Written by Louis Werner - Portraits illustrated by Jesús Conde Alaya

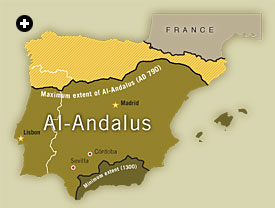

ver since an Arab–Berber army sailed across the Strait of Gibraltar in the year 711 and founded what came to be known as Al-Andalus, Spanish scholars have looked back on the 800 years of Muslim rule that followed and asked questions: How much of the population of Spain converted to Islam?

ver since an Arab–Berber army sailed across the Strait of Gibraltar in the year 711 and founded what came to be known as Al-Andalus, Spanish scholars have looked back on the 800 years of Muslim rule that followed and asked questions: How much of the population of Spain converted to Islam?

How “Hispanized” did the arriving Arabs become? How much did Al-Andalus attach itself to the wider Islamic world (dar al-islam)

and in what ways did it remain part of Spain? To what extent did the land return to Spain culturally— not just politically—after 1492, the year Ferdinand and Isabella forced Muslims

to swear allegiance to the Spanish crown or leave the Iberian Peninsula? And today, how should the Arabic term “Al-Andalus” be used by Spaniards—if at all?

The answers to these questions long defined how Spaniards saw themselves and their place in history. From World War II to 1975, during Generalísimo Francisco Franco’s 38 years of rule, as the rest of Europe moved toward a post-nationalist, common-market future, Spain seemed to be stuck arguing about its past. Its leading intellectuals regarded their country as a bulwark of a purely Christian, anti-Communist Europe. In this environment, the historic case of Al-Andalus was particularly hard to digest, because its 800 years had so clearly marked many aspects of modern Spain.

The answers to these questions long defined how Spaniards saw themselves and their place in history. From World War II to 1975, during Generalísimo Francisco Franco’s 38 years of rule, as the rest of Europe moved toward a post-nationalist, common-market future, Spain seemed to be stuck arguing about its past. Its leading intellectuals regarded their country as a bulwark of a purely Christian, anti-Communist Europe. In this environment, the historic case of Al-Andalus was particularly hard to digest, because its 800 years had so clearly marked many aspects of modern Spain.

Franco’s death in 1975, and the transition to today’s parliamentary monarchy, brought on a revival—some would call it a liberation—of intellectual life. With it, the study of Spanish history entered a new phase as scholars began to rely more on critical readings of historical documents and less on nationalist emotions and ideology.

Manuela Marín is one of the new generation of scholars. She served as chief consultant to the 1992 collection of essays titled The Legacy of Muslim Spain, in which many younger Spanish scholars were published in English for the first time. A professor at the Institute of Philology of the High Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) in Madrid, one of the leading research centers on Al-Andalus, she has mastered the nuances of the Andalucían dialect (which slowly fell out of use after 1492) in order to scrutinize original texts with an eye toward such subjects of present-day interest as gender and cultural assimilation.

A professor at the Institute of Philology of the High Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) in Madrid, one of the leading research centers on Al-Andalus, she has mastered the nuances of the Andalucían dialect (which slowly fell out of use after 1492) in order to scrutinize original texts with an eye toward such subjects of present-day interest as gender and cultural assimilation.

“No doubt about it,” she says. “We have finally moved beyond the complicated meaning of ‘Muslim Spain,’ of discussing whether that period belongs to our own history or to the history of another people.”

Still, the debate echoes today in ways faint and loud. One Spanish graduate student indignantly noted that in his university library’s card catalogue, researchers seeking the subject heading “Al-Andalus” find only the cross-index referral “See ‘Muslim Spain.’”

During the Franco years, it was common for scholars to argue that the Arab period had been a mere interruption of Spain’s historical development, and that, after the completion of the reconquest in 1492, Spain again became a purely European country. Other historians accepted a lingering Arab inheritance—only to blame it for their country’s apparent backwardness compared to its northern European neighbors. It was rare then for any Spaniard to admit Muslims—and, for that matter, Jews—as historical actors on an equal footing with Christians.

|

| bildarchiv preussischer kulturbesitz / art resource |

| Near 1880, Andalucían painter José Moreno Carbonero depicted Boabdil, the last ruler of Al-Andalus, as he turned over the keys to the city of Granada to the Catholic monarchs. |

|

After World War II, one of these rare exceptions was Américo Castro, whose 1948 Spain in History: Christians, Moors, and Jews argued that the country was like a three-stranded rope in which Al-Andalus was an integral and positive influence. On the other hand, in 1956 Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz published a similarly sweeping volume, Spain, an Historical Enigma, that took the contrary, Islamophobic position that the legacy of Arab rule was an alien, harmful influence.

But neither Castro and nor Sánchez-Albornoz could read Arabic historical sources in the original language, and modern scholars now largely dismiss their work as ideological posturing.

Mercedes García-Arenal is Marín’s junior colleague at CSIC and, typical of her generation’s broader experience, has studied and taught abroad. Her special interests are racial and religious assimilation and conversion during the last centuries of the reconquest—subjects that fall under what might be called “frontier studies,” a new rubric that has now bridged the previously compulsory choice between study of either Muslim or Christian Spain.

“Al-Andalus” (ahl-ahn-da-loos) was the name Muslims gave to the southern parts of the Iberian Peninsula that lay under Muslim control between 711 and 1492. The name probably comes from the Arabic name, al-Andaleesh, for the Vandals, a Germanic tribe that inhabited the region from the beginning of the fifth century and went on to control North Africa. (Another Germanic tribe, the Visigoths, followed the Vandals into Spain and partly displaced them.) As the Muslims disputed territory with rival Christian powers to the north, the extent and boundaries of Al-Andalus varied, at times comprising much of the Iberian Peninsula, including southern Portugal. As the Christian reconquista neared victory, Al-Andalus was gradually reduced to isolated principalities, the last of which was the Nasrid emirate of Granada. “Andalucía” (ahn-dah-loo-thi-ah) is the most populous, and second-largest, of the 17 “autonomous communities” that comprise modern Spain. The capital of Andalucía is Sevilla (Seville).

García-Arenal mentions her debt to French historians who opened the study of Al-Andalus to new methods and concepts. She gives particular credit to Pierre Guichard’s 1973 book Al-Andalus: Anthropological Structure of an Islamic Society in the West. “Even the words of the title—‘anthropology,’ ‘Islamic society in the West’—indicate acceptance

of new ways of thinking,” she says.

She notes that the name of her department–“Institute of Philology”–

had a fusty, antiquarian odor to it, and she is pleased that its new name—“Institute of Languages and Cultures”—captures a broader sweep of academic disciplines. “But historians should nonetheless

be vaccinated against infatuations,” she warns. “As long as we stick to critical methods, it shouldn’t much matter if we call our subject area part of Spain or part of dar al-islam.”

Yet the study in Spain of Al-Andalus will probably always be the subject of “infatuations.” Ever since Blas Infante (1885–1936), the father of Andalucían political and cultural autonomy, converted to Islam in 1924 in a bid to reunite what he felt were the two halves— North Africa and Andalucía—of a lost entity, modern romanticizations

of the past have been common.

Archeologists are now comparing the DNA of human remains from the Arab period in Spain with that of contemporary North Africans in an attempt to prove widespread blood ties in addition to their close cultural links. Another recent study has shown a high level of shared DNA between present-day Arabs and Spaniards. María Rosa Menocal, professor of Spanish literature at Yale University,

published The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain (2002) in the wake of 9/11, and despite the fitful nature of the “tolerance” she found, her arguments have been cited by nostalgists seeking evidence

of a “golden age.”

An organization seeking the middle ground in this muddle is Madrid’s Fundación de Cultura Islámica (FUNCI), a public-education group led by Research Director Margarita López, who contributed two essays to The Legacy of Muslim Spain. “I know exactly how dry the study of Al-Andalus seems to a student,” says López, “because I started my studies after completing degrees in law and political science.

Entering that department was like shutting off my air supply. Right off I wanted to break down the walls that kept scholars from talking to each other.”

Recent FUNCI art exhibits and catalogues, all with interdisciplinary

contributions from Spanish scholars, have covered such areas as perfumery, gastronomy, science and gardens. But now López’s challenge is even greater: to steer between what she calls the “cool methods” of academia and such hot topics as North African immigration or the Atocha

train-station bombing

of March 11, 2004.

Recent FUNCI art exhibits and catalogues, all with interdisciplinary

contributions from Spanish scholars, have covered such areas as perfumery, gastronomy, science and gardens. But now López’s challenge is even greater: to steer between what she calls the “cool methods” of academia and such hot topics as North African immigration or the Atocha

train-station bombing

of March 11, 2004.

Rafael Valencia, professor of history at the University of Seville, takes pleasure in pointing a critical spotlight at conventional and sometimes lazy thinking in his field. “I like to say that what happened in the year 711,” he says, “was less an Arab invasion than it was an Islamic revolution in the midst of Visgothic chaos. That turns the subject from chronological history to political history, where there is much more to talk about.

“For us to be called ‘Spanish’ Arabists,” he protests, “is to imply that somehow we are closer in spirit and culture to, say, Danish Arabists, fellow Europeans, than we are to Moroccan Arabists. But Moroccans and I share much more common ground in Al-Andalus than Danes and I would. We merely have to walk through each other’s

old city quarters—Tangier’s medina or Granada’s Albaycín, with their similar urban plans—to get the same idea.”

Valencia cites the name of the Río Guadiana, the river that forms Spain’s southern boundary with Portugal. “A triply redundant toponym!”

he laughs. “Río from Spanish, wadi from Arabic, and ana from ancient Iberian. Who is to say what that so-called ‘border’ is? It’s certainly not a binary function, a matter of either ‘here’ or ‘there.’”

“Our national hero, El Cid, switched sides several times,” he adds. “And Seville’s oldest religious fraternal order for Holy Week celebrations, which considers all other orders to be lesser Catholics, was founded by a man named Mateo Alemán, who had only recently been converted.” Valencia ends with a telling quote from Seville’s greatest poet, Antonio Machado: “El futuro no está escrito; el pasado tampoco”—“The future is not written; neither is the past.”

“Our national hero, El Cid, switched sides several times,” he adds. “And Seville’s oldest religious fraternal order for Holy Week celebrations, which considers all other orders to be lesser Catholics, was founded by a man named Mateo Alemán, who had only recently been converted.” Valencia ends with a telling quote from Seville’s greatest poet, Antonio Machado: “El futuro no está escrito; el pasado tampoco”—“The future is not written; neither is the past.”

In Granada, the Escuela de Estudios Arabes (EEA) looks like what a research institute dedicated to Al-Andalus should look like, housed in a 16th-century Moorish palace with a view of the Alhambra from the patios. But forensic architect Antonio Almagro’s office might fool you, as his computer spins out three-dimensional reconstructions of Seville’s Alcázar Real just as it appeared in the 14th century.

Almagro is on a team of architects and archeologists using ground-penetrating radar, aerial photography, laser measurements and stratigraphic and pottery sequences, as well as comparative analysis of similar construction, to study buildings that have been rebuilt and added to over the centuries as they appeared at a particular time in history.

“Unfortunately,” he says, “as much as we would like help from our philologist colleagues, most Arabic texts on architecture

and buildings are just not that helpful for our needs. We tell them we need facts and figures, meters and angles, not the meters and rhymes that their texts provide.”

Across the EEA’s patio, Luis Molina says he is proud to call himself a philologist, despite the title’s old-fashioned ring. “Emilio García Gómez told me never to consider myself to be a mere translator in the service of historians, because we too were historians of a sort. After all, the history of Al-Andalus begins with language.

Writing Spanish History

The 19th and early 20th centuries were the zenith years for European

“polymath scholars” of Al-Andalus. These included some non-Spaniards like the Dutchman Reinhart Dozy, author of History of the

Muslims in Spain (1861), and the Frenchman Évariste Lévi-Provençal,

author of Arab Civilization in Spain, A General View (1938). Both volumes

are all-in-one summations of an entire civilization requiring a

hubris of encyclopedic learning that is no longer dared today.

The first Spanish Arabist of this era was José Antonio Conde, the very title of whose book, History of the Arab Domination in Spain (1820–1821), reflected his unease with the subject. His followers Julián Ribera, Miguel Asín Palacios and Ramón Menéndez Pidal, more philologists than historians, took a primarily literary interest

in their subjects, seeking the Arab roots of such western canonical texts as The Divine Comedy, The Poem of El Cid and Don Quixote.

The last of this “old school” was

Emilio García Gómez (died 1995), who taught many of today’s younger scholars. Most think there will never be another of his stature, although Professor María Jesús Viguera of Complutense University, at mid-career, has authored almost as many titles in fields ranging from poetry to law to history as García Gómez did in his entire life.

|

| torres molina / corbis |

| Fascist supporters of General Francisco Franco march in Granada in 1946. Franco’s death in 1975 ushered in a new era of civil liberties and intellectual freedom. |

“In past decades,” he notes, “we philologists have pushed deeper into the study of history than historians have pushed into our area. But I dislike the flimsiness of concepts like ‘frontier studies.’ A so-called frontier is a place where the same historical and philological processes are simply a bit more complicated—not a special place in and of itself.”

Molina is just as dismissive of some of the old school’s fuzzy concepts—like convivencia, a neologism meaning the “living together” of Christian, Jewish and Muslim cultures in Al-Andalus. “Why talk only of three cultures?” he asks.

“Why not one culture, or even a hundred cultures? Depending on what kind of culture we are referring to specifically, the number might be more or less than three, in order to be more precise.” Yet here he thinks that Serafín Fanjul, the leading critic of Al-Andalus mythmaking, himself errs. Says Molina: “No reputable scholar

repeats the popular clichés

that Fanjul so fiercely attacks.”

Fanjul, a catedrático (distinguished

professor) at the Autonomous University of Madrid, is in fact less critical of scholars than of popularizers

of the “idea of Al-Andalus,” whom he sees as making similar

simplifications as those who formerly advocated the

“idea of Spain.” Fanjul finds little of an Andalusí legacy left in

southern Spain today: not in its music, not in its food and not

in most of its population.

“I think some advocates for Al-Andalus are intellectually dishonest,” Fanjul says, “because they dress their political claims in academic clothes, arguing that yesterday’s Al-Andalus is the same as today’s Andalucía.” Though his complaint is academic, it has been taken up by less disinterested parties, including politicians opposed to North African immigration and the forging of closer ties with Arab countries. That has put him in the midst of a growing polemic.

Francisco Vidal is a young scholar of Islamic law at the University of Jaén. He received his doctorate the same year his university was given full status within the newly  decentralized system of higher education in Spain. His career thus stands as a counter weight in what had long been considered the “privileged field” of Arab studies, formerly conducted in only a handful of universities by the protégés of eminent professors.

decentralized system of higher education in Spain. His career thus stands as a counter weight in what had long been considered the “privileged field” of Arab studies, formerly conducted in only a handful of universities by the protégés of eminent professors.

Vidal’s specialty is legal opinions, especially the 6500 fatwahs compiled by the 15th-century Moroccan jurist Ahmad ibn Yahya Wansharisi. To him these opinions express a unity of thought in western Islam and a sharp difference from legal thinking of the same time period in, say, Cairo or Damascus. His findings establish a new typology for legal theory in Al-Andalus, showing it as more closely related to North Africa and making it less a special case of “Islam in Europe.”

“Few scholars still obsess about our identity in the study of Al-Andalus,” Vidal says. “We no longer make claims of identity, in either direction, which in the past we almost always did. But our field will always follow an orthodoxy of one type or another. For instance, now we look more favorably at the Almohad period. Earlier Arabists thought they [the conservative Muslim Berber Almohads] came to Spain as destroyers, not as builders, but now we are crazy in love with Almohad architecture and urbanism—we look for it everywhere, and we say, ‘Imagine these people from the desert who fell so quickly in love with city living!”’

Eduardo Manzano, in the department of medieval history in Madrid’s CSIC Institute of Philology, has an interesting perspective on how the field of Arab studies has evolved, partly due to his academic seat outside it. “Much less is known about medieval Christian Spain than about medieval Muslim Spain,” he says, “because Arabists have been quicker to adopt interdisciplinary tools. The government required salvage archeology to be conducted at construction sites during the 1980’s and 1990’s building boom, and Arabists were nimbler than medievalists in making use of these findings.”

Manzano, like most historians today, takes a micro rather than a macro view, one that seeks to tease generalities out of local phenomena. He cites the case of the muwalladun, descendants of some Visigothic converts to Islam who for two centuries remained publically identified

as such, refraining from creating the false Arab genealogies that many other converts did. Then, after those two centuries, they suddenly disappeared from the record. “We have many such ‘delayed fuse’ effects during the Arab conquest and the Christian reconquest,” he says. “That is of interest to me: Why the delay in their full assimilation?

Manzano, like most historians today, takes a micro rather than a macro view, one that seeks to tease generalities out of local phenomena. He cites the case of the muwalladun, descendants of some Visigothic converts to Islam who for two centuries remained publically identified

as such, refraining from creating the false Arab genealogies that many other converts did. Then, after those two centuries, they suddenly disappeared from the record. “We have many such ‘delayed fuse’ effects during the Arab conquest and the Christian reconquest,” he says. “That is of interest to me: Why the delay in their full assimilation?

“I’ve always tried to normalize the study of Al-Andalus,” he says, “to reduce the emotional content of what the old texts tell us. But after the Atocha train bombings, we should make even more effort to steer clear of history, if what we really want is to debate politics. History is not an arsenal with fixed gun positions. It is about change, about when and why things became different from before.”

Manzano is dismayed that Matamoros puppet plays, the popular entertainments stemming from the reconquest that symbolically pit Muslims against Christians, are still taught today, as they have been for centuries, in Spanish schools where most students are Spaniards.

|

| esteban cobo / corbis |

| In 2007, the Spanish government banned all public references to Franco, resulting in the removal of statues such as this one in Santander. |

|

In schools with mostly immigrant children, however, the hero is not El Cid but “Al-Mansour”—a Muslim—and El Cid is the villain. Thus different national histories are being taught to different nationalities, all in the same country. “We should realize that history doesn’t give credibility to people, but rather people give credibility to their own past,” Manzano says.

Such is the intellectual journey that Spanish scholars of Al-Andalus have been making in the last two hundred years, away from the idea that history must argue for or against a particular definition of Spanishness and toward the ideal that Spaniards of all backgrounds should view their past in light of modern historical methods, not through the dusty lens of yesterday’s polemics. In a country where fact-based history prevails, a library card that includes “Muslim Spain” but not “Al-Andalus” might be seen simply as a cataloguer’s lapse, not as a cause célèbre.

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com) is a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World and also writes for El Legado Andalusí and for Américas, the OAS magazine. |

|

Jesús Conde Alaya (lolablanca@hotmail.com) is an artist

living in Granada. |