus on

problems among people.”

|

| RUBY ONG |

| Zoe Sinkford; Ambassador to

the United States from Oman Hunaina

Sultan Al-Mughairy; Madison Harris;

Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center Deputy

Director Mubarak Al-Busaidi; and Angela

Marsh-Coen. |

|

In 2008, McMillan’s troop held a

Muslim–Christian dialogue and invited

80 Muslim Girl Scouts to their Thinking

Day that year. When she learned about

“Arabesque” and the Allen production, she

decided that focusing on Oman for their

2009 Thinking Day festival would be “a

natural follow-up to the 2008 dialogue.”

More than 100 Girl Scouts from 22 local

troops took part in the February 13th

festival. The Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center

in Washington donated frankincense and

bookmarks, and tables displayed the Omani

flag and traditional dress and food, as well

as information on Girl Scouts in Oman.

“It was very rewarding to see firsthand

the girls’ interest in Oman and how it was

expanding their horizons and increasing

their understanding of the world,”

comments Omani ambassador Hunaina

Sultan Al-Mughairy, who visited the festival.

“This event, and attending ‘Arabesque,’

helps prepare the scouts to be international

citizens,” explains McMillan.

thnomusicologist Dr. Ali Jihad Racy

of the University of California at Los

Angeles notes that in the US, one of the

earliest major cultural events to include

performers from the Arab world was the

1893 Chicago World’s Fair, also known as

the World’s Columbian Exposition, which

brought in entertainers from what was then

the Ottoman Empire. Singers, musicians,

belly dancers and actors from Egypt and

Syria filled the Cairo Pavilion, and one of the

favorite midway attractions was the “Street

in Cairo.” This was an eye-opener to the

American public, explains Racy, and it was

one of America’s first exposures to what

was then referred to as “the Orient.”

thnomusicologist Dr. Ali Jihad Racy

of the University of California at Los

Angeles notes that in the US, one of the

earliest major cultural events to include

performers from the Arab world was the

1893 Chicago World’s Fair, also known as

the World’s Columbian Exposition, which

brought in entertainers from what was then

the Ottoman Empire. Singers, musicians,

belly dancers and actors from Egypt and

Syria filled the Cairo Pavilion, and one of the

favorite midway attractions was the “Street

in Cairo.” This was an eye-opener to the

American public, explains Racy, and it was

one of America’s first exposures to what

was then referred to as “the Orient.”

In the Arab world, scholars, musicians,

composers and musicologists from across

the Arab world and Europe gathered in Cairo

in 1932 for the three-week Congrès du Caire.

Convened by Egypt’s King Fuad I, this was

the first cross-cultural conference held in

the Arab world. Fearing the decline of Arab

music, the king had charged the attendees

with its revitalization and preservation. As a

result, some 360 recordings made during the

congress are now in the sound archive of the

Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

Today, the history of these and many

subsequent cross-cultural festivals, both

in the US and in the Arab world, makes a

long and well-established list: The Brooklyn Maqam Arab Music Festival; the Arabic

Music Retreat in western Massachusetts,

now in its 12th year; the Aswat concerts

and Zawaya-sponsored festivals in California;

the ACCESS festivals in Dearborn, Michigan;

Chicago’s Global Fest; the International

Friendship Festival in Long Beach, California;

Jawaahir Dance Company in Minneapolis;

and the Berklee School of Music’s annual

Middle East Festival in Boston, among others.

In April 2005, Yarbous Productions in

Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, organized the

first Arab Festivals Networking Conference.

Nineteen festival directors from 13 Arab

nations were among the 100 participants;

they represented festivals in Bahrain, Byblos,

Madinah, Jerash, Marrakech, Jordan, Cairo,

Mawazin and elsewhere. The conference in

turn established the Arab Musical Festivals

Network, which today promotes intrafestival

cooperation, strengthens Arab–Palestinian

cultural links and promotes emerging Arab

arts and culture.

To this list we can now add “Arabesque”

as a new ambassador of good will and a new

affirmation, as Edward Said said, of “the

power of culture over the culture of power.”

|

Piney Kesting is a Boston-based

free-lance writer and consultant.

Inspired by her first visit to

Lebanon many years ago, she has

been exploring and writing about

the Middle East ever since. Published

internationally, she is a frequent contributor

to Saudi Aramco World. |