|

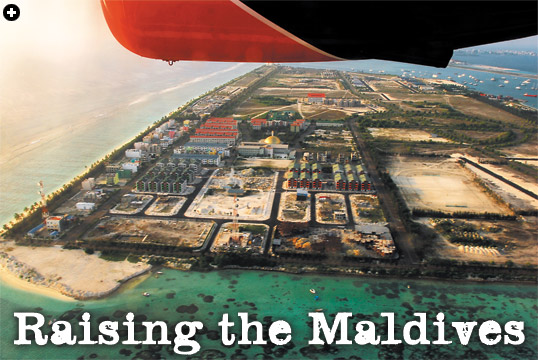

| Roads, homes, businesses and the domed Qatar Mosque now appear at the north end of Hulhumalé, which the Maldivian government hopes will attract some 150,000 people over coming decades. |

Written and photographed by Larry Luxner

|

| Stairway to a diver’s heaven, a resort villa opens to the crystalline Indian Ocean that floats both the Maldives’ tourism economy and the country’s concerns for its future. |

t's another hot afternoon on the artificial island of Hulhumalé, as work crews lay asphalt for a new street and a loud-speaker atop the golden-domed Qatar Mosque calls Muslims to prayer.

t's another hot afternoon on the artificial island of Hulhumalé, as work crews lay asphalt for a new street and a loud-speaker atop the golden-domed Qatar Mosque calls Muslims to prayer.

Inside the nearby Solitaire Café, half a dozen men sit in darkness,

smoking cigarettes, as they wait for the lights to come back on after

a midday power failure.

Despite the annoyance, café owner Abdullah Waseem is clearly

upbeat.

“I love it here,” says the 41-year-old father of two as he dishes out

curried chicken and pours glasses of tea. Born and raised in Addu, at

the southern tip of the 768-kilometer (475-mi) Maldive archipelago,

he has spent most of his life in Malé, the capital city. There, his family

was crammed into a two-room dwelling. Four years ago, he rented a

four-room apartment and became one of the first of what are now

some 5000 permanent residents of Hulhumalé, a box-shaped island

built from landfill just across the sea from overcrowded Malé. “When

we came here, there were very few facilities, no clinics, no police service,

nobody to look after this place,” he says. “People thought it would

take a long time to develop Hulhumalé. But it’s much better now, and

it costs about 40 percent less to live here than in Malé.”

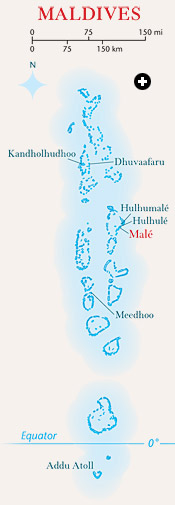

So crowded is Malé, in fact, that roughly 90,000 of the 385,000

people who call the Maldives home are packed into the tiny island’s

2.6 square kilometers (1 sq mi). That makes Malé and its jumble

of high-rises one of the most densely populated capital cities on

Earth—an irony in a country comprised of 1192 islands, the vast

majority of them remote and uninhabited, smack in the middle of

the Indian Ocean.

Ibn Battuta, the famous 14th-century Moroccan traveler, called

the Maldives “one of the wonders of the world” and commented on

the islands’ proximity to each other: “A hundred or so are arranged

in a circle like a ring, with an opening at one point to form a passage....

They are so close together that when leaving one, the tops of the

palm trees on the next are visible.”

|

| A

painted

image

of

the

Maldivian

national

flag

adds

color

to

a

street

in

Malé,

home

to

about

one-third

of

the

Maldives’

385,000

people.

In

November,

elections

brought

a

peaceful

end

to

the

30-year

rule

of

former

President

Maumoon

Abdul

Gayoom. |

Yet man-made Hulhumalé neither looks nor feels anything like

its natural sister islands. From its conception only eight years ago, in

1997, to its official inauguration on May 12, 2004, this work-in-progress

is being meticulously planned to boost the country’s economic fortunes while staving off the rising seas that may one day wipe much of the world’s smallest Muslim nation off the map.

For starters, Hulhumalé is, by Maldivian standards, high ground: It rises two meters (6' 6") above the sea, double the elevation of some 80 percent of the other islands, measured at their highest points. With worldwide sea level rising up to nine-tenths of a centimeter (1/3") per year, the entire country—save Hulhumalé—could be inundated

within a century. And Hulhumalé’s wide boulevards, carefully landscaped gardens and serried ranks of apartment blocks offer a dramatic contrast to the impromptu, colorful hubbub of Malé, only 20 minutes away by ferry.

Hulhumalé was the brainchild of former President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, who late last year stepped down after a 30-year dictatorship.

Under Gayoom, the Maldives became the first country to sign the 1997 Kyoto Protocol urging reductions in greenhouse gas emissions believed by most scientists to cause global warming. It was Gayoom, too, who, after severe flooding in 1987, secured Japanese financing to build a concrete breakwater three meters tall (9' 10") around Malé. And well before “global warming” became

a household term, at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, it was Gayoom who warned that his country might have less than a century before it disappeared underneath the waves.

Until then, say scientists, the likely effects on the Maldives of gradually rising temperatures include increased coastal erosion,

increasing salinity of freshwater sources, altered tidal ranges and patterns and, most significantly, the gradual deterioration,

even destruction, of the coral reefs that comprise both the islands themselves and the natural breakwaters that protect them against the deep ocean just beyond.

“Over half of our islands are eroding at an alarming rate,” Gayoom told delegates in 2007 at the United Nations climate change meeting in Bali. Already, “in some cases, island communities

have had to be relocated to safer islands. Without immediate action, the long-term habitation of our tiny islands is in serious doubt.”

|

| Graffiti

in

Malé

and, below,

new

construction

in

the

capital. |

|

One such island is Meedhoo, 140 kilometers (87 mi) north of Malé and home to around 2000 people.

Ishaag Ahmed, off duty from his job as a security guard at the health clinic, is lounging on a beach hammock with friends. His brother owns a shop that caters to the European tourists who arrive on day trips. Its name is Ozone.

Like most of his friends, Ahmed, 38, doesn’t seem worried about climate change.

“We have a government, and if the time comes to leave, the government

will decide where to put us,” says the former fishing-boat captain, speaking in Dhivehi, the national language of the Maldives.

A tour guide translates for him. Ahmed insists there’s no way he’d ever go live in Malé, and that in Hulhumalé “there’s nothing special for us.”

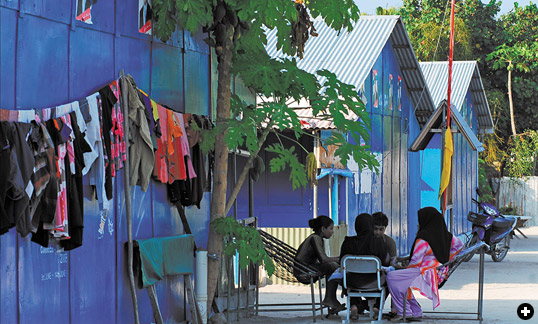

Just a 10-minute walk from Ozone is a makeshift camp housing some 200 refugees from Kandholhudhoo, an island heavily damaged

in the December 2004 tsunami that killed more than 225,000 people in 11 countries, including more than 100 in the Maldives. In what might be a scene from the future, the people in the camp live in houses of wood and corrugated metal sheeting, 12 to 15 to a room. For nearly five years, the government has promised to build houses for them on another island, Dhuvaafaru. In the meantime, the refugees

pass the time playing cards, learning English and kicking a soccer ball around a dusty field.

In Kandholhudhoo, a densely populated island north of Malé, tidal surges, with increasing frequency, flood the homes of those who remain. Some 60 percent of the island’s residents have volunteered

to evacuate over the next 15 years.

Maldivian President Mohamed Nasheed, who took office in November, is aggressively pushing forestation to hold back erosion, the cleanup of coral reefs to slow their deterioration, and the teaching

of environmental protection in all Maldivian schools. In mid-March, he announced that the Maldives has set a goal to become the world’s first carbon-neutral country by 2020. His government is working with international climate experts to plan for wind-and solar-energy production—something he hopes might also attract eco-tourists.

In the meantime, Nasheed has another plan. Soon after his election,

he announced that part of the country’s tourism income will go into a sovereign wealth fund that will be used to acquire land in nearby countries such as India, Sri Lanka or even Australia.

“We can do nothing to stop climate change on our own, and so we have to buy land elsewhere. It’s an insurance policy for the worst possible outcome,” Nasheed told the British newspaper The Guardian.

“We can do nothing to stop climate change on our own, and so we have to buy land elsewhere. It’s an insurance policy for the worst possible outcome,” Nasheed told the British newspaper The Guardian.

That idea doesn’t sit well with Malé cabdriver Ahmed Hussain.

“Nobody wants to go to India or Sri Lanka. They’re much poorer than the Maldives,” says Hussain as he navigates Malé’s narrow, congested streets. “We’d rather go to the Middle East or Europe. But I hope it won’t happen, because we don’t want to be climate refugees.”

Considering the blunt warnings of President Nasheed and his predecessor, it’s surprising Maldivians don’t express more alarm at what might befall their beloved country only a few generations from now.

“It won’t happen. The Maldives will not go under water,” insists Mohammed U. Lantra, general manager of Adaaran Water Resorts, a cluster of pricey, stylish villas on Meedhuparru popular with high-end European, Russian and Japanese tourists. “Yes, the sea level is rising, but at the rate it’s rising, it will take maybe 100 years or more. By that time, none of us will be living.”

Lantra is far more worried about the global economic crisis than global climate change.

He has reason to worry: Last year, the Maldives attracted 500,000 tourists and earned more than a billion dollars from them. But this year, tourism is expected to be down sharply. Lantra points out that the Maldives are “not a cheap destination. In fact, we are considered one of the most expensive resorts in the world.”

Owned by the Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation, Adaaran is the largest foreign hotel company in the Maldives, and its eight resorts employ more than 1000 people.”When tourists want to visit a country,

they’re not interested in knowing what ocean it’s in,” says Lantra. “They want a nice destination where they’ll be safe and get good value for their money.”

|

| A model shows the government s plan for a fully developed Hulhumalé. |

Bob Blake, ambassador from the United States to both Sri Lanka and the Maldives, agrees. “The Maldives has already seen a substantial economic transformation over the last 25 years, thanks largely to the beautiful resorts they have built,” says Blake, who is one of the few ambassadors accredited to the Maldives. The us has given the Maldives both economic assistance and political support

in its transition to an elected presidency. Thanks to tourism development, says Blake, “the Maldives has gone from being South Asia’s poorest country to its richest in just one generation.”

Yet increasing drug abuse andjoblessness is having an effect on the country, not to mention the global economic crisis, which has already put a dent in tourism: The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation’s 16th summit, which was supposed to take place in Malé this October, has been delayed until 2010.

|

| In Meedhoo, refugees from the 2004 tsunami reside in makeshift homes while awaiting completion of permanent homes on Dhuvaafaru, a previously uninhabited island. |

“There is relatively high youth unemployment,” says Blake. “Despite all the development, the country still has to import almost everything, and relies principally on tourism and fishing for all of its income.”

One island tourists rarely visit is Hulhumalé, though the Lonely Planet travel guide suggests “coming here makes a fascinating contrast

to the chaotic capital—here the planning is so precise and mathematical,

you could be on the film set of ‘Brave New World.’”

Nuha Mohammed Riza is deputy director of the Hulhumalé Development Corp. (HDC), a government entity that’s overseeing the construction of Hulhumalé.

Asked about global warming, she says it’s “not something we think about every day, but we also understand that small, low-lying countries like the Maldives are at risk. We need to have measures in place on how to deal with it.”

Ahmed Karam, who works in public relations for HDC, says beaches are shrinking, little by little. “I used to go to Viligili for picnics

when I was a kid, and the beach was bigger then,” he says, referring

to an island 10 minutes west of Malé by ferry. “Now, the waves come right up to the trees.”

In the meantime, HDC is working to attract investment to Hulhumalé.

“Our main objective was to relieve the congestion problem in Malé, and at the same time develop this island into a commercial and industrial hub,” says Riza. “In Malé, there’s no land available because it has gotten so crowded.”

At present, Hulhumalé measures 1.8 square kilometers (0.69 sq mi), and a causeway connects it to Hulhulé, the “airport island” from which foreign visitors arrive and depart. Built entirely from reclaimed sand and coral dredged from the surrounding lagoon, Hulhumalé is envisioned

to house 50,000 people when the first phase of its construction is completed by 2020. By then, the planners say, the island will boast government offices, an industrial zone, shopping centers, tree-lined boulevards, a marina, a national stadium and some dozen mosques.

|

|

| For young and old throughout the Maldives, the questions of climate change impacts are “not something we think about every day,” says Nuha Mohammed Riza, but “we need to have measures in place to deal with it.” |

A second, more ambitious phase involves reclaiming a further

2.4 square kilometers (0.92 sq mi), more than doubling the size of Hulhumalé and bringing the island’s population to 150,000.

Investment in the project, Riza says, is mostly from the government,

with “a bit” from the private sector. “We have three residential neighborhoods where most of the social housing is focused,” she says. “In addition, we have an industrial area where plots of land are being leased for carpentry workshops, warehousing and small fish-processing

plants. We already have two processing plants operating.”

Cookie-cutter apartment buildings rising to 12 stories are beginning

to dot the island, which already also has a school, a pharmacy, lots of shops and at least two Internet cafés.

“We sell the units to the public at cost. We have already sold close to 400 individual plots of land for development,” she says. “The people who buy the land build their own houses. Land costs $30 per square foot here, compared to $600 per square foot in Malé.”

As a result, snaring an apartment on Hulhumalé can feel like winning

a lottery.

“For every round of social housing development we’ve announced, we see the number of applicants far exceed the available supply,” she says, noting that more than 9000 people applied for the 504 housing units currently under construction.

“It’s really overcrowded on Malé, and people want to have nicer accommodations. Also, I think Hulhumalé will provide better housing, education and health facilities,” she says, adding

that for the last two years she has been commuting by boat every day from Malé.

“I would also want to live here, once it’s more developed,” she admits. “But at the moment, there’s not much entertainment.

There aren’t enough people here.”

Indeed, not all is paradise in this utopia, which clearly lacks the charm and appeal of crowded, colorful Malé.

“In Hulhumalé, we have only one problem: Nobody is responsible

for these islanders,” complains Waseem, the café owner. “On Malé and other islands, there are island chiefs. But

here we have only the HDC. And if somebody gets sick or injured, we don’t even have a hospital.”

Yet when asked about climate change, Waseem cheerfully brushes the question aside.

“I’m not worried,” he says as he waits on a customer. “God will look after us.”

|

Larry Luxner, news editor of The Washington Diplomat and publisher of CubaNews, has reported from nearly 90 countries in his journalistic career. More than 17,000 of his stock news and travel photos appear at www.luxner.com. He can be reached at larry@luxner.com. |